Читать книгу Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters - Shosh Nagamine - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

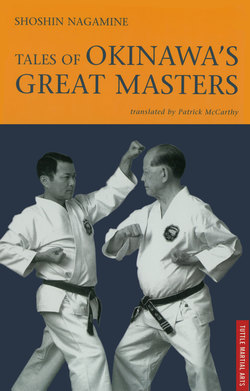

I wonder if it was 1940 or 1941 that I first noticed that remarkable photograph in the display corner of Matayoshi’s Photo Studio on Uenokura Street in Naha. It was a photograph portraying two men standing together, bare-chested. Their musculature was very impressive. One man wore a topknot, and at a glance I could tell he was a sumo wrestler. By comparison, the other man was very short and narrow-shouldered. However, his deeply trained muscles and bone structure were not inferior to that of the six-foot sumo wrestler.

At that time I had come home to Okinawa for winter vacation, but I remember returning to Tokyo with an impression of that picture still fresh in my mind. Fortunately I had a friend, a sturdy shodan (1st degree black belt) in judo, who also practiced karate, from whom I found out more about that impressive photograph.

The sumo wrestler was named Satonishiki and the other man was Mr. Nagamine Shoshin, a local master of karate. My friend explained that Nagamine Sensei was a policeman and one of the most prominent martial artists in Okinawa. Although this was my first time to hear the name of Nagamine Shoshin I already knew of his physique from the photo at Matayoshi’s studio. I also learned that the sumo wrestler Satonishiki was ranked in the top ten by the monthly magazine Baseball World. At that time, headline articles and pictorials of sumo wrestlers were featured in this popular magazine, issued by Baseball Magazine Company.

The physical contrast between Nagamine Shoshin and Satonishiki was obvious from that photo. However, being neither an expert of physical education nor familiar with karate or sumo, I was uncertain who was the stronger of the two. Admiring that photograph at the Matayoshi Photo studio, I still remember to this day how impressed I was by it.

The eminent Funakoshi Gichin came from the head of my family. He was the cousin of my father. Gichins father’s name was Gishu, and my grandfather, Gifu, was his brother. Actually, Funakoshi Gichin was old enough to be the parent of my father. Funakoshi Gichins second son, Giyu, was the same age as my father. In my youth I was influenced by uncle Giyu, and often visited Gichin’s house. At that time he had his new dojo at the Kishimojin area in Zoshigaya, Tokyo.

Called the Shotokan, I often visited Funakoshi’s dojo on Sundays as a messenger of uncle Giyu. Uncle Gigo, the third son of Funakoshi Gichin, taught there at that time. Uncle Gigo commanded me to practice in the dojo, but Gichin Sensei said I was not suited to practice karate. That didn’t mean that I was not interested in karate, it just meant that I didn’t practice it. However, I continued going to the dojo regularly. I wanted to be strong like other boys, but the notion of training my mind and spirit through the discipline of martial arts just did not capture me at that time. However, I now regret that I could not find the courage to enter Gichin Sensei’s world, even though I was so close to him.

It was Nagamine Ichiro (no relation) who first gave me the chance to feel close to Nagamine Shoshin Sensei. Nagamine Ichiro had asthma as a child. However, after he studied karate under Nagamine Sensei, his health improved. After the war, Nagamine Ichiro recommended that I also consider practicing karate because of my asthma problem. At that time, both Ichiro and I worked for the Okinawan Peoples’ Government (forerunner of the Ryukyu government). Ichiro had overcome his asthma problem through karate training. This interested me, but I couldn’t decided whether or not to begin training because I was so lazy.

Even though I had heard the name of Nagamine Shoshin often since 1940 or 1941, it was not until I moved back to Naha in 1950 that I was finally able to meet him. I can’t remember just how I became so close to Nagamine Sensei, but I did.

These days I don’t see Nagamine Sensei very often, but when I do, I feel as if it was just yesterday that we last met. That’s how close we are. Yet, not being a budoka, I can’t imagine that I am a very good companion for the master, never speaking about the discipline. Nonetheless, the story of Master Nagamines enlightenment through bu is a great lesson for us all. Master Nagamine is a great inspiration, not only for karateka, but also for people like myself, who remain outside of the discipline.

In this book, Master Nagamine presents the combat legacy of our people: the legend of Okinawa’s bushi (warriors). Included in his presentation are Matsumura of Shuri, Matsumora of Tomari, Motobu Saru, and Kyan Chotoku, among others, all famous bujin (martial artists). After I read the manuscript once, I felt that this was the first book about karate that was both illuminating and easy to understand.

I was impressed that Nagamine Sensei did not introduce karate in a mysterious way, as if it was an obscure or “all-mighty” phenomenon. Rather, the art has been presented by a person who knows karate very well, a person who truly understands the real meaning of the discipline and its authentic waza (technique). Mysterious stories about karate sometimes confuse the actual purpose of the art. I can understand and accept the reason behind them, as they serve to spark interest in young boys. However, each reader or listener should interpret the message in his own way.

Stories about courageous warriors have always provided young boys with dreams about becoming strong and moral. Since karate-do is native to our island, it provides a sense of patriotism and regard for one’s heritage and community. I too, remember as an elementary student reading a story which left a remarkable impression on me. So too, I believe, will Nagamine Shoshin’s impressive publication greatly influence the young people of this generation.

Even though I know little about karate-do, I still maintain a great passion for this remarkable tradition. Every time I have observed a demonstration of the art by young people, I have been moved. When I see the frightening beauty of karate’s magnificent ferocity I experience an inner exhilaration. Strange as it may seem, I secretly shed a tear of regret for the great opportunity I had let pass.

Nearly a half-century has passed since I first saw the photograph of Nagamine Sensei and Satonishiki. Yet, still full of life, it is as if Nagamine just stepped out of the photograph yesterday. Having contributed so much to the growth and development of karate-do in Okinawa and throughout the world, we are all deeply grateful for Nagamine Sensei’s outstanding efforts, and this book is a testament to his dedication.

—Funakoshi Gisho