Читать книгу And Justice For All - Stephen Ellmann - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Finding his Course

In mid-1956 Arthur Chaskalson began the practice of law. Over the next seven years his life would change profoundly. He would go from being a novice advocate to having an impressive and successful practice, and in the process would find a happy fellowship with the other members of the Bar. He would briefly become a member of a political party, the strongly anti-apartheid Liberal Party, but almost as quickly leave this membership behind; meanwhile he would become involved in non-party, but anti-apartheid, political activity that at least bordered on illegality. Even in the field of law itself, he would approach the limits of what law allowed. Important as these developments were, they were only a part of the transitions Arthur was making. Though he remained primarily a commercial lawyer, he began to take political cases, which would assume growing importance in his life. And he would meet and marry the woman with whom he traversed the rest of his life. His life changed professionally and personally; and the two were inevitably connected.

Arthur may have begun his career at the Bar as a ‘pupil’ or apprentice. Years later, in a 2009 interview with Adrian Friedman he said that at that time one or two people might have organised pupillage for themselves, but it was an absolute rarity. But the minutes of a Johannesburg Bar Council meeting on 19 April 1956 include the following:

APPLICATION BY CHASKALSON TO BE A PUPIL

The Chairman reported that Chaskalson had been to see him to ask whether it would be in order for him to do devilling before he is admitted to the Bar.

It was agreed that the Secretary should inform Chaskalson that if he is prepared to pay a fee of £25 he may become a pupil of a junior member of the Johannesburg Bar.

It seems that Arthur was himself one of the rare new advocates of that period who organised pupillages for themselves. But it is also possible that in the end he chose not to pay the fee of £25, and instead simply began his practice.

At any rate he was permitted to join the Bar in 1956 and did so. He joined the group of advocates that came to be known as Group 621. At the time, Johannesburg advocates had their chambers in His Majesty’s Building, but the Bar moved to another building, Innes Chambers, in 1961,1 and Arthur’s recollection is that the group took its name from its location on the sixth floor of Innes Chambers. Group 621 was one of the most prestigious groups, and included a number of leading members of the Bar. These included Bram Fischer, a more senior advocate with whom Arthur would become very close; Fischer, who made his Communist political convictions clear, was also a beloved and respected leader of the Johannesburg Bar. Another member of the group was Sydney Kentridge, not as senior as Bram but already recognised for his exceptional ability; he too would do distinguished work in political cases against the government, and he and Arthur would be friends and colleagues for decades. The fact that Arthur was able to join this distinguished company must have indicated that reports of him from Wits and from his articles of clerkship were very positive.

Arthur did well at the Bar from the first. Not everyone shared his good fortune; new advocates had to wait for attorneys to bring them briefs. Fanie Cilliers, a friend of Arthur’s at the Bar for many years, recalled, ‘The rank junior’s group fees were about R35 per month, and a day in the magistrates’ court would earn him R12.50’2 – so that a young advocate without cases could be in a difficult position indeed. Browde and Selvan, in their ‘largely anecdotal history’ of the Johannesburg Bar from 1940, write that after World War II ‘conditions got better, but even so, survival at the Bar by a newcomer who did not have independent means or a particular following among litigation attorneys was a struggle’. Advocates without cases, they recall, played cards in chambers, went to the movies, or played ‘occasional games of cricket in interleading chambers in His Majesty’s Building’.3 Arthur’s friend Mark Weinberg remembers playing cards with Joe Slovo; when Slovo went into exile (where he would go on to become the chief of staff of the ANC’s guerrilla forces, Umkhonto we Sizwe), the other card players were dismayed because Slovo was so in debt to them at the time. Weinberg himself left the Bar and returned to the Side Bar as an attorney, before leaving South Africa and ultimately making a successful business career in Britain.

Arthur may well have had ‘independent means’ because of the success of the family’s mattress company, but he also had ‘a particular following among litigation attorneys’. Arthur acknowledged that he had achieved a very good LLB degree, in a class that had been very good, and that he and his colleagues came to the Bar with some sort of reputation as good lawyers – but that doesn’t fully explain his individual success. Joel Joffe remembered that Arthur and their mutual friend Sydney Lipschitz were undoubtedly the two outstanding young advocates of that moment. Because of the focus of his articles of clerkship, he had become an expert in insurance law, and his former supervisor from his articled clerk days, Charlie Johnson, sent him work. Arthur himself remembered getting referrals from a range of other people, including young attorneys with whom he was friendly – these would have included Rusty Rostowsky and perhaps other former members of the Wits tennis group – as well as one of his uncles, who was an attorney. He told Adrian Friedman that he didn’t know how you built up your practice; it just happened. Meanwhile, in his first year at the Bar, as we have seen, he was invited by Professor Ellison Kahn of Wits to write the annual entry on insurance law for the Annual Survey of South African Law. He acknowledged in an interview that he was quite young to receive such a prestigious invitation. He wrote the Annual Survey’s insurance article every year from 1957 to 1971, undoubtedly building his reputation for expertise in this field in the process. Over his first years in practice, the great majority of his reported cases (those in which the matter went to court and was resolved with a judicial opinion that was actually published, a discretionary matter in South Africa at the time) seem to have been quite apolitical – though, as we will see, there were a few striking exceptions.

Among his early cases was one in which Arthur and George Bizos represented the opposing parties. Arthur and George at this stage were friendly acquaintances at the Bar; their lifelong friendship had not yet been sealed. In this case, George’s client claimed that the goods Arthur’s client had supplied him were worthless, and on that ground asserted he was entitled to complete rescission of the contract between them. But the case took some time to go forward, and it occurred to Arthur to have the contractual items counted. The count revealed that George’s client had in fact used some of the supposedly worthless goods, because they were no longer present in inventory. In fact, two successive counts revealed that the client had done so twice.

It’s worth emphasising that Arthur thought that this client’s behaviour was funny. Over the years some people would see Arthur as quite a severe, even intimidating presence – but actually he had a generous and even whimsical sense of humour. Rosemary Block, a friend of the Chaskalsons from the 1960s on, recalled that many of his early briefs were accident cases (no doubt because of his expertise in insurance law). He used to have little cars on his desk so that his clients could show him what had happened. When I think of Arthur with toy cars on his desk in chambers, I think also of many years later, when Adrian Friedman interviewed him for his biography, and the discussion of important issues kept being interrupted by the arrival of the Chaskalsons’ several cats, each of whom had to be welcomed by Arthur to the scene.

He also liked the life of the Bar. Years later he would tell Adrian Friedman that the Bar’s common room ‘was a great centre … a great meeting place’ and that

most people would lunch in the common room very regularly. There might be some who didn’t want to, but most people went to the common room regularly. You could sit at any table, it didn’t matter whether there you were a silk or a junior … There were often mixed tables – silks, juniors, younger juniors and older juniors and it was truly a great place – people would talk, meet and discuss and anybody who had done anything wrong would be up for conversation – your reputation was very public at that time.4

Many advocates shared Arthur’s view of the Bar. Jules Browde SC, another of the leading anti-apartheid lawyers of the day, would write:

That we [advocates] are able to survive the stresses and strains of practice is in large measure attributable to the friendship and fellowship of our colleagues. At the Johannesburg Bar there is a long-standing tradition that any member of the Bar will readily come to the assistance of a colleague who has a problem or difficulty, often setting aside his own urgent concerns to do so. Apart from this, life at the Johannesburg Bar has through the years been made pleasurable by the kindness and cordiality of colleagues.5

Moreover, this fellowship largely transcended politics. Arthur recalled his friend Fanie Cilliers saying to him one day, ‘You are a very dangerous person who should either be the Minister of Justice or in jail!’ When I asked him about this, Cilliers didn’t remember it, but he felt it reflected that politics didn’t much matter within the Bar, which was a truly meritocratic institution where talent was recognised. More than one person has called the Johannesburg Bar of this era, or its common room, the best club in the country – though that compliment, as we will see in a moment, implies a serious critique as well.

The positive view of the Bar was not universally held. Dikgang Moseneke would later write in his autobiography that the Bar in the 1980s ‘was a little more racially tolerable and yet at its core it was an old boys’ club. The cream of the crop was white, male and well pedigreed … They were well heeled financially, they owned their world and they were, by and large, arrogant.’6 Arthur was not arrogant, but he was white, male and well pedigreed, and well heeled financially. He enjoyed the fellowship of the Bar. Many years later, Albie Sachs, in interviews with me, would emphasise that advocates, though colleagues, were capable of playing tricks on each other – within the rules, to be sure – for tactical advantage, and he would recall Arthur, on the Constitutional Court, every so often coming out with a strong laugh in response to some witticism of the competitive-advocate style. Arthur was much more than a comfortable member of the Bar, but he was that as well.

If the fellowship of the Bar to some extent transcended politics, nevertheless the Bar encountered politics. Arthur would recall that ‘The Johannesburg Bar, though part of the white establishment, was, however, never seen as a bastion of apartheid. It retained a concern for the rule of law, protested against some of the worst laws that were passed, supported members who defended those charged with political offences, and was viewed with suspicion by those who ruled the state.’7 Browde and Selvan note that ‘a number of statements were made by the Johannesburg Bar from the year 1951 condemning legislation which it regarded as inimical to the values that the Bar supported’.8 No doubt Arthur, already firm in his opposition to apartheid, supported these efforts. As he began to take political cases, he surely also benefited from the Bar’s commitment to supporting its members when they did such work. He would go on to become a recognised leader of the Bar, serving as a member of the Johannesburg Bar Council from 1967 to 1971 and from 1973 to 1984. He would also, as we will see, rely on the Bar’s support to authorise the departure from conventional rules of practice (specifically, the separation of advocates and attorneys) entailed in the creation of the Legal Resources Centre.

At the same time, it seems fair to say that Arthur’s own engagement in anti-apartheid efforts did not emerge, full-blown, at the moment he was called to the Bar. In 1956, as Arthur was beginning his own practice, so too Duma Nokwe, the first black member of the Bar, was beginning his. Nokwe faced a special problem – it was illegal for him to occupy chambers in the advocates’ building, because that building was in an area restricted to whites. As Browde and Selwan write, George Bizos, a friend of Nokwe’s from law school,

volunteered to share his room with Nokwe and they continued to share chambers from 1956 up to the year 1962. By so doing all concerned including the Bar Council risked prosecution. It is to their credit that the leaders of the Bar and of the eighth floor group [of which Bizos was a part] … were prepared on a question of principle to take that risk. In the event the government avoided a confrontation.9

In fact Bizos and Isie Maisels QC had planned to head off potential opposition from some members of the Bar by having Bizos make his offer to share his chambers with Nokwe when he was actually already doing so. Bizos remained distressed that Nokwe did not also gain access to the Bar’s common room (nor did Ismail Mahomed, when he joined the Bar in 1957).10 But Bizos, who had formed ties with black law students while at Wits, was by now already launched on a career focused on opposing the government. Arthur, it seems, had not yet reached this point.

It would be a mistake, however, to see Arthur as unaffected by the political struggles of this time. We have already encountered Arthur’s participation in Torch Commando events that entailed physical battle against right-wing stone-throwers. It was also in the 1950s, evidently, that Arthur joined a political party for the only time in his life, the Liberal Party. (Though Arthur was also pursued later by rumours that he had at some point become a member of the South African Communist Party, I believe these were unfounded, as I will discuss later.) Since Arthur was a university student in the early and mid-1950s, he would have been a member of the Liberal Party then. Founded in 1953, the Liberal Party was not initially a voice for unqualified racial equality, though in the context of the times Arthur’s joining was certainly an expression of his anti-apartheid views. Over time, the party came to stand for a universal, non-racial franchise, and attempted to build membership among blacks as well as whites, a major step in those days, when no blacks had the right to vote for Parliament, their (qualified) franchise having been taken from them in 1936.

Arthur’s formal membership must have lapsed quite soon after he joined, and long before the Liberal Party disbanded in 1968 – after the National Party government made multiracial political parties unlawful, in a statute egregiously titled the Prohibition of Improper Interference Act 51 of 1968. But his affiliation with the sentiments of the Liberal Party was longer lasting. Arthur’s friend Benjamin Pogrund remembered seeing Arthur and Lorraine at parties of the white liberal social set; Pogrund placed these in the late 1950s, but Arthur and Lorraine did not meet until a little later than that, and so these parties presumably took place in the early 1960s. It seems that, as with tennis – where there was a Marxist tennis group and another, less radical, of which Arthur was a part – so with parties, both social and political: there were, Pogrund recalls, two distinct groups of white leftists, those linked to the Liberal Party and those linked to the Communists.11 Apparently there was ‘fierce antipathy’ between some of these people, despite (or because of) their shared opposition to apartheid.12 Beryl Unterhalter, who was a member of the Liberal Party at the time (and whose husband Jack was vice chairman), similarly remembered Arthur and Lorraine in the 1960s as supporters, but not as active members who would have, for instance, served on committees.13

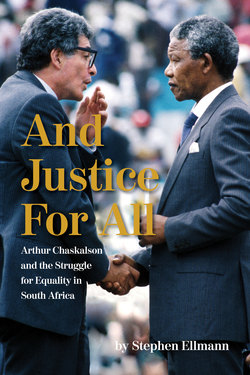

One other political act of Arthur’s stands out from this period. In the early 1960s, after the Sharpeville massacre – a defining moment in South Africa’s history – Nelson Mandela went underground. To get from place to place, he often relied on whites who could lend him their car. Mandela would drive the vehicle, masquerading as a chauffeur ‘driving my master’s car’ to achieve invisibility,14 sometimes or always with the white ‘master’ along. On one occasion, Joe Slovo – who ‘often arranged for drivers and safe places to stay’ for Mandela15 – asked Denis Kuny if he would drive Mandela to a meeting in Ladysmith in Natal. Kuny unhesitatingly agreed. But there was one problem: Kuny’s car wasn’t very reliable. So Kuny went to Arthur and asked if he could borrow his car (a reliable Humber) to transport Nelson Mandela. Arthur unhesitatingly agreed too. Kuny drove Mandela through the night to Ladysmith, dropped him off there, and drove back.

This decision was seriously risky. It was not long after this, in August 1962, that Mandela was apprehended by security forces while engaged in just this sort of drive.16 Denis Kuny told me that if they’d been caught he wouldn’t have disclosed that it was Arthur’s car, but even if he had successfully resisted the ferocious pressures the police could bring to bear, they surely could have identified the car’s owner more prosaically, by tracing its licence plates. Perhaps Arthur could then have persuaded the police that he lent the car without knowing that Mandela was to be driving it, but to do so would have required Arthur to give a false account of events to the police – and he might not have succeeded anyway.

The impression these events give is that Arthur had not yet fully thought through the implications of his commitment against apartheid. He could have joined the Congress of Democrats, a white group aligned with the ‘Congress Alliance’ which the African National Congress led, but he did not. Yet Arthur was willing to fight, in the Torch Commando events, and was willing to risk arrest, in lending his car to Nelson Mandela. His opposition to apartheid and his courage stand out; but he does not yet seem to have evolved a strategy for living a life opposed to apartheid within South Africa. It may also be fair to say that he is still acting in good measure on the basis of personal ties – to his longtime friend Denis Kuny (who for a time shared Arthur’s chambers), or to his brother Sydney, who invited him to the Torch Commando events – rather than on strategic judgement. Perhaps he was even excited by the drama both of participating in the Torch Commando confrontations and of assisting Mandela, the ‘Black Pimpernel’, as he slipped from place to place underground.

But to say that Arthur was still acting out of youth rather than maturity may be quite wrong, because there are additional such moments of which we need to take account. One is an instance in which Arthur and his wife Lorraine sheltered a fugitive in their home. Lorraine told me about this, but she was not sure of the name of the person they had sheltered, and on reflection she pointed out that she may never have known who he was.17 It’s worth emphasising, as well, that this act of sheltering, though clearly covert, may not have been criminal; it is not clear that the fugitive was at the time the subject of any arrest warrant. But it was surely risky. Lorraine acknowledged the risk, but told me that she wasn’t nervous about it; the man needed us, she felt, and so we should help him.

Though Lorraine could not identify the person the Chaskalsons sheltered, it now seems possible to say who this fugitive likely was. As it happens, Roman Eisenstein, a friend of the Chaskalsons from early on (he had got to know Lorraine in her first year at university), recalled visiting the Chaskalsons and met there a man who was never introduced to him. Some months later, Eisenstein encountered the same man in London. He turned out to be Vivian Ezra.18 Lorraine’s tentative recollection that the Chaskalsons might have been asked to shelter this person by Bram Fischer thus seems likely to be correct. Stephen Clingman, Fischer’s biographer, records that after the arrests that led to the Rivonia trial took place in 1963, Fischer realised that Ezra held crucial information that would be jeopardised if he was arrested, and that ‘they had to get Ezra out of the country with all possible speed’.19 It appears that Fischer first asked the Chaskalsons to hide Ezra. Lorraine did not recall where he went next, or how, but Clingman indicates that he made his way secretly out of South Africa.

The second episode of which we need to take account is another story told by Eisenstein, who became a member of the African Resistance Movement (ARM), a group of young white radicals who embarked on a sabotage campaign in the early 1960s. Ultimately he would be sent to prison after a trial in which Arthur appeared on behalf of one or two of Eisenstein’s fellow accused, in 1965. In 1962, another member of ARM, the journalist Yusuf Omar, was caught with a suitcase of explosives. The case against him looked open-andshut. But Omar was out on bail, and Eisenstein arranged for Arthur to come and talk with them. Arthur questioned Omar in what Eisenstein considered the English style – that is, he asked Omar a number of questions but notably did not ask him, ‘Did you do it?’ Then Arthur and the two of them invented a defence for Omar, and Omar told this story to his advocate, George Lowen, who defended the case on this basis. Omar was sentenced to only a year and a half in prison. Subsequently, Eisenstein says, other advocates ‘ragged’ Lowen about Omar’s defence in the advocates’ common room, and Lowen got mad and insisted that the defence was absolutely true.20 As with the harbouring of a fugitive, so in this instance Arthur may not have violated any law; he seems to have carefully avoided knowing, unambiguously and unqualifiedly, that the story he helped Omar devise was false. Still, as in sheltering a fugitive, so here Arthur clearly departed from conventional lawyerly conduct – one does not, ordinarily, assist another lawyer’s client in shaping a defence. Perhaps it was simply the case that when Arthur and Lorraine were asked, they felt obliged to help.

The third episode is a non-political story. Once Arthur was dining in a restaurant in Johannesburg, apparently with another lawyer, when the diners witnessed a homeless man on the street outside the restaurant attack someone with a knife. Arthur jumped up and hurried out of the restaurant and yelled ‘Drop that knife’ at the armed man – who did, in fact, do as he was bid.21 Arthur was brave and determined; and if these three events sound rash from the perspective of four or five decades after the fact, perhaps that is not Arthur’s miscalculation but ours. He and Lorraine would negotiate a delicate course in staying inside South Africa and using South African law against itself over many years, but it may be that he was never entirely strategic and circumspect. When his heart stirred him, at least on several occasions, he acted.

What did he expect the future would bring at this point? One hint is provided by a story told by Arthur’s friend Rusty Rostowsky, who became an attorney in Johannesburg as Arthur was starting out as an advocate. One day in the early 1960s a two- or three-car caravan of lawyers departed on the several hours’ drive from Johannesburg to Swaziland, with Arthur driving one of the cars. The trip had been planned; they were on their way to the Swaziland court, to seek admission to the Swazi legal profession as attorneys. Holding this Swazi credential, they thought, could make it easier for them to emigrate to England, for instance, or Australia than if they could only present themselves as South African lawyers trying to get out of South Africa. (Swaziland became independent in 1968, as Arthur’s son Matthew pointed out to me when I told him this story, so it seems likely that in seeking a Swazi legal credential Arthur and his friends were seeking a British credential as well.) Unfortunately the trip did not go well. For some reason – whether machination or mistake – their motion was not listed on the court’s roll for the day. Arthur stood up and asked the court to hear the motion anyway, but the judge abruptly rejected his request. Nevertheless, the young men did not give up; they drove back to Swaziland a couple of months later and succeeded in getting admitted as attorneys. When Rusty Rostowsky told me this story, I responded that I hadn’t thought that Arthur considered emigration seriously, and Rusty said that that was right – but he did give it enough thought to want to hedge his bets this way. Arthur would never leave South Africa, but at this early moment it seems the thought crossed his mind. Meanwhile, he had already begun the anti-apartheid litigation that would play so large a part in his life over the decades to come.