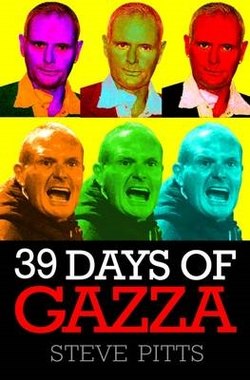

Читать книгу 39 Days of Gazza - When Paul Gascoigne arrived to manage Kettering Town, people lined the streets to greet him. Just 39 days later, Gazza was gone and the club was on it's knees… - Steve Pitts - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

GAZZA? YOU’RE HAVING A LAUGH!

ОглавлениеSHORTLY before midday on 24 September 2005, on a typical Saturday at The Beeswing public house in Kettering, Jim Wykes, the landlord, did what he always does at that time. He left his staff to welcome the lunchtime crowd and climbed the stairs to his private quarters to make himself a bacon buttie and put his feet up. It was ‘landlord’s hour’, and he was only to be disturbed if his sister had nipped over from Melbourne to ask for him. As he hadn’t seen her for 40 years, he didn’t think that too likely.

Wykes hadn’t even got the bacon into the frying pan when he got a call from his barman, Ryan Wilson, summoning him back down to the bar of his recently refurbished pub. ‘Has my long-lost sister turned up?’ he demanded.

‘Better than that,’ came the reply. ‘It’s Paul Gascoigne and Jimmy Five Bellies.’

Wykes, a keen football fan, told Wilson to stop winding him up. Gascoigne was the greatest English footballer of his generation, a huge celebrity who was always in the newspapers for one reason or another. Why would the hero of Italia ’90 and Euro ’96 be in his pub, a stone’s throw from the Rockingham Road home of the non-League football club Kettering Town? But Wilson was adamant it was Gazza.

‘I said, “Leave me alone, my bacon’s on,”’ Wykes recalls. ‘I told him they would be lookalikes, that there’d be some sort of competition on in Kettering that afternoon.’

‘I’m telling you, Gazza and Five Bellies are sat in your bar watching telly,’ Wilson insisted.

Curiosity got the better of the landlord, who went downstairs to see whether he was having his leg pulled. Wykes could only see the back of the two men’s heads as they sat facing the large TV screen in the corner. Still sceptical, he stepped out from behind his bar and walked around to stand in front of the pair. All doubts were instantly washed away.

A big man, Wykes knelt down on one knee in front of Gascoigne, who was sitting in a comfy lounge chair. Before he could speak, Gascoigne said to him in his thick Geordie accent, ‘You’re not proposing to me, are you?’

Wykes laughed, stood up and asked Gascoigne what he was doing in his pub.

‘It’s all a bit hush-hush, but you’ll find out soon enough,’ was the reply.

The doors had only just opened and there was only one other person in the bar. ‘Leave the lad alone,’ Wykes was told.

‘But this is Gazza,’ he replied. ‘He’s a legend.’

While they spoke, his barman began texting friends to tell them of the celebrity in their midst. They dashed to the pub, saw Gascoigne for themselves and began texting their mates. In a rural market town the size of Kettering news travels quickly, and within 20 minutes the pub was packed with people eager to catch a glimpse of Gascoigne, many clutching their copies of his autobiography, England replica shirts and football programmes for him to sign. Failing that, they grabbed beer mats or simply held out their arm for Gazza to scribble on.

‘My daughter’s boyfriend told me he was in The Beeswing,’ remembers Chris Smith-Haynes, a Conservative councillor for the Kettering Borough Council ward which included Rockingham Road. ‘I thought he was talking rubbish.’

On arrival, Gascoigne’s close friend, Jimmy ‘Five Bellies’ Gardner, had ordered a soft drink for himself and a pint of cider for Gascoigne, and, before the pub became swamped, he asked for another cider and a large glass of white wine. ‘On the house,’ said Wykes, who had to pinch himself to be sure that he was buying a drink for a footballer he had idolised at his peak a decade earlier.

The Beeswing is a large pub, and the rapidly growing crowd began to visibly concern Gascoigne. His mood, chilled on arrival, appeared to darken. ‘He was quite happy to sign the autographs at first but when it got too busy he got a bit agitated,’ says Wykes. ‘He saw all these people piling in and thought any minute the press was going to arrive. Jimmy Five Bellies was asking people to give him some space. He didn’t look comfortable.’

Wykes had welcomed the odd celebrity to his pub before, and photos of ex-royal butler and I’m A Celebrity… star Paul Burrell as well as former EastEnders actor Gary Beadle were on display behind his bar. He asked Gascoigne if he would make it a hat-trick. ‘I said to him, “Before you go, my wife would like a picture of you behind the bar with her.” He sneered at me, he didn’t like that at all. He didn’t say anything but just gave me a look that said “no”. The way he looked at me, I knew not to push it. He didn’t want to be pictured behind a bar.’

It was hardly surprising. With his time as the talisman of English football becoming no more than a memory, Gascoigne had been fighting a long-running and frequently unsuccessful battle against alcoholism and hated the press for the way they had regularly caught him out. Pictures and stories of Gascoigne’s drunken escapades were good sellers for the tabloids, and there was no shortage of paparazzi looking to make a few quid for a shot of Gazza with a drink in his hand or staggering out of a nightclub. Gascoigne knew only too well that a photo of him behind a bar, however innocent, could end up embarrassing him in a red-top.

Sadly, Gascoigne had fallen off the wagon so many times since first checking into a drying-out clinic seven years earlier that a picture of him drinking was no longer a surprise. But he had been worshipped by a generation of England football fans and, in a celebrity-obsessed age, he could still shift newspapers. Unfortunately, in the years leading up to his arrival in Kettering, it was nearly always for the wrong reasons: drink, drugs, wife-beating, divorce and a whole host of addictions and personality disorders. When he did make the papers for footballing matters, it was normally only because things had gone wrong yet again.

Everybody queuing for their moment with Gascoigne asked him what he was doing in Kettering. He remained polite but evasive.

Just over an hour after walking into the pub, Gardner shepherded Gascoigne back to his car. As they drove away, a pub full of people pressed their noses to the windows or stepped out into the car park to watch them leave.

The pair didn’t have far to go. Kettering Town Football Club is only about 300 yards from The Beeswing, and, as Gardner pulled into the car park that the club shares with the neighbouring bowling alley, the 16-lane Rock ’N’ Bowl, it became obvious why Gascoigne was in town. Kettering, known to their fans as the Poppies, were playing an FA Cup second-qualifying-round match against Stafford Rangers that afternoon, and Gazza was there to watch.

Jon Dunham, the football writer who covered the club for the local paper, had arrived at the ground 90 minutes ahead of kick-off, as was his routine, to be breathlessly told of the celebrity drinking a few hundred yards away. By the time he’d convinced himself it wasn’t a wind-up and dumped his belongings in the press box to make his way back down the stand, Gascoigne was safely ensconced in the club’s boardroom.

Dunham made his way to the social club next to the boardroom, where Gascoigne was the sole topic of conversation among those drinking there, many of whom had wandered along from The Beeswing.

‘What’s he doing here?’ Dunham was asked. ‘Is he going to be our new manager?’

At that stage, Dunham didn’t know any more than the next guy but resolved to find out, although, with a game to cover, he had to wait until the cup tie had finished before he could approach the man himself.

The match took second place to all the fuss that surrounded Gascoigne’s appearance. Prior to kick-off, he had walked up the steps of the main stand to take his seat in the sponsors’ section of the well-worn ground with the eyes of the near-1,000-strong crowd firmly fixed on his back.

By that stage, he had been joined by a sizeable entourage including, among others, Gardner, Gascoigne’s dad John, former Arsenal midfielder Paul Davis and Andy Billingham, whom Gascoigne had met through promotional work with adidas. Off-the-pitch events with Gazza and his cohorts were proving far more watchable than the hard-fought game, which Kettering won 1–0 thanks to a goal from experienced striker Christian Moore.

After the teams had trooped off at the final whistle, Dunham jogged down from the small press box at the top of the stand to wait near the tunnel entrance while Gascoigne exchanged a few pleasantries with Derek Brown, the team’s centre-half and club captain. ‘I stood there thinking, “Why on earth would Paul Gascoigne want to be chatting to non-League footballers,”’ says Dunham. ‘I was thinking to myself, “What’s this all about?”’

The rumour that had swept the ground during the game was that Gascoigne was going to be the club’s new manager. It sounded no less ridiculous each time it was whispered on, but, eventually, Dunham got his chance to ask Gascoigne if there was any truth in it. Gazza smiled at him, shook his hand, signed an autograph and said, ‘No comment.’

Dunham made his way back to the social club believing this was much more than a social visit by the footballing legend, even though the club’s chairman, Peter Mallinger, did his best to pass it off as just that when quizzed.

It was chaotic after the game as hundreds of fans scrambled to get close to Gascoigne. People aged from six to sixty, male and female, hard-core fans and celebrity spotters alike, were eager to talk to him, touch him, get him to autograph their programmes or capture the moment on cameraphones.

Dunham spent a couple of hours digging around to try to find out what Gascoigne was doing there. But he didn’t get anywhere; amid all the speculation and gossip, anyone with any real information on what Gascoigne was doing at the club was not prepared to talk openly. But he did uncover another story: it seemed that not only was Gascoigne interested in becoming the new manager, but he was also looking to buy the club.

Dunham trusted his source but still found it hard to believe that Kettering Town could be of interest to somebody of Gascoigne’s stature in the game. Here was an England legend, capped 57 times for his country, who had played for some of Europe’s top clubs. Kettering Town were so low down the pecking order that they had spent the previous few years in the shadows of Rushden & Diamonds, their despised neighbours a few miles down the road, a club that had been created little more than a decade earlier by Dr Martens mogul Max Griggs.

But a no-comment wasn’t a denial – as any journalist knows, it would have taken just one word to kill the rumour stone dead. So, while Gascoigne returned to the boardroom, Dunham telephoned me, his sports editor, with news of the pandemonium at Rockingham Road.

I put the phone down and smiled. As did the editor, Mark Edwards, when he got his call. Mark and I were big football fans with vivid memories of the excitement Gascoigne had whipped up at World Cups and European Championships. And now Gazza was coming to Kettering? Surely, somebody was having a laugh. But what a cracking story, even if only a rumour. If true, it would be the biggest thing to have happened to the club, which, in its 133 years of unassuming existence, had yet to play in the Football League.

It would also be the biggest story of the young sports writer’s life, and, if nobody, least of all Gascoigne himself, was going to deny that he was on his way to Kettering Town, then this was a story screaming out for 120-point headlines. Front and back pages.

The following morning, I discussed with Dunham and subeditor Jim Lyon how to handle the story for the sports supplement that the Evening Telegraph, one of two regional daily newspapers in Northamptonshire, published each Monday.

Hard facts were still scarce. So as journalists we did what all hacks do when time is short and a good story is in the offing – we telephoned as many people as we could. Few knew anything, even if they struggled to admit it. Those who claimed an insider’s knowledge said they couldn’t possibly give up their secrets, but a couple of well-placed people gave off-the-record briefings that all but confirmed it. Paul Gascoigne, England football genius, was in talks about coming to Kettering Town – although whether it was to be as owner, manager, player-manager or director of football was still unclear.

The story was splashed on the front and back pages. Mike Capps, the club photographer who also supplied the paper with pictures, had been stunned to bump into Gascoigne in the car park. He, too, had been clueless as to why Gascoigne was there but that hadn’t stopped him shooting as many pictures of the superstar as he could. His long lens focused more on the stand than the game, and the pictures were put to good use accompanying the story on the front page, the back page and spreads comprising just about everything that the internet could churn out about Gascoigne in a few hours on a busy Sunday afternoon. It wasn’t all that relevant, but this was Paul Gascoigne. Readers were informed – as if they didn’t know already – that Gascoigne had been forced to apologise to the people of Norway after he had told them to ‘fuck off’, when asked if he had a message for the country ahead of a 1994 World Cup qualifying match. He was only joking, but there were plenty who didn’t share his sense of humour.

They were also reminded that Gascoigne had been forced to say sorry to Glasgow Celtic fans after a provocative flute-playing goal celebration, which he repeated a short time later; that he’d been so angry with then England manager Glenn Hoddle that he smashed up a hotel room; that he’d been in and out of rehabilitation clinics; that he’d gone through an unpleasant divorce after a violently abusive marriage; that he was out getting drunk while his wife was giving birth to his baby son, hundreds of miles away.

There was seemingly no end to it.

And still it seemed so unreal. Why Kettering Town? A club in danger of losing its ground in the very near future. A club meandering along some 130 places lower than his hometown club, Newcastle United. A club of insurance salesmen, postmen and warehouse workers who earned a few bob for playing football on Saturdays, and most Tuesdays as well if they could get the time off work. What was it that had caught Gascoigne’s eye?