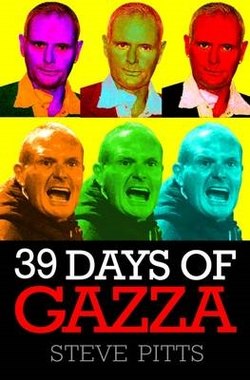

Читать книгу 39 Days of Gazza - When Paul Gascoigne arrived to manage Kettering Town, people lined the streets to greet him. Just 39 days later, Gazza was gone and the club was on it's knees… - Steve Pitts - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

FIT TO BE A MANAGER?

GASCOIGNE’S involvement with Kettering can be traced back to the football ambitions of one man, Imraan Ladak, who had sat anonymously alongside him at the game on that frenetic Saturday in September.

Ladak did nothing to draw attention to himself, as the eyes of the fans were fixed on the man whose dyed blond hair made him easy to pick out from all sides of the ground.

Ladak, originally from Kenya and now living in Milton Keynes, was the chief executive officer of a company supplying locum doctors to the NHS. Still only in his late twenties, he had taken advantage of government deregulation to build up his business to the extent that there was some spare cash burning a hole in his pocket. Ahead of the takeover, The Times had reported that his company, DRC Locums, had an annual turnover of £23 million, with registered accounts showing net assets of nearly £1.9 million. He had also expanded into dry-cleaning.

Ladak, a softly spoken Muslim, had clearly done well for himself and quite fancied the idea of a public profile. By the spring of 2005, he had decided to make a move into football and, having worshipped Gascoigne during his four years at Tottenham Hotspur in the early 1990s, Ladak approached people who knew him. And it seemed Gascoigne, looking for a fresh direction to a life that had turned increasingly sour, was happy to talk. They met at Ladak’s Milton Keynes home that summer and Gascoigne admitted he had been surprised by Ladak’s enthusiasm and knowledge of football. After a three-hour chat, they agreed to work together.

* * *

With a potential future in football to refocus his attention, Gascoigne set about getting himself in shape for the challenges ahead. A couple of weeks after his first appearance at Rockingham Road, he underwent an operation on his neck, the 29th on his battered body.

Before then, he had suffered a career-defining injury at the 1991 FA Cup final in which he tore his cruciate knee ligaments in a suicidal tackle after just 17 minutes. His recovery was delayed when he sustained fresh damage to the joint in a nightclub scuffle in Tyneside a few months later.

In a frank interview with Ian Ridley in The Observer in February 2003, he had confessed that at least four of his injuries were a direct result of drinking. However, according to Gascoigne, this latest operation had not followed an alcohol-fuelled accident; he had been injured in a fall during a practice session for the Christmas ice-skating special of BBC1’s Strictly Come Dancing in December 2004.

That was the end of that particular chapter in Gascoigne’s attempt to maintain a public profile outside a footballing career in terminal decline. And the man himself was well aware that this injury was more serious than any of his broken bones. Many of the fans who had flocked to Gascoigne on his first public appearance in Kettering had asked him if he was going to play for the club. Gascoigne would have loved nothing more but was afraid of the consequences. ‘I’ve had an operation, so for the next few months I’ve got to take it easy,’ he said at his first press conference. ‘I’m scared of another operation. It’s not nice having your throat opened up and have them mess with your spine.’

He was still only 38 years old and the previous few years had seen him desperately trying to make up for all the time spent out of the game through injury. He had turned up at some of the most unlikely of destinations in search of a game, none of which went well. A short spell at Boston United as player-coach in 2004 ended with his playing just five matches before walking away. He initially claimed he was going away to get his coaching badges, but later complained the Lincolnshire club had used his name as a marketing tool.

That had followed an even briefer spell in China with Gansu Tianma. If Gascoigne, who had signed a nine-month contract, had been relieved to get home after just four games and two goals, the Chinese were just as happy to see the back of a man who had fled, without warning, to a specialist clinic in Arizona for treatment for his drink problem and depression.

Although his father and Jimmy Gardner had originally gone with him to China, they returned home after a week, and Gascoigne found the isolation in an alien culture, in which he was struggling to learn the language, driving him increasingly to drink. He complained about the air quality, the heat and the standard of football, but what was clear was that he was desperately unhappy.

The dash from China to America wasn’t the first time Gascoigne had dropped everything to seek treatment for an overwhelming range of disorders. With great candour, he revealed in his autobiography how he suffered from bulimia, obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder, among other conditions.

Even after it was finally confirmed that Gascoigne and Ladak had been in talks to buy Kettering, Gazza continued to attract attention elsewhere. On 18 October, his spokesman was forced to deny he was joining Algarve United in Portugal, with whom he had spent the best part of two months that summer. Ladak, so excited by the proposed takeover he found it hard to keep away from the club, insisted the only reason Gascoigne was absent was out of respect for Kevin Wilson, the team manager, who despite his side’s impressive start to the season, suddenly found himself facing the prospect of losing his job. Jane Morgan Management, who represented Gascoigne, flatly denied he had any intention of signing for the Portuguese club. Gascoigne pointed out that, despite plenty of talk, he was never offered ‘anything concrete’, although Corrado Correggi, the owner of Algarve United, was urging Gascoigne to accept the coaching role he said he had offered him during his brief spell on Portugal’s south coast. ‘In England, there are too many people using him,’ said Correggi.

Gascoigne had been drinking during that summer, not only wine but also spirits, and a drink-related incident at Gatwick airport saw him banned from a BA flight back to the Algarve, bringing him another round of media criticism after he was seen to grapple with two policemen sent to calm him down. As his father and brother returned to Newcastle, Gascoigne set off for the Bedfordshire health farm Champneys, where he often fled when things got too much.

But, even at this haven, he seemed to find it difficult to keep out of the news and he was taken to hospital, although not required to stay overnight, after eating a poisonous berry while out walking in the grounds. ‘I don’t know why you are writing this story,’ a spokeswoman for Gascoigne told the local paper. ‘It was something and nothing. He ate a non-edible berry.’

During this period, Gascoigne went back into hospital to have the follow-up surgery on his neck as a result of his ice-skating fall. Billingham, acting as Gascoigne’s press spokesman, issued a statement saying the timing of the operation had been scheduled so that Gascoigne could ‘be fully fit and focused on his new role’. He also said it had been a success. Gascoigne was only in hospital for two days before returning to Champneys. He was helped with his recovery by the backroom team at Arsenal.

As his health began to improve, Gascoigne continued to look for ways to recover his finances, sadly always suspicious that people were trying to ‘rip off’ his name.

Despite his astonishing earning power in his heyday, he had blown much of his fortune. His personal life had been little short of a disaster and, as a divorced alcoholic who seemed incapable of going too long without a drink, it had taken a heavy toll on his pocket. He was also generous to a fault and had funded houses and holidays, cars and jewellery for family and friends.

He had come to hate the press, believing that what had been printed about him over the previous 20 years had been ‘horrific’ and ‘disgusting’. Despite this, by the time he arrived at Kettering he needed the exposure – and the money – offered by the national newspapers to open his mouth, and his heart, on just about every drama that his life had thrown up.

Eight days after his first appearance in Kettering, in an interview with Anna Kessel in the Observer, he revealed how he had been told his financial situation was precarious. The interview had been granted to help promote his soon-to-be-released Gazza’s Golden Balls DVD, due out before Christmas. ‘He asks incredulously … whether it really takes three days for a cheque to clear,’ Kessel wrote. Gascoigne focused on his ‘props’, two mobile phones, a packet of cheap cigarettes and a large cup of coffee, while Kessel studied the ‘thin and wan’ man sitting in front of her.

As well as carrying out promotional work for the DVD, he revealed plans for a new gadget to make cheaper football boots more effective. ‘I’ve got this thing that goes on the end of a football boot,’ he revealed in an interview to promote the DVD. ‘Instead of people spending a fortune, they can buy a cheaper pair then put this thing on the toe, which helps you curve the ball. It’s going to save families a lot of money.’ At this time, he also confessed that ‘unfortunately these days I don’t get up and just get paid every month. I have to work for a living.’

Perhaps the challenge offered by Ladak had come at just the right time.