Читать книгу And Justice For All - Stephen Ellmann - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER EIGHT

Rivonia’s Aftermath

The ramifications of the Rivonia trial would echo through the decades to come. In part, that was so because the trial did not, as the state had hoped, remove the accused from the political scene. Most strikingly, the importance of the accused would grow over the years until the state would find itself dependent on Mandela and his comrades to guide the country to a peaceful transition from apartheid – a transition in which Arthur would play a prominent role. Arthur would remain connected with the accused, assisting them in litigation and in politics and then, after the National Party abandoned its defence of apartheid in 1990, playing an active part in the constitutional negotiations and ultimately taking on, at Nelson Mandela’s request, the leadership of the new Constitutional Court.

At the same time, the trial cemented the personal relations between the lawyers, relations that became an important part of their lives. Arthur and Vernon Berrangé became close friends. So too did Arthur and George Bizos, and Arthur’s ties to Joel Joffe, already profound, no doubt grew deeper – and since George and Joel were young men, these bonds would last the rest of Arthur’s life. Arthur’s relationship to Bram Fischer would not last so long, for Fischer too would end up in prison and not live long, but this relationship, and the relationship with Fischer’s family as well, became a critical foundation for the life Arthur and Lorraine would live in the coming years.

Moreover, for Arthur in particular the Rivonia trial very likely played a role in shaping the legal practice that he pursued over the next decades. This had been a case in which ethical issues played a large role throughout, and it seems probable that the balancing of strict legal rules against broader moral principles remained a concern of Arthur’s over the years. The judgements Arthur reached about this balance in the Rivonia case, and in the litigation about Fischer himself that followed, became a part of Arthur’s ongoing reflection on these issues, and thus a part of his development of a practice that would influence South African public interest law as a whole in the years to come.

*

Let us begin with the accused. As the old joke has it, the lawyers went home, and the convicted men went to prison. Even Rusty Bernstein, acquitted of sabotage, was immediately rearrested in the courtroom, and enmeshed in new legal proceedings. Though he was granted bail, and so was free for the first time since being arrested at Lilliesleaf farm, he was pessimistic:

Whatever the details of the case against me, I can see no chance that I will not be convicted. The evidence from Rivonia alone can convict me of communicating with other banned and listed people; of attending a gathering; of taking part in the activities of banned organisations; and possibly of leaving the Johannesburg Magisterial District – no one knows for sure where the boundary is or whether Lilliesleaf is inside or outside. Each offence can carry a ten-year sentence.1

He did not stay for his trial, nor did his wife Hilda stay for the state to prosecute her. They slipped illegally across the South African border into Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and, after further harrowing travel, arrived in London. They would not return to South Africa until the first post-apartheid elections in 1994, when they joined the other Rivonia accused (except Elias Motsoaledi, who ‘survived twenty-seven years on Robben Island and died of heart disease only days before this moment of achievement’) in Pretoria to see Nelson Mandela sworn in as South Africa’s President.2

Of those who were convicted, one of the loneliest in prison may have been Denis Goldberg. Ironically, this was because he was white. Apartheid applied even to convicted prisoners, and so Denis was held in Pretoria Central, along with other white political prisoners, but far from his black comrades on Robben Island. Denis’s wife Esmé was barred from visiting him during most of his years in prison; his children were not allowed to visit at all for the first eight years, and then were allowed to come ‘every second year’. Fortunately, and surprisingly, Arthur’s friend Hillary Kuny was permitted to become a regular visitor, and those visits sustained him. In 1982, she would draft a memorandum to the authorities that requested his release, and he would be freed in 1985, based on a promise to abstain from further violence against the state. Denis, as convinced an opponent of apartheid then as before, felt he could make this promise because there would be other ways to fight apartheid, and indeed he became an active part of the European anti-apartheid movement.3 He returned to live in South Africa after the end of apartheid, worked for some years as an adviser to the Ministry of Water Affairs and Forestry (he was, after all, an engineer), and in 2009 received the National Order of Luthuli (Silver) in recognition of his role in the liberation struggle.

The other accused, six Africans and one Indian, were imprisoned on Robben Island. Their incarceration there was meant to be harsh, and for some years it was. But the Rivonia accused and the other political prisoners who joined them ‘on the Island’ decided that their struggle continued even in prison. ‘We would fight inside as we had fought outside,’ Mandela wrote. Over the years they largely defeated their captors’ rule. They were not free, but Nelson Mandela would write that ‘in early 1977, the authorities announced the end of manual labour. Instead, we could spend our days in our section. They arranged some type of work for us to do in the courtyard, but it was merely a fig leaf to hide their capitulation.’4

Over the years, new generations of political prisoners would arrive on the Island, reflecting the resurgent struggle against apartheid. Old and new encountered each other. For some, such as Dikgang Moseneke – who was sent to the Island at the age of 14, and who would later become the Deputy Chief Justice of South Africa – their years on Robben Island would be among the most significant of their lives.

Meanwhile, the state became, increasingly, the prisoner of the accused. Mandela has described the gradual initiation of negotiations between himself and his captors in his autobiography. George Bizos assisted in this process by passing messages between Mandela and the ANC in exile. Arthur too remained connected with Mandela, and represented his wife Winnie in an important stage of her fierce struggle against the authorities, as we will see. By the time Nelson Mandela was released, he was no longer on Robben Island but instead was living in a cottage inside the confines of Victor Verster Prison near Paarl, his meals cooked for him by a prison guard who had come to idolise him, and receiving visitors from the state and from the anti-apartheid movement. He and his comrades were gradually released as the state fumbled its way towards negotiations: Govan Mbeki, by then in ill health, in 1987; Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni and Walter Sisulu, in October, 1989; and finally, triumphantly, Mandela himself on 11 February 1990. Mandela would lead the ANC in negotiations and become the first President of a democratic South Africa, and many of his Rivonia comrades would also play a part in shaping the new, post-apartheid South Africa.

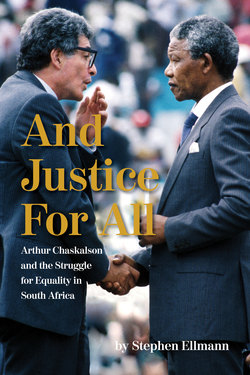

When Mandela came out of prison, he at once turned to the task of reaching out to the people who had supported him, and whose support and trust he would need in the delicate negotiations to come. Just days after his release, the ANC held a ‘welcome back’ rally in Soweto. Among the people welcomed to the stage that day were Arthur Chaskalson and George Bizos. George recalls that the crowd cheered, ‘Viva, Arthur Chaskalson, viva! Viva, George Bizos, viva!’5 Three years later, as President of post-apartheid South Africa, Mandela would select his former lawyer Arthur Chaskalson to be the President of the new Constitutional Court.

*

By then three decades had passed since the end of the Rivonia trial. When Mandela spoke at the inauguration of the Constitutional Court in 1994, he observed that he had last been in court to find out whether he would be sentenced to death. Over those decades, decades of both despair and gradually increasing hope, Arthur would resume his successful commercial practice, and become a leader of the Bar. But he would also represent a range of clients who were in various ways the heirs or successors to the Rivonia accused: from another set of saboteurs, part of the African Resistance Movement, to Winnie Mandela, to anti-apartheid students and ANC guerrillas. And Arthur’s relationships with the other Rivonia lawyers would be deeply important to him. The year that they worked together was arduous and, as his wife Lorraine recalled, exhilarating; the bonds that grew between Arthur and the others were very strong and lifelong.

Vernon Berrangé and Arthur’s friendship began during the Rivonia trial. Berrangé was a complex man. A one-time Communist, he had fought with his fellow members and then left the party; he had ‘a penchant for high living, hunting and fast cars’; in truth, he loved a fight, and ‘revelled in danger and fighting’.6 He was a man who acquired nicknames: the ‘Diviner’ or ‘Isangoma (a diviner or healer who exorcises an illness’).7 His ferocious cross-examinations no doubt reflected all that. Arthur might have seemed almost Berrangé’s opposite, a man always careful and restrained, intellectual rather than combative. But the difference between them was by no means as great as that. During a break in the trial, Arthur and Lorraine went to the Berrangés’ farm in Swaziland so that Arthur could work with Berrangé on the cross-examination of the turncoat state witness Mtolo that Berrangé would soon undertake. While they were there, Lorraine became very ill with tonsillitis, and Berrangé’s wife Yolanda took care of her. After that, Arthur recalled, they became very good friends. After Yolanda died, they continued to see Vernon, and he visited them at their Johannesburg home.8 The Chaskalsons, including their sons, also visited the Berrangé farm; Matthew was terrified because he was told that there were a couple of crocodiles lurking there.9

George Bizos and Arthur had known each other since Arthur’s first year as a student at Wits. But they were quite different people, George outgoing while Arthur was reserved, and they did not become close friends until Rivonia bound them together. After the case was over, they went somewhat different ways: George continued to maintain a practice heavy in political cases, while Arthur resumed his mostly commercial practice. But the two men remained close friends – so close that George could hook Arthur into a major trial, the Delmas treason trial of the 1980s, by introducing him to the clients as the leader of the defence team (without having told Arthur in advance; Arthur glared but said nothing);10 and so close that Arthur would help launch George’s autobiography by saying at the launch party that ‘George has such an incredible memory for detail, that he even can remember things that never happened’.11 They would work together on some important cases over the years, and they would also speak out together when they saw the independence of the bench and the Bar jeopardised in the new South Africa.

Joel Joffe continued to handle political cases as an attorney, but decided to leave South Africa. As he and his wife Vanetta prepared to move to Australia in 1965, however, Arthur and Lorraine told them, ‘We’ve got a house in Cape Town for a month; why don’t you join us?’ The Joffes said yes, but at the end of that month the South African government seized Joel’s passport – apparently out of sheer spite. That meant that if and when Joel left South Africa he wouldn’t be able to go back to South Africa, and it also caused Australia to consider him undesirable. So he and his family wound up moving instead to England.12

Joel was leaving South Africa with little except his training and ability to enable him to get started in England. His family had promised him £2,500, but something went wrong and his father decided he couldn’t do it. Joel perhaps mentioned this to Arthur – and a few days before Joel was to leave, Arthur arrived with a cheque for the full amount and gave it to Joel. Then Arthur forgot about it, and never mentioned it again over the following decades – another instance of Arthur’s generosity.

Meanwhile, Joel landed on his feet in England. He had with him a letter of recommendation from Bram Fischer to a law firm that represented the Trades Union Congress in Britain; they offered him a job on the strength of this letter, but told him that they were a small firm and wanted to keep the profits for the present partners. So at that point he hesitantly went to see Mark Weinberg, another member of the circle of friends that Arthur and Joel had been part of at Wits, at the insurance company which Weinberg now managed. Weinberg hired him – because, Joel claims, he misunderstood the instructions on a psychological test he had to take and answered all the questions in the opposite way from what he was supposed to. Joffe, Weinberg and Sydney Lipschitz, another of Arthur’s friend from Wits, would go on to co-found the insurance company Hambro, which became a great success. It also became a place where a number of left-wing South Africans in exile found employment. For their achievements, both Weinberg and Lipschitz were knighted, and Joel, who had gone on to public service as the president of Oxfam, became Lord Joffe.

In 2010, Joffe told his interviewer Adrian Friedman that just a few years earlier he had reminded Arthur of the £2,500. Joffe had never spent it; instead, he had invested it, without Arthur’s knowledge. By this time, Arthur’s generous gift had grown to around £75,000 and Joel said, ‘Can I please give it back to you?’ Arthur refused – but eventually they did a deal in which Joel gave the money to charities that Arthur selected.

Joel did take one other thing with him when he emigrated: a trove of papers from the Rivonia trial and from Nelson Mandela, which he had acquired because of his role as the attorney in the trial. He consulted them as he wrote his book about the trial in 1965 (‘While looking for a job I had some free time,’ he explained.13) Then he handed the papers to a library, and asked that they hold on to the papers until freedom came. Then 1994 dawned. Joel explained in 2010 that it wasn’t entirely clear who owned these papers, Mandela or Joffe, but they arrived at a happy resolution. Mandela was to speak at a memorial lecture; Joel would present the papers to him, and he would present them in turn to the Legal Resources Centre (the public interest law organisation that Arthur co-founded in 1979), and specifically to the LRC’s director, Geoff Budlender. At the lecture, Mandela took the papers and handed them not to Geoff but to Arthur, who was also on the stage. When Arthur corrected him, Mandela said to the audience, ‘You now know why I appointed Arthur as President of the Constitutional Court, because he always gives me the right advice.’ When I talked with Joel in 2016, negotiations were almost complete that would enable the LRC to sell these papers for a very large sum of money, which in turn would go – as Joel had intended it should – to the LRC’s endowment.14

As Joel told me in 2016, he and Arthur were very close friends, even after Joel left the country, and even though they probably exchanged only six letters in all the years they were apart. Joel’s estimation was surely correct, however scanty their correspondence. When the Chaskalsons visited England in 1970, 1973 and 1976, they each time spent a few days at the Joffes’ home; Matthew largely based himself at their home when he came to England on his own in 1980.15 Arthur said that if Christ returned to earth, he would probably resemble Joel Joffe. Joel helped to found the fund-raising arm of the Legal Resources Centre in Britain, the Legal Assistance Trust, and remained a trustee in 2016.16 Joel and Arthur also went together in 1988 to the apartment of Stephen Clingman, to encourage him to write the biography of Bram Fischer – a hero to both Joel and Arthur. Clingman writes that ‘Both [Joel] and Arthur Chaskalson were in at the birth of this project, and I dare say without their encouragement I would never have begun it, let alone completed it.’17 Joel provided crucial financial support for that biography, as he has, more recently, for this biography of Arthur.

*

Finally, Bram Fischer. Arthur and Bram had become even closer during the trial. Bram’s daughter Ilse said that Bram loved Arthur, though Bram wouldn’t have used that word, while his daughter Ruth said that the relationship between Bram, Arthur and Joel was especially close, perhaps a kind of love.18 The days and years that followed the Rivonia trial were anything but kind to Bram – but nothing that happened undercut the intense bond between Arthur and Bram, and indeed between Arthur and Bram’s family. Bram’s story is eloquently told by Stephen Clingman, whose account I rely on here; it’s important to tell Bram’s story, because it was a story that all those who cared for Bram, such as Arthur, lived as well.

With the Rivonia trial coming to an end on 12 June 1964, the Fischers left the following day on a vacation. Bram and his wife Molly and a family friend, Elizabeth Lewin, planned to drive from Johannesburg to Cape Town. As they travelled at twilight, Bram was forced to swerve to avoid a motorcyclist and a cow on the road. He lost control of the car and it left the road and fell into a ‘deep pool of water’ in the notoriously dry Free State. Fischer and Lewin got out; Molly, in the back seat, never emerged. Fischer’s desperate dives into the pond were unsuccessful. She was dead, one day after the end of the Rivonia trial.19

Back in Johannesburg the next day, family and friends gathered at the Fischers’ home. Bram somehow maintained self-control – until, as his biographer records, Lorraine Chaskalson arrived. Lorraine and Molly had become very close during the trial too; Lorraine, not on good terms with her own mother, had responded to Molly’s great warmth as a person.20 When Bram saw Lorraine that day, ‘he just wept on her shoulders’.21

Seven days after the Rivonia trial ended, Molly Fischer was buried. Nevertheless, Bram and Joel were the ones who went, shortly after the funeral, to Robben Island, and then to Pretoria Central, to discuss with their convicted clients whether or not they wished to appeal. (They didn’t; several of them had no ground for an appeal, and even those who did might not have gained much in the end.) Fischer didn’t acknowledge his own loss as he met with his clients. Nelson Mandela, reflecting on those moments, would write of Fischer that ‘as an Afrikaner whose conscience forced him to reject his own heritage and be ostracized by his own people, he showed a level of courage and sacrifice that was in a class by itself’.22

On 9 July Fischer was detained by the security police – but oddly he was released less than three days later. Perhaps the police were trying to scare him into leaving the country, but he didn’t. Instead, on 23 September, he was arrested again, and now he was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act. He faced ‘an inevitable jail sentence’, which – to judge from the sentences his co-accused subsequently received – quite likely would not have exceeded five years.23

Bizarrely, however, the government had issued Bram with a passport two days before his 23 September arrest, after having previously refused to do so. Bram explained to the American scholar Tom Karis that it was ‘practically unknown to get bail’ in Suppression of Communism Act cases. But the passport, issued to enable Bram to argue a commercial case in London before the Privy Council, changed the calculus. ‘It was therefore on this rather extraordinary ground,’ he wrote, ‘namely that a passport had been issued to enable me to go to the Privy Council, that I was given bail in order to leave the country.’ In court, Bram declared, ‘I am an Afrikaner. My home is South Africa. I will not leave South Africa because my political beliefs conflict with those of the Government ruling the country.’ Perhaps the magistrate who granted bail was also impressed by the testimony of the attorney Rissik, who would ultimately post Bram’s bail money. He said of Bram that ‘I have absolute faith in his integrity. I would accept his word unhesitatingly, confident that he would carry it out’.24

Bram made the trip to London. He argued his appeal and won it. Then, despite being urged not to return to South Africa, where he faced the likelihood of conviction and imprisonment, he chose to return. Perhaps he did so out of political calculation, or perhaps out of moral obligation. Joe Slovo, a leading Communist who tried to get Bram not to return, spoke ‘of Bram’s “rather touching fidelity” as a revolutionary prepared on one level to sacrifice his life, but on another committed to personal honour and the importance of carrying out a political undertaking’. And then, having returned, he faced trial, which began on 16 November 1964. The evidence accumulated, though it included a prosecution witness, a longtime Communist comrade of Bram’s, agreeing with Bram’s lawyer that he was ‘a man who carries something of an aura of a saint-like quality’.25

Then, on Monday, 25 January 1965, Bram estreated his bail. Harold Hanson read out a letter to the court from Fischer, a letter Hanson claimed to have received that morning, but that in fact he had picked up from the Fischers’ home over the weekend. George Bizos also had a sense of Bram’s plans:

One Friday we walked back and forth in the long passage outside his office while he told me that he had come to say goodbye. For my own protection he would give no further details. He was worried that his actions might place his children in danger and asked me to help them if they were detained. We embraced. And he hurried off.26

Citing the accumulation of oppressive laws and the necessity for radical change to avoid a future of ‘appalling bloodshed and civil war’, Fischer wrote:

To try to avoid this becomes a supreme duty, particularly for an Afrikaner, because it is largely the representatives of my fellow Afrikaners who have been responsible for the worst of these discriminatory laws.

These are my reasons for absenting myself from Court. If by my fight I can encourage even some people to think about, to understand and to abandon the policies they now so blindly follow, I shall not regret any punishment I may incur.

I can no longer serve justice in the way I have attempted to do during the past thirty years. I can do it only in the way I have now chosen.27

He remained underground for 294 days. Along the way Rissik, who had posted Bram’s bail, was reimbursed. In one sense, Bram accomplished little politically – he made little progress in reconstructing the underground Communist Party, in particular. It also seems fair to say that he was a man in personal distress during these months, and understandably so. At the same time, what he did had symbolic significance: ‘On Robben Island Nelson Mandela and his colleagues came to hear that Bram was underground: though it reflected the kind of commitment they expected from him, they were elated, and it lifted their spirits … [His daughter] Ilse Fischer, meeting Africans of all descriptions, was told time and again how much her father was revered.’28

Almost as soon as Bram went underground, the Johannesburg Bar moved quickly to have Fischer struck from the roll. ‘Justice Minister Vorster publicly challenged the legal profession to condemn Fischer and take appropriate action against him if it were sincere in claiming the role of guardian of the rule of law,’ and the Bar responded within a matter of days. Arthur ‘wrote to the [Bar] council asking for reasons’ for its decision. ‘They replied that they don’t give reasons for their decisions.’ Sydney Kentridge and Arthur Chaskalson represented him, Sydney (the more senior of the two) taking the leading role. (George Bizos writes that both Sydney and Arthur ‘were livid at the Bar Council’s actions at striking Bram from the roll’.)29 Bram’s daughter Ilse thinks that perhaps Bram reached out to Arthur, whom he knew much better than Sydney did, to ask them to represent him.30 Fischer had himself been a leader of the organised Bar for many years, and he was deeply distressed by the rejection by his Bar colleagues. He tried to explain his actions in a letter to another lawyer:

When an advocate does what I have done … it requires an act of will to overcome his deeply rooted respect of legality, and he takes the step only when he feels that, whatever the consequences to himself, his political conscience no longer permits him to do otherwise. He does it not because of a desire to be immoral, but because to act otherwise would, for him, be immoral.31

In court, in hearings in late October and early November 1965, Sydney Kentridge would argue that ‘It was doubtful … if there were any member of the Bar that had known Bram who would be prepared to stand up and say, “He is a less honourable man than I am.”’ But his legal challenge was unsuccessful, and he was struck from the roll, in a judgment by the same judge, De Wet, who had presided over the Rivonia trial. George Bizos felt that ‘nothing hurt Bram … more than this case and this decision, for he had acted from the highest of principles, and yet had been considered unworthy and dishonourable by his colleagues’.32

When Bram was arrested, on 12 November 1965, George Bizos recalls that he ‘spotted Arthur Chaskalson alone in a corner at the back of the [main criminal court in Johannesburg, where Bizos was already engaged in a trial], and we were able to talk briefly about Bram’s arrest’. ‘He urged me to continue with the case and to control my sadness and despondency. Along with senior members of the Bar, he believed that Bram would be detained incommunicado and tortured. The security police would want to know his underground contacts. Arthur had been briefed by [attorney] William Aronsohn to visit Bram at Ilse’s request.’33

Arthur and others feared for the worst, but they reacted by mustering the resources they had to try to protect Bram. As it turned out, Bram was not being held for interrogation but rather for trial. Although General Hendrik van den Bergh ‘was curious how Arthur knew that Bram wanted to see him, he sanctioned the visit. Bram was as well as could be expected.’34 Arthur recalled that that day, the day after Bram’s arrest, ‘his attitude … was one of self-reproach at having allowed himself to be captured’.35

One other, chilling note was struck in this period. Roman Eisenstein recalls that General Van den Bergh called Arthur after Bram’s arrest and said, ‘Mr Chaskalson, I’ve got your friend.’36 The unspoken message, it seems, was that the security police believed that Arthur and Bram were in league, and wanted Arthur to know that he was in their sights too.

The result of Bram’s period underground was that the charges against him were now multiplied. George Bizos and Sydney Kentridge represented him; Arthur was involved in another political trial, which he offered to drop, ‘but Bram felt it important that he continue’. Even so Arthur was able to assist and even attend the trial when the other case was not in session.37 The trial began in late March 1966; the case against Bram would take only a week to present. Bram himself did not testify but rather, like Nelson Mandela at the Rivonia trial, he made an unsworn statement from the dock. In it he declared:

I accept, my Lord, the general rule that for the protection of a society laws should be obeyed. But when the laws themselves become immoral, and require the citizen to take part in an organised system of oppression – if only by his silence and apathy – then I believe that a higher duty arises. This compels one to refuse to recognise such laws …

My conscience, my Lord, does not permit me to afford these laws such recognition as even a plea of guilty would involve. Hence, though I shall be convicted by this Court, I cannot plead guilty. I believe that the future may well say that I acted correctly.

Now he spoke without ambivalence of the necessity for his having gone underground:

My Lord, it was to keep faith with all those dispossessed by apartheid that I broke my undertaking to the Court, that I separated myself from my family, pretended I was someone else, and accepted the life of a fugitive. I owed it to the political prisoners, to the banished, to the silenced and to those under house arrest not to remain a spectator, but to act. I knew what they expected of me, and I did it. I felt responsible, not to those who are indifferent to the sufferings of others, but to those who are concerned. I knew, my Lord, that by valuing above all their judgement, I would be condemned by people who are content to see themselves as respectable and loyal citizens. I cannot regret any such condemnation that may follow me.38

His words did not change the result (nor did he expect they would – he had expressly declined to ask for forgiveness or plead for mercy). He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. He would never be free again.

Meanwhile, life went on, and Arthur’s connections with the Fischer family remained and even deepened. The families grew to be social friends and more than that – Bram’s daughter Ruth felt the Chaskalsons had become part of her extended family, always welcoming and always ready to do whatever they could for her.39 One of the ways that Arthur could help was with his professional skill. Bram’s daughter Ilse had been directly involved in helping him to go underground without being stopped by the security police, and she had resumed contact with him during his time in hiding. Bram had also brought her onto the Central Committee of the illegal Communist Party, and she would be officially listed by the government as a Communist within a week of Bram’s trial. She was, in other words, seriously vulnerable herself. Perhaps while Bram was underground, Ilse went to Arthur to discuss what she should do. For the first time she laid out to him all the facts about her own involvement. He was unfazed. With her he considered her circumstances, took into account her goal of remaining in the country, and came to a conclusion: he advised her to stay out of sight for a while.40 As he had with his friend Toni Shimoni in earlier and more innocent times, Arthur showed his ability to take a situation in hand and guide someone he cared about in negotiating it. He would advise Ilse’s sister Ruth as well, and she too remembered him always being incisive and clear.41

Fischer’s son Paul, who had cystic fibrosis, earned an honours degree at the University of Cape Town and returned to Johannesburg. He and his sister Ilse regularly had dinner at the Chaskalsons’ home.42 But Paul succumbed to his illness. The government refused Fischer permission to attend his son’s funeral. The family felt that Arthur, their friend, was the natural person to give the funeral eulogy.43 The strength of Arthur’s feeling for Paul, and for his father, was evident in his words. Saying that ‘Paul had the same integrity and commitment “which made Bram the great man that he is”’, Arthur continued: ‘He was Paul Fischer; a boy who grew into a young man, who lived fully, and was loved by all who knew him … He would not have wanted us to gather here today to pay tribute to him; but that is our right and he is not here to prevent it, nor to prevent our saying that we are glad that he lived and that we knew him.’44

At least once Arthur provided legal advice to Fischer while he was imprisoned. We know this from the memoir of the Rivonia trialist Denis Goldberg, who writes:

Bram, through his daughter Ilse, asked Arthur Chaskalson if there was an arguable case to put to a court to win the right of access to news [for the political prisoners at Pretoria Central]. He replied that there was a very weak case. Bram did not want to embarrass his fellow advocate by asking him to argue a weak case and allowed the matter to drop.45

Fischer’s respect for Arthur’s legal judgement is evident here, as is his consideration for Arthur’s standing as an advocate.46 But apparently Arthur was in touch with Bram about this matter only through Ilse. While George Bizos, as Bram’s counsel, was able to visit him regularly in prison, Arthur, for these purposes evidently treated as just a friend, could not visit because only family members could have social visits with prisoners.47

While Bram was in prison, Ilse and her future husband Tim Wilson decided to get married. They wanted to marry in the prison, with Bram, but prison rules prevented him from meeting with more than two people at once, and the minister would have been one person too many. So they were married in a small chapel, with only a few guests, who included the Chaskalsons and the Bizoses. Lorraine Chaskalson was much involved with the planning of the ceremony and may have cooked for it.

Fischer, in prison, developed prostate cancer. Prison authorities grossly neglected his care, though perhaps with no ‘malicious’ intent; at one point, Denis Goldberg, one of the Rivonia accused now serving his life sentence, nursed Bram through painful nights. The family pressed for Fischer’s compassionate release, and consulted with Arthur about how to accomplish this.48 Ultimately Fischer was transferred to his brother’s house, suitably far from Johannesburg and any conceivable political impact this dying man could have had. His brother’s house was re-designated as a prison and there he died. The Prisons Department claimed his ashes.

Arthur spoke at the funeral, held on 12 May 1975. It hadn’t been planned that he would speak. The leading Afrikaans writer André Brink had become deeply attached to Bram and asked to speak – but then the day before the funeral he backed out, citing pressure from his own father. Thirty years later, when Brink encountered Fischer’s daughter Ilse at a party, he was still embarrassed by this. Arthur agreed to read Brink’s statement, thus taking on whatever risk there was of attracting the security police’s attention. He also read messages from five other people – messages from three more people ‘could not be read because the senders were banned’. He was the only speaker. (A few other Johannesburg lawyers, including George Bizos, attended.49) For Brink, Arthur reportedly said, ‘Fischer had proved that “Afrikaner” meant infinitely more than someone identified with a narrow ideology. “If Afrikanerdom is to survive,” [Brink] went on, “it may well be as a result of the broadening and liberating influence of men like Bram Fischer.”’50

Arthur also spoke for himself, but because that hadn’t been planned, he didn’t write his remarks down.51 However, according to one newspaper report, he pulled no punches in what he said: ‘Mr Chaskalson said Bram engaged in a struggle for equality, for freedom from domination, freedom from control by imperial powers, for an end to racialism and for the building of socialism.’ Arthur went on to say: ‘His decision to remain was made in the full knowledge that few of his comrades remained, who were not in prison, and there was little hope of any immediate success. His arrest, trial and the many years of imprisonment that followed, he saw as a continuation of the struggle to which he had committed himself.’52

The link between the Chaskalsons and the Fischers continued. Years later, in the 1980s, Ilse Fischer Wilson, Bram’s older daughter, would work as a librarian and then a paralegal at the Legal Resources Centre. When Ilse and her husband Tim finally received passports in the mid-1980s, after decades of trying, Arthur happened to be in her office and she told him the news. He was carrying a pile of papers of some sort, and he was so happy that he threw everything in his arms to the ceiling. Ilse and Tim remained friends of Arthur and Lorraine’s for life, and were among the guests at Lorraine’s 70th birthday party, which Arthur and his daughter-in-law Susie organised just months before he died.53 Ruth Fischer Rice and her husband were part of the Cape Town branch of this multi-stage party.54

*

Arthur, Joel and George continued to honour Bram Fischer’s memory through the years. In the 1980s Arthur and Joel would persuade Stephen Clingman to write Fischer’s biography. In the 1990s, after the end of apartheid, the Legal Resources Centre would establish a Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture. In 1995 Nelson Mandela gave the first of these lectures; Arthur Chaskalson gave the third, in 2000. Other Fischer lectures have been established as well, including a series now hosted by Rhodes House and another at the University of the Free State. Much earlier – probably when criminal charges were filed against him, since at this point he would have known his office would have to be closed55 – Bram had given Arthur his lawyer’s silk robe (though it was too small for Arthur, who was much taller than Fischer), his law library and his desk. The law library would find a lasting home at the LRC, and Arthur would take Fischer’s desk with him to his chambers as the first President of South Africa’s new, post-apartheid Constitutional Court. (The undersize robe was stored by the Chaskalsons in a playroom with a leaky roof, and after Arthur’s death Matthew found that it had been ‘completely destroyed’ as a result of storm damage.56)

In the 1990s efforts were also made to have Fischer restored to the roll of advocates. Initially those efforts were blocked on the ground that ‘only practising advocates may appear on the roll; someone who is no longer alive can no longer practise; therefore Bram could not be reinstated’.57 But the last were now first in South Africa, and Parliament was prevailed on to pass legislation to remove this barrier, the Reinstatement of Enrolment of Certain Deceased Legal Practitioners Act 32 of 2002. George Bizos would rely on this Act in successfully petitioning the High Court, on behalf of Fischer’s daughters, to reinstate him, in the 2004 case of The Application for the Reinstatement of Abram Fischer on the Roll of Advocates.

The High Court was fully sensitive to the historical implications of its decision. In 1965, as he approved the striking of Fischer’s name from the roll, Judge De Wet had quoted from a 1905 decision growing out of the Anglo-Boer War, Ex parte Krause, in which a leading judge of that day had spoken in favour of ‘as much as possible drawing a veil over the acts which were committed during the course of the war’. De Wet went on: ‘If the respondent were to apply for readmission at some future time, similar considerations may apply. It is impossible for this Court to foresee what will happen in the future. We are concerned with the laws in force at the present time and with the structure of the society as it exists in this country at the present time.’58 Now the High Court, sitting as a racially diverse three-judge panel, wrote:

It was, in our view, therefore appropriate that the application for his reinstatement also served before a Full Bench; but even more appropriately, before a court as representative of the diversity of our society as possible. This is the kind of society that Fischer fought for. The future time to which reference is made in the judgment for his striking off has now arrived.59

As all of these interconnections reflect, the bond between Bram and Arthur was strong and deep. It is tempting to think that perhaps Bram, close as he was to Arthur, might have offered Arthur advice about how he could best negotiate the years to come. He might have suggested to Arthur that he too should join the Communist Party, in which Bram had lived his life – or rather that Arthur should avoid joining any political party and instead should pursue a career that was emphatically lawyerly, as R.W. Johnson has suggested.60 But those who knew Bram respond that it simply was not Bram’s way to offer advice like this. George Bizos himself told me that Bram had not advised him and Arthur to be non-political.61 Joel Joffe emphasised Bram’s disposition not to offer such advice, and added that if Bram had advised people to join the Communist Party, half the Johannesburg Bar would have done so because Bram was so persuasive.62 Ilse Fischer Wilson also doubted that Bram had advised Arthur about how to handle the years ahead.63 Bram’s biographer, Stephen Clingman, wrote to me that he

never got the impression in talking with [Bram’s] colleagues – Chaskalson, Bizos, Joffe – that Bram ever expected them to follow him into illegality of any kind. He had a profound respect for individual choice, refusing to influence them in this respect – and in this respect (another paradox) he influenced them profoundly: a different kind of politics.64

Whether Bram gave Arthur advice about how to negotiate the years to come must remain uncertain. Bram was not a man to press his views on others, but that might not have been what happened at all. Arthur, who as we’ve seen had been profoundly affected by the trial – growing, as Denis Goldberg recalled, close to the accused in a way he had not been initially – might have felt that he wanted Bram’s advice and sought it out. Or he might not, and in the end whether he asked for advice is less important than what Arthur concluded about the situation he faced.

It is worth pausing for a moment on one point: whether Arthur, because of Fischer’s example or for any other reason, became a member of the Communist Party. Arthur was dogged by this charge during his lifetime. It appears that members of the security police may have imagined that Arthur took over the leadership of the Communist Party from Bram; thus Matthew Chaskalson, when he was working in 1991 for a commission investigating the city of Johannesburg’s intelligence bureau, encountered an ‘organogram’ which showed the Politburo at the top and, far down, the Legal Resources Centre.65 But no one has reported finding actual evidence to support these notions. On at least one occasion, moreover, Arthur successfully insisted on the insertion of an erratum notice in a book, The Awkward Embrace, which had asserted that he was a Communist Party member.66 Ken Owen, a prominent newspaper editor, went so far as to send someone to research the files at the Kremlin to look for evidence, but to no avail.67 After Arthur’s death, the now-legal South African Communist Party issued a statement claiming him as a member – but it subsequently withdrew the claim in the face of sharp rebuttals by Arthur’s surviving colleagues and friends.68 Among them was George Bizos, who declared: ‘Arthur was a democrat. There were no secrets between Arthur and myself. I know that Arthur was not a member of any political party. He would not join any organization that would place any impediment to his absolute independence.’69

Paul Trewhela, who spent some time in jail with Bram and fell out with the Communist Party, finds sufficient reason to believe Arthur was a Communist in the statement by Jeremy Cronin of the SACP that Arthur ‘was an SACP delegate to the CODESA (Convention for a Democratic South Africa) negotiations back in 1991’ – and in Arthur’s failure to deny this assertion.70 In fact Arthur had denied the assertion that he was a Communist, in insisting on the erratum page just mentioned, and Cronin himself, for his part, said that the Party ‘fully accept[ed]’ that its claim of Chaskalson’s membership was mistaken.71 But there was in any case no reason for Arthur to deny this assertion; representing a party is not the same as joining one, as advocate Paul Hoffman pointed out.72 In fact, well before CODESA, in 1990, Arthur had already joined the Constitutional Committee of the ANC. Undoubtedly Arthur was committed to the ANC’s cause in the negotiations, but he did not join the ANC.

To me, the comment by Arthur’s close friend and colleague Geoff Budlender, responding to a newspaper article by Tony Leon (former head of the Democratic Party), is compelling (and it’s worth adding that Leon himself, when I spoke with him, implied that he had misunderstood the circumstances when he wrote):73

It is matter of public record that Chaskalson was never a member of the SACP. The question of his political affiliations arose in the Sarfu case, when Louis Luyt applied for him and several other members of the Constitutional Court to recuse themselves. Dr Luyt’s attorney wrote to Chaskalson calling on him to respond to a series of questions relating to the recusal application. In his reply, Chaskalson stated: ‘For a brief period while I was a student I was a member of the Liberal Party. Apart from that I am not and have never been a member of any political party.’

So if Mr Leon asserts that Chaskalson was a member of the SACP, he is asserting that Chaskalson, acting in his capacity as president of the Constitutional Court, deliberately lied to a litigant before the court on an issue that was central to an application for his own recusal.74

It is true that admirable men, such as Walter Sisulu and perhaps Nelson Mandela himself, did conceal their Party membership – but the world in which they made their choices, the world of revolutionary politics, was not Arthur’s world. Like Budlender, I cannot believe that Arthur would have taken such a step.

But what were the lessons that Bram’s life imparted to those, like Arthur, who would make their life in the law over the coming decades? Undoubtedly there were many. Fischer gave much and took little, and his example of humility and commitment must have been tremendously inspiring. I want to focus here, however, on the issue that the final months of Fischer’s freedom so vividly posed: when is it morally right for a lawyer to violate the law? We’ve already seen Fischer’s answer, as he formulated it in his statement from the dock during his trial: ‘when the laws themselves become immoral, and require the citizen to take part in an organised system of oppression – if only by his silence and apathy – then I believe that a higher duty arises. This compels one to refuse to recognise such laws.’75

We can also understand Fischer’s answer in a different way – by taking account of what laws he in fact did violate. His colleagues in the Rivonia case understood that Fischer might well be guilty of crimes under the Suppression of Communism Act and the Sabotage Act, and they knew, of course, that he had estreated his bail. They also knew that he had undertaken the defence of the accused in the Rivonia case despite being himself involved in some way in the events taking place at Rivonia; they hadn’t known this before the case began but it had become evident during the trial. Thus they knew that Bram had departed at least to some extent from ordinary legal ethics, for a lawyer himself implicated in the acts for which his clients are on trial must face a potential conflict of interest between his own legal fate and that of his clients. When they realised this – at the moment that they saw a piece of paper with Bram’s handwriting on it being presented in court – their reaction, Joel Joffe said, was admiration of Bram’s bravery.76

But it seems unlikely that Arthur and his colleagues were fully aware of how far Bram had departed from the law. His biographer reveals that Bram had followed his commitment to his clients’ political cause very far indeed, and memoirs published since then have added additional details.

Outside the trial itself, Bram helped two Rivonia prisoners, Goldreich and Wolpe, to flee the country; he may also have given prior approval to their escape from jail. He also urged one of his Rivonia clients, Denis Goldberg, to try to escape (which turned out to be impossible).77 He encouraged Bob Hepple, who had been arrested at Rivonia but now was being called by the state as a witness for the prosecution, to flee the country, and provided him with ‘the detailed plans for the escape’. Hepple, himself an advocate, writes that he met secretly with Fischer to discuss his options. ‘This is a highly dangerous undertaking for us both. According to the rules of professional conduct, he should not be talking to a potential state witness. But I know that Fischer places his moral obligations to his “family” of political comrades above the rules he would strictly observe in an ordinary case.’78 Fischer also disposed of a car that had been used by Denis Goldberg, to avoid its being found at a cottage that was being used as a ‘safe haven’.79

Fischer’s law-breaking also extended to the trial itself. Since he had himself been involved in the debates over Operation Mayibuye, he must have known the truth about Govan Mbeki’s view that this proposal had been adopted, and so he must have known that the accused were testifying falsely to obscure this. Since it was Fischer who settled on the legal strategy of denying that Operation Mayibuye had been adopted, it seems very probable that he encouraged the accused to testify as they did. Perhaps most remarkably, at trial he took documents offered in evidence by the state that suggested potential targets for sabotage and passed on the information to his underground Communist Party colleagues, along with similar suggestions from some of the accused.80 In other words, he used his position as a defence lawyer to assist in the commission of further crimes. Denis Goldberg, not a lawyer, saw the choice Bram had made clearly: ‘Clearly there was a conflict: Bram was senior counsel for the defence, therefore part of the state machinery, while being a valued comrade. He resolved these conflicts in the only way consistent with his belief in freedom: he acted as a revolutionary – and it is in action, ultimately, that these moral conflicts are solved.’81

Nearly twenty years ago I wrote an article about Bram Fischer’s law-breaking, under the title ‘To Live outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity’. I argued that Fischer’s choices may not have been the best ones, but that they were ‘the morally justified choices of a remarkable man’.

Though he violated many of his obligations under the law, he did so out of obligation rather than out of indifference to it. In countless ways, he honoured the bonds between people, and the obligations of humanity; his rigorous understanding of those ties led him to his fate. In this important sense, he always remained honest – faced with excruciating choices, he was prepared to take steps that were illegal and covert but only in the service of principle, in a lifelong effort to be, in his own qualified but determined words, ‘as honest as it’s possible for a human being to be’.82

I also asked, however, what the impact of Fischer’s choices might have been on other lawyers, and ultimately on the rule of law in a post-apartheid South Africa. Did his example, however impressive in and of itself, potentially teach others to disregard the bounds of law for more selfish reasons? This is a question that cannot be definitively answered – and even a rough answer to it may only emerge over the years, as post-apartheid South Africa pursues its own destiny. But I did argue, and with Arthur very much in my mind:

Many anti-apartheid lawyers, even in the midst of apartheid’s rule, remained deeply convinced of the moral significance and value of law. For these lawyers, Fischer’s life surely did not teach the lesson that law could be casually dispensed with in order someday to restore law. I suspect that, just as his gentle, self-effacing style of lawyering may have helped shape a generation of South African anti-apartheid lawyers’ courtroom tactics, so his decisions to violate the law out of principle contributed to many principled lawyers’ determination, not to disregard the obligations of legal ethics, but to fight relentlessly and courageously to overturn the world of apartheid. Whether or not lawyers like this ever felt themselves obliged to depart from the law – not widely and habitually but only, as Fischer did himself, in circumstances of surpassing moral crisis – the lesson they brought to the new South Africa would not have been disrespect for legal order. Rather they would have sought, and did seek, a Bill of Rights, as Albie Sachs writes in his remarkable memoir, to eliminate the horrors that ‘compelled the most honest amongst us to become the biggest dissemblers.’83

Did this appraisal capture Fischer’s impact on Arthur correctly? I asked Joel Joffe about the issue of Bram’s breaking the law for moral reasons, and he responded by asking if I had read Bram’s speech from the dock about this, which I have already quoted. He went on to say that he and Arthur saw this issue as Bram had, without their really having had to say much about it to come to this understanding.84

Arthur also wrote to me about Bram in May 2001, after I sent him a draft of this article. He spoke first about lawyers and law-breaking:

I am sure that many if not most lawyers have broken the law at some stage of their careers. Parking in a no parking area, breaking the speed limit while driving, buying liquor from an unlicensed restaurant, and a range of other transgressions which might be regarded as minor or possibly as the contravention of laws that were not binding on the conscience of the particular lawyer. No doubt gay lawyers and judges broke the law when same sex relationships were criminalised. And many South African lawyers would have broken apartheid laws concerned with residence, provision of liquor to black friends when that was prohibited, employing black workers without a permit to do so, hiding people from the police or helping them to escape, etc. etc. One can multiply the examples.85

The sense that this passage conveys is that Arthur took it for granted that ‘many South African lawyers’ would have broken apartheid laws, ranging from laws that created the routine injustices of apartheid, to those that in decent societies would be entirely appropriate but that in South Africa functioned to support apartheid’s oppression. Arthur and Lorraine themselves had sheltered a fugitive, and Arthur had helped Nelson Mandela move around while underground – so it seems fair to read Arthur here as speaking about himself as well as other lawyers. What justified such conduct? Arthur answered:

The point is, I think, that there is a distinction between criminal conduct that reflects dishonesty, and conduct that does not. In Bram’s case, there was no question of dishonesty. Everything he did was from a principled position. Whether you agree with him or not, it is difficult not to admire the consistency in his conduct, and the integrity which led him to place principle above personal security and well-being.86

Arthur’s point in focusing on dishonesty here, I believe, is that Bram acted out of principle rather than from some lesser motivation. I don’t think he meant to say that any act involving false statements, for example, was unjustifiable, because later in his email he suggested a comparison of Fischer’s actions with ‘members of the resistance against the Nazis who committed any number of “crimes” in the execution of their resistance. Apart from the acts of sabotage, they created false documents, stole property [from] the Germans, lied about their activities etc. There may even have been lawyers amongst them.’87 Surely it is, indeed, inconceivable that someone who created false documents to save Jews from extermination thereby demonstrated ‘dishonesty’.

That Arthur recognised circumstances in which even the creation of false documents or the telling of lies – acts normally taken to reflect dishonesty – could be morally justified is hardly extraordinary. It is also worth noting that Arthur did not include these actions in the list of the acts of law-breaking that ‘many South African lawyers’ would have committed. A person who violates the law out of principle cannot violate all laws; he or she must assess whether principle justifies the violation of each particular law that comes into question. If legal work can be fruitfully done without lying, then lying is not justified – even if other acts, perhaps at first blush graver than lying, such as shielding fugitives from the police, are quite legitimate. Arthur’s email does not suggest that he or those who shared his convictions considered their preparedness to act falsely as anything but a very last resort.

That still leaves considerable room for manoeuvre. Rules might be obeyed in form but not in substance – as in the Rivonia advocates’ selection of their attorney, who in turn formally selected them. Clients whose testimony might not have been true could still be represented as long as the lawyer did not know that their testimony was false – and even if the lawyer, by advising the client about the legal situation that he faced, might have educated the client about what falsehoods could be to his advantage. For Arthur, though not for Bram, that may have been the understanding he had of the Rivonia clients’ testimony on Operation Mayibuye. And in years to come, Arthur and the other lawyers who handled political cases in South Africa all seem to have tacitly concurred in accepting the financial support of the International Defence and Aid Fund, which for many years delivered its support – by then illegal under South African law – in the guise of donations from individuals of good will.

Arthur’s friend and Legal Resources Centre colleague Geoff Budlender similarly reflected on the Defence and Aid funding. In the NUSAS trial (which we will look at in Chapter Nine),

a letter arrived from [a] … solicitor in London, who said I have a client in Geneva, … who’s a professor … who’s very concerned about academic freedom … and … and he wants to support academic freedom in South Africa. I believe you have some clients and … er … what’s the case gonna cost? What everybody knew then was that it wasn’t from the professor from Geneva … it was obviously from the [Defence and Aid] fund.88

Budlender, who was an articled clerk at the time, commented: ‘I don’t think anyone thought too hard about it. Well, I didn’t. I was a baby in the game … Arthur must have thought about it. He must have figured it out.’ And looking back, Budlender said they had been ‘sailing close to the wind … It didn’t feel like that at the time.’89

But if Arthur in principle accepted that ethical lawyers might sometimes break the law for the sake of justice, as Bram Fischer had, he surely did not conclude that he should follow Bram’s path of defiance of the law. In the years to come, he would earn a reputation for exceptionally scrupulous law practice, and for similarly law-minded behaviour in his private life. The moments when he dramatically crossed or almost crossed clear legal lines all belonged to the period before Rivonia. After Rivonia, he charted a different course, one that made him an advocate of standing and influence, able to employ South African law in new and powerful ways against South African injustice. The course he chose safeguarded that powerful position by very carefully ensuring that the law could not become a weapon against him. He was still capable of reading the law to permit obedience in form but not in substance, as he seems to have done in accepting funding from a ‘Geneva professor’ in the NUSAS case, but he did not simply depart from the law. No doubt his real and deeply felt commitment to the law was in itself reason for others to respect the lines he drew between what the law prohibited and what it (perhaps just barely) permitted. Whether Bram Fischer urged Arthur to follow this course we will never know; but in the chapters to come we will see that Arthur indeed did proceed on this path. We will see, moreover, that doing so involved considerable delicacy in drawing lines between what could and what could not be done; it required, in short, a lawyer of Arthur’s skill.

There is one more point to consider from Arthur’s email to me. This is his objection to a comparison I drew between Bram Fischer and Oscar Wilde. With my father Richard Ellmann’s sympathetic understanding of Wilde in mind, I wrote (in the published version, which may have differed somewhat from the draft Arthur read): ‘The sense that Wilde stood for principle even as he violated the law … resonates with the life that Fischer led, and each became an avatar of a liberation he would not live to see. Moreover, Wilde, who was a socialist as well as an artist, may in his own way have had a moral rigour quite comparable to Fischer’s.’90 Arthur responded:

The problem I have with the comparison with Oscar Wilde is that he led a life of great personal indulgence; Bram did not …

I also think that the comparison you draw may be misunderstood here, and hurtful to many people. Many will see Wilde as he is often depicted as self-indulgent, pleasure seeking, and concerned primarily with his own interests, and may understand the last part of your article as trivializing Bram’s commitment.

Whether Arthur (or I) was right or wrong in this debate is not my concern now. Rather, what seems most important about what he said is that it reflects how deeply attached to Bram Arthur remained, a quarter-century after Bram’s death, and that it is clear how much Arthur weighed in his moral calculus the issue of whether someone was acting out of duty or self-indulgence. What Arthur admired in Bram he would insist on in himself. He would always try to act out of duty.