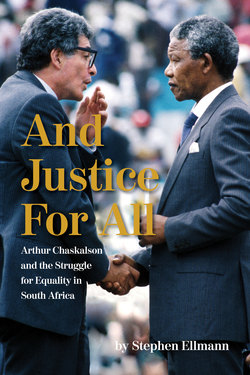

Читать книгу And Justice For All - Stephen Ellmann - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SIX

Rivonia: The Defence Team and its Work

The legal and political world of the 1950s in South Africa was dominated by two battles. One was the struggle over the National Party’s effort to deprive ‘Coloured’ South Africans of their right to representation in Parliament; it took the backing of the South Africa’s highest court to finally decide that issue in the government’s favour. The other was the Treason Trial, a marathon proceeding that lasted five years and tied up much of the ANC in legal defence, even though it rather marvellously ended in a verdict of not guilty.

After these controversies comes the Rivonia trial, the most important South African trial of the 1960s and probably the most important of the last three decades of apartheid, from 1960 to 1993. It sent many of the senior leaders of the ANC, including Nelson Mandela, to prison under sentences of life imprisonment. That was a tremendous defeat. But it did not result in their execution, as it certainly could have. That was a profound victory, one that even the National Party, the party of apartheid, would come to recognise, because without this victory Nelson Mandela would not have lived to negotiate the end of apartheid and become post-apartheid South Africa’s first President.

The Rivonia trial is a tremendously significant case. But precisely because it is so integral to South African legal and political history, it has been the subject of many thoughtful works already. I will not trace the progress of the case witness by witness; Arthur’s friend Joel Joffe wrote that book, The State vs. Nelson Mandela. Nor will I trace all the ramifications of this case among the people whom it affected or ensnared; many of these are illuminated in works such as Glenn Frankel’s Rivonia’s Children and Hilda Bernstein’s The World That Was Ours. Instead, while telling the central story of the case, I will focus on the role Arthur played in it and the impact it had on him – above all, the choices the case required Arthur to make at the line between morality and legality, and the connections it enabled him to establish in relationships that were central to the rest of his life.

In telling the Rivonia story, I am certainly telling Arthur’s story. The lawyers for the Rivonia accused understood that the case marked a critical moment in South African life; that the stakes were extremely high; and that they themselves would be tested at every moment and their performance in that test remembered for the rest of their lives. Arthur was an integral member of the defence team, and of the larger team made up of the lawyers and their clients, the Rivonia accused. The decisions the team made, he was part of and contributed to.

Arthur also made vital individual contributions in the division of labour that the lawyers evolved; in this division, Arthur’s role was not primarily to examine witnesses (though he did some of that) but rather to master the law and the voluminous details of the facts, both to offer argument himself and to guide his colleagues in their work with witnesses. (One of the accused, Denis Goldberg, described Arthur as accomplishing, ‘in the days before computer spreadsheets, the setting out of the comments or the remarks of each witness in relation to each of the accused and each of the allegations against us, as if in a spreadsheet’ – and also mentioned that Arthur ‘grabbed’ Denis’s notes to use as well. All this was essential in part because the defence counsel could not afford to purchase a running transcript of the events in court.1) This work of analysis went on all the time, and culminated for Arthur personally in a prominent role in the team’s closing arguments to the judge. But Arthur will not always stand out in the story. We must understand him as living these extraordinary, even epochal moments, and to understand what he lived I must provide the broad outlines of the Rivonia story as it involved all of these lawyers and clients – and many more besides.

*

To begin at the beginning: Joel Joffe, Arthur’s lifelong friend from their days at Wits, was the attorney for the defence in the Rivonia case. As Joel describes his appointment, Hilda Bernstein, whose husband Rusty had been arrested at the Lilliesleaf farm, in the Rivonia area near Johannesburg, along with Nelson Mandela and others, came to his office first. Her husband and the others had not yet been charged, but instead were being held under 90-day detention, one of the ferocious powers South Africa had recently conferred on its security forces. Since she did not know what would happen to him, she asked Joel to take the case if he was charged. Then, over the following weeks, three more clients came to him. One was Albertina Sisulu, on behalf of her husband Walter, Nelson Mandela’s mentor and a core leader of the ANC, also arrested at Rivonia and in 90-day detention. A second was Annie Goldberg, ‘the frail mother of Denis Goldberg’; Goldberg, an engineer, had also been arrested at Rivonia and placed in detention. The third was Winnie Mandela. Nelson Mandela by this time had already been convicted and imprisoned on Robben Island, but it now appeared he would be charged along with those who had been arrested at Rivonia.2

Notwithstanding Joel Joffe’s account of his appointment, what actually took place was this: the advocates who would appear in the trial in fact chose him as their attorney, and one of them instructed Hilda Bernstein to close the circle by formally retaining Joel. Who were the advocates? Arthur was one, though the first advocate involved in the case would have been Bram Fischer. As Stephen Clingman, Fischer’s biographer, writes, ‘in the lead-up to the Rivonia Trial [Arthur] was once again with Bram in chambers, and offered him any assistance should he need it’.3 Certainly Arthur would have understood, as soon as the arrests at Rivonia took place, that another trial was coming, as momentous as the Treason Trial of the 1950s. He would have assumed, too, that Bram Fischer would very likely become counsel to the accused. Fischer, an eminent lawyer, had been part of the Treason Trial defence team; perhaps more important, he made no effort to hide his left-wing politics and so it was natural to assume that the people facing charges would want his aid.

So Arthur volunteered his services to Bram. Bram and Arthur already respected each other deeply – Bram had told his daughter Ilse in 1960, when they all found themselves in an elevator at chambers together, that Arthur was one of the most brilliant young advocates.4 He would tell one of the Rivonia accused that Arthur was the next Isie Maisels – high praise indeed, for Maisels was a tremendously respected advocate who had also played a central part in the successful Treason Trial defence.5 Arthur’s wife Lorraine recalls that Bram was very fond of Arthur even before the Rivonia trial,6 but Ilse’s sense was that they didn’t know each other that well up to this point. If so, Arthur’s choice to volunteer, and his simultaneous decision to press Bram to take on the case, both suggest that he was acting for much the same reasons as he had expressed years earlier when he was a student at Wits: the question was not what was politic, but what was right. To join this case was also an act of courage, as Bob Hepple (an advocate, and for a time one of the accused) would write, for ‘there is already a large amount of hostile comment against the accused in the media. They [the defence lawyers] will be ostracized by many in the white community, and can expect to be targeted by the police.’7

Bram meanwhile may have chosen George Bizos, whom Arthur had known since their days at Wits. George had had a much more political practice than Arthur since their graduation and on that score was a natural recruit for the case. The fourth advocate on the team was Vernon Berrangé, an ex-Communist, the pre-eminent cross-examiner of his day, and a man who fully expected that taking this case would end his legal career in South Africa.8 So the team consisted of two senior, even eminent, counsel, Fischer and Berrangé, and two much younger lawyers, Arthur and George. Bizos would write later that ‘Arthur and I were comparatively junior members of the Bar, and both of us were anxious about what we and our clients would face’.

As for Joel, it was Arthur who had recommended him to Bram. Bram’s initial response was to say he’d need to think about it, because he didn’t really know Joel, but then Bram came back and said he’d like to meet him. So Arthur arranged a lunch with Joel and Bram, and either at this lunch or afterwards Bram said yes, and they asked Joel if he would serve as the attorney, and Joel said he would if the accused wanted him.9 Or rather, Joel said, they first picked another attorney, Michael Parkington, who had worked in the Treason Trial, but he declined and so they turned to Joel. Joel said that Arthur and his colleagues never told him that he was their second choice, but he learned it years later, through some back channel.10 Second choice or not, Joel agreed to serve, Bram then sent Hilda Bernstein to Joel, and the circle was closed.11

Why didn’t Joel tell the story this way in his book? Joel explained to his interviewer Adrian Friedman that he didn’t want to embarrass Arthur.12 Arthur confirmed this, telling the same interviewer that when Joel wrote his book he didn’t deal with this matter at all; in order to protect Arthur and perhaps others, he left out lots of things.13 There certainly could have been embarrassment, because the advocates had essentially begun their work by undercutting at least the spirit of the rules separating the Bar and the Side Bar. Whether their arrangements directly violated those rules may be debatable, but this too seems likely, because today – when the rigidity of the division between advocates and attorneys has been eased – there remains a rule declaring that ‘Save in exceptional circumstances, it is improper for counsel to recommend a particular attorney or firm of attorneys to lay clients’.14

In this and many other respects too, the lawyers for the accused in the Rivonia trial would find themselves pressed to the limit of their ethical obligations. To lawyers as committed to ethical boundaries as Arthur, these choices were no small matter. They took courage. They required financial sacrifice. They called for trust, between the lawyers and between the lawyers and clients, that no one would disclose the delicate moral choices being made, and so these decisions were part of the creation of deep solidarity among the lawyers and the accused. They also demanded a willingness to parse the rules of ethics and their interaction with what might be called the rules of justice – a combination of close legal reasoning and of weighing strictly legal obligations against more broadly moral duties.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to understand how Joel came to be available to play a role in the Rivonia trial at all. Joel was, when we last saw him, an advocate, joining Arthur in the defence of the Letsoko accused. But he had meanwhile decided to leave South Africa, whose future he had come to despair of. As he was preparing to move to Australia, the law firm of Kantor and Wolpe, where Joel had worked as an attorney at an earlier stage of his career, had fallen into crisis: Harold Wolpe, arrested shortly after the Rivonia raid, had escaped from jail and fled the country, and his partner and brother-in-law Jimmy Kantor, a man with little or no political involvement, had then been arrested too. The firm needed someone to bring its affairs to an end, and Joel agreed to move from the Bar to the Side Bar – in other words, to cease practice as an advocate and instead become an attorney – for this purpose. Arthur, describing this decision, said that Joel had ‘saintly qualities’ – an echo of what had once been said about Bram Fischer by a witness against him when Bram, after the Rivonia case, became a criminal accused himself.15 And Arthur facilitated the transition, which might have required a six-month cleansing period, by finding a precedent in special circumstances after the Anglo-Boer War when the six-month rule hadn’t been enforced, and so Joel was able to make this transition. In fact, as late as August 1963, Joel was still serving as an advocate alongside Arthur in the Letsoko case. Hilda Bernstein would come to his office in September to retain him as the attorney for the Rivonia trial.16

Bram Fischer himself did not agree at once to do the case. He may have hoped to pass that cup to Berrangé.17 But Arthur argued quite strongly that Bram should be involved.18 Why was Bram reluctant? Because he was himself implicated, deeply, in the underground conspiracy that had operated out of the farm in Rivonia. At the time, however, his colleagues didn’t know that. Arthur told his interviewer that none of them knew Bram was as deeply involved as he was, or at any rate Arthur himself didn’t and he was pretty sure George and Joel didn’t – though they knew Fischer was involved and assumed he had some contact with the accused as his political associates. George Bizos writes, similarly, that when the lawyers came together, ‘none of us knew the extent of Bram’s involvement in the underground movement or that this was the cause of his hesitation’.19

Arthur and his colleagues would gradually learn more of how deeply Bram was involved. Arthur recalled that midway through the trial they were working through the documentary evidence in the case, and came across one or two quite incriminating documents in Bram’s handwriting. Adrian Friedman asked Arthur what he did then; Arthur answered that he kept reading. Meanwhile he told Bram. How did Bram react? Apparently he didn’t say much, but Arthur said, ‘I told him what was there. So at that stage I knew that.’ Earlier, when the lawyers and clients had got together for the first time – most of the clients had been in 90-day detention without trial, out of their lawyers’ reach, while Nelson Mandela was already in prison on Robben Island for an earlier conviction – Arthur recalled that Rusty Bernstein, who had a good sense of Bram’s actual involvement, said that Bram ‘should get the Victoria Cross’. Arthur acknowledged that he didn’t realise the full implications of what Bernstein was saying at the time, but he understood that Bram was very vulnerable as a general matter.20

During the trial the noose was slowly tightened, though never to the point of actually arresting Bram – that would come later. The trial began with the testimony of several African witnesses who had been employed at the Rivonia site; any of them could potentially have identified Bram himself as one of the people they had seen there. With this in mind, Bram chose to be absent during the first week of trial – leaving the cross-examination to the youngest members of the team, George and Arthur. George recalls that one focus of their cross-examination was the fact that these witnesses had been held in detention without trial.21 Arthur’s cross-examination of one of these witnesses, a man named Joseph Mashifane, revealed a number of problems in Mashifane’s identification of Rusty Bernstein as having participated in setting up a radio antenna for a clandestine ANC broadcast – and the undercutting of this claim quite likely played a part in Bernstein’s ultimate acquittal.22 It is worth adding that Arthur begins his cross-examination of Mashifane by addressing him as ‘Joseph’. Perhaps that was a tactical choice, but it indicates at least that even for dedicated anti-apartheid lawyers in 1963, it was acceptable to address an African witness by his or her first name. Over time, the Rivonia lawyers would develop a profound respect for their clients – but at least at the beginning this respect was shaded by the condescending traditions of South African race relations.

How well did Arthur understand the situation Bram faced? Arthur recalled that he never spoke to Bram about the problem posed by these early witnesses, but he pointed out years later that the defence had actually sought a postponement that would have enabled Bram to return in time for these witnesses. Moreover, the defence rarely knew when any given witness would be called, so Bram could not avoid facing the risk of encountering a witness who would identify him (though none ever did).23

The tension did not abate. Later in the trial, the prosecution presented a particular document which a handwriting expert testified was written by Wolpe. The prosecutor passed this document to Bram, who looked at it without reaction and passed it to George Bizos, who looked at it and passed it to Joel – who saw that the handwriting was in fact Bram’s. Joel says that Arthur too must have been there for this moment.24 At another point, the prosecutor seemed to go far out of his way ‘to implicate Bram and associate him with the Communist Party’. As George Bizos recalls, the prosecutor presented in court an article in which Rusty Bernstein, one of the accused, had praised Bram ten years previously. The article had no relevance to the charges the accused faced.

Yet suddenly, and apropos of nothing in particular, Yutar [the prosecutor] pounced:

YUTAR: Who was the secretary general of the Communist Party?

BERNSTEIN: I am not prepared to answer that question.

YUTAR: Well, since you are unable to answer that question, perhaps we may conclude that it was the gentleman referred to in the exhibit before you. Will you please hand it to the judge?25

This was playing dirty, presumably to send a message to Bram.26 For now, as his biographer writes, Bram was relatively safe – the government apparently did not want to face the negative publicity that an arrest of the lead defence counsel in this controversial trial would have generated.27 But after the Rivonia trial ended, Bram would in due course be arrested, tried, and sent to prison, and he would die as a prisoner.

Only one step remained to put the defence team in place: a way to pay the lawyers’ fees. None of the lawyers charged their full fee; Joel recalled that they worked for a tenth or a quarter of their normal charges, presumably depending on their personal circumstances.28 Arthur remembered exactly what he charged: R2,000, or approximately $2,800 for the work of close to a year. His interviewer, Adrian Friedman, asked him how this compared with what he would have charged for regular cases, and Arthur made it clear there was simply no comparison at all, but that he ‘had enough money to manage’.29 But even so, the money was a problem. ‘There was only one person to turn to for funds and that was Canon John Collins of St Paul’s Cathedral, London’, who had created the International Defence and Aid Fund during the Treason Trial at the instigation of the Bishop of Johannesburg.30 Collins supplied some £19,500, on which the entire case was run. Interestingly, he seems to have raised even more – organising an art auction at Christie’s that netted £36,000.31 Perhaps some of what remained was used to cover the living expenses of the families of the accused; Defence and Aid sought to support both trials and families of the trialists.

But even with the advocates working for heavily discounted fees, the budget was still not enough for the lawyers to purchase a full trial transcript. George Bizos similarly recalls that the funding they had was not enough to cover their travel expenses.32 Fischer’s biographer indicates that Bram himself, ‘besides leading the defence, was also arranging for its funding, writing innumerable letters overseas: this was a small team for such a big trial, though they were being paid the lawyer’s equivalent of a pittance’.33 Evidently there was particular concern not to run foul of a rule of legal ethics. Joel Joffe recalled: ‘There was a Bar rule that Counsel must be paid within three months, and if they weren’t, the attorney could not brief another advocate. The Bar was tougher than a trade union. At one point, with money running out, we had to ask Bram to move quickly. It arrived just in time.’34 It seems possible, however, that as with the formation of the legal team (advocates first, attorney second, in contravention of the normal approach), so here the team’s adherence to the rules may have been more a matter of form than of spirit. It is even conceivable that a letter invoking this Bar rule might have been helpful in extracting the promised funds from Defence and Aid, which faced many demands on its resources.

*

The Rivonia accused were on trial for their lives. The charge was sabotage, a charge that didn’t quite carry the ring of treason but still carried the death penalty and was, moreover, in a number of ways easier for the prosecution to prove. And the nine accused – Rusty Bernstein, Denis Goldberg, Ahmed Kathrada, Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Elias Motsoaledi and Walter Sisulu, plus Jimmy Kantor, the lawyer who had been swept up in the case after his law partner, Harold Wolpe, escaped from jail and fled the country35 – included some of the most senior ANC figures.36 The lives of the movement’s leaders were literally at stake.

Obviously this posed a profound tactical problem. But it was not simply a problem of surviving the trial. Instead, the Rivonia accused and their lawyers also faced at least two other legal challenges. The accused (or at any rate the most senior of them) were guilty as charged, and they faced a prosecution newly energised to pursue its case against them not just with determination but with disregard for the rules that had long bound South African prosecutors. At the same time the accused imposed their own limitations: they would not defend themselves legally at the cost of harm to their political cause; and they needed to shape their strategy through consultation with lawyers to whom they were positively disposed, but with whom they were not actually well acquainted. Each of these aspects of the development of the defence strategy will emerge more fully in the following account.

As for the more strictly legal challenges, on the issue of their own guilt the ANC had decided that non-violence no longer could sustain their struggle against apartheid, and Rivonia had become the base for Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, the ‘Spear of the Nation’), the ANC’s military wing. Mandela himself had been the head of MK until his earlier arrest and conviction.

Moreover, the accused faced a further problem, which was that the state had put its full force, or almost its full force – matters would grow even worse in the years to come – into building the case against them. Ordinary witnesses were held in 90-day detention without trial though they were accused of no crime, and the coercive force of this kind of solitary confinement was now becoming apparent. While much of the testimony the security police elicited was more or less accurate, the police did not hesitate to press witnesses further and to manufacture evidence when it suited their interests. This was a new era of dirty tactics. As Hilda Bernstein wrote, ‘The State is revealing for the first time the extent to which it will go, that it will stop at nothing, neither in forcing testimony from witnesses under duress, in the suborning of false evidence, nor in the coaching of witnesses.’37 Her husband Rusty agrees: ‘The Rivonia Trial seems to mark the point of transition from the law as it was to the law as apartheid has deformed it’ – though he maintains that the judge, Quartus de Wet, tried, despite ‘all the inbuilt white South African prejudices and certainties about blacks’, to ‘hang on to the traditional South African legal style in a society where justice has already been sacrificed on the altar of “security”’.38 In any event, those tactics were effective.

How could these problems be solved? Perhaps the most important part of answering that question was answering another: who would be doing the problem-solving? Much traditional lawyering takes for granted that the lawyer will decide most aspects of the course of action to be pursued on the client’s behalf, but that was not what happened in the Rivonia case. Joel Joffe’s account makes it clear that the lawyers gradually came to understand the broad strategy that the clients had developed, and then followed those instructions.

But the first step was for the lawyers and clients to meet. Some of them knew each other very well. Bram, a leader of the underground Communist Party, was a political comrade of the accused. Berrangé would have known at least some of the accused from his work in the Treason Trial. George Bizos, with his heavy political caseload, knew most of them. But Arthur and Joel did not.

Denis Goldberg, one of the accused, remembered that George also helped facilitate their meetings, ‘adding a note of splendid gentility to consultations in an office in the prison’ by bringing ‘packets of Vienna sausages, gherkins and sweetmeats’.39 George’s recollection is that he and Joel brought ‘home-grown salad, fruit, cheese, cold cuts and loaves of French bread’.40

This first day was also a day when what the accused had already endured, in prison or in 90-day detention in jail, became evident. Joffe wrote of Nelson Mandela that ‘his face, formerly well filled out and a rounded, deep-glistening brown, was now hollow-cheeked, a sickly pale, yellowish colour. The skin hung in bags under his eyes. His manner, however, was the same: friendly, easy going, jovial, confident.’ Among the others, Joffe wrote that ‘On the first day [Rusty Bernstein] struck me as the one most obviously affected by his detention. He seemed depressed, listless and nervous.’ At least two of the others, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni, had been assaulted or tortured while in detention, as they would later declare in open court.41

Lawyers and clients needed to get to know each other. At this first meeting, in fact, the lawyers did not even know who would be brought to them as their clients.42 Mandela in particular was a surprise; after all, he was already in prison when the police raided Rivonia. Unfortunately, his comrades had held onto many incriminating documents – apparently for the sake of history. (Arthur drew from this the lesson that documents should be destroyed whenever possible, a practice he followed in his own life.) Arthur remembered Mandela’s arrival, wearing, in midwinter, the shorts and sandals that were the South African prison uniform for black prisoners. All of the clients, Arthur saw, regarded Mandela as their leader. Everything was always done in consultation – everyone talked as decisions were made – but Mandela was very important to the process. If decisions had to be communicated to the lawyers, Mandela would do it.43

Undoubtedly Arthur and Joel, lawyers with relatively little grounding in South African black politics and relatively little personal experience in close relationships with black people, were deeply impressed by the ANC leaders they were now meeting. Glenn Frankel, based on an interview with Joel, writes:

Joffe had never had black friends growing up. Despite his attempt to treat Africans as equals, he had always harboured the sense that they were somehow inferior. It was something bred into him since childhood. To be among blacks who were truly great men – wise, considerate, caring – was a great revelation. Yet in some ways it increased his burden. These men were more than clients, more even than friends, Joffe felt. They were a national treasure he had been entrusted to protect and defend.44

Joel himself illustrates the transformation he experienced. Telling the story of Hilda Bernstein’s first visit to his office, he mentions that he warned her that

‘public opinion is so heavily against your husband and the others that in the end this is likely to count heavily.’ She looked at me in amazement. ‘Public opinion,’ she said. ‘Public opinion, against the Rivonia prisoners?’ I looked at her, surprised. Was it possible that anyone intelligent, adult, literate and living in South Africa could doubt that the stream of public opinion was running heavily against the Rivonia accused? She looked at me again and said, ‘Mr Joffe, I think we speak a different language. You’re talking of white public opinion. I am talking of majority public opinion, which is not against, but for the Rivonia accused.’

Joel writes: ‘It is so easy to go astray in South Africa.’45 Arthur and Joel were not identical, of course, but they came from a similar background, and it is not hard to infer that Arthur too felt this kind of illumination as he came to know the Rivonia clients.

For their part, their clients – as Arthur recalls – accepted that these young lawyers were there and would do their best for them. But it’s possible to discern the uneasiness the clients must have felt in the words of Hilda Bernstein, who wrote that ‘Arthur Chaskalson was also a young man. He had made a reputation for himself at the Johannesburg Bar by his brilliant mind, attractive personality and easy manner’ – generous praise, but noting Arthur’s youth and tacitly acknowledging his relatively non-political approach to his work up till then.46 Her husband Rusty, one of the accused, similarly wrote of Arthur, ‘whom most of us are meeting for the first time’, that ‘Bram recommends him as a brilliant young barrister who is prepared to risk a lucrative career in commercial and insurance law to take a case against the tide of public opinion. It proves to be an inspired choice,’ and Joel ‘an equally inspired’ one.47

Lawyers and clients began to meet. Of course they met inside the prison, and they took for granted that their meetings were under surveillance. To counter this, they devised ways of communicating discreetly, for example by writing down, but never speaking, the name of someone they are discussing, and then burning the revealing pieces of paper before leaving the meeting. (Fortunately, they were allowed to smoke.) On one occasion, the police officer Swanepoel, who as we have seen had already crossed Arthur’s path, was vigilantly observing a meeting of the accused. One of them, Govan Mbeki, carefully wrote a note and passed it to Mandela, who judiciously read it and passed it along. Swanepoel couldn’t resist any longer, and burst into the room to confiscate this revealing piece of paper before it was burned. Mandela recalled that its message read, in block capitals, ‘ISN’T SWANEPOEL A FINE-LOOKING CHAP?’ But memories have faded and it is possible Mbeki wrote, instead, ‘“It’s so nice to have Lieutenant Swanepoel with us again,” (deliberately downgrading the captain’s rank).’48

More seriously, they confronted the question of how to defend the case. The lawyers had warned the accused from the start that they faced potential death penalties – although, for reasons that remain obscure, the state never explicitly asked for this sentence. The accused, for their part, believed that death sentences were likely; Nelson Mandela writes that ‘from the start, we considered it [the death penalty] the most likely outcome of the trial’.49 But there were nine people accused; inevitably the evidence against some was stronger than that against others. ‘On the other hand,’ Joffe writes, ‘there was the overall consideration – which to the accused seemed to be the most important – that of establishing the true facts of the movements in which they had been engaged and their true aims as distinct from the gross distortions presented by the prosecution’.50 As Joffe elaborates:

None of [the accused] were prepared to deny associations with the bodies to which they had belonged; those who had been associated with the African National Congress would under no circumstances deny the fact, nor would those who had been associated with the Communist Party, or Umkhonto we Sizwe. In their eyes, they made clear, this was less a trial in law than a confrontation in politics … They would be speaking in court as … almost the gladiators of their cause. And they intended to speak as they would expect representatives of such a cause to speak when they appeared in public outside a court – proudly in support of their ideals, defiant in the face of their enemies. This was their intention from the start, and the spirit of their general instruction to us.51

Joffe’s reference to ‘general instruction[s]’ is important. The Rivonia accused trusted their lawyers, but they did not necessarily take their advice. And they thought for themselves. Speaking specifically of the question whether the accused should plead guilty or not guilty, Joffe writes that ‘we lawyers participated in some of the sessions in which this question was debated. There were others held in private. Finally we were told that they would all enter a plea of not guilty.’ Similarly, when the lawyers pointed out that some of the accused were in different situations from others, so that they might need separate representation by counsel, ‘they rejected the suggestion out of hand’.52

So, too, at a later stage when lawyers and clients debated whether to leave some aspects of the testimony of a prosecution witness, Mtolo, unchallenged – thereby in effect conceding their truth. Joffe writes:

Nelson was a lawyer. He understood fully the implication of what he was saying. Nevertheless, we felt it necessary to warn him of it, and even tried to argue him out of his position … We pointed out that in doing this, he might well be signing his death warrant, for there could not thereafter be any possible denials of guilt or attempts to evade conviction because the full proof of the offence had not been given in court.

Nelson was unmoved. This much, he said, he had understood ever since he had taken a position of responsibility in the political movement … On this occasion the responsibility on him was to explain to the country and the world where Umkhonto we Sizwe stood, and why, and to clarify its aims and policy, to reveal the true facts from the half-truths and distortions of the State case. If in doing this his life should be at stake, so be it … Walter [Sisulu] and Govan [Mbeki] … took the same attitude.53

Perhaps the most unconventional of the decisions the accused made was that while they would testify, and acknowledge their own acts and responsibility, they would simply refuse to answer questions that would require them to implicate others. ‘They had laid down for themselves a very clear basic principle: they would state the facts as fully as possible, but they would not under any circumstances reveal any information whatsoever about their organisations, or about people involved in the movement, where such information could in any way endanger their liberty.’54

The problem with this position was that it had no basis in law. ‘We explained to them that once in the witness box, they were obliged to answer all questions put. They insisted, quite simply, that they would refuse to answer any questions which they thought might implicate their colleagues or their organisations. We told them that in doing so they might well antagonize the judge and make their case worse, not better. They were unimpressed.’ But the accused insisted. As for the lawyers, ‘We had no option but to accept their decision, though we did it at the time unwillingly.’ And the decision the accused made actually set a precedent, which the accused in many future political trials adhered to.55

At least once, moreover, the accused chose to surprise their lawyers. They had decided to plead not guilty. But exactly how would they make these pleas? Usually, this question isn’t a question: to plead ‘not guilty’ one says ‘Not guilty’. But when Nelson Mandela was asked by the registrar of the court to enter his plea, he responded, ‘The government should be in the dock, not me. I plead not guilty.’ Then Walter Sisulu entered his plea: ‘It is the government which is guilty, not me.’ At this point, as Joffe recounts, Judge De Wet intervened:

He said sternly: ‘I don’t want any political speeches here. You may plead guilty, or not guilty. But nothing else.’

Walter went on calmly, unmoved by the judge’s remarks. ‘It is the government which is responsible for what is happening in this country,’ he said. ‘I plead not guilty.’56

And all the other ANC accused proceeded similarly.

This was not the only time that the accused disrupted courtroom convention. When they were first brought to court at the beginning of the proceedings, Nelson Mandela was the first to climb the stairs from the holding area beneath the courtroom. Joffe describes the scene: ‘There was a ripple of excitement amongst the public. He [Mandela] turned to face the public, and gave the thumbs up salute of the African National Congress, with his right fist clenched. His deep voice boomed out the African National Congress battle-cry “Amandla” (Power). A large part of the audience, the African audience, replied immediately in chorus “Ngawethu” (It shall be ours).’

And each of his fellow ANC accused did the same. They continued to do so until someone – Joffe never learned who – decided that henceforth the judge would enter the courtroom before the accused.57 That apparently meant that when the accused entered, they were coming into a court already in session, and subject to the constraints on behaviour in the presence of a judge. These clients, it is clear, had a lot to teach their lawyers – and it is no wonder that the lawyers were deeply impressed.

Meanwhile, the lawyers and clients continued to work together, despite a host of absurd restrictions imposed by the commander of the jail where the clients were held. One important restriction was the rule that the lawyers must leave during lunch; this rule served the twin purposes of preventing Mandela and Sisulu (both by then already convicted prisoners) from eating ‘outside food’ and of enabling the jailers ‘to go off duty and have their lunch’. ‘The hours could NOT be changed for any reason at all. And so we worked like that, preparing our case – three hours in the morning, a two-hour break fiddling around in restaurants in Pretoria [where the jail was located], two hours in the afternoon – and then, for the lawyers, back to Johannesburg to work through into the early hours of the morning, usually at Bram Fischer’s house.’ This was an ordeal, but it was probably also an important part of the process by which the lawyers became increasingly close to each other. ‘It was [also] during this period,’ Joel Joffe writes, ‘that I, and I think all the counsel, began really to know the men for whose lives we were fighting.’58

*

As they grew to know each other, counsel and clients developed the elements of their courtroom strategy. Not all of it was unconventional. Before the accused pleaded not guilty, their lawyers had challenged the indictment. Joel recalled that Arthur was very much in the fore in preparation of all arguments for the defence team,59 and George Bizos recalled that Arthur played a central role here: ‘While we consulted with our clients, Arthur analysed the indictment, drawing attention to ambiguities and inconsistencies. He predicted that the indictment might be excipiable and suggested that a comprehensive application for further particulars should be served so that each of our clients would know what specific acts he performed to make him guilty.’60 This move might seem legalistic, and out of place in the political defence the accused and their lawyers were shaping. But in fact the lawyers meant to be legalistic: ‘We were quite determined that, guilty or not, our clients would get a trial in full accordance with the law. They would not be railroaded.’61

The response of the state was in the hands of Dr Percy Yutar, the Deputy Attorney General of the Transvaal. He had already behaved shabbily in not letting the defence lawyers know when their clients would be brought to court for the first time. Now, in response to the application for further particulars, he reacted in a way that was ‘wilder and more ludicrous than we could ever have expected’. In response to the defence’s requests for clarification of exactly what was charged and against whom:

The replies were curt and repetitive. The almost invariable answer was either ‘These facts are known’, or ‘These facts are peculiarly within the knowledge of the accused’. Occasionally facts were – more emphatically – ‘blatant and peculiarly within the knowledge of the accused’. The prosecution was clearly following a simple precept: ‘You are guilty. Therefore you know what you did. Therefore we don’t have to tell you.’62

This response, so inconsistent with the fundamental premise of the presumption of innocence, did not play well in court. Faced with the imminent dismissal of the indictment, Yutar then offered to hand the defence his opening statement; he claimed that this would be the test of whether the defence was really sincere in asking for further particulars. But an opening statement is no more than advocacy. Judge De Wet was unimpressed; the indictment was quashed. This was gratifying. But unfortunately, when the state in due course produced a new indictment, which the defence counsel viewed as having the same flaws as the first one, the judge showed no interest in the defence arguments and dismissed their renewed motion to quash. Then he rejected a defence motion for a postponement, and directed that the trial begin the following day.63

Yutar’s actions at this stage were typical of his behaviour throughout the case. Obsessed with media publicity, he was underhanded and unethical in his dealings with the defence. Arthur, who was known for his intense reluctance to speak ill of others, described him to Adrian Friedman as a ‘very nasty, self-absorbed and I think not entirely honest man’.64 George Bizos recalled that he was the only one of the Rivonia lawyers who stayed on speaking terms with Yutar.65 Yutar had made a fundamental compromise with the security state: ‘He had no political views and was indifferent to apartheid. Still, he became one of Special Branch’s favourite prosecutors. Policemen like Swanepoel would sit behind the prosecution table to smirk and enjoy the show while Yutar demolished defence witnesses.’66

In the Rivonia trial itself, Yutar’s behaviour outraged the defence team. He at least acquiesced in blatant coaching of witnesses, including two whose memory remarkably improved from a Friday afternoon to the following Monday.67 He was gratuitously cruel, perhaps most clearly when he cross-examined Alan Paton (author of Cry, the Beloved Country), who testified in mitigation of sentence; years later Arthur still found it inexplicable that the judge failed to stop Yutar’s assault on Paton.68 His closing argument, in which – to no apparent purpose – he imagined which Cabinet offices each of the accused might fill in a future government, caused Vernon Berrangé to say in his closing that Yutar’s conduct was ‘not in the best traditions in which prosecutions are conducted in this country’ – a criticism not only of Yutar but of Judge De Wet for permitting it.69

As the case went on, Arthur stopped speaking with Yutar at all; he didn’t explicitly refuse to speak with him, but would just go into court and sit down.70 When, after the end of apartheid, Nelson Mandela had lunch with Yutar as a gesture of reconciliation, Joel recalled that none of the lawyers was pleased – but Mandela said that he ‘could not afford the luxury of revenge’.71 The only compensation for Yutar’s behaviour was that his arrogance led him into disastrous trial mistakes, of which the accused were the beneficiaries.

For Arthur as a Jew it may have been especially dismaying that part of Yutar’s motivation appeared to be his desire to show that a Jew could be as loyal to the system of apartheid as anyone.72 Rivonia put the role of Jews squarely before the public, much as organised Jewry in South Africa sought to escape this. As Frankel observes: ‘All six of the whites arrested at Rivonia came from Jewish backgrounds, as did … many other prominent leftists. The four white defendants at the trial – Bernstein, Goldberg, Hepple and Kantor – were all considered Jews, even those who were resolutely atheistic or of mixed origin.’73 Of course, two of the five lawyers for the defence – Arthur and Joel – were Jewish too.

And what of Judge De Wet, who had granted one motion to quash the indictment and then rejected another that seemed similarly well-founded? Rusty Bernstein – sitting with the other accused on trial – did not think that De Wet had abandoned his fidelity to the principles of South African law. Nor did Joel Joffe. He felt that De Wet was pretty appalling, but that there could have been someone much worse. This was a time when no one knew how far the government might go; Joel recalls that there was a question about whether there would even be a trial, or whether the accused would be summarily executed.

As a person, De Wet struck Joel as ‘obstinate and self-willed’, the awkward result of his pride in his position and his ancestry (his father had been ‘a noted South African judge before him’), combined with his awareness ‘that, as a lawyer, he was unable to measure up to the very high standards of many of the counsel who appeared before him’. That arrogance meant that he would not take instructions from the government. But instructions were not needed, because de Wet was, after all, ‘unquestionably sensitive to the needs of the white society which he believed in and upheld, and also of the government which was its foremost protagonist. He acted out their role, I think, unconsciously, in the firm conviction of his own judicial impartiality, and without any need for a direct word or intervention from any source whatsoever.’74

But Joffe’s account of the trial suggests that De Wet remained in a strange way unpredictable. At one moment he might ask a question that struck the defence as revealing ‘crass prejudice’; and at another he would acquiesce in the accused’s refusal to answer questions that would reveal information about their colleagues – an admirable stand, but one with no support in law at all.75 He would continue to surprise the defence right to the end of the trial.