Читать книгу And Justice For All - Stephen Ellmann - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

And Justice For All: Arthur Chaskalson and the Struggle for Equality in South Africa is a story of the role of law in epochal social change, and of a remarkable life lived in fidelity both to law and to the struggle for social justice. The social change it describes is the victory over apartheid, which captured the imaginations of people all over the world. That victory was won on many fronts and through the efforts of people in many nations, but one of those fronts, and an important one at that, lay in the courts of South Africa itself. Arthur Chaskalson’s story embodies the story of law in the struggle against apartheid. At the same time, his story is not only emblematic but individual, the story of the shaping of the moral intelligence of a lawyer and a judge, not through long inculcation in the values of a stable society but through the fires of a lifetime’s opposition to a society’s injustice. In understanding Arthur Chaskalson, we understand better the roles lawyers can play in social change and the achievement of a just social order, while we see more clearly the interplay of upbringing, experience and character that shapes a person first into a cause lawyer and then into a path-breaking, and foundation-laying, judge.

In telling this story, I am telling the story of a man who was a friend and a mentor to me – and someone whom I admired very much. Readers will find that I appear in this book from time to time, I hope in ways that help to present Arthur’s story rather than diverting attention from it. We met in late 1987, the fall semester in the United States, when we co-taught a seminar on ‘Legal Responses to Apartheid’ at Columbia Law School. This was the second time I had co-taught the course; the first time was also a special opportunity for me, as I worked with Dikgang Moseneke and Sydney and Felicia Kentridge. Teaching with Arthur was exciting and challenging, and so was the trip I made to South Africa at Arthur’s invitation in mid-1988 (Columbia’s summer vacation, South Africa’s mid-winter). Then and on later trips, with Arthur’s help, I got to know some of the outstanding people, many of them lawyers, who were, like Arthur, working within South Africa to challenge the system of apartheid. I had done somewhat similar work as a public interest lawyer at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Alabama – but in Alabama we had a constitution on our side, and did not face the implacable opposition of a reactionary government’s security apparatus. So I understood, broadly, what Arthur and his colleagues were doing, and how hard it was to do, and how important. Those connections long ago, before the end of apartheid, led me to a lifelong scholarly interest in South African law, to lasting ties with a number of South Africans (who also make appearances in this book), and to a friendship with Arthur that continued until he passed away in 2012. I am grateful that his family invited me to tell his story.

This is a South African story, and an important one. The victory of the South African people over apartheid is now receding into memory, or oblivion, as an entire generation of South Africans has been born since the end of that evil regime. What happened in that struggle needs to be remembered. That South African law was part of apartheid is undeniable – and Arthur Chaskalson would have been the last to deny it. That some South African lawyers, Arthur prominent among them, and some South African judges managed to use South African law as a weapon with which to undercut apartheid and to protect clients and litigants in great need is equally important, and gives us a sense – one we should not be quick to surrender – of the potentials of law. Lawyers have been active on behalf of human rights in many unsympathetic settings, and Arthur’s experience offers a striking reminder that these struggles may not be quixotic; instead they may contribute to victory, in the form of short-term courtroom success and long-term national revival.

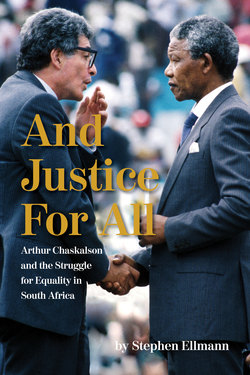

Certainly these efforts by lawyers were far from a substitute for political challenge or the development of a liberation movement, but there was no contradiction between protecting human rights and assisting the anti-apartheid struggle. Many of Arthur’s cases, including his representation of Nelson Mandela in the Rivonia trial of 1963–4, were fought on behalf of leaders of those struggles. Others, notably cases Arthur brought for the Legal Resources Centre, the premier public interest law firm he co-founded in 1978–9 and then led for many years, managed to undercut important legal ‘pillars’ of apartheid, such as the exclusion of blacks from metropolitan areas through ‘influx control’ and the forced removal of black communities from supposedly white areas. At the same time these legal efforts helped keep alive for South Africans living under apartheid the idea of a just rule of law, protecting human rights, an ideal that had never altogether disappeared from view and that might one day prevail. This foundation became the basis for the post-apartheid nation that would – to the world’s surprise – become a reality in 1994. Both constitutional negotiators (among whom Arthur played a prominent role) and then constitutional judges (led by Arthur, as the first President, then the Chief Justice, of the newly created Constitutional Court) devoted themselves to building on it as apartheid ended and democracy began. Despite their efforts, South Africa, having emerged from the long ordeal of apartheid, has found itself infected by a new blight of corruption – but the rule of law, and the institutions protecting it, have been a crucial if incomplete bulwark against this new peril.

This is not only a South African story. In fact, it is part of at least two stories that have echoes around the world. One is the story of the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy in many different nations, and the role that law can play in such transitions. The other is the story of what happens when the happy picture of democratic progress becomes marred. What might have seemed just a few years ago to be a strong and stable democratic consensus in the nations of the West – and a swelling tide of democratisation in other parts of the world as well – does not look so reassuring today. Arthur Chaskalson died in 2012, but before he died he had expanded his focus from South African law to the protection of rights around the world. As the leader of the Eminent Jurists Panel of the International Commission of Jurists, he studied the world’s counterterrorism programmes and found in them frightening evidence of the breakdown of human rights principles in many countries, and in particular in my own country, the United States.

His warnings now seem all too prescient. In the United States, a President with little commitment to many of the rights guarantees that have guided American life for decades is also using his power over judicial appointments to reshape the underlying contours of American law. The United States will not adopt apartheid – that is, a system in which a small racial minority holds almost unlimited sway over a voteless racial majority – but it may well adopt many discriminatory measures, and the country may remain bitterly polarised for decades to come. South African history offers many lessons for Americans and others around the world who are dismayed by such developments, and Arthur’s story in particular offers lessons about the feasibility and the value of legal struggle to protect human rights, struggle that may well take a generation or more to prevail, and then only after many, many disappointments and much suffering.

Arthur’s story speaks to South Africans and to citizens of many other nations, but it is also a powerful human story, telling us about ourselves regardless of nationality or political affiliation. What is it that makes a great judge? That question has two different meanings, and Arthur’s life helps answer it in both those senses. One version of the question is: what are the characteristics of a great judge? Judges often seem inherently conservative, establishment figures, and in countries where law’s work is largely in the ongoing protection of long-recognised values and rules, that appearance may be appropriate and real. But the work of the law can be much more dramatic than that. In South Africa, the post-apartheid judges’ task has been to contribute to the transformation of their country, not a conservative assignment at all. The same can be true in countries whose law seems more settled – as Brown v. Board of Education and many other cases of the modern United States Supreme Court attest. For these decisions, the judges we need must still be judicious; they must even be dispassionate; yet they must be passionately committed to the building of a new world. Arthur was such a judge.

The other version of the question is: what causes a person to develop these characteristics? Or we might put the question more broadly: what causes someone to devote his or her life to seeking the transformation of an unjust society, first as a lawyer and then as a judge – as Arthur did? In another world, I think, Arthur Chaskalson might have become a comfortable member of a legal establishment – but that was not the life he came to lead, and one of the most important tasks of the book will be to trace the roots of his character. Born in 1931, he entered law study as a very smart, quite privileged, white and Jewish young man. He opposed apartheid already, but had not made that position the theme of his life. When Arthur became a co-recipient of the Gruber Justice Prize in 2004, the award said of him that if a life could be mapped, his ‘would surely appear as a straight line starting from a commitment to human rights, and leading, without deviation, to the bench of the Constitutional Court of South Africa and the position of Chief Justice. It is a long line, but an unwavering one.’1 I do not think Arthur ‘wavered’, but I also do not think his life moved along a simple straight line as this image would have it.

As he grew into adulthood, his focus on the injustice around him sharpened. His own father had died when Arthur was a small child; now he became very close to a senior lawyer, Bram Fischer, whose commitment to the fight against apartheid was absolute and self-sacrificing. In 1961, at the age of 30, he married a fiery, 19-year-old woman whom he loved for the rest of his long life. Lorraine Chaskalson was a charismatic English professor, a poet, a lover of art and beauty, mother to the Chaskalsons’ two sons, and Arthur’s moral compass, part of every decision he made as he shaped his life in the years to come. The state grew harsher; Chaskalson bravely resisted, joining his older mentor in representing Nelson Mandela. After Mandela’s trial, he might have chosen to join a political party, above ground or underground, or he might have chosen to leave the country. He did none of these. Instead he remained, practising law, earning a reputation on all sides for formidable integrity. What that meant and what it cost him – how this man of integrity shaped a life in the law when law and justice were so rarely aligned – will also be a central concern of the book.

There is more to be said on all these questions. This book is a biography, rather than a work of social science. I do not propose grand theories of the law, or of human development; instead, I will tell Arthur’s own story in detail and seek to draw from the moments of his life more nuanced, though more individual, answers than broader accounts can generate. Along the way I will also be telling some of South Africa’s story. For readers not familiar with modern South African history, I will try to provide the context that will illuminate the particular moments in Arthur’s life.

But even those who know South African history well may not know the aspects of it that were most salient for Arthur, and so to write this biography I must also be to some extent a historian. The book will look closely at the dramatic events of the Rivonia trial, in which Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment; this trial is well known but I believe that a focus on it from the perspective of the decisions that the accused, including Mandela, and their lawyers, including Arthur, made will still shed new light. Fifteen years later Arthur began building the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), which became in the years before the end of apartheid the leading public interest law group in South Africa; understanding Arthur’s work at the LRC is important in itself but also important for an understanding of this significant institution. Arthur’s next role was in the negotiation of the first post-apartheid Constitution; here, too, much has already been written, but a focus on the particular contribution Arthur made will illuminate what that negotiation process actually was. Perhaps most strikingly, looking at Arthur’s role in the creation and first decade of the Constitutional Court will tell us a lot about the court itself as well as about Arthur. Finally, Arthur’s efforts to publicise and criticise the world’s counter-terrorism programmes, in the years after he left the Constitutional Court in 2005, are an important element of Arthur’s own career, but they turn out to have potentially chilling relevance to the state of world liberty today. The product of all these stories, I hope, will be a picture of the role of law in South Africa’s victory over apartheid, and in the world’s struggles against injustice, and a picture of an extraordinary lawyer, judge and man, Arthur Chaskalson.