Читать книгу The Answer / La Respuesta (Expanded Edition) - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION What Does Sor Juana Mean?

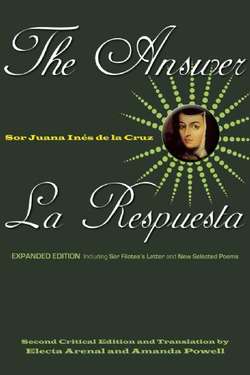

Today scholars and critics in the fields of literature, history, rhetoric, religious studies, women’s and gender studies, queer studies, Latin American studies, colonial/postcolonial discourse, and cultural criticism are researching, presenting, and publishing new studies of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz at a remarkable rate. The year 1995, the tercentenary of her death, marked an exciting increase in the attention paid to this seventeenth-century writer and intellectual. Since then, the range and depth of interest in her work has continued to grow, appropriately mirroring the wide readership she enjoyed in her own lifetime (with nearly twenty editions of her books by the 1690s) and launching the interdisciplinary area of inquiry now referred to as Sor Juana studies—akin to Shakespeare or Cervantes studies. Our second edition of The Answer/ La Respuesta responds to this enhanced interest in a writer whose work illuminates the thought of her world and may throw light on unsettled questions in our own. New perspectives bear on Sor Juana’s “Answer to Sister Filotea,” the essay in which this important author defended her own and, by extension, other women’s learning. As in our first edition, the essay itself appears bilingually, with annotation to clarify its dense web of baroque allusion. We have added in the Appendix a translation of the letter from “Sister Filotea”—who was in reality a powerful bishop—to clarify for readers the opinions and chastisement that prompted Sor Juana’s eloquent statement. Additions to our bibliography give updated printed and online readings on relevant topics.

Sor Juana’s legacy rests ultimately in the beauty, weight, and complexity of her literary art. We have expanded the selection from Sor Juana’s poetry to demonstrate more amply both her lyric prowess and her poetic engagement with the themes of women’s intellectual ability and right to study. Our selection proves Sor Juana’s mastery as a poet and the ever-present inquiry, and frequent spirit of play, that she brought to both creative and studious activity. The introduction to the poems identifies the genres, themes, and strategies of language that make these, from Sor Juana’s hundreds of marvelous poems, particularly fitting to accompany the Answer. In addition, we now include the witty “Prólogo al lector / Prologue to the Reader of These Poems” (from the second collection of her poems published during her lifetime, in 1690), which with offhanded confidence invites us to take or leave what we find. Similarly playful while at the same time critical of misogynist convention is the romance, or ballad, critiquing the admirer who praised Sor Juana by calling her “Phoenix.” In this edition we include this parodic send-up in its entirety. Also newly added are liturgical performance pieces, villancicos dedicated to the Feast of the Assumption that show the Virgin Mary as learned, powerful, and deeply beloved. Finally, love poems in expanded selection here (two more sonnets, and the lavish “Romance decasílabo” or “Ballad in Variant Meter”) explore the nature of love not only as an emotion but also as a field of inquiry.

Sor Juana’s milieu—the seventeenth-century, trans-Atlantic context of so-called Old and New Worlds—was shaped by conflicting redefinitions of political rule, religious mandates, public and private spheres, along with varying views of the natural world and the human soul. This early modern period showed a fascination with hierarchies both celestial and terrestrial and with how these were either to be understood, justified, revered, and upheld or critiqued, challenged, and overthrown. In tune with her era as a learned poet, dramatist, essayist, and theologian, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz at times composed texts to celebrate and affirm institutions, views, or individuals that she deemed worthy of respect. At other times, or simultaneously, she exposed and contradicted those she saw as unjustly or ignorantly holding sway. Gender difference and inequities figured high among the issues that preoccupied both her and her period, and the critical focus that she applied to her culture’s conceptions of female and male abilities and spheres of action can be traced through prose and verse in a range of genres over the two decades of her writing career.

Our twenty-first century is still far from settling questions that Sor Juana posed and explored, whether about gender, sexuality, and identity, or about the relation of religious and spiritual belief to free intellectual inquiry. Today, as in her time, her poetry, drama, and prose command our respect as much for their incisive reasoning as for fluent expression that can be sumptuous or trenchant. To appreciate both these aspects of her texts, the reader must decipher a dense weave of allusion and imagery that characterizes her baroque style, together with the often subtle irony, parody, self-referentiality, and occasionally outrageous humor that characterize both her virtuosity and her overturning of literary conventions. The enigmas of Sor Juana’s biography, however, often take precedence over attention to her challenging and rewarding works themselves. A full reading of these complex texts requires that we identify what Sor Juana’s words meant in her day, even as we explore what they—and she—“mean” for our own context. The Introduction that follows lays out guidelines and pointers for understanding her frequently ironic and elegantly intricate turns of phrase.

Critical Milestones in Sor Juana Studies

Since our first edition of The Answer / La Respuesta (1994), numerous scholars have examined facets of Sor Juana’s life and works in relation to historical, political, cultural, and literary contexts that both facilitated and thwarted her ambitions, skills, and achievements. (See the biographical section, “Juana Ramírez / Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: A Life Without and Within,” in the Introduction.) New interpretations continue to emerge in conferences; monographs; single and collected essays; websites; dramatic productions; and musical, video, and monologic performances that join studies now regarded as classic. Of these many significant studies, we mention a few that we consider essential for those who wish to investigate further the specific issues that this volume addresses.

Time and again we return to the images that many of Sor Juana’s works prompt us to consider: the author, at her writing table, in a book-lined convent cell, pauses deep in thought; or she unstops her inkwell and resolutely plunges into it a quill pen. Frederick Luciani’s Literary Self-Fashioning in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (2004) takes up this theme to trace what he calls the author’s strategies of “self-textualization” as she projects and “personifies” her literary voice. His study traces in her works “self-portraits in the act of writing or reading, the metaphorization of her body and the overall reification of tropes in reference to the self … the mystification and demystification of her poetic calling, self-inscription within gender-bound literary traditions, and meditations on her own literary fame” (16). His study explores various poetic and prose works, including Sor Juana’s Answer to Sor Filotea, identified among her texts as that which conveys the most “detailed and explicit representations of the self” in a demonstration of “the act of reading, analysis, and writing.” For Luciani, The Answer constitutes “both a self-portrait and a performance” (80).

Sor Juana has too long been regarded as an anomaly, an “exceptional woman.” This concept of her does honor to the extraordinary nature of what she accomplished. Yet she herself recognized how this notion is enlisted by a patriarchal culture to “prove the rule” of most women’s lack of ability. We have only to look at her romance 49 (“Apollo help you, as you’re a man!” / Válgate Apolo por hombre! [pp. 190–191, below]), to see how wryly she critiques such isolating and “freakish” views of herself. Scholars are rediscovering how the apparently solitary Mexican writer’s work in fact existed in dialogue with the thinking and writing of other creative women intellectuals, thinkers not only of the ancient biblical and classical periods that she cites in the Answer, but also of her own seventeenth century. Stephanie Merrim’s Early Modern Women’s Writing and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1999) contextualizes Sor Juana by aligning her with several Spanish-, English-, and French-speaking contemporaries who similarly used multiple literary genres to take a strongly pro-female stand in the querelle des femmes, that long debate begun in the Middle Ages on women’s possession or lack of reason and moral virtue—and thus their fitness or unsuitability for education and political rule. Sor Juana stands out for the deftness and variety of her arguments in this tradition, in such texts as the Answer or the poem “Hombres necios” (pp. 164–165, below). As the republication of key texts from the period continues, it becomes increasingly possible to demonstrate points of contact in the thought of early modern women philosophers, theologians, poets, novelists, and dramatists from across Europe, colleagues of Sor Juana, a mapping that more accurately represents the period’s intellectual ferment than does the history we have inherited. As we grow in awareness of how writing circulated in manuscript as well as printed form, we recognize how women maintained vital contacts between courts, noble and bourgeois houses, and convents through travel and correspondence. Thus, we comprehend better how intellectual life was conducted generally and understand how women in particular overcame apparent isolation to engage in central cultural conversations with each other and with male interlocutors.

“Old” Works by Sor Juana in New Light

Some important works, neglected in Sor Juana studies until recently, have come to new attention since our first edition. For example, in 1692–93 Sor Juana wrote the Enigmas ofrecidos a la Casa del Placer (Riddles Offered to the House of Pleasure) at the request of a friend of her patron, the vicereine María Luisa Manrique, who in turn was no doubt doing a favor for a community of aristocratic Portuguese nuns. These twenty rhymed riddles provided opportunities for witty laughter and intellectual challenge during the monastic recreation hour, showing the latitude for nondevotional pastimes in certain cloistered orders of educated and principally upper-class nuns. (These entertainments were, by analogy, the crossword puzzles and sudoko for the privileged of the period.) The answers to these riddles all relate to love: courtly, requited and unrequited, and accompanied by emotions such as longing and jealousy (see Georgina Sabat de Rivers, “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Los Enigmas y sus variaciones”; Jean-Michel Wissmer, Sombras 175–78; and Enigmas translated by Glenna Luschei). Discovered in the 1960s, these texts were omitted from Sor Juana’s Obras completas, and little attention was paid to them prior to 1995. In them, we find enticing traces of Sor Juana’s intellectual and literary correspondence with other learned women of her day. Future archival work may uncover more documents that fill in our picture of these vital connections.

A long-overdue consideration of Sor Juana’s religious writings and spirituality has led to a more nuanced appreciation of her significance not only as a witty baroque poet and rationalist thinker, but also as a theologian. While the values and emphases of a modern secular feminism and its generally nonreligious academic context brought about a recent “boom” in Sor Juana studies, they also worked to occlude some major features of her work—notably, those passages or entire texts that directly engage religious and spiritual topics. Previously, literary and cultural critics tended to overlook these in favor of secular works centered on themes of love, philosophy, or women’s cultural agency. However, in the early modern imperial Spanish territories, Catholic spirituality was central and not secondary to intellectual life. Devotional works constituted an esteemed and a highly popular genre. Scholarly and critical studies now pay more heed to such texts as Sor Juana’s religious drama (sacramental plays, or autos sacramentales), her liturgical villancicos that were set to music and performed as part of church services on feast days, and her lyric poetry on religious themes. In studying the The Devotional Exercises / Los Ejercicios Devotos of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (2005), for example, Grady Wray presents the first annotated, bilingual edition of a text that had remained little known, although the author herself placed it prominently among her achievements. Wray demonstrates that in the Exercises, just as in the Answer and other works, Sor Juana writes from a rich cosmos of classical antiquity, biblical and doctrinal learning, practical scientific exploration, and cultivated wit. The dynamics of gender politics permeates her spirituality, which centers on the Blessed Virgin of the Immaculate Conception: the epitomizing female “Mother of God,” present from the first moment of divine creation, who precedes all other human or natural existence. Thus, as we increasingly see, concerns present in the Answer ring out from other, previously less-regarded works as well.

Commentators long avoided or resisted a direct consideration of the more than forty love poems that Sor Juana addressed to women. Since our first edition, these have come into view as part of a vital cultural practice that produced women’s love poetry to women across sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe and its colonies. Sor Juana directed her poems to the vicereines within the context of an international Sapphic discourse that women writers employed to represent a range of rhetorical modes: tender friendship, playful wooing, and passionate eroticism. Through these poems women demonstrate an active cultural agency, as they rework longstanding poetic vocabularies in order to lay claim to a female authority of learning, wit, engagement, and soul.

The Mystery of Sor Juana’s Last Years

Sor Juana’s sketchily documented final years continue to receive various and conflicting interpretations. Did she voluntarily renounce her lifelong commitment to intellectual activity in favor of devotional practice, or was she obliged to appear to do so by pressures brought to bear by powerful superiors? Did she, despite ecclesiastical censure, manage to maintain a more limited but still-sustaining library? Were her final compositions written with the knowledge of continued support from important figures within her own convent, in Mexico, and in Spain? In delineating likely scenarios for these events, some scholars emphasize her persecution by ecclesiastical authorities, who gained the upper hand when her viceregal patrons returned to Spain. Others point to the fact that Mexico City itself was in a crisis that may have contributed to a shift in priorities on Sor Juana’s part. At the time, corruption and mismanagement led to hoarding; hunger; and a popular uprising, which the government violently suppressed. Some scholars suggest that, bereft of support and surrounded by an atmosphere of panic, and possibly also motivated by inner spiritual convictions that had ripened over time, Sor Juana chose to set aside scholarly study and literary creation for devotional pursuits. However, such a dedication of her time and energies could have been undertaken as an exploration rather than an intentionally final path, with her untimely death intervening to make a provisional choice seem decisive.

In attempting to clarify these questions, we do well to view Sor Juana’s decades-long relationship with her confessor Antonio Núñez de Miranda in more subtle terms than has been customary among critics up to now. Sor Juana’s letter to Núñez (sometimes called her “Spiritual Self-Defense”; see Scott, Madres del Verbo / Mothers of the Word, 53–82) suggests that their relationship was at one time marked by affection and admiration as well as by tension and conflict. He had wanted her to follow the path of Saint Francis in abandonment of worldly concerns; she saw herself closer intellectually to Saint Augustine and to her monastic “father,” Saint Jerome, whose writings displayed classical learning and engagement with as well as detachment from worldly matters. Other models for Sor Juana included her immensely learned contemporary the polymath Jesuit writer Athanasius Kircher, as well as the celebrated Spanish writers, her immediate predecessors, Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca, Gracián, and Góngora. Sor Juana wished for herself, and by extension other qualified women, to be able to pursue any realm of reason and inquiry open to the men of her context: theological disputation; literary creativity; and the sciences, including fields of knowledge new at the time (the physics of sound and vision, for example).

Núñez and Fernández de Santa Cruz, the bishop of Puebla, as well as the openly misogynist archbishop Aguiar y Seijas who did not believe in study for women, however, admonished nuns to conform more strictly to the rules of monastic life than was then the practice in many Mexican convents, where these clerics hoped to carry out stringent reforms. As “Sor Filotea’s” letter insists, women should write, if at all, exclusively on subjects appropriate to their state (see Appendix, pp. 222–223). The male ecclesiastics wished to prevent the spread of interest in “science,” that is, of all secular knowledge, among convent women. The exemplar such clerics held for this limitation of convent achievement to the display of virtue rather than learning was a kidnapped and enslaved woman, Catalina de Jesús, originally from India, whose example of Asian forms of obeisance in a Catholic context (kissing the shoes of ecclesiastics, giving alms, manifesting subservience in all behavior) won their praise. Sor Juana’s friend and literary rival, Carlos Sigüenza y Góngora, wrote that nuns should behave and be considered as angels, inhabitants of a “Paraíso celestial” (Heavenly Paradise), the title of his book on a Mexico City cloister.

In 1995, the historian Elías Trabulse initiated a process, to date unconcluded, of publishing an historical-biographical reinterpretation of the last years of Sor Juana’s life. Earlier views represented her either as voluntarily entering a period of sacrifice and reflection in response to inner conviction or as having been forced into silence and defeated abandonment of her former activities by church authorities. Trabulse’s work sparked heated controversy. How did Sor Juana spend those years, and to what extent did she retreat from intellectual activity? Trabulse has suggested that she found ways to continue her intellectual pursuits despite her outward compliance with a penance imposed upon her. He further points out that an affirmation of faith in Catholic doctrine, published after her death by Archbishop Aguiar y Seijas under an epigraph indicating that she had signed it with her own blood on the occasion of giving up scholarship and writing, in fact, mentions nothing about study. (The document is found in Obras completas, vol. 4, 518–19.) Since it was published after her death, she could not retract it, which Trabulse implies she might have done had she not succumbed to illness. However, as of this writing, full supporting documentation for these interpretations has yet to be released and various aspects of Trabulse’s propositions have been contested.

Marie-Cécile Bénassy-Berling’s “Actualidad del sorjuanismo: 1994–1999” provides what is, to date, the most complete summary available of this biographical controversy. She describes the situation at the end of Sor Juana’s life as follows:

Es obvio ahora que interviene de modo decisivo la autoridad eclesiástica pero, paralelamente, tenemos la certeza de que, hasta el final, la poeta ha conservado una buena dosis de libertad de criterio, y, sobre todo, una entereza de carácter poco común que manifestaba con mucho tino y destreza. En otros términos, la agresividad del clero es cierta; sin embargo, la capacidad de resistencia de la monja es mayor de la que suponíamos. (It is now clear that the authority of the church steps in decisively, but at the same time we are certain that to the very end the poet preserves a large measure of freedom of opinion and above all, an uncommon strength of character, exercised with superb judgment and skill. In other words, there is certainly aggressiveness from the clergy; however, the nun’s resistance is greater than we had supposed). (278)

Bénassy-Berling reminds us that certain facts should be kept in mind, including that Sor Juana never publicly abjured intellectual activity; and that far from being stripped of worldly means, responsibility, or prestige, she, in fact, maintained to the end of her life both control over her personal finances and her role as convent accountant, managing copious sums for the community and negotiating with the world beyond its walls. (284) Bénassy-Berling concludes, “Nuestro parecer personal es que lo principal para Sor Juana era expresarse de una vez, llegar a la cumbre de la fama como lo merecía, sucediese luego lo que sucediese” (My personal opinion is that Sor Juana’s chief objective was to express herself clearly once and for all, and to reach the height of the fame as she deserved, whatever the outcome might be). In other words, Sor Juana seems to have chosen, in the Answer and the subsequent villancicos dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria (excerpted in our Selected Poems section), to express herself brilliantly and boldly on the topic of her own and other women’s learning—pulling out all the stops in these late works. Subsequently, the writer may have had recourse to some subterfuge, seen as necessary for self-preservation, or as Bénassy-Berling puts it, “las maniobras de defensa personal en que era muy perita, incluso encontrando su salvación en una mentira de que no era responsable” (maneuvers for self-defense, at which she was so adept, including finding her salvation in a lie for which she was not responsible). (286) It is conceivable that she may have sought safety from further institutional censure, by appearing to conform to a model of sanctity that was in any case imposed on her. In sum: if the Answer forecasts a decision to silence herself, it seems at least equally to protest in advance the imposition of her silence.

We await further scholarship to make a thorough assessment of these or other speculative versions of the end of Sor Juana’s life. They stand as a potent reminder that we do not yet know, if we ever shall, precisely what transpired in her last years. It seems likely that she sought means to continue on her life’s path, which for decades had involved a thoughtful balancing of intellectual, literary, devotional, and community pursuits, with as much integrity as possible. For example, it is notable that her Enigmas were produced in the framework of communication with the convent community in Lisbon in 1692, after she wrote the Answer—that is, when she had embarked on her purported silence. We hope that more will be revealed through archival investigation and publication. For now, it is rash to take any one version or explication as definitive—whether the haloed saint described by turn-of-the-eighteenth-century Jesuit writer Diego Calleja; the victim of ecclesiastical imposition shown by the early twentieth-century Dorothy Schons; the target of a KGB-like conspiracy indicated by the mid-twentieth-century Octavio Paz; or the cool investor, hoping to weather a difficult time, indicated by Trabulse. The early view, on the one hand, of a rapt Sor Juana “flying” to sanctity or, on the other, that of the exhausted target of ecclesiastical persecution stooping in defeat, seem to hold persistent imaginative sway—and as it happens, these follow timeworn cultural paradigms of women as either pure vessels or fragile victims. Scholars have an obligation to consider all that the known facts do and do not make clear. Nina Scott, surveying “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Three Hundred Years of Controversy and Counting,” (see Bibliography to the Second Edition) wisely suggests that the best course to take in interpreting the poet’s last years is to offer these various hypotheses, allowing readers to speculate and arrive at their own conclusions. In this volume, you hold a sample of what counts most: the invention, intelligence, and achievement of Sor Juana’s writing itself.