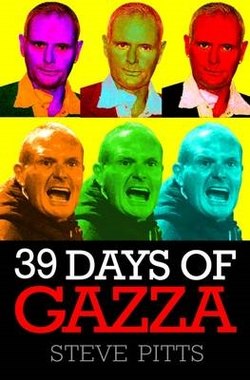

Читать книгу 39 Days of Gazza - When Paul Gascoigne arrived to manage Kettering Town, people lined the streets to greet him. Just 39 days later, Gazza was gone and the club was on it's knees… - Steve Pitts - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I KNOW WHAT THEY’RE SAYING – AND I’LL PROVE THEM WRONG!

ОглавлениеPRESS conferences at Rockingham Road were few and far between. Why would a Conference North club go to the bother of organising a media gathering when a good turnout would be two people, Jon Dunham for the local paper and perhaps somebody from BBC Radio Northampton.

Away from the games, the manager typically met Dunham once a week, normally a Thursday lunchtime, to discuss the forthcoming weekend fixture. But if the manager or chairman, or anybody else for that matter, wanted to impart news or request a plug, it was just as easy to pick up the phone.

If the story on 27 October 2005 had been the departure of Mallinger as chairman and the arrival of Ladak, with Wilson staying on as manager, a press conference would have been pointless. However, the story that day wasn’t merely the change of personnel at a minor-league club. The press had been invited for the unveiling of one of the worst-kept secrets in football: Paul Gascoigne’s first job as a football club manager. And some 70 print journalists, six TV crews and a clutch of radio reporters had squeezed into the social club which had been spruced up for the big event, as there was no other room big enough for such a gathering.

No doubt many of those seasoned journalists making their way to the club would have been cynical both about Gascoigne’s motives and his chances of making a success at a football club so far below his previous level. Plenty of them had seen it all before, having passed on Gazza’s good intentions to their readers as he embarked on yet another venture, only to have to report on the almost inevitable failure a short while later. Nevertheless, this was a man who had given many of them moments to lift them out of their press-box seats, plus some laughs, during his playing days, and there was definitely a certain amount of sympathy and affection for him.

Jon Dunham arrived at his office a mile from the ground and switched on the sports-desk television to see the Sky Sports News 9am headlines reporting live from outside Rockingham Road. The press conference wasn’t scheduled to get under way until 11am, and Sky was doing its best to whip up hysteria in the club’s deserted car park. Dunham began to realise quite how big this story was.

But, had he been in any doubt, the journalist from Rome who had flown in to cover the story for followers of the Serie A club Lazio would have convinced him. More than a decade after Gascoigne’s stint with their team, they still had great fondness for a footballer who may have played only 39 league matches over two years but who had captivated them with moments of sheer brilliance on the pitch, scored a winning goal against hated rivals Roma and made them laugh – even when he was being fined £9,000 for belching into a television microphone when asked how he felt about being dropped.

The start of the press conference was delayed, so the photographers further jockeyed for position and a few more chairs were squeezed in for the late arrivals. The seating order followed a rough pattern of photographers at the front, print journalists behind them, TV cameramen in an arc behind them and TV reporters and radio men hanging around at the back and to the sides, in the hope of securing one-to-one interviews later. It was clearly going to be a long day.

Pressing their noses against the windows was a group of supporters in their dozens who had come along to witness a historic event in their club’s history. With more intimate knowledge of the club than either those who had organised the press conference or those journalists attending it, several sneaked inside to watch from behind the TV cameramen.

Waiting to face the press was Billingham, the self-appointed host for the day, Mallinger, Wilson, Ladak, Gascoigne, Davis and Mick Leech, a Kettering stalwart who was a personal friend of Mallinger. Like the other directors, he was standing down. The new regime was coming in with its own personnel and ideas.

Gascoigne sat down to answer questions from the assembled journalists. He was wearing an open-necked, long-collared shirt that did nothing to hide the prominent white plaster on his neck, which was covering his recent operation scar.

Gascoigne clearly couldn’t wait to get going. In his difficult relationship with the press, he may have found much of what had been written about him to be ‘disgusting’, but he was evidently happy to talk about this new venture. For the first time in a long while, most of the questions were about football and a future in the game. He was positive, upbeat, charming and convincing. There were none of the nervous twitches and afflictions that were to become apparent only a week later.

Gascoigne and Ladak had both prepared statements, and were happy to answer questions before stepping out onto the pitch for more pictures and a series of television, radio and one-to-one newspaper interviews.

Even those who felt Gascoigne was the wrong man at the wrong club seemed to want him to prove them wrong, and they listened attentively as he spoke about a club which had only come to their attention because of his involvement. Davis was to be head coach, Wilson director of football, and Billingham and Ladak the men he was to work with off the pitch to generate the cash for a push into the Football League. ‘This club hasn’t been in the Football League for 133 years so that’s one of our main objectives,’ he said. ‘It’s something for the supporters to look forward to. It’s going to be a big thing for us.’

There was no doubt he believed it was possible, just as he believed he had committed himself to a long-term future at the club. And when he was talking about football he was happy to speak for as long as there was someone to listen to him: ‘I will be spending plenty of time looking at the current squad, working with my assistant manager Paul Davis and Kevin on the strengths and weaknesses of our players and hopefully looking to add some fresh faces where required. We will be working hard to achieve promotion this season. But if not we will regroup and build on the positives of the team to target automatic promotion next season.’

Gascoigne was taking over a team which – under the leadership of Wilson but with an eye on the imminent arrival of their manager-to-be – had gone five games without conceding a goal and had climbed into the Conference North top five. They had also earned a place in the first round proper of the FA Cup.

Things were going so well on the pitch that Wilson, understandably, felt too much change too soon could only be disruptive: ‘I felt it might have been better if I’d stayed as manager and Paul Gascoigne came in as director of football. If they had wanted to bring Paul Davis in they could have done that as coach. That would have kept a bit of continuity.

‘I understood if they decided in the longer term Paul was going to become the manager, all well and good. I just felt it was too sudden, a bit too much of a change too quickly, too many new ideas. With players at non-League level, you have to bring ideas in slowly. Everything was being rushed.’

He also had other concerns. While the focus was naturally almost exclusively on Gascoigne, Wilson sat two seats along from the new manager and was practically squirming in his seat. Of all the places he wanted to be on that Thursday morning, an event being shown live on television was probably the last. He had been unable to make up his mind whether he wanted to be part of the new set-up, forced into a different role which diminished his relationship with the players, and was agonising over whether to walk away.

Adding to his unease, he was off sick with tonsillitis from his day job, and knew it was not going to go down well with his employers at a Northampton roofing company when pictures of him in a suit and tie were beamed into homes up and down the country. ‘I sat there wishing I wasn’t there, feeling like a spare prick at a wedding,’ says Wilson. ‘Everyone I speak to says, “You didn’t look very happy,” and I say, “Would you have liked it if it was happening to you?” I was the manager who had been dethroned.’

Wilson had loved working for Mallinger despite the financial pressures, but felt the role Gascoigne had earmarked for him was little more than an attempt to distance him from the players he had managed over the previous 21 months.

‘They called it director of football but to me it looked like a glorified chief scout,’ says Wilson. ‘He [Gascoigne] didn’t want me in the dressing room, he didn’t want me around the players, he didn’t want me at training. That wasn’t what I had been told initially. I was told by Mr Ladak that I’d be director of football, that I’d be involved in everything, I’d be hands on. My money was going to be the same, but that wasn’t the point. It wasn’t the job for me. I don’t blame Paul Gascoigne for that, it’s one of those situations that happens in football.’

* * *

After the formal press conference had concluded, Jon Dunham took a seat alongside Gascoigne in the small home dug-out in front of the main stand and, with the takeover story in the bag and thousands of words from the new Poppies manager in his notebook from the press conference, set about asking questions that only fans of the club, rather than the public at large, needed answers to.

‘With all the other stuff covered at the press conference, the first thing I wanted to talk to him about was that weekend’s game against Droylsden,’ says Dunham. ‘They were right up there with Kettering and it was a really big game for them. He seemed to enjoy the opportunity to talk as a football manager and we spoke about Droylsden.’

Did he know what he was talking about?

‘To a certain extent he did. He seemed to know a bit about Droylsden.’

Those niche questions had been few and far between when everybody was sitting in the social club a short while earlier. Despite his attempt to look forward, he was still occasionally dragged back to the failures of the past and was keen to point out the differences between his experiences at Boston United, Gansu Tianma and Algarve United and what he was taking on. ‘I was used there for publicity,’ he explained. ‘My name is seen by many as a marketing tool that can create publicity, contacts and ultimately money for their own football club.

‘Kettering Town is a different proposition for me as I’m investing my personal money in return for a substantial stake in the club and a seat on the board of directors. So not only will I be manager working hard to win games for the supporters and everybody concerned with the club, but I will also be a director working hard to achieve the club’s financial goals. My long-term goal is to become a top-class manager and I’m delighted that I am beginning my journey here at Rockingham Road.’

Jon Dunham had been happy to get his 10 minutes with the new manager, and a few pictures of them together, before Gascoigne was dragged away to be quizzed in an endless round of interviews. He had adored Gascoigne the player, but felt up close the new manager did not look quite as well as he had from just a few feet at the formal press conference.

‘Close up he looked frail, he didn’t look like someone who was ready to be a manager at any level,’ said Dunham. ‘He seemed to appreciate talking to me about the players and the next game but he also wanted to be asked about his goal in Euro ’96 and about Italia ’90, and even the darker times with his injuries. He enjoyed the attention completely.’

As Dunham conducted his interview with Gascoigne, the TV crews set up on the pitch and waited for Billingham to grab the star turn and lead him from one microphone to the next. With time on their hands, they interviewed pretty much anybody who would stand still for two minutes.

Ross Patrick was a supporter who had waited outside the social club for two hours before finally talking his way past the stewards on the door. He found himself giving interviews to Sky Sports News, the BBC and ITV and then got to meet Gascoigne, who signed his Poppies shirt: ‘Although he was clearly tired, he gave the supporters his time, which was fantastic.’

As the media kerfuffle finally began to die down, Patrick headed back to the bar, where the former Tottenham and Manchester United striker Garth Crooks, who had interviewed Gascoigne for the following Saturday’s Football Focus programme, was already seated. He bought a round for everybody in the social club and spent 45 minutes chatting to the fans.

Patrick’s day became even more surreal when Ladak popped in and invited him and a friend to be his guests for his first match as chairman. They got to meet Gascoigne ahead of the game, who joked they were in the team and told Patrick he ‘shouldn’t lose a header’.

Peter Short, the matchday programme editor, wrote a column called ‘Shorty says’ in which he explained how the Gascoigne-inspired media attention was having a huge impact on both club and town. There had been a notable increase in the number of Kettering shirts being spotted on the streets and, wherever he went, the football club had become the main topic of conversation: ‘And don’t even get me started on taxi drivers who seem to know everything from what Mr Gascoigne had for dinner to the exact number of column inches that KTFC got in The Times.’

But he did question how long the interest could be sustained at a level unique for a non-League football club: ‘How many more times will I be tuning in to Sky Sports news? How many more times will Mark Pougatch say “Kettering Town” on Radio 5 Live? How many more taxi drivers do I need to have the same conversation with again and again?’ Shorty confessed to having no idea. ‘But I intend to lap up every second,’ he revealed.

Mike Capps had broken off a family holiday in the West Country to return for the press conference. More often than not, when anything happened at Rockingham Road he was the only photographer present. But it wasn’t the case today, and he spent a couple of hours doing his best to ensure he captured every single moment of a dramatic day, and was determined to be the last snapper to leave the ground. As the national press finally departed, Capps found himself sitting alone in the main stand with Gascoigne: ‘He had posed for hundreds of pictures but I asked him if I could take a few more of him with a Kettering shirt. He was happy to do it.

‘I had been introduced to him as the club photographer and I told him that if there was ever anything he didn’t want me to take a picture of to just tell me. He said, “You’ve got your job to do and I’ve got mine. If there’s something I don’t want you to take I’ll tell you soon enough. I’ll shove you out of the way.”’

* * *

Ladak had revealed in his statement that the deal had not been completely finalised and that ‘we expect to have the final paperwork signed before Saturday’s game’. To prevent it from collapsing, Mallinger had agreed to the revised payment plan suggested by Ladak following his failure to get any money off Gascoigne. Gascoigne admitted he had agreed to put up £50,000 but said he did not hand over the cash because, despite repeated requests, he couldn’t get a contract from Ladak.

Although he was not yet the official owner, nothing was going to stop Ladak outlining his plans for a club which he said represented everything that was good about football: ‘Real supporters watching their home-town team because they love football, not glory. Real players in the non-League because they love football, not money. A real stadium with terraces and an atmosphere the players can feel.’

He went on to explain the early priorities were a full-time playing squad, a solution to the stadium issue that had haunted Mallinger as the years on the lease ran down to single figures and building an infrastructure to allow the club to get into the Football League.

And his take on Gascoigne’s appointment? ‘One of England’s finest joining to help fulfil the dreams of supporters and players,’ he insisted. According to Ladak, it was the potential of the club, ‘with possibly the largest fan-base in non-League football’, that had attracted Gascoigne: ‘Paul has been determined to wait for the right club before committing his future and the fact that he is part of this consortium illustrates his confidence in the project.’

However, Gascoigne was already having doubts over his relationship with Ladak, and the lack of a formal contract was a frustration. ‘I saw one once, but then he took it back,’ he later said. He complained of being ‘stitched up’, although at the time of the press conference the lure of a return to football was enough to buy his silence.

Ladak was in a hurry to stamp his mark on the club, and wanted to get cracking. The previous directors might still have been listed among the club officials in the matchday programme for the cup tie against Stevenage Borough on 5 November, but Ladak had told them they had done their bit and it was now time for them to sit back and enjoy the football.

‘My perception was he wanted to run the club his way, which was fine,’ said Dave Dunham. ‘That was his privilege. From a personal point of view, given that he didn’t have any experience of running a football club at all, I probably did wonder if he would benefit from having some help. Imraan was very ambitious and very enthusiastic. I don’t know how much knowledge he had about how non-League football works but I think Imraan would probably say himself that it has been a huge learning curve and he might have done things differently if he could have his time again.’

For Ladak and Gascoigne, however, their lack of knowledge at this level was not something that troubled them. They were both confident in their own ability to get stuck into their ambitious plans, and Gascoigne was quick to establish his hierarchy, making clear that Davis would be his right-hand man while he expected Wilson to look at potential new recruits ‘when we get the money’ and to scout forthcoming opponents. As for himself, he said, ‘I’ll be picking the team and deciding tactics, who comes off, who comes on as sub.’

* * *

Mallinger had watched Gacoigne being chased around the pitch. He had sold the club with a heavy heart and would virtually need to be dragged out of the boardroom. Like Dave Dunham and Wilson, he had been hoping the new regime would not cut all ties with the people who had run the club to that point.

Although Mallinger did stay on to help smooth the transition, he eventually started feeling both left out and squeezed out. Others around the club, who had been appointed by Ladak, would stop their conversations when they saw him approaching, and Mallinger could read the signs. As is his way, he would slip away without fuss, taking a few months out of the game as he concentrated on fighting the leukaemia, and then, as his health improved, buy his way into local rivals Corby Town. He became chairman of the Southern League club and took Wilson with him as manager and Dunham, Leech and Les Manning as directors.

Wilson had left after the press conference and did not join in the fun on the pitch. Despite Ladak praising him in his statement to the media and insisting that he was an ‘integral part of our plans’, Wilson drove home more convinced than ever that his time at Kettering was up.

Wilson handed in his resignation five days later. He had been unsure of the financial situation should he quit, but he had no reason to worry. When he did make the decision to leave, Mallinger would write him out a cheque for the money he was due by virtue of the one-year rolling contract he had signed a few months earlier.

He had watched Gascoigne’s first game as manager two days after the press conference, a 1–0 league win over Droylsden, from the stands, having been told he was not wanted in the dressing room. The victory had lifted the Poppies to fourth in the table and, in those heady days, a genuine push for promotion seemed inevitable.

Gascoigne put Wilson’s nose further out of joint that day by continually talking about ‘my players’, even though Wilson had brought the majority to the club and spent the best part of the previous two years working to improve them, both individually and as a collective unit.

However, it was an incident that happened before the game that really rankled with Wilson: ‘A couple of hours before kick-off I got asked to do an interview with Sky. When I got into the room with them I was told that I was no longer being allowed to do it and that Paul Davis was going to do it instead. Paul Gascoigne had decided that I wasn’t to do it. That was his prerogative, but it was over for me. I came in on the Tuesday and told them it wasn’t for me.’

Wilson said Ladak tried to talk him into staying, while people whose opinion he valued told him not to be hasty. They pointed to Gascoigne’s recent record and told him that, if things didn’t work out, then by staying at the club he’d be the right man in the right place to pick up where he had left off. Despite the excitement Gascoigne’s appointment had generated, there were still those who felt there was every chance that events in Boston, China and Portugal would repeat themselves here. Mallinger and Leech were among those who preached patience, but Wilson wasn’t in the mood to be persuaded otherwise.

His name was rarely mentioned after that by those in charge. Ladak, Gascoigne and Davis had barely got to know the man and their focus was entirely on their big plans. If Wilson didn’t want a part of that, it seemed that was his problem alone.

As for the players, some felt uncomfortable at the way in which Wilson had been squeezed out. But there was little they could do about it and the opportunity to play for such a legend, and the potential for full-time wages, meant they were looking at a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They were quickly learning that they were the envy of the part-time game and there were plenty of players willing to fill their boots if they wanted to follow Wilson out of the door. At this stage, none did.

This was now the club that everyone below Football League level wanted to play for. Ryan-Zico Black was the first signing of the Gascoigne era, joining the club three weeks into the new regime. He was a young, attacking midfielder contracted to Lancaster Town and could barely contain his excitement when he was told Kettering were prepared to pay £10,000 for him. He drove to the ground and then sold himself short in contract negotiations with Ladak because, ‘I was too busy thinking what Gazza would be like.’

Black could not have been happier. He was promised a two-and-a-half-year contract with a basic wage of £20,000 a year that would rise by £5,000 as soon as the playing staff went full-time, which wouldn’t be long. He was told the club wanted promotion that season; the Football League was the goal. He and his girlfriend were put up in a five-star spa hotel, where they ordered room service and champagne. At the age of 25, he had hit the big time. Or so it seemed.

As he sweated in the hotel sauna the next morning, he wasn’t to know of the power struggle that was already simmering between chairman and manager, and how that was to impact on him. Although Gascoigne, who later accused Ladak of being a ‘control freak’, had welcomed Black to the club with a kiss, he felt the player had been forced on him by a chairman who, he was soon to allege, wanted too much say in team affairs. And the players already at the club were convinced Black was the chairman’s signing.

Within days, Black was to find himself at the centre of growing ill feeling between Gascoigne and Ladak. There was also resentment from his new teammates over his salary and contract. His dream move degenerated into a nightmare. Six months and three managers after the excitement of signing to play for his hero, he’d had his fill of pretty much everybody at Rockingham Road other than a few teammates. He would quit to return to his former club, accepting both part-time football and part-time wages as he looked to put six months of bitter disappointment behind him.

Even then, it was to come with a snag that was to cause him further aggravation, despite moving more than 100 miles away.

* * *

Mallinger was able to hand the club over with his head held high. When he had first walked through the doors 12 years earlier, there had been every chance it could go under. Wilson, too, could leave content that he had turned the club’s fortunes around on the pitch, having led them into the Conference North. They were fifth in the table, doing well, and he was handing over to Gascoigne a squad of players who were extremely confident of their ability to mount a serious title challenge. Although he was bitterly upset at being pushed aside, he spoke for most people in the room when he said at the press conference, ‘If Paul turns out to be as good a manager as he was a player, then he is going to be a very good manager.’