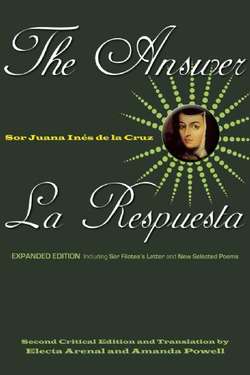

Читать книгу The Answer / La Respuesta (Expanded Edition) - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

Few documents of the seventeenth century embrace matters of learning, intellectual freedom, and power with such erudition and eloquence as does the Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (1691) by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.1 No other treats these concepts so clearly through the lens of gender. A fundamental work in Western feminism, the Respuesta (or Answer to Sor Filotea de la Cruz) stands as a link between Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1403–04) and Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Christine de Pizan’s fifteenth-century French City of Ladies initiated a long tradition of women’s “answers” to their male literary attackers; Wollstonecraft’s eighteenth-century treatise in English envisioned women’s free and equal participation in a world based on reason. Bridging medieval allegory and early modern rationalism, Sor Juana’s seventeenth-century essay in Spanish defended women’s right to develop and use their minds. The document became known early in the twentieth century as a declaration of the intellectual emancipation of women of the Americas.2 Sor Juana’s intellectually and literarily active life challenged the social, cultural, and religious mores that kept women physically and mentally confined. At issue for Sor Juana in 1691, when she wrote the Answer, was whether she would be made to conform to the rules she had embraced upon taking the veil. For more than two decades, as an illustrious exception, she had led a studious and creative existence akin to that of only a few of the most privileged minds of her epoch. In 1691, the church hierarchy wished to impose on her its narrow concept of womanhood, especially religious womanhood. If not her life, certainly her way of life was at stake.

The translation that follows is the first English version of the Respuesta to focus, as Sor Juana does in the original, on gender. A major objective is to do justice, by means of our introduction, annotations, and the translation itself, to its complexity of thought. The Respuesta is not an easy text; Sor Juana’s ambiguities are essential to her intent. In all her poetry and prose—and never more so than in the Respuesta—Sor Juana plays with the many resources of language beyond denotation. Furthermore, her intricacies nearly always have political meanings. That is, she situates her wordplay and its subversions within institutional as well as intellectual structures of power. Like all religious writers of the period (especially women), Sor Juana repeatedly professes her lack of talent and of learning—her intellectual powerlessness. While so doing she in fact displays an erudite negotiation of the central discourses of power of her culture: theology, law, and the forms of classical rhetoric. Always conscious of her gender, she interrogates these forms as she manipulates them, questioning the uses to which such power is put. An outsider by birth, being both female and “illegitimate,” she was drawn inside her culture’s central intellectual concerns—primarily theological—by her “studious inclination.” At the same time, she remained acutely aware of the culture’s exclusions.

Feminism animates the Respuesta. But is that term anachronistic when applied to Sor Juana’s seventeenth-century colonial Mexico? This edition investigates the question by drawing on feminist considerations by a number of scholars, representing varied theoretical and methodological perspectives. Simultaneously, we make use of other historical, theological, biblical, and literary scholarship in the translation itself as well as in the notes and introductory material. The institutional context within which Sor Juana lived, thought, and wrote is itself a difficult “translation” for us; a secular culture does not “read” religious thought and practice with ease or contextual sympathy. Furthermore, Sor Juana wrote from a context of writing women that has been, until recently, buried. In sixteenth and seventeenth-century convents, peninsular and colonial women from a wide range of class backgrounds wrote prose and verse in many forms. These include the narraciones de espíritu (spiritual narrations) and vidas (Lives) that were scrutinized for signs of grace or temptation, plays for performance in the convent, poems, and letters.3 Knowledge of these religious and literary activities, present to Sor Juana, has enriched the translation and our accompanying discussion. While “feminism” has its current meanings within a context of twentieth-century women’s movements for equality and liberation, a “woman question” debate raged in Europe through the medieval and early modern period. Sor Juana consciously entered this controversy. Because she wrote as a woman aware of her gender status and because she intended her arguments to be applied on behalf of other women as women, she is certainly a participant in world-views and activities we call feminist.

Other translations of the Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz exist in English; this one differs by more fully drawing in and upon the spiritual, cultural, social, and female context in which the author lived and wrote her Answer, and to which she refers in the text. Sor Juana’s politics (especially her positioning of herself in relation to her religious superior, Bishop Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz) and her philosophical and theological reasoning (peculiarly her own, because she writes as a woman always attuned to gender) enter the language of the Respuesta—its vocabulary, grammar, and connotative meanings. A translation must be aware enough to render, as Sor Juana did, her problematic stance as an outsider and to capture the resources that she rallied in order to bring the outside in. To preserve Sor Juana’s meaningful ambiguities intact, her translator must know the contexts on which they play and must keep that play between text and contexts in the translated version. To do otherwise mistranslates the author’s multiplicities into a fixity.

There may be dangers, however, in lifting a major figure from one culture to long-overdue prominence in another. One hazard for a writer thus brought to view, especially if she is a woman, may be the acquisition of a symbolic aura that blinds us to her greatness as an artist. In her day, Sor Juana awed her contemporaries with her poetic and intellectual gifts, although at times their praise appeared in patronizing language. Even her continuing status as a kind of icon (her image graces the 200-peso note in Mexico) has not saved much of her work from neglect. Contemporary attention to her feminism, especially as expressed in the famous prose self-defense translated here, may underscore central aspects of her work only to marginalize others. Historically and linguistically, Sor Juana stands at a great remove from modern English-speaking readers. In highlighting her outstanding prose work, it is important that we not forget her prodigious creativity as a poet.

Our edition begins with an introduction aimed to help the general reader approach this major figure of Hispanic letters and to illuminate for all readers essential aspects of Sor Juana’s feminist importance, particularly as reflected in the Answer. We include an index and a substantial selected bibliography to facilitate further study. In the bibliography some present-day editions of Sor Juana’s writings are listed first, followed by the earliest printings in Spain. Then we list some of the most widely distributed translations of her work, studies in Spanish particularly influential in our readings of Sor Juana, Sor Juana criticism in English, and other works we have consulted.

Information on Sor Juana’s life and works is presented in the first section of the two-part introductory essay. The second section, “La Respuesta/The Answer: A Reading” serves as a guide through the rewarding complexities of this document. The text itself follows, in both Spanish and English, with accompanying notes. The annotations clarify particular points and refer both to Sor Juana’s sources and to other scholars’ reflections on the work. Finally, a sampling of poems in Spanish and in English translation offers a sense of the poet’s literary power and the woman-centered vision that inspired it.

1 The author’s dates are 1648 (or, by her account, 1651) to 1695. “Sor” means “sister”; she is known by her convent name.

2 Dorothy Schons was the first to coin this oft-repeated characterization. See Schons, “The First Feminist in the New World” (1925). In 1974, with public pomp in Mexico, Sor Juana was awarded the title of “First Feminist of America.”

>3 See Arenal and Schlau, Untold Sisters.