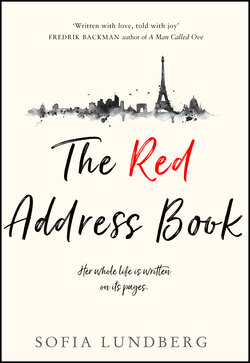

Читать книгу The Red Address Book - Sofia Lundberg - Страница 16

The Red Address Book

ОглавлениеS. SERAFIN, DOMINIQUE

I remember the moon, a thin sliver against a pale-blue backdrop, and the rooftops beneath it, the laundry hanging on the balconies. The smell of coal smoke from the hundreds of chimneys. The train’s rhythmic pounding had become a part of my body over the long journey. Day had just started to dawn as we finally approached Gare du Nord after many long hours and several changes. I got up and leaned out of the third-class window. Breathed in the scent of spring and waved to the street children running barefoot along the tracks, their hands outstretched. Someone tossed them a coin, which halted them abruptly. They flocked around the small piece of treasure and started to fight over who would get to keep it.

I kept a tight hold on my money. I held it in a small, flat leather purse, knotted to the waistband of my skirt with a white ribbon. At regular intervals I reached down to check that it was still there. Ran my hand over the soft corners I could feel beneath the fabric. My mother had slipped the purse into my hand just before I left, and it contained all the money she had been saving, money she used only in special circumstances. Perhaps she loved me after all? I was so angry with her, often thought that I never wanted to see her again. But at the same time, I missed her so unfathomably much. Not a day went by without my thinking about her and Agnes.

That purse was my one source of comfort as I rolled towards my new life. Its weight against my stomach kept me calm. Then the wheels screeched loudly as the brakes were applied. I clasped my hands to my ears, making the man across from me smile. I didn’t smile back, just hurried to leave the train.

A porter was lifting Madame’s luggage onto a black iron trolley. I waited next to that growing mountain, my own bag wedged between my feet. The young porter ran back and forth. His face was glistening with sweat, and when he used his shirtsleeve to wipe his brow, it turned brown with dirt. Bags, trunks, round hatboxes, chairs, and paintings were stacked on top of one another on the soon-overloaded trolley.

People were pushing past us. The long, dirty skirts of the poorer passengers swept by the glossy shoes and neatly pressed trousers of the upper-class men. But the elegant ladies waited on board, in the first-class car. Only when the platform was empty, and the second- and third-class passengers had disappeared, did they slowly, in their high heels, descend the three iron steps.

Madame’s face broke into a smile when she saw me waiting. The first words to leave her mouth weren’t, however, a greeting. She sighed about the long journey and her boring travel companions. About her aching back and the uncomfortable heat. She mixed French and Swedish, and I quickly got lost, though she didn’t seem bothered by my lack of responses. She turned on her heel and started walking towards the station building. The porter and I followed her. He pushed the trolley ahead, using his hip to manage the weight. I grabbed the metal pole at the front and pulled, to help him. I carried my small suitcase in my other hand. My dress was damp with sweat and I caught its musty, sharp odour with every step I took.

The arrivals hall, with its elegant green cast-iron pillars, was full of people moving in every direction across the stone floor. The sound of their footsteps echoed loudly. A small boy in a light-blue shirt and black shorts started following us, waving a pink rose in the air. His lank bangs hung limp over a pair of bright blue eyes, which stared at me, pleading. I shook my head, but he was stubborn, holding out the flower and nodding. His hand begged for money. Behind him was a girl with two thick brown braids. She was selling bread, and her brown dress, much too big for her, was dotted with flour. She held out a piece to me and waved it back and forth, so that I would catch its freshly baked scent. I shook my head again and sped up, but the two children did the same. A man in a suit blew a huge cloud of smoke into the air ahead of me. I coughed loudly, which made Madame laugh.

“Are you shocked, my dear?”

She stopped.

“It’s nothing like Stockholm. Oh, Paris, how I have missed you!” she continued, smiling broadly before launching into a long tirade in French. She turned to the children and said something in a firm voice. They looked at her, the girl curtsied and the boy bowed, and they ran away, footsteps pattering.

Outside the station building, a chauffeur was waiting for us. He held open the back-seat door of a high black car. It was my first-ever car ride. The seats were made of the softest leather, and when I sat down, the scent of it rose, and I breathed it in deeply. It reminded me of my father.

The floor of the car was covered in small Persian rugs; red, black, and white. I made sure to place my feet on either side of them, so as not to get them dirty.

Gösta had told me about the streets, about the music and the smells. The ramshackle buildings of Montmartre. I stared aimlessly out the window and saw the beautifully ornate white façades rushing by. There, in the exclusive neighbourhoods, Madame would have fit in, like all the other elegant ladies. Pretty dresses and expensive jewellery. But that wasn’t where we stopped. She didn’t want to fit in. She wanted to stand out in contrast to her surroundings. To be someone who caused others to react. For her, the unusual was normal. That was why she collected artists, authors, and philosophers.

And it was precisely to Montmartre that she took me. We slowly climbed its steep slopes and eventually pulled up at a small building with peeling plasterwork and a red wooden door. Madame was delighted, her laughter filling the car. As she eagerly waved me in, to the stale, musty rooms, she radiated energy. The few pieces of furniture were covered in sheets, and Madame moved from one room to the next, pulling them back. Revealing colourful fabrics and dark woodwork. The style of the house reminded me strongly of her apartment in Södermalm. Here too were paintings, many paintings, hung in double rows on the walls. A muddle of themes, a variety of styles. A glorious mishmash of modern and classical. And there were books everywhere. In the living room alone, she had three tall bookshelves built into the wall, holding row after row of beautiful leather-bound books. Beside one of them stood a ladder on runners, which made it possible to reach the volumes at the very top.

Once Madame had left the room, I stood by the shelves, scanning the names of famous authors. Jonathan Swift, Rousseau, Goethe, Voltaire, Dostoyevsky, Arthur Conan Doyle. I had only heard people speak of these names; now their books were all here. Full of ideas I had heard of, but not understood. I took a volume from the shelf, only to discover it was in French. They were all in French. Exhausted, I slumped into an armchair and mumbled the few words I knew. Bonjour, au revoir, pardon, oui. I was tired from the journey and everything I had seen. I couldn’t keep my eyes open.

When I woke, I found that Madame had draped a crocheted blanket over me. I pulled it tight around my body. The wind was blowing in through one of the windows, and I got up to close it. Then I sat down to write a letter to Gösta, something I had promised myself I would do as soon as I arrived. I gathered all my first impressions and jotted them down as well as I could, with the meagre language of a thirteen-year-old. The sound of the train platform beneath my feet as I crossed it, the smells surrounding me, the two children with the bread and the flower, the street musicians I heard from the car, Montmartre. Everything.

I knew he would want to hear it all.