Читать книгу 39 Days of Gazza - When Paul Gascoigne arrived to manage Kettering Town, people lined the streets to greet him. Just 39 days later, Gazza was gone and the club was on it's knees… - Steve Pitts - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

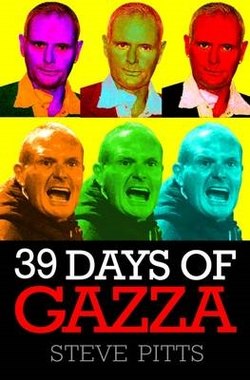

GAZZAMANIA!

ОглавлениеALTHOUGH Ladak’s financial fortunes were heading in the opposite direction to that of his newfound partner, his fortune was far from huge in professional footballing terms. He had looked at both Port Vale and Peterborough United, and admitted he had been ‘very impressed’ by everything he had seen at the latter. He made an offer which Barry Fry – at various times manager, owner, chairman and director of football at Peterborough – turned down. Less than a year later, Darragh MacAnthony, an Irish multi-millionaire with a personal fortune of £200 million, bought his way into Peterborough. He spent around £5 million in his first year buying out Fry and assembling the most expensive squad in that club’s history.

That sort of money was beyond Ladak, and he had to set his sights lower. Fry, one of lower-league football’s most endearing characters, pointed him in the direction of Rockingham Road, also believing such a move could be just what Gascoigne needed. ‘He’ll certainly create loads of enthusiasm and put bums on seats,’ he said.

Fry was friendly with Peter Mallinger, the chairman of Kettering Town, who, after a dozen years of limited success, wanted out. He had earned the appreciation, if not enduring love, of supporters for rescuing the club after the previous owner, Mark English, had done a runner to leave it on the brink of closure and at the mercy of police investigations and the Inland Revenue. Mallinger, who had made his money with a string of wool shops, didn’t have the financial clout for a serious bid for Football League status, but he steadied a ship that had been heading for the rocks and oversaw a few moments that almost made it all worthwhile, the highlight of which had been a trip to Wembley for the final of the FA Trophy.

He had financed the club to the tune of around £100,000 per season, but even that only kept the club treading water. The possibility of a takeover involving Gascoigne held out the promise of some sort of return on his investment. Perhaps it would even make the perennial dream of a place in the Football League a little more than wishful thinking.

Mallinger had been involved in the boardroom at Newcastle United when a charismatic and supremely talented teenage Gascoigne had first come to nationwide attention with his immense footballing ability and cheeky grin. Gascoigne’s star may have faded over the ensuing years, but Mallinger was thrilled that he was being put up as the man to take his club forward.

Although the first public sighting of Gascoigne in Kettering was 24 September, the ball had really begun to roll earlier in the month, after a telephone call between Mallinger and Ladak on 6 September. The two men met in the sponsors’ lounge a few days later, and within two hours they had agreed a price. Ladak asked if he could bring Gascoigne along to see the set-up for himself, and a few days before that frenzied Saturday-afternoon visit he had been smuggled into the ground, along with Ladak, to meet with Mallinger in his small office overlooking the pitch.

They kept the lights switched off in the hope that nobody would see Gascoigne and spark the inevitable gossip and rumour. But to no avail. An incredulous player, arriving for training after finishing his day job, had spotted what he was sure was the England legend in the car park, and immediately told the manager, Kevin Wilson.

Wilson had won 42 caps for Northern Ireland in a distinguished playing career that had seen him make more than 600 appearances for the likes of Chelsea, Derby County, Ipswich Town and Walsall. After hanging up his boots, he had gone into coaching, then management, and had been in charge at Kettering for the best part of two years. He recalls looking up to Mallinger’s office at the side of the main stand and seeing a crowd of people. Although he couldn’t pick Gascoigne out with the lights off, it wasn’t hard to put two and two together, especially as he had picked up on the football grapevine that Gascoigne and his business partners had previously shown an interest in buying Peterborough.

Unaware they had been rumbled, the meeting continued. With Ladak and Mallinger having previously shaken hands on a price, there wasn’t much else to discuss before the lawyers got to work. Mallinger had been diagnosed with leukaemia shortly before the approach from Ladak and his illness gave him another good reason to get out, while Ladak, the driving force and money-man of the consortium, was keen to get the deal done as quickly as possible. While they talked, Gascoigne ventured to the large window looking out onto the pitch to watch Wilson conducting the training outside.

Mallinger is a true gentleman of the non-League game and Kettering’s boardroom hospitality was among the best in semi-professional football. Before his guests had arrived, the consummate host had laid out nibbles, bottles of lager and beer and, conscious of Gascoigne’s problems, some bottles of Coca-Cola and Lucozade.

As Mallinger walked, with Ladak, between his own office and the general office next door, he was surprised to hear the drinks cabinet being opened behind him. He turned back to find Gascoigne sitting behind his desk uncorking a bottle of Harvey’s Bristol Cream that had been gathering dust, a leftover from the Christmas raffle. When it became clear his guest was going to drink the sherry, Mallinger tentatively offered him a paper cup. Gascoigne waved him away and drank straight from the bottle.

The group stayed in the office for another half-hour or so before Mallinger suggested they walk along the back of the main stand to the sponsors’ lounge. Mallinger says he was shocked at Gascoigne’s appearance, describing him as ‘almost anorexic’, and the alcohol worked quickly on his thin frame. As they walked down the steps from the offices, Gascoigne stumbled and needed the help of the ever-present Jimmy Gardner to prevent him falling.

‘Imraan had told me that Paul wasn’t drinking anymore and I wasn’t sure what he’d make of it,’ says Mallinger. ‘There was him in one room telling me Paul wasn’t drinking and Paul in the other room drinking my bottle of Harvey’s Bristol Cream. As was often the case with Paul, nobody said anything and we carried on as if nothing had happened. But it was quite surreal.’

In the sponsors’ lounge, Gascoigne downed a couple of glasses of white wine, while Mallinger took Ladak to the side of the pitch to be introduced to Wilson. Mallinger told Wilson of the proposed sale, but there was no mention of Gascoigne’s involvement at this stage, although a few days later Ladak met Wilson and told him of his plan to make Gascoigne manager. Wilson was assured there would be a role for him on the same wages.

Although there had been strong speculation that Gascoigne was buying a share in the club, he did not put his hand in his pocket. Ladak had agreed a price with Mallinger, £160,000 for outright ownership, and the deal was that Gascoigne would put up around 30 per cent of the money needed to buy out Mallinger and minor shareholder Trevor Bennett. He would then not take a salary for his first five months as manager as they implemented their business plan.

As it turned out, despite promises that Gascoigne’s share was on its way, Ladak would never see a penny, and there was speculation as mid-October approached that the deal had fallen through. But, following the 3–0 FA Cup fourth-qualifying-round victory over Gravesend & Northfleet on 22 October, an impressive result against a team doing well in the division above, Ladak claimed the deal should be concluded within a few days.

His optimism was the result of further talks with the accommodating Mallinger. With Gascoigne’s money not forthcoming, Ladak had sought a revised agreement whereby Mallinger would be paid the same price but with the share supposedly being put up by Gascoigne paid in instalments. Mallinger never received all the money he was due.

Ladak has been asked many times since why he took the gamble on someone as unstable as Gascoigne had proved to be in the years prior to the pair putting their ‘consortium’ together.

But he had been bewitched by the Gascoigne who scored a spectacular goal for Spurs against bitter rivals Arsenal in the FA Cup semi-final of 1991, on his way to becoming a national icon. Gazza was a Tottenham and England legend. Here was Ladak, a young man with no experience of football other than as a fan, working in partnership with his boyhood hero on an exciting new venture that would surely lead to bigger and better things. And he had put it all together, even if that had required little more than a telephone call and a three-hour conversation – and, of course, a significant amount of money.

‘It was a call out of the blue,’ Ladak said when asked to explain why he had gone after Gascoigne. ‘The three players I’ve admired most are Maradona, Ronaldinho and Paul. Ronaldinho’s under contract and Maradona’s not really management material.’ But was Gascoigne?

Gascoigne had convinced him that he could keep his drinking, and other problems, under control, and Ladak was having no truck with the doubters. He was keen to assure people that Gascoigne was a reformed character who was as committed to Kettering Town as he was. ‘From what I’ve heard, the one worry that people have got is that Paul may not be around for that long,’ he admitted to reporter Jon Dunham. ‘He has invested in the club. He is part of the consortium and he will be involved in the long term.’

Although he did not always answer his phone, Gascoigne gave every indication of having a genuine passion for the task ahead. While he was recovering from the operation on his neck, he often retreated to Champneys. There he had been transformed from the thin and wan man who had so disappointed Anna Kessel and shocked Mallinger to someone who appeared in reasonable health, other than having a big plaster on his neck, when he was unveiled as manager three-and-a-half weeks after Kessel’s Observer article was published. The pictures taken during and after the press conference on 27 October show a man enjoying being back in the limelight for purely footballing reasons. He was the charming, wise-cracking man who had captivated the nation, and it was good to see.

When Ladak spoke to him in the weeks leading up to that press conference, Gascoigne could be humble and keen to impress, even though he had found it odd being interviewed for a job by a man 10 years his junior. He studied videos of Kettering playing, and they talked about the type of players they should recruit. The disgraced former Manchester United and Chelsea player Mark Bosnich was mentioned as a possible goalkeeper. Other names bandied about included former England strikers Les Ferdinand, Teddy Sheringham and Steve McManaman.

Ladak could barely contain himself and spoke of signing ‘very big former internationals who have played Champions League football’. When the name of Graeme Le Saux, capped 36 times by England, was speculatively thrown into the hat, Ladak retorted, ‘Bigger than that.’

Ladak and Gascoigne also spent time discussing how they would take the playing staff full-time and introduce a reserve team, something that had been beyond the means of Mallinger. The Football League was the target – in three to five years, according to Gascoigne, who had convinced Ladak that he was not at fault for his rapid departure from his three previous ventures, as far apart as Lincolnshire, China and the Algarve. That was in the past and he had got his act together. He would deliver, and Ladak was willing to put his faith in a man he had idolised from the White Hart Lane stands.

Ladak, like so many over the years, was determined to give him the benefit of the doubt. He knew that Gascoigne’s name alone would bring in the crowds and he gave every impression that Kettering Town could blitzkrieg their way into the Football League. Gascoigne was just the man for attracting the players needed to achieve that goal.

Even those who thought his ambition naive at this ruthless level of semi-professional football lauded his enthusiasm. And Gascoigne had another big advantage: his name alone would open the door to potential sponsors. Gascoigne claimed as many as 40 were keen to get involved with him at Kettering.

The promises that he made to Ladak were the same ones he went on to make to the supporters of the club and the people of Kettering in general. Aware that his first venture into football management after years of negative headlines had attracted scepticism, Gascoigne met the critics head-on: ‘I’m not going in there saying, “I’m Paul Gascoigne, I want respect.” But I’ve always been a good person and that’s why I’ve never fallen out with any of the managers I’ve worked with these past 23 years. They respect me and not one has advised me not to do it. I’ve just got to make sure I do the right things as a manager. I won’t be making the club look like a circus. I shall be doing the job properly like the top managers.’

He wanted to be judged at face value, not by what the good folk of Kettering had been reading in their newspapers: ‘Local people will get to know me and when they do they will realise that I am an honest and genuine guy, and I will always try and give a good account of what’s happening at the football club.’

And he did try. After the game against Stafford Rangers, he had spent a good half-hour signing autographs, posing for pictures, shaking hands and exchanging small talk with a queue of excited football fans, young and old, which snaked around the back of the stand. He had stepped out from the boardroom to meet them with a smile on his face after a crowd had gathered around the entrance to chorus, ‘Gazza, Gazza, Gazza’ without a break for 20 minutes. They gave every indication they would carry on all night if necessary, and he clearly enjoyed the adulation. Mike Capps recalls, ‘They were asking him to sign just about anything … shirts, programmes, bits of card. If the kids had picked stones up off the ground, he’d have signed them.’

Indeed, for much of his time at Kettering, Gascoigne demonstrated a tolerance of supporters that put to shame those who would sneak out through side doors to avoid pesky fans. He was a genuine man of the people. Many top footballers, and other sportsmen, refuse to sign autographs for fear of them ending up on eBay or endorsing dodgy products. Gascoigne would sign almost anything put in front of him. He seemed to find it hard to say no.

And so Gazzamania came to Kettering, and it wasn’t only football fans who were whipped into a state of great excitement at the prospect of Gascoigne picking their team. The local MP, councillors of all political persuasions, business leaders and the solid, ordinary folk of a town hardly renowned for its football hysteria all threw their arms open to a man they felt was going to put Kettering in the spotlight. ‘To say the club had been put on the map nationally and internationally would be an understatement,’ says Kevin Meikle, who, in the way only sport seems to manage, got himself promoted from loyal fan to managing director in the aftermath of the takeover.

Local councillor Chris Smith-Haynes says there was ‘absolute elation’ in her neighbourhood at the news that Gascoigne was to be the club’s manager. ‘It was like the second coming,’ she enthuses. ‘There was great excitement. People were stopping and talking in the streets; there was a feel-good factor.’

Kettering MP Philip Hollobone couldn’t contain his enthusiasm as he predicted a positive impact ‘on all businesses and shops in the town’. The Tory politician gushed, ‘It is great for Kettering that a footballer as professional as Paul Gascoigne should take an interest in our main local football club.’ Gazza-inspired graffiti began appearing on the walls of buildings and fences in Kettering as the excitement spread. ‘Welcome to Kettering Gazza’ and ‘Gazza’s Army’ were among the sentiments spray-painted in the town centre.

As for the players, there was genuine excitement at the prospect of playing for a man they all claimed as their favourite footballer, even if there was regret over the obvious shadow cast over Wilson’s future. ‘When I was a kid, Paul Gascoigne was my hero and the chance to meet Gazza, it’s like you’re really nervous,’ said Wayne Diuk, a defender in his seventh season with the club. ‘But a lot of us were loyal to Kev and we were thinking, “If Gazza’s coming in, then where’s Kev going?” I didn’t want to see him stitched up.’

Andy Hall, a teenager busy trying to establish himself in the team, said, ‘When it was first being said, I just thought it was all talk. Then Gazza walks into the dressing room and he’s standing there, and you think, “Hey, this is an opportunity for me.”’

More experienced players found it hard to take it in. Christian Moore, a no-nonsense veteran of the non-League game at the age of 32, said Gascoigne had won a special place in his heart when, as a teenager, he had watched him at the 1990 World Cup finals. Moore’s striker partner, Neil Midgley, a lifelong Tottenham supporter, answered his phone to find Paul Davis telling him he had Paul Gascoigne wanting to speak to him. Midgley was so excited he jumped out of his chair to stand almost to attention as he spoke to the legend. ‘I felt like I should be saluting,’ he recalls. ‘Gascoigne was a big, big hero of mine. I kept telling myself, “It’s Paul Gascoigne, I’m going to be playing for Gazza. I’m going to do my best to make sure I’m a part of this.”’

* * *

Although the majority of fans were thrilled at the prospect of Gascoigne coming to Kettering, club director Dave Dunham remained one of a sizeable minority who had to be convinced. ‘It had been put through Imraan that Gascoigne’s problems had been well documented but that he was reformed and recovered and was able to take the job on,’ he recalled. ‘But it was fairly obvious to me from the outset that he hadn’t and he wasn’t able to do it. Everyone was aware of Gascoigne’s history. Unless he was a completely reformed character, I just wondered how it was going to be possible.’

However much those behind Gascoigne hoped he had his alcoholism under control, he had been seen drinking wine, cider, brandy and sherry at the club and around the town even before he had moved into the manager’s office. The newspapers had found out about Gascoigne’s session in The Beeswing, and landlord Jim Wykes’s phone lines were red hot with calls from journalists asking what he had been drinking and whether he had behaved himself. To protect his idol, Wykes told them he had only had soda water and not the cider and large glass of white wine that Gascoigne had drunk.

Wykes said Gascoigne did not appear affected by the alcohol on leaving the pub. But it seemed he had caused offence in the club’s boardroom a short while later by spitting a mouthful of wine out onto the carpet, apparently without a second thought. At a club which prided itself on its hospitality, the reaction was one of silent horror. ‘This was Paul Gascoigne and people had stars in their eyes,’ said Dave Dunham. ‘But what do you do? Nobody said anything and it was just cleared up.’

Mallinger – who, until the time he stood down as chairman, was a stickler for standards and insisted that visitors to his boardroom wore a jacket and tie – was mortified. Not least for his wife, Barbara, who had to mop up the spillage, while Gascoigne stood nearby causing further offence in what was typically a rather genteel environment with language peppered with expletives.

With the deal yet to be completed, Gascoigne went off to conduct more interviews to promote his DVD and look for other ways to make money, always suspicious that some people were trying to exploit him.

Meanwhile, Ladak busied himself with the club he was about to take charge of. He went along to Compton Park, the Northampton home of the United Counties League side Cogenhoe United, to watch what was basically a youth team lose 2–1 in the Northamptonshire Football Association’s Hillier Cup.

He was regularly in touch with those at the club and a few alarm bells had already sounded with Wilson over the way that Ladak would seek him out for a chat about the team. He felt uncomfortable discussing selections, substitutions and tactics with somebody he barely knew. And it was an issue that would be central to Gascoigne’s list of complaints less than two months later.

Somebody else not at ease was Wilson’s second in command, Alan Biley. The striker had enjoyed a lengthy playing career with the likes of Everton, Portsmouth, Derby County and Cambridge United before coaching in America, Holland and Greece. He had then settled into the non-League game and joined his former Derby teammate Wilson as assistant manager in February 2004, shortly after Wilson’s appointment.

Biley had seen Ladak watching training and initiating discussions, and approached Wilson to explain his doubts. ‘I’m not sure I want to be here,’ he confided to the manager.

Wilson left it to Biley to make his own decision, and on the eve of the FA Cup third-qualifying-round trip to St Albans on 8 October he informed Wilson that he was leaving. The game was important to Kettering because victory would leave them one round away from the first round proper and the possibility of a lucrative tie against a League club. As they travelled to Hertfordshire, Wilson told the players that Biley was unwell, only giving them the true story after the goalless draw.

Three days later, Kettering, their results improving by the week, thumped St Albans 4–0 in the replay at Rockingham Road in front of a Tuesday evening crowd of more than 1,200 fans. The following Saturday’s 4–0 league defeat of Leigh RMI saw an almost identical attendance. The Gazza effect was becoming evident. Prior to his first appearance at the club, the Poppies had played four home league games and had averaged 912, with a highest gate of 966. By the time they took on Gravesend & Northfleet on 22 October, the final game before Gascoigne’s appointment after a month of relentless speculation, the attendance had climbed to 1,647.

Like many of the fans awaiting the arrival of the living legend, Ladak may well have looked at his boyhood hero through rose-tinted glasses. But he was only one of many people willing Gascoigne to seize this opportunity. Despite the well-documented problems he may have had since his days as England’s talisman, there was still plenty of goodwill and affection for him.

One of those prepared to throw his hat into the ring with Gascoigne was Paul Davis, who had been involved in professional football for his entire adult life, having signed as an apprentice for Arsenal at the age of 16. He went on to become a key member of the dominant Gunners side of the late 1980s and early 1990s, picking up medals as a First Division, FA Cup, League Cup and European Cup Winners Cup winner. Although, unlike Gascoigne, this quietly spoken Londoner did not play for the full England team, he was capped at Under-21 level on his way to 447 appearances for Arsenal, scoring 37 goals in his 17 years at Highbury.

After his playing career had ended with a brief spell at Brentford, Davis went into coaching with the football love of his life, Arsenal, and became a qualified FA coach. Like Ladak, Davis was hopeful that Gascoigne could make a success of the Kettering Town job, and agreed to join him as assistant manager. He, too, bought into Gascoigne’s vision. ‘He is still the passionate, enthusiastic guy he was when I first played against him when he was 17,’ Davis stressed. ‘He has enormous qualities that he can pass on to younger players.’

Of course, Davis was aware of the problems that had haunted Gascoigne over the previous decade, but thought the new venture could keep him focused on football. ‘We only look at the positive side of Paul,’ he pointed out.

Davis also hoped that assuming managerial responsibility for a squad of footballers who would obviously look up to him would help bring out the best in Gascoigne. In purely footballing terms, he was a genius who had played under some of the best managers in the business. He could draw on the experience gained from working for the likes of Terry Venables (QPR, Tottenham, Barcelona, England), Walter Smith (Glasgow Rangers, Everton, Scotland) and Bobby Robson (Ipswich, Newcastle, Porto, Barcelona, England). If he could combine that with his outstanding football instincts, while maintaining sobriety and interest, Davis felt he had a chance of taking the first steps on what Gascoigne was hopeful would be a long career in football management. But, as always, matters unrelated to his footballing ability would decide whether that would be possible.

Venables, Smith and Robson were among the many big names to send Gascoigne messages of support. Like so many others, they must have had their fingers crossed. They knew that, if all went well, it could help him to begin to deal with the mental-health issues that had caused him so much suffering.

* * *

As the pro-Gazza graffiti began appearing on the walls in the town centre, so one of the questions asked at the time was how many other footballers could have generated such excitement in a town like Kettering? Sure, the club could claim the likes of Tommy Lawton, Derek Dougan and Ron Atkinson among its former managers, but it had never made it into the League and was hardly a hotbed of football fever.

‘You have to ask yourself who else would get the town that excited,’ Mallinger wondered. ‘I can’t think of anybody. He’s just one of his own, unique. And if he turned up sober now and did it all again he’d get the same reaction.’

Even Dave Dunham, who had grave doubts about the project from the moment he first met Gascoigne in the boardroom prior to the takeover, admitted he would struggle to name any other Englishman, other than David Beckham, who could have had whipped up such a storm.

‘If it had been somebody of Gascoigne’s standing in football but without everything else that goes on around him, would there have been the same reaction?’ he speculated. ‘If it had been any of his teammates from that Euro ’96 team, such as Gareth Southgate or Stuart Pearce, would everybody have got so worked up? I don’t think so. But it was Gascoigne and he has always had that sort of aura. There were a lot of people in Kettering who were just overtaken by it all.’

Dunham had been deeply unimpressed when meeting Gascoigne for the first time. Gascoigne had finished his session in The Beeswing and arrived in the boardroom shortly before 2pm – two-and-a-half hours later than the agreed itinerary – and Dunham firmly believed from that moment on that Gascoigne’s involvement would end in tears. But, despite his misgivings, even he was moved to admit, ‘As for putting the club in the local, national and international domain, it was fantastic. Perhaps that was Imraan Ladak’s intention all along.’

However, even Ladak was surprised by the level of interest shown in Gascoigne. Despite agreeing with Mallinger not to comment publicly until the agreement was signed, he was unable to stop himself sharing his thoughts with the local paper. ‘The phone hasn’t stopped ringing,’ he said. ‘I knew the fact that Paul was involved would attract media attention but it has gone way beyond what I expected.’

And he wasn’t the only one. Mallinger found it impossible to concentrate on everyday business as the few phones at the ground rang incessantly. ‘As soon as we confirmed Paul Gascoigne was to be involved, the media were almost permanently camped on our doorstep,’ he recalls. ‘Sky TV made Rockingham Road their second home and other TV and radio stations from all over the world were constantly on the telephone. I was telephoned by a radio station in Melbourne on my way home in the evening to talk live on their morning programme.’ What did he tell them? ‘Anything I could think of about Paul. If anything, he was even bigger news over there.’

The fascination with Gascoigne seemed without limit, and the media storm was to become even more intense as the press conference was staged to unveil ‘Paul Gascoigne the manager’ to the waiting world.