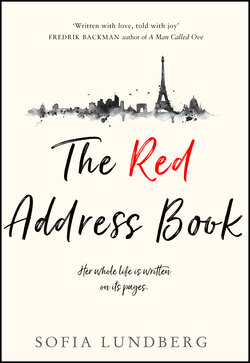

Читать книгу The Red Address Book - Sofia Lundberg - Страница 8

The Red Address Book

ОглавлениеA. ALM, ERIC

So many names pass by us in a lifetime. Have you ever thought about that, Jenny? All the names that come and go. That rip our hearts to pieces and make us shed tears. That become lovers or enemies. I leaf through my address book sometimes. It has become something like a map of my life, and I want to tell you a bit about it. So that you, who’ll be the only one who remembers me, will also remember my life. A kind of testament. I’ll give you my memories. They’re the most beautiful thing I have.

It was 1928. It was my birthday, and I had just turned ten. The minute I saw the parcel, I knew it contained something special. I could tell from the twinkle in Pappa’s eyes. Those dark eyes of his, usually so preoccupied, were eagerly awaiting my reaction. The present was wrapped in thin, beautiful tissue paper. I followed its texture with my fingertips. The delicate surface, the fibres coming together in a jumble of patterns. And then the ribbon: a thick red-silk ribbon. It was the most beautiful parcel I had ever seen.

“Open, open!” Agnes, my two-year-old sister, leaned eagerly over the dining table with both arms on the tablecloth, and received a mild scolding from our mother.

“Yes, open it now!” Even my father seemed impatient.

I stroked the ribbon with my thumb before pulling both ends and untying the bow. Inside was an address book, bound in shiny red leather, which smelled sharply of dye.

“You can collect all your friends in it.” Pappa smiled. “Everyone you meet during your life. In all the exciting places you’ll visit. So you don’t forget.”

He took the book from my hand and opened it. Beneath A, he had already written his own name. Eric Alm. Plus the address and phone number for his workshop. The number, which had recently been connected, the one he was so proud of. We still didn’t have a telephone at home.

He was a big man, my father. I don’t mean physically. Not at all. But at home there never seemed to be enough room for his thoughts. He seemed to be constantly floating out over the wider world, to unknown places. I often had the feeling that he didn’t really want to be at home with us. He didn’t enjoy the small things of everyday life. He was thirsty for knowledge, and he filled our home with books. I don’t remember him talking much, not even with my mother. He just sat there with his books. Sometimes I would crawl into his lap in the armchair. He never protested, just pushed me to the side so I didn’t get in the way of the letters and images that had caught his interest. He smelled sweet, like wood, and his hair was always covered with a thin layer of sawdust, which made it look grey. His hands were rough and cracked. Every night, he would smear them with Vaseline and wear thin cotton gloves as he slept.

My hands. I held them around his neck in a cautious embrace. We sat there in our own little world. I followed his mental journey as he turned the page. He read about different countries and cultures, stuck pins into a huge map of the world that he had nailed on the wall. As though they were places he had visited. One day, he said, one day he would head out into the world. And then he added numbers to the pins. Ones, twos, and threes. He was ordering the various locations, prioritising them. Maybe he was suited to life as an explorer?

If it hadn’t been for his father’s workshop. An inheritance to look after. A duty to fulfil. He obediently went to the workshop every morning, even after Grandpa died, to stand next to an apprentice in that drab space, with stacks of boards along each wall, surrounded by the sharp scent of turpentine and mineral spirits. My sister and I were usually allowed to watch only from the doorway. Outside, white roses climbed the dark-brown wooden walls. As their petals fell to the ground, we and the neighbourhood children would collect them and place them in bowls of water; we made our own perfume to splash on our necks.

I remember stacks of half-finished tables and chairs, sawdust and wood chippings everywhere. Tools on hooks on the wall; chisels, jigsaws, carpentry knives, hammers. Everything had its rightful place. And from his position behind the woodworking bench, my father, with a pencil tucked behind one ear and a thick apron of cracked brown leather, had a view over it all. He always worked until dark, whether it was summer or winter. Then he came home. Home to his armchair.

Pappa. His soul is still here, inside me, beside me. Beneath the pile of newspapers on the chair he made, with the rush seat my mother wove. All he wanted was to venture out into the world. And all he did was leave an impression within the four walls of his home. The highly crafted statuettes, the rocking chair he made for Mamma, with its elegantly ornate details. The wooden decorations he painstakingly carved by hand. The bookshelf where some of his books still stand. My father.