Читать книгу Western Herbs for Martial Artists and Contact Athletes - Susan Lynn Peterson - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

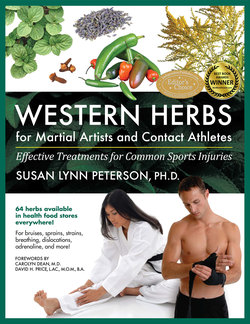

Healing with herbs has long been a tradition in the martial arts. Liniments for bruises, tonics for energy, herbal infusions to strengthen connective tissue, warm muscles, even to heal broken bones—all are part of the martial arts legacy. Most martial artists are aware of that legacy. Not all have access to it first-hand.

It bears saying right here at the beginning of the book that if you do have access to a capable professional martial herbalist, you are most fortunate. Nothing this or any other book can teach you can compare with the hands-on expertise of a medical professional trained in traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Chinese herbal medicine is both more systematic and more comprehensive than Western herbal medicine, and a good Chinese doctor can be a martial artist’s greatest boon. If that medical professional is also your martial arts teacher and can teach you as well as treat you, you are twice blessed. Yet few of us are fortunate to study with teachers who understand and can teach the traditional Chinese formulas. The rest of us pick up what we can, wherever we can. This book is for the rest of us.

The Quandary

In the last fifteen years, books about healing with Eastern herbs and traditional Chinese medicines have begun to be published in English. Though tested by time, these remedies often prove impractical for Western martial artists engaged in self-teaching. Traditional Chinese remedies fit into a larger system of medicine that is very different from the Western tradition of seeing complaints as “one-problem, one-treatment.” Chinese remedies tend to be systemic, treating the entire person to foster health rather than treating a symptom to fix pathology. The ingredients tend to be native to China, some being very difficult to obtain in Europe and North America. Those ingredients that do find their way across the ocean are sometimes of questionable purity.1 Some ingredients mentioned in the traditional books—those made from animal parts (such as bear gallbladder and wingless cockroach), molds and fungi, and various other “exotic” materials—are off-putting to Westerners. Moreover, Western-style medical documentation about the safety of Eastern herbs and medicines is often sketchy. Without a teacher or other formal training in traditional Chinese medicine, many Western martial artists are left with little more than blind trust that the book in front of them is a faithful transmission of a legitimate tradition, and that the herbs they ordered online are, if not what the label says, at least not too toxic.

Western Herbs and this Book

Yet even if you are reluctant to log on to eBay and purchase and brew a packet of herbs from China, that doesn’t mean you must turn your back on the martial tradition of healing with herbs. Though advances in chemistry in the nineteenth century steered Western medicine away from herbal remedies for more than a hundred years, we too have a tradition of healing with herbs. In recent years, that tradition has begun to be folded back into mainstream medicine. A new interest in alternative and complementary medicine has led to studies investigating which herbs do indeed have healing properties. We know more now about the efficacy and dangers of Western herbal medicine than at any other time in history.

The purpose of this book is to investigate those herbs that are readily available to the West. Most of the herbs in this book are either native to Europe and/or North America or have become common in these continents. For each herb I look at evidence for its effectiveness, evidence for its safety, and how specifically to use it. In short, this book is a compilation and distillation of modern evidence for a traditional Western art.

My research is a survey of the various strands of Western herbalism. That research pulls from five main sources:

British herbalism (which had a heavy influence on North American herbalism)

Continental European herbalism (especially from Germany’s Commission E)

Traditional Native American herbalism

Folk uses in Europe and North America

Standard scientific research from around the world (especially the United States)

It is a combination of tradition and new research, practical experience and scientific method, and it pulls from literally hundreds of sources in an attempt to get the “big picture” for any given herb.

Among the references regularly cited are these:

The 1918 U.S. Dispensatory. This volume is the twentieth edition of a reference book used mainly by pharmacists back when you could still get an herbal remedy made up for you by your local pharmacist. It is the last of the dispensatories to deal in depth with herbal medicine, and it represents the best science of its time.

“The Eclectic School” was a branch of American medicine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This school believed in merging traditional herbalism with other treatment methods. Eclectic physicians reserved the right to choose whatever methods most benefited their patients, hence the name “eclectic” from the Greek eklego, meaning “to choose from.” The last Eclectic medical school closed in Cincinnati in 1939. Two authors have passed down to us the knowledge of the Eclectic School. Harvey Wickes Felter authored The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. And John William Fyfe, a teaching physician in New York, authored three manuals for physicians detailing how herbs can be used to treat specific conditions. They are The Essentials of Modern Materia Medica and Therapeutics (a.k.a. Fyfe’s Materia Medica), Pocket Essentials of Modern Materia Medica and Therapeutics, and Specific Diagnosis and Specific Medication.

Commission E monographs. The Commission E monographs are analyses of various herbs, commissioned by the German government to assist in the national regulation of herbs. These monographs, written by health professionals are sometimes detailed and carefully reasoned. They sometimes read like “medicine by committee.” But they do reflect a modern take on traditional European herbalism.

The PDR for Herbal Medicine. The herbal counterpart to the Physicians Desk Reference, it is a reference book for modern mainstream physicians. It contains information on therapeutic properties and drug interactions.

The Modern Herbal. The Modern Herbal, despite its name, isn’t modern. The edition cited here was published in 1931 by Maud Grieve, president of the British Guild of Herb Growers. She was one of the leading experts in British traditional and folklore uses of herbs during and after World War I.

The Purpose of this Book

It is not my intent here to investigate every possible use of every herb, but to focus on those herbs that may be of particular use to martial artists. I look at herbs that may help with bruises, scrapes, and cuts, sprains, muscle strains, and breaks and dislocations. I look at those that help with breathing. I look at those that deal with management of “adrenaline” and other products of the fight-or-flight system such as anxiety and insomnia. And I look at a couple of minor issues that tend to plague martial artists: battered feet, skin chafed from gear, plantar warts, jock itch, athlete’s foot, and for those who commonly kick or grapple after supper, flatulence.

Those familiar with Eastern herbs will see a couple of large gaps. I don’t deal with herbs for conditioning of hands and feet or herbs for regulation of qi before or after martial injury. Why? Western medicine has no equivalent for these uses. The typical Westerner has no need to condition hands. As for qi, because its very existence is questioned by Western doctors, it’s not likely to pop up in Western clinical trials. I omit these topics not because they are unimportant. I omit them because of a complete lack of available Western information about them.

Apart from those particular gaps, the research here is eclectic and wide-ranging. I have investigated insights from Europeans, North Americans, and Native Americans about what has worked for their people throughout the centuries. But I’ve also gone digging into the research: clinical trials, animal trials, and chemical analyses. I’ve gone looking for herbs that would impress not just the grandmother who learned herbal lore from her mother, but also the granddaughter training in modern biochemistry.

As for precautions, this book is full of them. Though I believe in boldness, I also believe there is another name for a beginner who would charge boldly into great risk for small reward. That other name is “fool.” This herbal is a beginner’s guide. It is written for people who don’t have enough experience to give them instincts about which herb uses are safe and which are not. For that reason, I’ve included even the most conservative cautions postulated for each herb. Some trained herbalists will scoff at some of them. I include them anyway, so the beginners reading this book may have as long a view as possible of the herbal landscape and its potential dangers.

The goal is to give the martial artist enough information to make an informed choice about which Western herbs to experiment with. In terms of “acceptable risk,” there are those herbs that nobody should use, those that only expert herbalists should use, those that only people with a high tolerance for risk should use, and those that just about anyone can use. The goal is to help you sort out which is which. On the other hand, there are herbs that scientific studies, herbalists, and medical doctors all agree work; herbs that only traditional herbalists acknowledge; and herbs that your Cousin Phil used once and now swears by. Again the goal is to help you sort out which is which. If you can come away from this book with a clear preliminary risk–benefit analysis for an herb that may meet a training need, the book will have met one of its main goals.

A word about my credentials and philosophy in using herbs: First of all, I am not an herbalist; I’m a researcher. My educational background, my work experience, and my writing for the last twenty years has trained me to sift through mountains of information, to pull out the useful bits, and to present them in a way that’s clear and immediately useful. That’s what I’ve tried to do here. This book rests not on my own personal ability to prescribe or use herbs, but on my ability to seek out the best of the best among those people who do. That’s why the book is heavily endnoted, so you can follow the trail of my research, dig deeper if you’d like, and draw your own conclusions. Most of all, I’m not telling you what you should use; I’m telling you what I have discovered about these herbs. If you chose to use any of the herbs presented in this book, it is your responsibility to go beyond my research until you yourself are convinced of the safety and efficacy of the herb you are using. It’s for that purpose that I have documented my sources and offered resources for further investigation. Any time you take a drug, supplement, or botanical, you must remember this: it is your body, your choice, your responsibility to bear the consequences. I wish you wise choices.

Throughout the book I use my own grading scale from zero, and one to five. One is “somebody, somewhere thought the herb might be useful.” Five is “pretty much everybody, traditionalists and Western scientists alike, thinks it’s useful.” Here are the criteria I used:

Universally recognized by both conventional medicine and alternative medicine as being a safe, reliable remedy. Large–scale clinical tests say this herb works. This level is the “holy grail” of herbal medicine. Few if any herbs or dietary supplements gain this kind of recognition. No remedy is a sure thing, of course, but this one has far fewer documented risks and far more documented success than the vast majority.

Recognized by several scientific studies as well as by ample tradition as being a reliable remedy. This herb is well on its way toward gaining the recognition of both conventional and alternative medicine. We are also beginning to get a firm handle on the associated risks. Only a small handful of herbs have gained this level of recognition. No remedy is a sure thing, of course, but this one has more documented success than most.

Research combined with traditional evidence is promising, but more results are required to draw definitive conclusions. Some studies show that the herb might be an effective remedy. Either these studies are solely on animals, are unduplicated, or are not up to the highest standards of research; or they test not the herb but only one active ingredient of the herb. Generally, research into the herb’s safety is similarly sketchy. A worthy experiment, but with some risks.

We have confirmation by more than one source of this herb’s usefulness. Perhaps scientific research is unavailable, but anecdotal evidence is good. This herb has been used to treat this particular condition either throughout centuries or by at least two independent cultures. Or scientific research is preliminary, substandard, or contradictory but it agrees with some minimal anecdotal evidence. The herb might be worth an experiment, but with unknown risks.

Minimal evidence. Some anecdotal or hearsay evidence says the herb might be useful in treating this condition. We have, however, no clear pattern to usage between cultures or throughout time. If you experiment with this herb, there are no guarantees regarding efficacy, risk, or safety. Proceed with caution and a bit of skepticism.

Multiple tests indicate either that the herb does not work for this condition, or tests indicate that the herb does more harm than good for this use. Don’t use this herb at all for this use without the guidance of a trained naturopath, herbalist, or savvy physician.