Читать книгу Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters - Shosh Nagamine - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

BUSHI MATSUMURA SOKON OKINA:

SHURI’S BUJIN

A MASTER OF JIGEN-RYU KENJUTSU

Bushi Matsumura Sokon was born in 1809 in Shuri’s Yamakawa village. Known to the Chinese as Wu Chengda, he wrote under the pen names of Unyuu and Bucho. Who first taught Matsumura te remains the subject of some curiosity. However, it is certain that he was interested in martial arts since childhood. From a good family, by the age of seventeen or eighteen years Matsumura had already displayed the characteristics of a promising bujin. Strong, intelligent, and courteous, Matsumura learned from an early age the importance of bun bu ryo dō (balancing physical training with metaphysical study). In addition to his relentless pursuit of the combative disciplines, he deeply embraced Confucianism, and also became known as a brilliant calligrapher.

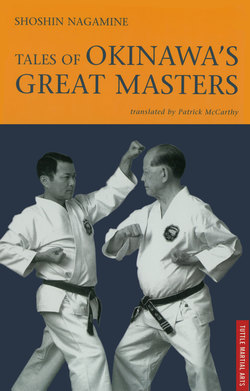

Portrait of Bushi Matsumura.

Having gained such a prominent reputation, Matsumura Sokon had no problem securing an occupation befitting his skills. With proper recommendations, by the age of thirty Matsumura had secured a position in the great palace of Shuri. He remained employed there until his death, serving no less than three kings: Shoko, Shoiku, and Shotai.

Bushi Matsumura was twice sent to Fuzhou and Satsuma as an envoy of the Ryukyu Kingdom. He made his last journey to Fuzhou in 1860 when he was fifty-one years old. Not only was Matsumura physically talented, he was also a man of honor respected in both Okinawa and Fuzhou. During Matsumura’s generation, unlike today, great emphasis was placed on balancing physical and mental learning. Fuzhou was regarded as “the place” where such things were correctly learned. It was considered quite an achievement for a foreigner to be recognized in Fuzhou.

During Matsumura’s generation, the practice of the combative disciplines, in both Fuzhou and Okinawa, took place under an ironclad ritual of secrecy. It wasn’t as if people were unaware of what was going on. Rather, the location in which martial traditions were imparted has customarily been associated with an austere sanctuary of sorts. However, an exception to the martial arts “closed-door” policy of Fuzhou was always made for a man like Matsumura Sokon. He was a man of dignity, and a man who vigorously explored the value of different schools of Chinese boxing. In addition to learning te in Okinawa, and chuan fa (kempo) in Fuzhou, Matsumura Sokon also mastered the principles of Jigen-ryu kenjutsu while stationed in Satsuma (the old name for Kagoshima in Kyushu).

I remember that it was around August of 1942 when I was researching Matsumura’s family lineage that I came across a fifth-generation descendent in the Sogenji district of Naha. There, in an area nicknamed Shimaguaa, I had an opportunity to observe a rusty old Kannon (the Buddhist goddess of mercy) statue about fifteen centimeters in length, a Jigen-ryu makimono, and a shikishi (inscription card), which had been handed down in the Matsumura family. The makimono was so badly rotted that most of its message was unintelligible. However, I still remember one phrase clearly. It read: When holding a sword one should be in the same mood as holding a fishing pole.”

The shikishi, obviously written by a scholarly brush, read: “Matsumura Peichin dono, Omokageo Miruni Nagorino Masurunari, Kimiwa kikokuo nasuto omoeba Ishuin Yashichiro” (To Matsumura Peichin, I am extremely saddened knowing that you will soon depart, [signed] Ishuin Yashichiro). It is obvious that Ishuin was saddened by his friend’s return to Okinawa. Like my other research, I too had copied this valuable document but, like all my other belongings, it was destroyed in the holocaust of October 10, 1944.

As mentioned earlier, it may serve the reader to know that the entire populated areas of greater Naha, including Shuri and Tomari, were completely annihilated by the horrifying air and naval pounding they took during the assault on Okinawa in WW II. Anything not destroyed by direct strikes, was incinerated by the perpetual fires which ensued. Countless thousands of lives were lost in the holocaust, national treasures were destroyed, ancient landmarks obliterated, important cultural property vaporized, and records of every sort simply vanished.

The rusty old statue of Kannon was a symbol of Matsumura’s spiritual conviction and had been handed down in his family for five generations. There was an interesting story about Matsumura and this icon which has outlasted them both. On his return voyage to Ryukyu from Fuzhou, the ship, as was often the case sailing the waters of the East China Sea, encountered a fierce typhoon. The storm became so relentless that both passengers and crew got really scared. After a day and a night the unending tempest forced some to even cry out in fear for their lives. Only one man throughout the entire ordeal remained perfectly calm: Matsumura Sokon. While the frightened onlookers placed their fate in the hands of heaven, Matsumura trusted the goddess of mercy, and quietly chanted a sutra while holding his statue of Kannon.

The violent seas had blown the tiny vessel hundreds of miles north off its course, and, when the storm died down two days later, the ship had drifted to Satsuma. Accommodated by the Satsuma Ryukyukan (Okinawa’s foreign outpost), passengers and crew were able to recuperate and recount the paralyzing experience at the hands of Mother Nature. Everyone was filled with admiration for Matsumura. None had ever witnessed, or even heard of, such tranquil composure under such perilous conditions. The mind of a real bujin was indeed a powerful thing, and Matsumura Sokon was venerated.

THE PEN AND THE SWORD

After the war I discovered that Kuwae Ryokei, the first son of Kuwae Ryosei, had returned to Okinawa from Taiwan. Having gone to Taiwan before the war, Kuwae Ryosei is regarded as the last prominent disciple of Matsumura Sokon. I had heard that Ryokei possessed a makimono (scroll) in Matsumura’s original handwriting, and now that he was back in Okinawa I was anxious to examine it. Hence, I visited him at his home in Shuri’s Torihori-cho in 1951. In addition to allowing me to study the scroll, Ryokei was kind enough to allow me to document my research photographically. Learning of my genuine regard for karate-do and the moral precepts on which it rests, Kuwae Ryokei encouraged me to write about Matsumura Sokon, and the principles for which he stood.

Matsumura’s makimono is the oldest document in the annals of Okinawan karate-do. Besides its age, Matsumura’s precepts are of immense value. Masterfully brushed in his own hand, this document is a genuine treasure. It is believed that the scroll was written sometime after Matsumura was seventy years old. Upon scrutinizing the scroll in question, the late Okinawan master calligrapher, Jahana Unseki, was deeply impressed, and used the words “dignified” and “magnificent” to describe the strength and composure of Sokons brush strokes. It read:

Matsumura’s makimono

To: My Wise Young Brother Kuwae (Ryosei)

Through resolve and relentless training one will grasp the true essence of the fighting traditions. Hence, please consider my words deeply. No less interesting is the fundamental similarity between the fighting and literary traditions. By examining the literary phenomenon we discover three separate elements: 1) the study of shisho; 2) the study of kunko; and 3) the study of jukyo.

The study of shisho refers to commanding words and communicative skills. The study of kunko refers to a comparative study in the philosophy of ancient documents and teaching a sense of duty through example. Yet, in spite of their uniqueness, they are incapable of finding the Way. Capturing only a shallow understanding of the literary phenomenon, shisho and kunko cannot, therefore, be considered complete studies.

It is in the study of jukyo, or Confucianism, that we can find the Way. In finding the Way we can gain a deeper understanding of things, build strength from weakness and make our feelings more sincere, become virtuous and even administer our own affairs more effectively, and in doing so make our home a more peaceful place—a precept which can also apply to our country or the entire world. This then is a complete study and it is called jukyo.

Scrutinizing the fighting disciplines we also discover three divisions: 1) gakushi no bugei, a psychological game of strategy practiced by scholars and court officials; 2) meimoku no bugei, nominal styles of purely physical form, which aim only at winning (without virtue, participants are known to be argumentative, often harm others or even themselves, and occasionally bring shame to their parents, brothers, and family members); and 3) budo no bugei, the genuine methods which are never practiced without conviction, and through which participants cultivate a serene wisdom which knows not contention or vice. With virtue, participants foster loyalty among family, friends, and country, and a natural decorum encourages a dauntless character.

With the fierceness of a tiger and the swiftness of a bird, an indomitable calmness makes subjugating any adversary effortless. Yet, budo no bugei forbids willful violence, governs the warrior, fortifies people, fosters virtue, appeases the community, and brings about a general sense of harmony and prosperity.

These are called the “Seven Virtues of Bu,” and they have been venerated by the seijin (sagacious person or persons; most probably Chinese Confucianists) in the document titled Godan-sho (an ancient journal describing the ways of China). Hence, the way of bun bu (study of philosophy and the fighting traditions, often described as “the pen and the sword”) have mutual features. A scholar needs not gakushi or meimoku no bugei, only budo no bugei. This is where you will find the Way. This indomitable fortitude will profoundly affect your judgment in recognizing opportunity and reacting accordingly, as the circumstances always dictate the means.

I may appear somewhat unsympathetic, but my conviction lies strongly in the principles of budo no bugei. If you embrace my words as I have divulged to you, leaving no secrets and nothing left hiding in my mind, you will find the Way.

—Matsumura Bucho, May 13th (c. 1882)

Matsumura’s makimono is brief, but imparts an invaluable message to all those who may be unfamiliar with the true essence and aims of karate-do: bun bu ryo dō. This emphasizes bun bu ichi nyo, which considers the physical and philosophical as one. There can be no question that Sokon was the man most responsible for this priceless contribution to karate-do. In fact, by way of Matsumura’s makimono, we can conclude that he was principally responsible for proclaiming that the essence of bu (karate-do) in Okinawa meant cultivating these virtues, values, and principles.

If one thoroughly considers Matsumura’s precepts it becomes evident that his message is the fundamental concept of humanity, and its understanding is crucial to the development of shingitai (lit., spirit, technique, body; referring to the development of an indomitable spirit through the use of physical technique). However, during this generation of materialism in Japan, people seem to be more preoccupied with possessions rather than the pursuit of such a spirit.

Because of this radical shift in direction, modern Japanese education has ignored the spirit of kokoro (shin). Too much emphasis placed on materialism has resulted in a loss of moral values. The Japanese people now face a social crisis. The time has come to learn in sincere humility the true meaning of “karate ni sente nashi” (there is no first attack in karate). Hence, I would like to introduce two poems which were handed down in Okinawa long ago.

Poem:

Chiyuni kurusatteya ninrarishiga, chiyukuruche ninraran

Interpretation:

In spite of being troubled by other people, one can still sleep. However, if one troubles other people, a guilty conscience makes it difficult to ever sleep soundly.

Poem:

Ijinu ijiraa tei hiki, teino dejiraa iji hiki

Interpretation:

Standing up for what one believes in

requires the balance of breath and force.

(too much of either is unwelcome)

These precepts were once closely associated with what has been historically described as the “Okinawan spirit.” I believe that these abstracts are excellent lessons for today’s karateka. Pondering the depth of their message one can recognize how self-control, the secret of karate-do, is the principal element in understanding that budo is not for fighting.

In martial arts, wherever kokoro has been forgotten, or never learned, so too will the principle of karate ni sente nashi also be misunderstood, or worse, not even known! In reality, karate ni sente nashi is a warning, and any martial artist who ignores this maxim is a hypocrite. There are teachers who erroneously believe that this ancient proverb simply means responding to a challenge. I say they are wrong and that responding to any challenge only condones violence. The karate ni sente nashi maxim is based on a poem by a famous Zen prelate named Muso Soseki (1275—1351), founder of Kyoto’s Tenryu temple.

One day during a boat voyage, the priest Muso was attacked by a thug who split his head open with an oar. Caught off-guard, the deshi (disciple) of Muso immediately lunged to fight in retaliation. However, Muso restrained his deshi and chanted these words:

Poem:

Utsu hitomo utaruru hitomo morotomoni,

tada hitohikino yumeno tawamure.

Interpretation:

The attacker and the defender are both nothing more

than part of an incident in an illusion which exists

but for only a moment in the span of one’s life.

After pondering the brilliant utterance of the Zen prelate, I came to understand that rather than “not responding to the challenge,” karate ni sente nashi really means tatakawa zushite katsu: victory without contention, or winning without fighting.

Another poem which compels one to consider the magnitude of kokoro, is the following abstract composed by a noted doctor of philosophy, Nishida Ikutaro.

Poem:

Waga kokoro fukaki fuchiari yorokobimo,

urehino nanimo todokajito omou.

Interpretation:

My kokoro exists in an abyss so deep, it is a place which

even the waves of joy or fear cannot disturb.

From the perspective of the martial arts, it is impossible to know the kokoro (spirit) of “victory without contention” if one has not yet transcended the illusion of victory or defeat: the physical boundaries of gi (technique) and tai (body).

People often concluded that the 5th-century B.C. Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu advocated the sente precept. Actually, we can see in his later works a proverb which more clearly illustrates his genuine intention. It suggests: “The essence of kokoro must surface from attraction rather than promotion if it is ever to be clearly understood. Only at that time will one’s kokoro allow enough pliability to yield in the winds of adversity; the circumstances dictate the means. This is, so to speak, the secret of victory without contention, and it must be acknowledged.” I will directly address the karate ni sente nashi maxim later in this book, but I would like to first return to Bushi Matsumura’s story.

During his later years, Matsumura Sokon taught karate to many students at the ochayagoten (tea garden) in Shuri’s Sakiyama district. The ochayagoten (pronounced uchayaudon in Okinawan) was also known as tooen, or east garden. During the Ryukyu Kingdom, Okinawan families of position learned chado (tea ceremony), kyudo (Zen archery), and budo (martial ways) in this tranquil sanctuary.

Located just next to the great castle of Shuri, the ochayagoten was often used by the royal (Sho) family. Unfortunately, it too was destroyed during the war. All that now remains of the ochayagoten is an empty field. However, the memories of Matsumura and those students who learned martial arts from him in that garden sanctuary live on.

The principal students of Bushi Matsumura Sokon who regularly learned from him at the ochayagoten were: Itosu Anko (1832—1916), Kuwae Ryosei (1858—1939), Yabu Kentsu (1866—1937), Funakoshi Gichin (1868—1957), Hanashiro Chomo (1869—1945), Kyan Chotoku (1870—1945), Azato Chikudon Peichin (1827—1906), Kiyuna Chikudon Peichin (1845—1920), and Sakiyama Chikudon Peichin (1833-1918).

YIELDING TO THE WINDS OF ADVERSITY

I would now like to introduce you to a rather unusual, but nonetheless stirring episode in the life of Bushi Matsumura. After king Shoko-O retired, he was called Boji-Ushu and lived in comfort at his villa in Kowan (present day Urazoe). There was a wild bull kept by a family in his neighborhood which, on occasion, would break free and trample the valuable crops in the village field. When such a thing happened people often got injured before the beast could be recaptured. This caused a lot of trouble and the villagers were very anxious about the situation. However, after Boji learned of the problem he secretly devised a plan to deal with the menace. Believing that Matsumura was a great bujin who could easily defeat the beast, Boji commanded that he be pitted against the bull. Considered a competent ruler, the retired king knew little about such trivial matters, and actually placed Matsumura in considerable danger by ordering such a contest.

When Shuri officials got wind of the outlandish proposal they were embarrassed. However, in spite of how ridiculous the request was, Matsumura showed no concern and simply said “How can I refuse the former king?” His only request was that he might be permitted a few days to prepare for the contest. Boji agreed and remarked, “Take as much time as you like, as long as I can see you fight the bull firsthand.”

On the day of the gladiatorial-style match, people from all over packed the neighborhood. When the moment came to face the ferocious beast, Matsumura entered the arena and calmly advanced towards the bull clutching only a short wooden club in his hand. Irritated by the crowd, the bull bucked violently, snorted, and scratched the ground as it prepared to engage its adversary. When the bull charged out into the center of the arena and faced Matsumura, much to everyone’s astonishment, it let out a fervent cry and ran off.

Dumbfounded, everyone including the king stood holding their breath in disbelief, until finally the king shouted: “Well done, Matsumura. You are indeed the most remarkable bushi in all of the world!” What the king, and the townspeople did not know was the reason why, on seeing Matsumura, the bull ran away. During the time that Matsumura was supposed to be preparing for the bout, he was actually conditioning the bull.

Under the cover of darkness, Matsumura secretly went to the animal’s pen where, every night for a week, with a konbo (small wooden club) and dressed in the same outfit, he screamed and vigorously beat the head of the bull until even the sight or sound of Matsumura caused the beast to shudder in fear. Naturally, in the arena, when the beast got close enough to smell, hear, and see that it was Matsumura with the konbo, it ran off.

Following that remarkable incident the young subordinate became known throughout the kingdom as “Bushi” Matsumura, the fearless warrior. This episode really characterizes Matsumura’s exceptional personality. Unlike other powerful but reckless bujin, Matsumura realized that a contest of strength between man and beast was meaningless, but used his wit to prove a point. It is no wonder the fighting tradition he cultivated became so popular; with such a reputation, everyone wanted to be like Bushi Matsumura.

Despite diligently searching for Matsumura’s actual dates of birth and death, I was unable to locate them. The documents I once had were so badly burned from the air raid they were of no use. However, I was able to establish what his date of birth was by conducting the following analysis: I located Uto Kaiyo, who was a very close relative of Matsumura’s. She was born May 30, 1896, and lived in Shuri. Kaiyo’s mother always told her that in the same year that she was born her family all attended Matsumura’s beiju (eighty-eighth birthday) celebration. Hence, we can be sure that Matsumura Sokon was eighty-eight years old in 1896. Based on the testimony of Uto Kaiyo, it would therefore be safe to conclude that the famous bushi was born in 1809.