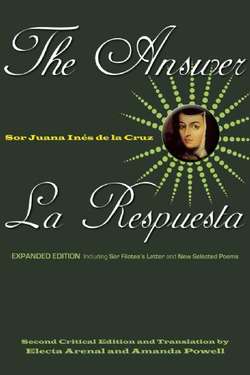

Читать книгу The Answer / La Respuesta (Expanded Edition) - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

I. Sor Juana’s Life and Work

Juana Ramírez / Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz 1648/51–1695): A Life Without and Within

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, author of the Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (as the Answer is titled in Spanish), is a major figure of Hispanic literature, but still little known to readers of other languages.1 Her poetry, plays, and prose move within and reshape the themes and styles of Renaissance and Baroque Spain and its far-flung empire. Indeed, she is considered the last great author of Spain’s Golden Age (Siglo de Oro), during which an extraordinary number of outstanding writers and artists were active.2 The emergent, differentiated, and multicultural New Spain—Mexico’s telling name during the colonial period—was fertile soil for Sor Juana’s imagination. In turn, her influence helped create a Mexican identity, contributing to the consciousness and sensibility of later scholars and writers.

Sor Juana’s prodigious talent, furthered by intense efforts that began in early childhood, produced a serious intellectual while she was still in her teens. She taught herself the forms of classical rhetoric and the language of law, theology, and literature. At every turn, from her courtly and learned yet marginalized standpoint, she contradicted—or deconstructed—artistic, intellectual, and religious views that would refuse her and others like her the right to express themselves.

The stratagems Sor Juana found useful for artistic and intellectual survival were so subtle that, given the continuity and pervasiveness of patriarchal values up to the present, the magnitude of her reinterpretations has often been missed or distorted even in our time. Sor Juana’s power reaches us today both in her revolutionary reversal of the gender identifications typical of her culture and in the beauty of her expression. With most aspects of the literary tradition of the Renaissance and Baroque at her command, she crafted exquisite poems. The ease with which she versified, the verve and versatility of her style, and the irony with which she applied her wit gave her an enormous literary mobility.

Similarly, her status as a rara avis (strange bird), while setting her apart from others of her sex and class in the public regard, made possible the physical and psychic space in which she thought and wrote. Respect for exceptionality was in part a reflection of the profound seventeenth-century interest in unusual natural phenomena that viewed artistic talent and intellectual drive in females as fascinating abnormalities. Sor Juana learned to exploit the fact that she was catalogued as a prodigy; she both defended and derided the hyperbolic terms of praise her exceptionality attracted (see the poem “Válgate Apolo por hombre!” [May Apollo help you, as you’re a man!]). Known to this day as the “Tenth Muse,”3 in her own time Sor Juana was also called the “Mexican Phoenix.” Such epithets of exceptionality, though common enough, kept Sor Juana on a pedestal, provisionally protected yet isolated amid the ceremony and turbulence of Mexico City. Praised and envied, criticized and acclaimed, for twenty-six years she wrote for the court and for the church as one of the most celebrated writers in the Hispanic New World.

Early Years: Country and Court. Juana Ramírez y Asbaje was born—in 1648 or 1651—in Nepantla, some two days’ travel from Mexico City by mule and canal boat, on lands her grandfather leased from the church.4 There, perhaps more than most of her contemporaries, Juana was exposed early in life to all levels of culture. She experienced music, art, and magic, native and imported. She heard the liturgy in Latin, cultured conversation in Spanish, and colloquial communication, including indigenous, African, and ranchero (rural) dialects. Juana’s grandfather, Pedro Ramírez de Santillana, was a learned man, although his daughter Isabel Ramírez, Juana’s mother, was not educated. His large library fed the young Juana’s appetite for reading. By the time her elders wished to still her curiosity, she had become so knowledgeable that they could neither put a stop to her restless quest nor convince her it was inappropriate. From book learning she drew authority and legitimacy for differing in her studious propensities, views, and aims from other Catholics, women, and learned Criollos.5 Society’s stigmas against marisabias (Mary-sages [female know-it-alls]) could not destroy her intellectual bent. The charm of Juana’s own account (given in the Answer) of how she could read soon after she learned to walk, how she took to rhyming as others take to their native tongue, and how she became competent in Latin shortly after taking up its study has in the imagination of readers outweighed her insistence that her prodigious learning reflected tenacious effort even more than a sharp memory.

Tenaciousness may have been one of her mother’s legacies. Isabel Ramírez was a strong and smart woman. Illiteracy did not impede her from managing one of her father’s two sizable farmsteads for more than thirty years. She had six children, three with Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, Juana Inés’s father, and three with Diego Ruiz Lozano; to neither man, she stated in official documents, had she been married.

Before the age of fourteen, Juana wrote her first poem. Knowing that women were not allowed to attend the university in Mexico City (Respuesta / Answer, par. 8) she made the best of an isolated, self-directed schooling: she devoured books initially in Panoayán, where the family farm was located, then at court in Mexico City, and finally in the voluminous library she amassed in the convent. A convent was the only place in her society where a woman could decently live alone and devote herself to learning. Her collection of books and manuscripts, by the time she gave it away for charity near the end of her life, was one of the largest in the New Spain of her era.

According to Diego Calleja, a Spanish Jesuit priest who wrote her earliest biography, the young Juana while at court submitted to a public examination of her already notorious intellectual gifts by forty of the most knowledgeable men of the realm.6 She defended herself, reported Calleja, “like a royal galleon attacked by small canoes.”7 Sor Juana’s poetry sometimes expresses mistrust and mockery of her many admirers and defenders for seeing her in their own image and for turning her into a circus rarity: “What would the mountebanks8 not give, / to be able to seize me, / and carry me round like a monster, through / byroads and lonely places” (¡Qué dieran los saltimbancos, / a poder, por agarrarme / y llevarme, como Monstruo, por esos andurriales! OC 1.147: 177–80).

Were she to be compared with anyone, her preference—implicit in the numerous parallels she draws in her poems—would be the learned and legendary St. Catherine of Alexandria, who had also been subjected to an examination and who had furnished ultimate proof that neither intelligence nor the soul were owned by one gender above the other. Some of Sor Juana’s last compositions were songs of praise to the saint (see Selected Poems, below).

Entrance into the Convent. Juana gave her age as sixteen when after five years as lady-in-waiting at the viceregal court of New Spain, she entered the convent in 1668 to be able to pursue a reflective, literary life. Sor Juana Inés, as she became known, claimed that her parents were married and that her birthdate was November 12, 1651. The church establishment officially required legitimacy for nuns; youth supported her reputation as a rarity. A baptismal record for one “Inés, daughter of the church,” however, dated December 2, 1648, is generally accepted as hers; it lists an aunt and uncle as godparents. This earlier date establishes her age as nineteen when she entered the cloister. Modern awareness of the revised birthdate hardly tempers the myth of young Juana’s precocity; she can be considered no less “a marvel of intelligence.”9

Sor Juana’s confessor, Antonio Núñez de Miranda, was not one who would graciously admit defeat before her prowess. A powerful, intelligent, and extremely ascetic man, Núñez was also confessor to the viceroy and vicereine and to many other members of the nobility. For him, as for those vanquished by St. Catherine, gender determined duty as well as destiny; the use of reason was an exclusively masculine privilege. In a world where females were associated with the Devil and the flesh, intelligent and beautiful women especially were blamed for all manner of ills; to lessen the threat to men’s uncontrollable passions, they should be sent to a nunnery to embrace holy plainness and ignorance. If Núñez considered the young Juana’s position in the limelight at court dangerous and untenable, her continued study and writing after entering the convent, especially on worldly subjects, he judged nothing short of scandalous. Indeed, Sor Juana protested his reportedly having said “That had you known I was to write verses you would not have placed me in the convent but arranged my marriage.”10

Núñez, not being a relative, had no legal right to dispose of her thus. At first Sor Juana bore the humiliation of his remarks, she tells us. But as she achieved recognition and patronage from a new viceregal governor and his wife, who were closely connected to the Spanish king, Sor Juana gained confidence in herself. Eventually, she responded angrily to Núñez and relieved him of his duties to her as confessor.

Now her ex-confessor, Núñez nevertheless continued to hold sway in Mexican society. Sor Juana’s ultimate clerical superior in Mexico, Archbishop Francisco Aguiar y Seijas, was a legendary misogynist.11 Her friend and admirer Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, the bishop of Puebla, donned the name “Sor Filotea” when he finally threw in his lot with those who demanded conformity. These three ecclesiastics wanted Sor Juana to stop writing and publishing with the latitude she had exercised. She was warned to be more like other women in the convents of Spanish America, who were supposed to serve as both subjects and agents of a regime undertaking massive imperialist endeavors. That is, nuns were to be subjects of the Spanish church and crown; to serve as agents of the church’s mission to Christianize heathens; to guard orthodoxy; and to ensure social obeisance. Beyond their spiritual roles, nuns—criollas like Sor Juana and even a few mestizas12—were also influential in economic, social, and educational spheres. They contributed to the arts, crafts, music, and cuisine of the larger community. They dealt in real estate, lent money, and employed servants and slaves, without whom most of their activities would have been impossible. Many nuns wrote. The very nature of a female community allowed them to develop voices that were separate from those of the priests and confessors who officially controlled their lives. Sor Juana, though, was unlike most other women in her intellectual ecumenism and religious rationality as well as her celebrity. She was envied and considered arrogant.

For centuries scholars refused to believe the reasons Sor Juana gave in the Answer for taking the veil. They speculated airily on some unfortunate love affair. Yet early and extensive readings in Christianity, the experiences of many of the women in her family (including her own mother), and not least her consuming interest in satiating her intellectual appetite easily explain her “absolute unwillingness to enter into marriage” (Answer, par. 9). She first tried the strictly ruled and aristocratic Carmelite convent, but she became ill and had to leave. Within a few months, after recovering, she entered the more relaxed Hieronymite13 convent of Santa Paula, where she found some of the tranquillity she desired for study—the real love of her life.

The cloistered Sor Juana spent the rest of her days (from 1668 until 1695) in quarters whose comfort and amplitude made them seem more salon than cell. Attended by several servants and for ten years by a mulatta slave her mother had given her,14 Sor Juana entertained numerous visiting aristocrats, ecclesiastics, and scholars, conducted wide but now lost correspondence with many others, and held monastic office as mistress of novices and keeper of the convent’s financial records. News of that service survived along with such details as her extraordinary brilliance as a conversationalist. Several contemporaries claimed that listening to her surpassed reading her work. Much of her poetry was destined to be heard. State and church officials commissioned all manner of compositions for the observances of holy days, feast days, birthdays, and funerals. Sor Juana earned not only favor but a livelihood—for each nun had a “household” to support—by fulfilling such literary orders.

It is not hard to imagine what a day in the life of Sor Juana and her convent sisters included. The daily patterns for all nuns were set by the rules of the order. Upon becoming brides of Christ they vowed chastity, poverty, and obedience; but just as in Rome, where luxury surrounded the higher echelons of church officialdom, austerity was the exception in religious houses established by royalty. Actual practice at the wealthy convent of Santa Paula was far from ascetic. Laxity, as it was called, characterized observance in most convents of Mexico and Peru. Nevertheless, the normal day was punctuated by prayer time: it began at midnight with matins; lauds followed at 5:00 or 6:00 A.M.; then came prime, terce, sext, and none, the “little hours” spaced during the day; vespers were said at approximately 6:00 P.M.; and finally compline at 9:00 or 10:00 at night. There would be recreation periods, a time, often, for needlework. Periodically, nuns would go on retreat to remove themselves from the hustle and bustle of normal monastic existence. Sor Juana, as she mentions in the Answer, would retreat from time to time, to study and write.

Regular intervals were set for community work, prayer, confession, and Communion. Many holy feast days interrupted routines, calling for special masses, meals, and festivities. Pomp and circumstance accompanied the taking of final vows. Music—singing and playing instruments—and theatrical performances provided inspiration, religious instruction, and entertainment at all such events. Sor Juana was probably among the most visited of the nuns at her cloister. In addition to family members she received dignitaries from around the world, most notably the viceregal couple. She would often be called to the locutorio (grate) to meet her guests, among whom on occasion were representatives of the cabildo (cathedral council) with writing commissions.

In unstructured moments, some nuns chatted and gossiped; others subjected themselves to penances. Capable and creative, Sor Juana took the advantageous circumstances of her life and an ability to “condense [conmutar] time,” as she phrased it, and put them to what she considered better use. Conservative elements within the church in Mexico preferred penances.

Conflict Intensifies. Troubles, as we have seen, had started almost from the beginning of Sor Juana’s time in the convent. For more than a decade after taking the veil, she kept still in the face of the reports that her confessor was voicing disapproval of her scholarly and literary activities, even when he claimed they constituted “a public scandal.” She outdid herself in public visibility, however, when in 1680, after showing initial reticence, she accepted the responsibility of devising one of two architectural-theatrical triumphal arches that were to welcome the new viceregal couple (the other was entrusted to her friend Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora).15 The ambitiously mythological artwork, inscriptions, narrative poems, and prose explanations of her “Allegorical Neptune” both established her reputation throughout contemporary society and, because of the extraordinarily public nature of the occasion, deepened the rift with Núñez.

At last, in 1681 or 1682, Sor Juana decided to take steps to ease her plight and relieve her pent-up animosity—the result, she said, of holding back her reactions to his animosity. She would exercise her right to engage a new confessor. The letter she wrote to Núñez, distancing herself from him, bristles with ironic and prideful sarcasm. “Not being unaware of the veneration and high esteem in which Y[our] R[everence] (and justly so) is held by all, so that all listen to you as if to a divine oracle and appreciate your words as if they were dictated by the Holy Ghost,” she writes, “nor unaware that the greater your authority, the more my good name is injured,” Sor Juana sees no alternative but to change confessors. “Am I perchance a heretic?” she asks, concluding with further rhetorical questions: “What obligation is there that my salvation be effected through Y.R.? Can it not be through another? Is God’s mercy restricted and limited to one man, even though he be as wise, as learned, and as saintly as Y.R.?”16 On her own path toward salvation, with a more sympathetic confessor, Sor Juana spent the next decade studying and writing her most enduring works. The viceregal couple continued to visit almost every day, on their way to or from vespers, until they returned to Spain in 1687.

Love Poems to Lovers of Poetry. With patronage such as the viceroy and vicereine provided, Sor Juana was free to persevere in being a learned and literary nun. This was not so unusual from the standpoint of a long, scholarly, and even at times worldly women’s monastic tradition, but it was certainly uncommon in her place and time. No doubt the churchmen were further scandalized by her “unchaste” writings, by what her poems indicated about a vividly imagined if not a lived experience. Only verses that transposed courtly love into a divine framework of religious ardor, and clearly mystical writing infused with eroticism, were deemed orthodox by the censors. Sor Juana’s courtly yet personal poetry enlisted the Renaissance conventions of troubadour love lyrics and Petrarchan sonneteering to express deeply felt earthly friendship, kinship, and sexual attraction.

Little can be known directly about Sor Juana’s intimate loves, though speculation abounds. Finding that she wrote with an acute understanding of lovers and their emotional travails, readers have been convinced that she knew whereof she spoke. Did she have suitors at court? Did she suffer first-hand the sort of abuse and loss some descry in her poems? Was she in love with a man or men? With a woman or women? Biographical documentation is lacking. Her poetry attests first that she knew well the expectations of literary practice on these topics, and second, that the deepest personal ties she expressed were those to two recognizable figures: Leonor Carreto and María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, two vicereines (wives of the viceroys) of New Spain.

The social distance between Sor Juana and these two noblewomen, whom she wrote of lovingly and also served, was not unlike that of the Provençal troubadours (men and women) and their lords and ladies. That very distance allowed the poet to be explicit in expressing affection, providing a public barrier to the realization of such sentiments. These were widely perceived as relationships that could not be consummated. What other forms, besides the written, her expressions of feeling may have taken remains unknown. No one denies that Sor Juana displayed in her writing depths of emotion and erotic desire associated for us with intimate relationships.17

Notably, her most ardent love poems were dedicated to the two vicereines mentioned above. Well-educated and sophisticated readers, it was they who most energetically encouraged her scholarly and literary pursuits. When the first of the two aristocrats, the vicereine Leonor Carreto, Marquise de Mancera, died in 1674, Sor Juana had been in the convent for six years. But for almost the same number of years immediately before her entrance in the convent, Juana had been in Leonor’s service—a favorite companion at court. Sor Juana used the literary “Laura” as the marquise’s name in poems:

Death like yours, my Laura, since you have died,

to feelings that still long for you in vain,

to eyes you now deny even the sight

of lovely light that in the past you gave.

Death to my hapless lyre from which you drew

these echoes that, lamenting, speak your name,

and let these awkward characters be known

as black tears shed by my grief-stricken pen.

Let compassion move stern Death herself

who (strictly accurate) brooked no excuse,

and let blind Love lament his bitter fate;

who boldly hoping at one time to woo you

wanted his sight restored that he might see you,

but finds his eyes are useless save to mourn you.

(OC 1.300–301, trans. Amanda Powell)

Mueran contigo, Laura, pues moriste,

los afectos que en vano te desean,

los ojos a quien privas de que vean

hermosa luz que un tiempo concediste.

Muera mi lira infausta en que influíste

ecos, que lamentables te vocean,

y hasta estos rasgos mal formados sean

lágrimas negras de mi pluma triste.

Muévase a compasión la misma Muerte

que, precisa, no pudo perdonarte;

y lamente el Amor su amarga suerte,

pues si antes, ambicioso de gozarte,

deseó tener ojos para verte,

ya le sirvieran sólo de llorarte.

This elegiac sonnet gives rein to Sor Juana’s grief, implying a literary as well as affectionate relationship. It is one of three sonnets that issued from her sorrow over the loss of the woman who her first biographer, Calleja, claimed, “could not live an instant without her Juana Inés.”

Similar terms were used to describe her next long relationship of devoted friendship. To Vicereine María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, Marquise de la Laguna, Countess de Paredes, who became “Phyllis” in the poems, Sor Juana wrote:

… like air drawn to what is hollow,

Like fire, to feed on matter,

Like boulders tumbling to the earth,

and intentions, to their goal;

indeed, like every natural thing,

—all united by the desire

to endure, which ties them tight

in bonds of closest love…

But to what end do I go on?

Just so, Phyllis, do I love you;

with your considerable worth,

this is merely an endearment.

Your being a woman, your being gone

cannot pose the slightest hindrance

to my love, for you know that our souls

have no gender and know no distance.

(OC 1.56–57:97–112, trans. Amanda Powell)

como a lo cóncavo el aire,

como a la materia el fuego,

como a su centro las peñas,

como a su fin los intentos;

bien como todas las cosas

naturales, que el deseo

de conservarse, las une

amante en lazos estrechos …

Pero ¿para qué es cansarse?

Como a ti, Filis, te quiero;

que en lo que mereces, éste

es solo encarecimiento.

Ser mujer, ni estar ausente,

no es de amarte impedimento;

pues sabes tú, que las almas

distancia ignoran y sexo.

María Luisa, Marquise de la Laguna, was a frequent visitor at the convent during the seven years she spent in Mexico, and she was an avid supporter of Sor Juana. It was she who took Sor Juana’s poems to Spain and arranged for her first book to be published. With the exceptionally successful appearance of Castalian Inundation in 1689, the poet’s celebrity grew in educated circles throughout Spain and its colonies (including the Philippines).18 To the chagrin of many of her superiors, spurred by her own great gifts and by María Luisa’s instrumental patronage, Sor Juana flourished as a literary figure of the Spanish-speaking world.

Gradually, however, other factors began to weigh more heavily than viceregal support and fame. As the seventeenth century reached its last decade, Sor Juana’s situation and that of New Spain veered drastically. Economic, social, and political crises engulfed the realm. Nature itself seemed bent on intensifying the troubles. A solar eclipse spread fear among the population, crops not devastated by rain in the countryside were eaten by weevils, and floods inundated Mexico City. Speculation and hoarding worsened the scarcity of fruit, vegetables, maize, bread, firewood, and coal. Rising prices touched off spontaneous protests. The viceregal palace and municipal building were set on fire. Punitive responses triggered panic, further rioting, penitent religious processions, and executions. Sor Juana’s most significant supporters had returned to Spain or had fallen out of favor. The pressures mounted—perhaps in her own mind as well as from without. Her writing, on religious and mundane subjects alike, came under more direct fire.

The Bishop, the Answer, and—Silence. If it was irreverent for a nun to write love poems, it was worse for her to meddle in theology. For Sor Juana’s biography and for the study of her writing, the significance of the “Letter Worthy of Athena,” this nun’s one incursion into theological argumentation—the only one in prose, written down and printed, that is—resides as much in its having heightened the envy and antagonism of the ecclesiastic establishment as in its admirable reasoning and style.

Piqued by Antonio Vieira’s claim to have improved on the arguments of the fathers and doctors of the church19 (viz., Sts. Augustine, Thomas, and John Chrysostom) concerning Jesus Christ’s highest favor to humanity, Sor Juana in 1690 had ventured to refute the famous preacher’s “Maundy Thursday Sermon” (written forty years earlier!). The refutation was heard in a conversation with guests at the convent, among them Bishop Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, who was on a visit to Mexico City. At his behest, she wrote down her critical disquisition disputing Vieira’s argument as to the highest example of Christ’s love. Three times she mentions her trust that the text will be seen only by the bishop’s eyes; she invites his correction and claims that, not having had the time to polish it, she remits it to him en embrión, como suele la osa parir sus informes cachorrillos (“in an embryonic state, just as the bear gives birth to her unformed cubs,” OC 4.434:904).

Her double-edged claims of humility did not obscure the virtuosity of her argumentation, or her skill at logic. Was the bishop conspiring to silence her when he requested a written copy? He had long been an admiring friend, but he was also an official of convent governance, known for inspiring nuns with fanatical piety. He, too, must have been distressed by this, in his eyes, arrogant and wayward daughter. For years Archbishop Aguiar y Seijas and Fr. Núñez had sought to command from Sor Juana behavior more befitting a nun. Now, they were poised for their chance. Wittingly or unwittingly, the bishop of Puebla joined forces with them.

With the viceroy and vicereine gone, ecclesiastics may have found it easier to instigate or fuel the storm of controversy that broke out over the “Letter Worthy of Athena,” as the bishop of Puebla titled her critique when he delivered it to the press, appending a letter signed “Sor Filotea” as a preface. Ambivalent and ambiguous enough to have confused many generations of readers, the bishop’s letter was for Sor Juana a purportedly friendly—and therefore wily and more painful—attack. It prompted her to explain and defend herself as she never had before—to write the Answer to Sor Filotea de la Cruz, the only avowedly self-descriptive piece of prose she produced. For her, the printed letter from the bishop of Puebla disguised as Sor Filotea, with its pretense of saintly guidance (St. Francis de Sales had used the same pseudonym to write to nuns), served as a public admonition and delivered a threat of persecution. Some scholars assume that the letter produced in Sor Juana a combination of anger, resentment, shock, hurt, contempt, and fear, and that these emotions precipitated a decision to silence herself that had already been forming within her.20 In any case, in the three months it took to write the unusual reply to “Sor Filotea,” Sor Juana created a text we now consider essential to a full understanding and appreciation of her genius.

From Spain the former vicereine, María Luisa, followed the events that seem to have led the poet to silence herself in the face of discouragement and inquisitional mentalities. The aristocratic Spaniard did all she could to come to the rescue. When the manuscript of Sor Juana’s theological critique was circulated in Spain, many people took the nun’s side or at least defended her right to argue. In Mexico, where Vieira was greatly favored by the Jesuits, Sor Juana was refuted with virulence, although she also had a few defenders. In Spain, the former vicereine marshaled seven respected theologians to praise the Crisis [Critique], as Sor Juana’s refutation of Vieira was now called. Disregarding the bishop of Puebla’s hyperbolic title (“Letter Worthy of Athena”), the marquise had it reprinted along with defenses and numerous poems of praise for Sor Juana, “Phoenix of America.” The laudatory pages comprised the initial third of the second volume of Sor Juana’s Obras [Works], a book that the author herself had cooperated in preparing so that some of her finest writing would see print. Behind the “Knight of the Order of Santiago” to whom Juana Inés was asked to dedicate the volume stood the tireless efforts of the ex-vicereine, who expedited publication in Seville, where she and her husband had considerable influence. But the paeans to Sor Juana’s talent and glory that prefaced this 1692 volume probably backfired, causing Sor Juana even more problems with her superiors in Mexico.

That same year, in 1692, Sor Juana sold her library and musical and scientific instruments, contributing the proceeds to charity. She wrote her last set of villancicos (carols), those to St. Catherine. Little more would come from her pen. Two years later, in 1694, she renewed her vows, signed a statement of self-condemnation, and reportedly turned to penance and self-sacrifice.

Was Sor Juana’s retreat from writing, study, and society a religious conversion? Was she under compulsion? How much the pressure came from without, how much from within is rigorously debated by scholars. It is notable that, at the end, Sor Juana took the ascetic path Núñez had earlier prescribed. In fact, in 1693 he became her confessor once again. Sor Juana’s life ended two months after his, in 1695, when she fell victim to an epidemic while caring for her sisters.21 The last of her three volumes of work was not published until five years later, in Madrid, in the first year of the new century.

A Poet-Scholar: Sor Juana’s Writing

Humorously quoting Ovid, Sor Juana described herself as a born poet—when she was spanked, her cries issued forth in verse—and claimed that she first spoke in rhyme and then had to learn to speak in prose. Part of her modern appeal resides in the amazing skill and grace with which she uses language. Her very survival as an exception, a courtly churchwoman, and her productivity and excellence as a writer, required adept handling of Mexico’s multiple linguistic codes, its ways of seeing and putting things—cultured and popular, legal and literary. Like her “father” St. Jerome, she read books, the world, and, to a lesser extent, people in classical as well as Christian terms. She absorbed, but as a female reader also resisted, the words of the ancients—the classical writers of Greece and Rome—and of the Bible and the church fathers as well. In writing she interpreted and revivified their style and thought, applying them to what was most relevant for her. She knew and emulated or mimicked such Spanish authors as Cervantes, Quevedo, Góngora, Lope de Vega, and Calderón de la Barca.22

Living in a world of real and verbal mirrorings, conscious of the specular role assumed involuntarily by women, Sor Juana crafted poetic mirrors and lenses that continue to reveal the submerged realities of her times. Her work reflects how actively the masculine culture assigned women secondary, invisible, silently reflective roles in society. Indeed, the poet frequently manipulated images of reflection and its associated phenomena. She painted portraits in words: to express love of María Luisa Manrique de Lara, to ridicule the preposterous exaggerations used to describe women in poetry, to disparage the expectation that women never age. Men put up mirrors, she showed, to view what they wanted to see. Hers bore a different image.

Sensitive to the reproduction of hierarchies in emblematic and rhetorical renditions of the various social and divine estates (such renditions circulated widely at the time), Sor Juana replaced figures at strategic points along the traditional echelons.23 She included the Virgin Mary, for example, in references to the Trinity, placing her at the pinnacle of the sacred and even the poetic pyramid; she traced a holy female lineage that went through Mary back to Isis; she sanctified Mother Nature and Discourse—language—itself. The widely accepted custom among Mexicans of expressing ardent reverence for their patron, the Virgin of Guadalupe (unacknowledged descendant of a Nahua mother goddess), provided a cover for Sor Juana’s at times almost heretical and pantheistic redeifications.

Colloquial and cultured, Sor Juana’s verse skillfully spoke to audiences throughout her vastly diverse society. The Catholic church therefore sought out her empathetic voice, her capacity to bring religious thought and legend to life and to make it playfully meaningful, comissioning her to write texts (villancicos) for holyday masses. To this day, nearly every schoolchild in Latin America learns stanzas from “Hombres necios que acusáis” [You foolish and unreasoning men],24 Sor Juana’s most popular poem.

Sor Juana’s verse spans the sublime and the frivolous and combines the languages of court and convent, Scholasticism and literature, medieval dogma and modern rationalism. A student of symbol and logic, she employed both in structuring works sacred and profane, dramatic and comical. She wrote burlesque sonnets, words for local dance tunes, and occasional poems to accompany gifts, as thank-yous, as entries to the numerous poetry contests, as celebrations of baptisms, birthdays, or the completion for a doctorate, and for inaugurations of churches. For her poems on love, jealousy, quarrels, absence, and yearning, she was favorably compared to the greatest poets of Spain.

Sor Juana’s complete works include sixty-five sonnets (including some twenty love sonnets, deemed by many to be among the most beautiful of the seventeenth century); sixty-two romances (of a style similar to ballads); and a profusion of endechas, redondillas, liras, décimas, silvas, and other metrical forms employed during Spain’s literary Golden Age.25 For dramatic performance, Sor Juana wrote three sacramental autos (one-act dramas) and two comedies (one a collaboration). In addition, she composed thirty-two loas (preludes to plays) that were sung and performed as prologues to the plays, as well as separately for religious and viceregal celebrations; two sainetes (farces) and a sarao (celebratory song and dance), performed between the acts of one of the plays; and fifteen or sixteen sets of villancicos (carols) for matins. Each of the last-mentioned contained eight or nine songs, elaborations of such religious themes as the Nativity of Christ, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and legends of Sts. Joseph, Peter, and Catherine of Alexandria.

In sketching Sor Juana’s biography we spoke of the “Allegorical Neptune,” the triumphal arch in honor of the arrival of the viceregal couple, the Marquis and Marquise de Mancera. A lesson in statehood, a guide to good government, the corresponding text alludes to the virtues princes and kings ought to possess, and it ascribes the Greco-Roman god Neptune’s beneficence to the teachings of his mother, the Egyptian goddess Isis.26 The viceroy is urged to be praiseworthy both as a husband and as a ruler; welcome is extended to the vicereine, and the ruling couple is spoken of as a unit. In her prose commentary Sor Juana expatiates on the complexities of symbolic language as used by the Egyptians, offering cues, in the process, to her own alchemical sympathies; meanings appear in multiple layers and are accessible according to the reader’s level of insight, intelligence, and initiation.

Sor Juana’s 975-verse First Dream (referred to in the Answer simply as Dream) is generally considered the most important philosophical poem in the Spanish language. This symbolic, mirror version of the Answer had long been read as a poem of intellectual disillusionment. More recent readings see it as an exploration of “the available modes of human knowledge from the geometrical movements of celestial bodies to the intricate workings of the human body, through induction, logic, and intuition, all revealed as inadequate in the waking world,” and also as a refutation of “both the theory and the practice of objectifying women.”27 Critics today celebrate its originality and modernity, admire its statement “in favor of the human spirit’s right to unimpeded growth,”28 and proclaim “its vision not unlike Descartes’s… a fusion of theology, poetry, and science.”29

Dream, it should be noted, is the poem that Sor Juana herself most respected. It is an exaltation of the poet’s insatiable thirst to encompass all human knowledge:

Not being able to grasp

in a single act of intuition all creation;

rather by stages, from one concept to another ascending step by step…

(OC 1.350:590–94)

Sor Juana combined unparalleled skill—a seeming verbal magic—with a profound and woman-centered vision. Her originality lies in this combination: in the literary forms she gave to her insatiable, gender-conscious, intellectual curiosity. Sor Juana was passionately inquisitive about empirically observed phenomena and cognizant of the changing relationship of human beings to their environment that marked the dawning of the scientific age. She knew and wrote about the ancient pharmaceutical potions of the Greek physician and anatomist Galen (A.D. 130?–201?) and also mentioned indigenous Mexican herbal cures. With visitors from other parts of the Americas and from Europe she pondered and discussed astronomy, mathematics, mechanics, and medicine. She studiously pursued a knowledge of music and painting. All these concerns—her preoccupations and delights—found their way into her poems and prose.

Sor Juana’s Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz is often referred to as “autobiographical.” It might better be described as a rhetorically structured letter of self-defense. “Self,” however, is a term of our time and culture, not hers.30 In her differently psychological and thoroughly mannered religious age, the “self” she defends cannot be located in an “inner nature” or “consciousness” outwardly expressed. Rather, the author is defending a dearly held intellectual position, which is her concept of how theology can best be done: by studying the arts and sciences and by including women both as subjects of study and teachers of other women. In the following section, we present a detailed consideration of the many elements composing this complex text.

II. La Respuesta / The Answer: A Reading

This section presents essential elements of the immediate context, purpose, and style of Sor Juana’s Answer. Throughout, we aim to help the reader understand how Sor Juana made use of conventions available to her writing, where she was innovative, and how thoroughly her gendered sense of the world and of language permeates her text.

Sor Juana’s Art and Argument

Counterpoint typifies the structure of the Answer to Sor Filotea de la Cruz. In keeping with the Baroque literary context of the period and the complex urgency of Sor Juana’s purpose, the piece is polyvocal and polysemous—of multiple voices and meanings. Understanding requires that the reader perform several acts of “translation” and exercise a willingness to accept ambiguous complexity.

For many years the essay was read as a relatively straightforward text. Almost nothing the bishop wrote to Sor Juana, however, including his signing of the letter as “Sor Filotea,” nor anything Sor Juana answered, particularly regarding her place in the order of things, can be taken wholly at face value. The elaborate quality of the rhetoric makes simple readings insufficient. Letter, legal defense, treatise, and autobiographical essay,31 the Answer displays traditional learning and demonstrates the need for freedom of experimentation and opinion. For educated readers of the time, Sor Juana’s methods were familiar, but her message was pioneering; for us, only the message is familiar. We must keep in mind that like a classical ballet, the essay is carefully choreographed and costumed; it is at once sincere and strategic, simple and subtle.

Multiplicity of Meanings. Sor Juana’s prismatic method explores and exploits the interplay among words, their etymological roots and cognate forms, their denotations and connotations. For instance, especially in paragraphs 17 and 21 of the Answer, Sor Juana highlighted the cluster of Spanish words seña, señalar, señalada/o (whose meanings include, respectively, “sign,” “signal/ signify,” “significant”) that are related to the Latin signum (“sign, mark”; “token”; “miracle”). She plays on etymological connections between these words to describe the vulnerability of intelligence and poetic talent. In Christ she saw the quintessential model of intelligence and beauty. By citing the “signs” worked by Christ in the Gospels—“acts of a miraculous nature serving to demonstrate divine power or authority” (OED)—she inveighed against the persecution and vituperation that commonly victimize outstanding or “significant” human beings. Thus, outstanding powers of mind she likened to such “signs” of divine workings, to the miraculous. At the same time, in current terms, she underscores the functions of language as a system of signifiers and as a potent ideological force. Though unfairly fragmented, an excerpt will nevertheless serve as example:

…as for this aptitude at composing verses … even should they be sacred verses—what unpleasantness have they not caused me…. [A]t times I ponder how it is that a person who achieves high significance—or rather, who is granted significance by God … is received as the common enemy…. and so they persecute that person…. [In Athens] anyone possessing significant qualities and virtues was expelled…. [Machiavelli’s maxim was] to abhor the person who becomes significant…. What else but this could cause that furious hatred of the Pharisees against Christ? … O, unhappy eminence, exposed to so many risks! O sign and symbol, set on high as a target of envy and an object to be spoken against! (pars. 17–22)

Through the words and concepts sign/signify/significance, Sor Juana threads together ideas and analogies that are both simple and complex. The ideas concern language, human psychology, theological interpretations, power struggles, and threats to social structure. The analogies include connections drawn between pre-Christian (Hebrew, Greek, Roman) and Christian history and custom, between the Pharisees and the Mexican church hierarchy, between poetry and the accusation of blasphemy, and, not least, between Sor Juana and Christ.

Throughout the Answer as a whole, we can only guess at some points, jibes, and arguments Sor Juana makes, for we lack documents that would give us a fuller portrait of her involvement with the intricacies of the power struggles among and between Jesuits, bishops, Spaniards, and criollos. We do know about the struggle between Sor Juana and two church authorities (Núñez, the dismissed confessor, and Fernández, the bishop) with whom she had very close ties. But her formally educated contemporaries had an advantage, an everyday familiarity with both the Bible and classical mythology that we lack and that provided them with clues to coded meanings. When Sor Juana cited a passage or alluded to a mythological personage, her readers could contextualize immediately as we cannot, except by study. They would know what came before and after, who was related to whom, the significance of frequently used figures. Therefore, many more implicit meanings were probably understood in the author’s time and are not now. On the other hand, some levels of meaning may be clearer to twentieth-century readers than they were to Sor Juana’s contemporaries. Both she and we are conscious of discourse as an (en)-gendered process—that is, of attitudes about sex roles hidden in speech. We know that “mankind” both includes and hides women. We have learned, as she did, to cross boundaries and read between the lines.

Narrative Modes. Sor Juana disposes the elements of style with such ingenuity that they provide protective covering for her derision of stupidity and her attack on injustice. Too, this reasoned structure is partially obscured by the polite flourishes of Mexican formality and the conceptual wit of Baroque fashion. The classical structuring form follows the rules for writing and speaking set down by Greek and Roman rhetoricians and exemplified with citations from great writers and orators.

Both intensely personal and consciously public, the Answer is based on patterns of expression and composition set by the leading male figures of classical antiquity and early Christianity. But it also includes use of narrative modes common to women’s religious writing of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the sermon, Renaissance legal and rhetorical discourse, and high literary forms of her day. Polish and intricacy in mixing the style of the Baroque with earlier Christian and classical conventions contribute to the Answer’s strength and durability.

Sor Juana imitates the traditional nun’s vida (Life), “obediently” examining and confessing her conscience. She parodies elements of hagiography—saints’ lives—which the bishop was accustomed to read and which were expected in writings by nuns. Sor Juana likens herself to St. Teresa of Avila, insisting on the fact that they are both writers and women who rejected marriage. Indeed, there are parallels she did not state: both women deftly maneuvered in and around difficult situations with the church hierarchy and male superiors; both had friends in powerful places. Further, from our modern-day perspective, both have long been honored in Spanish letters. Despite her familiarity with convent style and her specific references to Teresa, there are limits to a comparison between the two. The Spaniard was a mystic; the Mexican, a scholar. Sor Juana did not found monastic houses for women or reform a religious order. She saw the convent as the least noxious of her options, twice saying so and twice finding it necessary to hedge that bold statement with an assurance of her respect for the religious state (pars. 9, 13). It is an intellectual calling, not a mystical or even a spiritual vocation, of which she gives an account. Sor Juana’s quest—not unlike the Woolfian room and income of one’s own—was for the time and the means necessary for creative reflection. Yet she employs the same stratagems of staged weakness and innocence (pars. 5, 13, 14, 34), of subterfuge, with which writing nuns negotiated ecclesiastic minefields. (See the section “Classical Rhetorical Models,” below, for further discussion of the conventions of religious language.)

By her account, Sor Juana’s wonder at God’s creation comes not through vision or revelation but through empirical observation and deduction; thus the natural, material world provides its own evidence of worth as God’s creation. With literary and theatrical flair (and significant topical influence, as Frederick Luciani has shown) she takes us through the tale of her early childhood, skipping her court years. Amazingly, her text raises women’s “ways of knowing” to the same level as the noble ancient science of philosophy and the emergent fields that were establishing new scientific principles.

Sor Juana also demonstrates a command of the sermon, one of the most popular forms of the period, in her impassioned reenactment of the scene from Calvary. She implies, in the tradition of the imitatio Christi (imitation of Christ), that her suffering was like Christ’s, making her judges’ charges against her seem as atrocious and deplorable as those hurled at Jesus. Thus, Sor Juana compounds her knowledge of biblical material, presented in sermon form, with the form of classical juridical appeal. Such appeals to emotion, she has learned from her study of classical rhetoric, are “necessary if there are no other means for securing the victory of truth, justice and the public interest.”32 Sor Juana’s distinctive “public interest” was the intellectual plight of women in her own time.

The Answer, pulling together strands from sermonic, biblical, and legal as well as literary genres, brings the tradition of humanist moralism to Mexican theology and anticipates a later genre, the polemical essay. It is significant that the Spanish writer Baltasar Gracián is the only male literary contemporary whom Sor Juana mentions in the Answer. A moralist, he was interested in the ethics of social behavior and associated with the most idealistic and cultured exponents of Hispanic letters. As a stylist and rhetorician he defended the conceptistas, poets who displayed intellectual, at times satirical, wit.

Rhetorical Forms. Sor Juana sets the stage for one of her last battles of wits with a battery of precise rhetorical strategies. She knows the rules and conventions governing literary, theological, exegetical (pertaining to exegesis, the detailed explanation of biblical texts), logical, epistolary (pertaining to formal letter writing), and juridical discourse—and she will use them. The essay is in fact and in appearance an epistolary text and follows strict patterns of presentation, well known in her time to those (men) with university training.

Religious Epistolary Address. Readers are liable to find some of the author’s stances, especially at the beginning and end of the Answer, both mystifying and off-putting. What appear to modern and secular eyes as self-deprecation, exaggerated humility, and convoluted politeness are more accurately understood as conventions of the age, standard modes of address among religious women and men, and courtly manners of a highly stratified colonial society. In Sor Juana’s day, formal letter writing was governed by strict rhetorical rules, including Renaissance adaptations of Greek and Latin models. (Vestiges of such rules are quite apparent today in French forms of address in letter writing; early in the twentieth century, formal English-language letters were still ended with the metaphorical “Your humble servant.”) Epistolary prose and verse were fashionable literary genres. Writing by nuns and clerics, especially when addressed to their superiors, followed established modes that included such metaphors of humility as “I lowlier than a worm” and, as Sor Juana wrote in a document on the Immaculate Conception of Mary: “I … the most insignificant of the slaves of Our Lady the Most Holy Mary” (OC 4.516). Finally, such expressions as “I could give you a very long catalogue of [my verses] … but I leave them out in order not to weary you” (par. 28), follow the standard avoidance of fastidium (tedium), as required by manuals of epistolary and forensic rhetoric.

Classical Rhetorical Models. The overall organization of the Answer is based on classical explanations of “the order to be followed in forensic causes [legal arguments].”33 It shows Sor Juana’s absorption and application of the Greek and Roman teachings of Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, and Quintilian (see annotations to pars. 1, 5, 23, 42). Sor Juana was convinced that in pursuing causes “which present the utmost complication and variety … [one had to become thoroughly versed in] the function of exordium, the method of the statement of facts, the cogency of proofs, whether we are confirming our own assertions or refuting those of our opponents, and the force of the peroration, whether we have to refresh the memory of the judge … or do what is far more effective, stir his emotions.”34 In accord with this model, the basic divisions of the Answer are as follows: after the introductory exordium (pars. 5–6), she moves into the narration (pars. 7–29); the proofs or arguments (pars. 30–43) precede the concluding peroration (pars. 44–46).35 Thus, although she is vulnerable to the accusations of her two “fathers” (Núñez, her former confessor, and Bishop Fernández, her erstwhile friend), in the Answer Sor Juana spiritedly demonstrates to them that men (triumphant conquerors, par. 43) are in much greater danger than women of falling prey to arrogance and illusions of grandeur, despite common prejudice to the contrary. Presumption and envy are similarly handled.

Quintilian was perhaps the most significant among the great teachers-of-teachers whose advice Sor Juana followed and whose methods she practiced in acquiring her much-prized reading and speaking skills.36 The first of the seventy-odd citations in the Answer (see par. 1) is from his Institutio oratoria. So is the strategically cited dictum “Let each one learn, not so much by the precepts of others, as by following the counsel of his own nature” (par. 39; emphasis added). With this quote she caps the paragraph that precedes the climactic rhetorical question of the essay:

If my crime lies in the “Letter Worthy of Athena,” was that anything more than a simple report of my opinion, with all the indulgences granted me by our Holy Mother Church? (par. 40)

On this phrasing lies the force not only of her own case, but the claim of all women, of “each one,” to interpretive power. To classical teachings of rhetoric and pedagogy she adds the weight of Hebrew and Christian authority, which she emphasizes (following the grammatical gender of Spanish) as maternal. Thus, by following the highly conventional authority of Quintilian, in addition to espousing educational individuality and freedom of opinion, she is able to move the whole edifice of culture under the roof of a “Mother Church” that, she avers, is permission-giving and not withholding. An earlier reference to Christ’s “Mother the Synagogue” (par. 23) and the one to “our Holy Mother Church” cited above are part of Sor Juana’s recurrent association of motherhood with creativity and wisdom.

Through all these modes of discourse, Sor Juana expresses pain, regret, and anger regarding her personal situation. She praises, begs, rejects, persuades, ridicules, chides, defends, and teaches the bishop and the imaginary jury—her future readers. She plays every role, accused and accuser, subject and superior. She asks the bishop to put himself in her place, and then rhetorically puts herself in his, thus challenging the hierarchical order. Finally, not forgetting her officially inferior position, she insists on her spiritual equality and on exercising her God-given reason, poetic gifts, and free will. In the process, she displays her intellectual peerlessness while mouthing the expected clichés of the rhetoric of feminine ignorance and tendering the requisite offer of retraction, should anything be said that might be condemned as heresy.

The Issues at Stake

To understand the letter Sor Juana wrote in 1691, it is necessary to know something of two other letters preceding the Answer. She wrote one; the other, by the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz—“Sor Filotea”—was the letter to which she was most immediately replying in the Answer (see Appendix). The circumstances surrounding the composition of these two earlier letters were discussed in the sections “Conflict Intensifies” and “The Bishop, the Answer and—Silence,” above; we return to the letters here to explore their content.

Letter to Her Confessor. The first letter was written by Sor Juana in 1681/82 (i.e., a decade before the Answer) but was not recovered until 1980. Sor Juana did not intend it for publication.37 In it, she addressed her confessor of more than a decade, Antonio Núñez de Miranda, one of the most knowledgeable and influential citizens of New Spain.38 The letter relieves him of his responsibilities to her for absolution of sins and spiritual guidance—in essence “fires him”—a right every nun had been assured of since the Council of Trent (1545–63). Going beyond personal appeal, Sor Juana’s letter criticizes the narrow-mindedness and repressive authoritarianism, the un-Christian and unintelligent dogmatism of the whole imperial establishment, including that of other nuns and laywomen, young and old. The recently recovered letter thus gives us a new view of the political and hierarchical tides Sor Juana had to ride as well as some notion of how she kept them from overwhelming her.

From the first lines of the letter to its conclusion, irony and rhetorical questions heighten Sor Juana’s outrage. Specific themes and rhetorical devices (indeed, actual statements and questions) made later in the Answer are already posed in this private letter to Núñez: for example, regarding her right to write poetry and to study and her concern for the sanctity of her soul.

This letter of 1681/82 is the source of the most concrete and unadorned information about Sor Juana’s activities that we have from her own pen—the “who, what, and when” with regard to support for her Latin and music lessons, the provision of her dowry to enter the convent, her receiving visitors, and the commissioning of several writings such as the Allegorical Neptune. Sor Juana attacks Núñez’s reputed remark, that had he known she would write poetry, he would have “married her off” rather than put her in the convent. “Indeed, my most beloved Father,” she replies, “…what direct authority was yours, to dispose either of my person or my [free] will?” She makes clear that her godfather paid her dowry: Núñez had no such power, although she acknowledges “other affectionate acts and many kindnesses for which I shall be eternally grateful.” The personal information given privately to her confessor contrasts sharply with such frequently considered passages as Sor Juana’s love for her convent sisters and theirs for her and other selectively anecdotal autobiographical sections of the 1691 Answer. Thus, when Sor Juana’s two letters are examined together, the Answer’s “autobiographical” passages reveal theatrically heightened and fictionally selective motifs and demonstrate the artfully constructed nature of the later, intentionally public essay.

Letter from “Sor Filotea.” The second letter necessary for an understanding of the Answer to Sor Filotea de la Cruz delivered praise, censure, and admonishment from one “Sor Filotea.” As we have seen, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, bishop of Puebla, wrote that letter and signed that pseudonym when he had it printed in 1690 as a preface to Sor Juana’s “Letter Worthy of Athena.” The Answer is a point-by-point retort to the bishop of Puebla, yet few have considered the Answer in this light. Much of what Sor Juana says and how she says it was determined by her reaction to his letter. (See Appendix, pages 222–231, for full text of this letter.)

The central tenet of the bishop’s prefatory letter to Sor Juana is that all but divine knowledge should be eschewed, especially by a woman. The humanities are useful only as “slaves” to sacred studies. “Filotea” does not believe women should be barred entirely from learning, so long as learning does not keep women from assuming “a position of obedience” or incline “our sex” to presumptuousness. The bishop (in female disguise) warns Sor Juana:

I am quite certain that if you … were to form a detailed idea of divine perfections (which is allowed us, even amongst the shadows of our faith), you would at one and the same time find your soul enlightened and your will set aflame and sweetly wounded by the love of God, in order that the Lord, who has so abundantly showered Your Worship with positive favors in the natural world, should not be obliged to grant you only negative ones in the hereafter. (OC 4.696 and Appendix, below.)

Accompanying this threat to the salvation of Sor Juana’s eternal soul are the bishop’s admonitory references to several great (male) religious figures who spurned all worldly learning. By way of answer, Sor Juana will cite other figures, male and female (or the same men, at different periods in their lives), who embraced secular as well as sacred studies. In paragraph 11, she implicitly scolds and ridicules the bishop, demonstrating her complex understanding of the limits to what we today call binary oppositions: “In sum, we see how this Book [the Bible] contains all books, and this Science [of theology] includes all sciences, all of which serve that She may be understood.” She protests compartmentalization and argues for the continuity of knowledge, sacred and profane; for the use of reason to strengthen faith; for conciliation of orthodoxy and free will; and for the intellectual parity of women.

In his letter the bishop interweaves acceptance and rejection of verse writing. He posits that Sor Juana had imitated the “meter” of St. Teresa and St. Gregory of Nazianzus;39 he urges her instead to imitate their religious subject matter. The bishop’s assertion makes no sense, specifically because the two saints are not among the poets who influenced Sor Juana’s masterful use and innovation of metrical and prosodic form, nor does her prose bear any resemblance to St. Teresa’s. Moreover, we may recall that her most important commissions were church-related, the subject matter being utterly religious. In the Answer, Sor Juana refutes this notion of her lack of religious subject matter: first, by emphasizing the intellectual attention she gives to sacred texts; second, by proving that poetry itself can be inherently sacred. In some of her most forceful pages, bringing her defense to a close, she contests her unfitness, as a woman, to write. Indeed, through citation, both St. Gregory and St. Teresa become witnesses for Sor Juana’s side of the argument: Gregory putting forth the view that toleration of one’s enemies is as much a victory as vanquishing them; Teresa as a woman officially authorized to write. Clearly, Juana Inés had decided that if she had to tolerate her enemies, she would at least contest their ignorance and their hypocritical dissimulations. At the end of her reply she essentially unveils “Sor Filotea,” fully acknowledging the difference in status between her and the bishop: “For in addressing you, my sister, as a nun of the veil, I have forgotten the distance between myself and your most distinguished person, which should not occur were I to see you unveiled” (par. 45).

The Answer as Self-Defense. Sor Juana’s Answer, then, was a wise refutation of supposed “offenses.” In setting up her self-defense, Sor Juana kept the potentially hazardous Inquisition in mind.40 While it is not known how much real cause she had to fear being called for questioning, nor how directly she had been threatened with such an action, the Holy Office is a presence mentioned four times in the Answer. First, in a (semi-?)jest: sins against art are not punished by that institution (par. 5). Second, she wants no trouble—literally, “noise”—with the Holy Office (par. 5). Here, we speculate, she might have continued the sentence with “such as Vieira had.” Certainly this is one of the many places where contemporary readers knew more than we; some of them were aware of the Portuguese preacher’s difficulties.41 Later, she implicitly mocks anyone who would suggest that learning is a matter for the Inquisition by mentioning the “very saintly and simple mother superior” who thought so (par. 26). Finally, she issues a brave challenge: if she has been heretical in her theological refutation (the “Letter Worthy of Athena”), as someone has anonymously asserted, then let that nameless coward officially denounce her (par. 40). She is careful to delegitimize vague threats and ill-phrased opinion; from the onset she makes clear her assumption that expressions of opinion, praise or opprobrium, and the pursuit of art itself are immune from punishment.

One aspect of Sor Juana’s legal argumentation would certainly serve as a defense in any future danger. Carefully, she places responsibility for publication of the “Letter Worthy of Athena” on the shoulders of the bishop—whether or not we are to believe, as she claims, that her writing down and sending the originally oral refutation was purely an act of obedience. Two other claims about the “Letter Worthy of Athena” are salient and doubly contradictory: she feels, so she declares, both deceived and elated about its publication; she would have both aborted and corrected it had she known it was going to press. Unable to pass up the chance for wordplay, she here uses the plural “presses,” which referred also to an instrument of torture: things that went to the press could lead to the presses. Sor Juana thus removes responsibility from herself for the printing. Further, she offers the then-standard retraction that would be required in the event her document were to be called in for scrutiny: anything that goes against church teaching is inadvertent and warrants erasure. She said as much in sending the “Letter Worthy of Athena” in the first place, and she reiterates it here in the Answer. While stating firmly the right to hold opinions, as she did in her 1681/82 letter to her confessor, she takes no chances. Interestingly, she employs different tactics in the two letters with respect to being accused. In the earlier, private document of 1681/82, she poses a question and answers it: “Am I perchance a heretic? And if I were, could I become saintly solely through coercion?”42 In the public Answer, she speaks and gives examples of the heresies caused by (male) arrogance, ignorance, and half-knowledge and almost laughs off the suggestion that her writing(s) might be a matter for objection and censorship (pars. 5, 40, 42).

The Answer not only responds to the bishop, it also alerts Sor Juana’s circle of friends to the dangers she faces. In our reading, further, it declares for posterity her own coming silence—implying in advance what that silence might mean. In answering the bishop’s letter, Sor Juana uses the word castigo (chastisement, punishment) insistently. Thus she responds to his stated threat of damnation and to an unstated condemnation, already circulating, that might well have included the spectre of the Inquisition. In the 1681/82 letter of protest, she implicitly declares her intention to continue both cultivating her interest in learning and accepting requests for religious and secular entertainments. In the 1691 letter, she amplifies her arguments and widens the scope of her protest, criticism, and teaching. She performs a sort of counterpreaching, a putting forth of alternative but rational (not mystical) knowledge to the letrados (men of letters). And she tacitly announces a change of course: in the face of both friendly admonition and unfriendly threat, she will again take matters into her own hands (pars. 4, 43). She does not here name what that course is to be. In a striking parallel to some of the studious women who collaborated with St. Jerome in the fourth and fifth centuries and to whom she refers repeatedly in the Answer, Sor Juana may have ended her life as an ascetic.

A Different Worldview, A Different Law: A Woman-Centered Vision

Sor Juana’s worldview was different from ours and different from that of most of her contemporaries. She was intensely aware of women’s participation in the creation of culture and curious to learn of new developments in mechanics and astronomy. Lamenting that there were no women in Mexico City of equal learning and sensibility, she found them in the past, establishing precedents from “a host” of outstanding figures:

…I see a Deborah issuing laws, military as well as political, and governing the people among whom there were so many learned men. I see the exceedingly knowledgeable Queen of Sheba, so learned she dares to test the wisdom of the wisest of all wise men with riddles, without being rebuked for it; indeed, on this very account she is to become judge of the unbelievers. I see so many and such significant women: some adorned with the gift of prophecy, like an Abigail; others, of persuasion, like Esther; others, of piety, like Rahab; others, of perseverance, like Anna [Hannah] the mother of Samuel; and others, infinitely more, with other kinds of qualities and virtues. (par. 30)

Catalogues of illustrious women were a popular literary tradition going back to classical times. While the authors of such lists often pointed out that there were many more figures than could be mentioned, none insisted in the same manner and with the same purpose as Sor Juana that active and creative intelligence in women was not the exception but the rule. To counteract the idea of her own rarity and to support her arguments, Sor Juana emphasized the numbers of women of achievement, representative of many more. While she mentions forty-four women individually, she refers to “so many” (par. 30) “and others, infinitely more” (par. 30), a “vast throng” (par. 31) of which “the books are full” (par. 31). Authors of laws, prayers, predictions, translations, prose, and poetry (itself an expression of divinity) all inspired veneration. Over and over again, she sets herself and classical, biblical, and historical women (Isis, Athena/Minerra, the Virgin Mary, and St. Catherine being the most noteworthy) next to and above male divinities, scholars, rulers, fathers, and husbands.

From a position of hard-earned and fast-fading power, selectively citing patristic erudition, Sor Juana proposed a break with the “law of the fathers” as espoused and imposed by her superiors.43 On many levels, from the most sinful to the most virtuous, the most cowardly to the most brave, the most pagan to the most Christian, Sor Juana draws parallels and situates women next to, above, or in place of men. For instance, men are shown censured as adulterers (par. 43); women are held up as astrologers (par. 31). Teachers are both female and male. She starts and ends with herself as exemplar of the transmutability—rather than the fixity—of the “gendered” attributes of intelligence and learning, as a daughter of St. Jerome and St. Paula:

… I did my best to elevate these studies and direct them to His service, for the goal to which I aspired was the study of Theology. Being a Catholic, I thought it an abject failing not to know everything that can in this life be achieved, through earthly methods, concerning the divine mysteries. And being a nun and not a lay-woman, I thought I should, because I was in religious life, profess the study of letters—the more so as the daughter of such as St. Jerome and St. Paula. For it would be a degeneracy for an idiot daughter to proceed from such learned parents. (par. 10)

Silence Redefined, St. Paul Corrected. “Let women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted them to speak, but to be subject, as also the law saith. But if they would learn anything, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is a shame for a woman to speak in the church” (1 Corinthians 14:34–35). A main argument throughout the Answer demonstrates what Sor Juana considers to be errors committed in applying these words of St. Paul: for centuries authorities had used this biblical dictum to relegate women to silence (pars. 32, 33, 37, 39). Sor Juana exposes the foolishness of the ban and demonstrates the lack of foundation for the imposition of ignorance upon women (pars. 10, 11, 16, 29, 32, 35, 39).44

By its end, Sor Juana’s document declares the likelihood of her future silence, unless she receives support from her former ally, Bishop Fernández: “Unless your instructions intervene, I shall never in my own defense take up the pen again” (par. 43). Therefore, she is careful at the outset to define the meaning of the absence of speech: “I had nearly resolved to leave the matter in silence: yet although silence explains much by the emphasis of leaving all unexplained, because it is a negative thing, one must name the silence, so that what it signifies may be understood” (par. 4). With both seriousness and humor she stresses that, in order to be understood, she must indicate what her silence will say. Playing on saying / not saying and knowing / not knowing, she skirts direct contention with the powers that be and posits alternative “female” viewpoints.45 Throughout, she plumbs another silence, the “silence of treachery”—that of those who did not defend Christ, of those who would not speak up for her.46

Sor Juana inverts and reassigns the usual gender attributions with regard to the issue of silence. As we have remarked, the Answer may imply a decision to silence herself. She was intent when writing it, however, on speech: on proving the sanctity of her lifelong pursuit of knowledge. Even St. Paul, she shows, encouraged desirable silence for both sexes: “And in truth … the ‘Let [them] keep silence’ was meant not only for women, but for all those who are not very competent” (par. 33).

Our reading suggests that at the writing of the Answer, after twenty-five years of public service to crown and cross, Sor Juana was garnering only accusatory and menacing threats. (Here, we agree with interpretations such as those of Dorothy Schons and Dario Puccini.) At this point in her life, she seems to have decided it would be best to follow in the footsteps of her learned foremothers and forefathers—Fabiola (par. 31) or Gregory of Nazianzus (par. 42)—and retreat. But she would not do so before setting the record straight, by belittling antifemale rules and edicts—those of the Council of Trent, for instance—as age-old “prejudice and custom.”47 The established order of gender relations was time-bound and relative, she showed, pointing out that even-older and more venerable traditions and viewpoints, wiser and more sacred laws—those of the “great Author,” as she calls God (par. 12)—supported her thinking.

The Defense of Education for and by Women. Sor Juana argues for the existence of an older and more authoritative source in talking about the dangers for women of not having older women to teach them. Cannily, she speaks as though her audience had already accepted that women should be taught in the first place. To dispel the antagonisms excited by criticism she employs jest (pars. 5, 28, 32). She handles the theme of sex and gender at times through direct exposé, at others, she performs a subtle inversion of the expected double standard regarding the dangers of sexual abuse, the portrayal of eroticism in spiritual literature (considered to be as dangerous for men as for women), the significance of socialization for the patterning of masculine and feminine behavior and dress, and the different status of sexuality in ancient cosmology, in the Bible, and in early Christianity. Here, Jesus Christ is beautiful (par. 19); the Virgin Mary is wise (par. 42). Christ’s beauty is gazed at by a woman (par. 20); a man inscribes, in terms of the human body, the intelligence of a woman (par. 31). Unexplained inversions of grammatical gender in the Bible are remarked upon (par. 38); the kitchen is the scene of philosophical ferment and scientific experiment (par. 28); women, if only to underscore the prohibitions, are imagined at the university and the pulpit (par. 32).

In the Answer, Sor Juana’s strongest statement regarding how nuns should spend their time comes indirectly. Dr. Arce, a noted university professor, had expressed regret that cloistered women were forced to waste their intellect memorizing and repeating—reproducing the past—rather than investigating and applying “scientific principles”:

[Our good Arce] relates that he knew two nuns in this City, one … who had so thoroughly committed to memory the Divine Office, that … she would apply its verses, psalms, and maxims … to all her conversations. The other … was so adept in reading the Epistles of my father St. Jerome … that Arce says: “I thought that I heard Jerome himself, speaking in Spanish.” … [A]nd he grieves that such talents should not have been set to higher studies, guided by principles of science. He never mentions the name of either nun, but he presents them in support of his verdict that the study of sacred letters is not only permissible but most useful and necessary for women, and all the more so for nuns. (par. 41)

Thus, Sor Juana has another authority deplore monastic attitudes about learning. And no wonder: this position directly contradicts what the bishop in his letter held up as desirable.

Reinterpreting “public interests” that have led to the contemporary state of affairs is both Sor Juana’s theme and her practice. She limits her explicit criticism to the stifling mindlessness, to the arrogant and error-ridden policies that are harmful to women. But even the crisis of Mexico City—a crisis brought on by inefficiency and bad government as well as natural disasters—may have been on her mind. Tactically, she speaks from a position of weakness in order to claim a different discursive space—for instance, the spaces where women cook (par. 28) and children play games (par. 27)—and she carries on a conceptual “game” to the end of the Answer, validating what women know and say.

From the beginning of the Answer, as Jean Franco notes, “the transparent fiction of the pseudonym ‘Sor Filotea’ … [permits] an exaggerated deference to the recipient who is supposed to be a powerless woman and thus [exposes] the real power relations behind the egalitarian mask.”48 Under the rhetoric of humility and obedience we read a refusal of her word to those who would keep her voiceless. By the end of the next year, perhaps as a result of a combination of factors, including self-conversion in the face of coercion, disenchantment, and frustration—there are as many interpretations as there are critics—she will turn inward and follow the tradition of the founders of her order. But she has had the last and the lasting word.