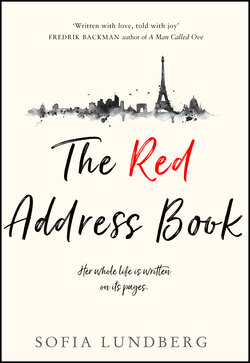

Читать книгу The Red Address Book - Sofia Lundberg - Страница 12

The Red Address Book

ОглавлениеN. NILSSON, GÖSTA

I was used to people occasionally falling asleep after having too much to drink. It was my job to wake them and send them on their way. But this man wasn’t asleep. He was staring straight ahead. The tears ran slowly down his cheeks, one by one, as his eyes focused on an armchair where another man — young, with a halo of golden-brown curls — was sleeping. The young man’s white shirt was unbuttoned, revealing a yellowed undershirt. On the tan skin of his chest, I could see a tattoo of an anchor, unsteady lines in greenish-black ink.

The man noticed me.

“You’re upset, sorry, I …” I hurried to leave.

The man turned his head, lowering his shoulder to the leather armrest so that he was now half-lying across the chair.

“Love is impossible,” he slurred, nodding towards the armchair he was staring at.

I tried to make my voice sound firm. “You’re drunk. Please, sir, get up; you need to leave before Madame wakes.” His hand gripped mine as I struggled to pull him to his feet.

“Don’t you see, miss?”

“Don’t I see what?”

“That I’m suffering!”

“Yes, I can see that. Go home and sleep it off, and your suffering will feel a little lighter.”

“Just let me sit here and look at this perfection. Let me enjoy this perilous electricity.”

He tangled his words as he attempted to capture his mood. I shook my head.

It was my first meeting with this delicate man, but it certainly wouldn’t be the last. Often, as the apartment emptied and the new day dawned over the rooftops of Södermalm, he lingered, lost in thought. His name was Gösta. Gösta Nilsson. He lived further down the street, at Bastugatan 25.

“One can think so clearly at night, young Doris,” he would say whenever I asked him to leave. Then, with drooping shoulders and a bowed head, he would stagger off into the night. His cap was never straight, and the tattered old jacket he wore was too big; it hung slightly lower on one side, as though his back was crooked. He was handsome. Often tan, his face had classical features — a straight nose and thin lips. There was plenty of goodness in his eyes, but he was usually sad. His spark had gone out.

Only after several months did I realise that he was the artist whom Madame worshipped. His paintings hung in her bedroom, huge canvases featuring brightly coloured squares and triangles. No theme to speak of, just explosions of colour and shape. Almost as if a child had been let loose with a brush. I didn’t like them. Not at all. But Madame bought and bought. Because Sweden’s Prince Eugen did the same. And because surrealist modernity had a particular power that most people couldn’t understand. She appreciated the fact that Gösta, like her, was an outsider.

It was Madame who taught me that people come in many different shapes. That others’ expectations of us are not always right. That there are many routes to choose from on the journey we are all making towards death. That we might find ourselves at difficult junctions, yet the road may still straighten. And that the curves aren’t dangerous.

Gösta always asked a lot of questions.

“Do you prefer red or blue?”

“To which country would you travel if you could go anywhere at all on earth?”

“How many one-öre sweets can you buy with one krona?”

After that last question, he always tossed me a krona. He flicked it into the air with his index finger and, with a smile, I caught it.

“Spend it on something sweet, promise me that.”

He could see that I was young. That I was still a child. He never reached to touch my body the way the other men did. He never made comments about my lips or budding breasts. Sometimes he even helped me in secret: picking up glasses and taking them to the corridor between the dining room and kitchen. Whenever Madame noticed, she would slap me afterwards. Her thick gold rings left red marks on my cheeks. I covered them with a pinch of flour.