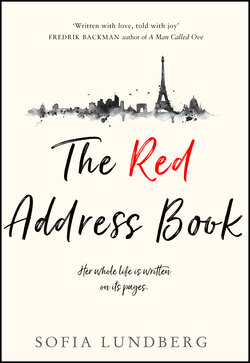

Читать книгу The Red Address Book - Sofia Lundberg - Страница 14

The Red Address Book

ОглавлениеN. NILSSON, GÖSTA

Gösta was a man of many contradictions. At night, and in the early hours of the morning, he was fragile, full of tears and doubts. But in the evenings preceding those moments, he was desperate for attention. He lived off it. Needed to be at the centre of the discussion. Climbed onto the table and broke into song. Laughed more loudly than anyone else. Shouted when political opinions differed. He was happy to talk about unemployment and female suffrage. But most of all, he spoke about art. About the divine in the act of creation. What the fake artists would never understand. I once asked him how he could be so sure he was a genuine artist himself. How did he know it wasn’t the other way around? He pinched me hard in the side and subjected me to a long tirade about cubism and futurism and expressionism. The blank look on my face was like fuel. It ignited his laughter.

“You’ll understand one day, young lady. Form, line, colour. It’s so fantastic that, with their help, you can capture the divine principle behind all life.”

I think that he enjoyed my lack of understanding. That he was relieved when I didn’t take him as seriously as the others did. It was like sharing a secret. We could be walking side by side through the apartment; he would hang back, then jump forward, from time to time, to resume our pace. “Soon I’ll say that the young lady has the greenest eyes and the most wonderful smile that I’ve ever seen,” he would whisper, and my face would always flush, the same shade of red. He wanted to make me happy. In that alien environment, he became my comfort. A replacement for the mother and father I missed so dearly. He always sought my eye when he arrived, as if to check that I was OK. And he asked questions. It’s odd; certain people feel particularly drawn to each other. That was how it was with Gösta and me. After just a few meetings, he felt like a friend, and I always looked forward to his visits. It seemed he could hear what I was thinking.

Occasionally, he would bring company when he came over. It was almost always some young, tan, muscular man, far removed, in both style and demeanour, from the cultural elite who generally frequented Madame’s parties. These young men usually sat quietly in a chair, waiting while Gösta emptied glass after glass of deep red wine. They always listened intently to the conversation, but never joined in.

I saw more than that, once. It was late at night, and I had stepped into Madame’s room to fluff up her pillows before she went to bed. Gösta’s arm was around a young man’s hip. He let go, as though he had burned himself. They were standing close together, face to face, in front of two of Gösta’s paintings, which were propped against the bed. Neither said anything, but Gösta looked me straight in the eye and held a finger to his mouth. I plumped the pillows with one hand and left the room. Gösta’s friend disappeared into the hallway and out the front door. He never came back.

They say that madness and creativity go hand in hand. That the most creative among us are those who stand closest to gloominess, sadness, and obsessional neuroses. At the time, no one thought like that. Back then, feeling unhappy was considered ugly. It wasn’t something people talked about. Everyone had to be happy all of the time. Madame with her impeccable makeup, her smooth hair and glittering jewels. No one heard her anguished weeping at night, once the apartment had fallen silent and she was left alone with her thoughts. She probably threw her parties to keep those thoughts at bay.

Gösta attended for the same reason. Loneliness drove him from his apartment, where his many unsold canvases were stacked against the walls, a constant reminder of his poverty. He was often marked by the sober melancholy I had noticed when we first met. When in that state, he would remain seated until I forced him out. He always wanted to return to his Paris. To the good life he had loved so dearly. To the friends, the art, the inspiration. But he never had the money. Madame provided him with the dose of Frenchness he needed to survive. One short moment at a time.

“I can’t paint anymore,” he sighed one evening.

“Why do you say that?” I never knew how to respond to his gloominess.

“It amounts to nothing. I don’t see pictures anymore. I don’t see life in clear colours. Not like before.”

“I don’t understand any of that.” I forced a smile. Rubbed his shoulder with one hand.

What did I know? A girl of thirteen. Nothing. I knew nothing about the world. Nothing about art. To me, a beautiful painting was one that depicted reality as I understood it. Not by means of distorted, colourful squares forming equally distorted figures. I thought it was probably a stroke of luck that Gösta could no longer produce those terrible paintings that Madame stacked in her wardrobe in order to put food on his table. But later, I would find myself pausing, feather duster in hand, in front of his work. The confusion of colours and brushstrokes occasionally managed to catch my imagination, letting it run wild. I saw something new. With time, I learned to love that feeling.