Читать книгу Phantom Ships - Susan Ouriou - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеAs of 1653, Nicolas Denys, nicknamed Grande Barbe, received from the Compagnie de Nouvelle France (established by Richelieu) a vast concession stretching from Canseau to the Baye des Chaleurs in Acadia. He organized the triple trade of lumber, fur, and fishing there with establishments in, among others, Miscou, Nipisiguit, and Miramichi. He was appointed governor of the territory and given the mission of settling eighty families there.

– The author

Five months had passed since Joseph’s arrival in Ruisseau. The hot season was not yet over, and it was already time to begin preparations for winter. But the most urgent task was finding shelter since the newlyweds did not want to spend the winter in a tent. Joseph and Saint-Jean put the tribe to work digging a cellar, a lesson learned early in the colony’s life when the first arrivals froze royally. Cedar trees grew abundantly in the wetlands upstream of Ruisseau, and Saint-Jean had cut several cords of cedar the preceding winter. The Mi’kmaq began squaring the wood with an axe from New England that was thicker and heavier than the trading axes manufactured in France. Notches were cut into the logs so they fit one on top of the other to form the walls. Pegs made of maple or larchwood helped reinforce the construction. The rest – the crossbeams and joists – was made of eastern white pine. White birchbark between the walls served to keep out the wind. In no time at all, the tribe had erected a one-room cabin measuring approximately fifteen feet by twenty-five. Little Membertou used his hatchet to chop off any knots that jutted out. Since the cabin was no Château de Versailles, the boy was allowed a few mistakes. Angélique and the women prepared the moss and clay to caulk the frame, while the rest of the tribe assembled embankments of dried seaweed to a height of approximately one foot to insulate the foundation properly. Finally, the sloping roof was covered with moss. With a stonecarver’s enthusiasm, Joseph tackled building the hearth, a fireplace to be used for cooking, lighting, and heating purposes, although it mostly heated the great outdoors! He was euphoric as he worked, already imagining how, on nights when snow gently fell to the ground outside, he would be able to warm himself sitting on his bed of fur in front of the fire – the crackling wood knots, the scent of maple logs, the dancing sparks, and Angéliques gentle presence.

That fall the camp was invaded by mosquitoes. Joseph had to keep feeding the grass fire he’d lit in a metal barrel in his cabin; compared to mosquito bites, smoke was the lesser of two evils. Joseph was impressed by the Mi’kmaq spirit of ingenuity; for every problem there was a solution, for every season there was a form of entertainment. During the hot season, they built a sweat lodge. In a tent lying low to the ground, the Mi’kmaq arranged heated rocks in a circle in the centre, which were then covered with spruce leaves and sprinkled with a bit of cold water. Afterwards, the Mi’kmaq sat naked, shoulders touching, in a tight circle around the rocks. Sometimes, to feel the heat even more, they sang and tapped their heels. Then they ran outside and threw themselves into the creek. It was a ritual with therapeutic virtues since it facilitated the cleansing of the body.

But this was no time to dwell on fond memories of the good times in the hot season because there was still much that had to be done before winter set in: wood to cut, hay to gather, crops to store away, fish and meat to be smoked and cured. Nothing could be neglected when everything had to be produced. Angélique prepared the flax with which she would make clothes, a lengthy operation that involved drying, crushing, carding, and spinning the flax. She also prepared the furs; she liked the beaver hides that she sewed together to make clothes or blankets. She still had to make soap; pick blueberries, wild strawberries, and raspberries; and bake apples. The work was exhausting, but she wouldn’t have traded places with anyone. She soon forgot the long days once she was curled up in Joseph’s arms, and the two of them drifted off to sleep in the warmth of their cabin.

The Mi’kmaq were more a trapping than a farming people, and therefore more nomadic than sedentary. But Angélique had insisted that next to the creek the clan clear a plot of land on which to raise a few oxen, sheep, hens, and one cow and to cultivate a small garden that produced turnips, squash, beans, corn, and other delicious vegetables for their table.

Saint-Jean had little to do with the farmwork. His passion was trapping, furs, and the forest. So he laid traps and, of course, kept up his weekly treks to his refuge on the island. Each week, he made the league-long trip in his sailboat. One fine morning that Indian summer, he invited Joseph along. At first, they said nothing. Finally, Saint-Jean confided, “Before I left France from the port of La Rochelle, I had to spend several months hiding out on the Ile de Ré nearby. The island’s inhabitants saved my life. Since then, I’ve always wanted to have my own island, a sanctuary where I can rest and forget about the men who were on the galleys with me. I’ve built a fine observation tower there.”

He had created a hideout at the western end of the island, at the top of a triangle formed by three huge spruce trees.

“What a wonderful view!” Joseph exclaimed.

They could see for great distances. The Gaspé coast was visible across the way as were, at the entrance to the Baye des Chaleurs, the Chipagan1 and Miscou islands.

“Cartier pinned his hopes on Miscou. He thought he would find a passage on the other side leading to the sought-after Indies,” Saint-Jean said. “He believed so fervently that when he rounded the northwest point of Miscou, he named the point Cap de l’Espérance, Cape of Good Hope. As a sentinel guarding the entrance to the continent, the island has been witness, and sometimes even home, to many flags: Viking, Basque, French, English, Spanish, and Dutch as well as to pirates and buccaneers who, from the tales that are told, would stop off there to bury their loot and treasure.”

Near the Mi’kmaq camp farther down the coast was a small island the Mi’kmaq called Pokesudie; it was a sacred site sometimes used for religious ceremonies.

“I often come to my hideout to sit and smoke my pipe… I watch the European ships sailing by. It’s too late this year for the English fleet and the privateers: the frost is coming. You won’t have to go to Quebec.”

Deep down, Joseph was relieved. As much as he hoped for news of Emilie, he dreaded it, too. Sometimes, he wished he could close that chapter of his life and have done with it because he was happy with Angélique. She offered everything a man could ever want – beauty, warmth, generosity, intelligence, sensuality. Saint-Jean had lit his pipe and was reliving the past. “I’ve come a long way since my days on the galleys!”

He remembered his early years in Miramichi fur trading for the Comte de St. Pierre, who held trading rights between Ile Saint-Jean2 and Miscou. He was on board the Count’s ship that ran aground in the Caraquet region in 1723. The Count hadn’t taken the loss of his furs well. Out of disgust with the Count’s temper, Saint-Jean decided to settle down in Ruisseau… and work for himself.

Having reminisced enough, he turned to Joseph and said, “Some day I dream I will see along these coasts houses full of people, busy villages, tradespeople: carpenters, blacksmiths, locksmiths, ferriers, tailors, shoemakers…

Joseph let himself be caught up in Saint-Jeans dream. “I think I can see husbandmen and vintners, too. I can hear seamen outfitting the ships.”

“There will be goldsmiths, apothecaries, fishermen, barbers…” Saint-Jean continued.

“Men of the church,” Joseph added.

“Not them,” Saint-Jean exclaimed, irritated. “They ruin it all. The Indian customs are good enough for us.”

Joseph understood the bitterness expressed by Saint-Jean, still hurting from past scars.

“I dont want any arquebusiers or gunners either,” Saint-Jean continued, “but I’m afraid for the future. France isn’t looking after us properly, and the most enterprising French who want to come to America, the Huguenots, have to settle in the colonies of Virginia, Boston, and Delaware. One fine day, the colonies won’t put up with having a foreign empire on their doorstep anymore.”

“But Pierre du Gua, one of Acadia’s founders, was Protestant,” Joseph pointed out.

“That’s true, but that was a long time ago. I’ve even heard that Champlain had similar sympathies. But we won’t change either the past or the politics of France.”

Joseph could only concur with the wisdom expressed. Perched atop the spruce trees, the two men seemed as though suspended in time. After a lengthy pause, Joseph spoke. “Where does the word ‘Kalaket’ come from?”

“It’s a Mi’kmaq word meaning ‘at the mouth of two rivers.’ The rivers run west of the creek named after me. But there’s something peculiar about that word. The Normans who fish nearby on the Banc des Orphelins sail on big low-draft ships called calanques.’ During storms, they seek shelter at the mouth of the two rivers… It’s not a huge leap from calanque’ to ‘Kalaket,’ perhaps that’s what the Mi’kmaq did.”

Silence again. As though in cycles: a few words, then a moment’s truce to fully appreciate the serenity of the surroundings. Saint-Jean broke the silence, “Can you keep a secret? I have a hiding place that no one knows about. For years I’ve been stockpiling dried food, flour, and wine in a cave. I keep weapons and powder there too, in the event of a siege. If ever there’s a raid along our coast, we could hide out there with Angélique and the children.”

The word “children” reminded Joseph he had news for the old man. “Angélique is expecting,” he whispered.

Saint-Jean wept tears of happiness.

* * *

Indian summer was drawing to a close. Opening his eyes one fine morning, Joseph realized that something was missing: all of a sudden, he felt horribly homesick. He thought of his mother, Quebec, the animated docks, the streets, the taverns, the meals with neighbours, and the great ships arriving from Europe and the West Indies.

Joseph spent all that day wandering through the camp, irritated by the sounds, the images, and the smells of Mi’kmaq life. He could no longer see the beauty and harmony, only ugliness and disorder and superstitions, like the one obliging menstruating women to keep to themselves in front of a tent. Nearby, a bear meat and fat concoction boiled in a pot: the meat had hung for too long, it was covered in hair and black from excessive cooking. The women ate greedily straight from the pot, wiping their fingers on the coats of the dogs that waited for scraps. The boiled beans doused with grease made him feel like vomiting.

Foaming Bear, who wanted Joseph as an ally, invited him into his hut – a large round, poorly vented tent that was full of smoke and too low to stand up in. Inside, some twenty people were seated by age and social rank, with the women next to the door to look after the chores! Strips of dried meat hung here and there, and the dogs roamed freely among the clay jars full of corn flour. An old man was eating his lice, not out of desire but to take his revenge on the lice. A horrific stench assailed Joseph’s nostrils, chasing him away, back to Quebec, to his world, to his friends, to Emilie’s perfume. At the risk of offending Foaming Bear, he slipped out. He headed toward the beach, to look for comfort by the sea.

On the beach, several women were sewing hides and birchbark to a pole structure. They were using pine roots as thread and sharpened bones as needles. Joseph was oblivious to their ingenuity, their hospitality and their respect for nature. He had forgotten that hygiene was just as bad in Quebec and that, actually, the stench was even more tenacious there: the stench of corruption given off by certain leaders, and the stench of superstitions and religious intolerance no amount of incense could mask. When he returned home in the same foul mood, Angélique asked, “What’s bothering you?”

He hesitated, not wanting to hurt her feelings. “It’s too quiet here. I miss Quebec.”

Angélique was not at all surprised; she was accustomed to seeing many comings and goings in her tribe. “Why don’t you build a schooner and go off on an adventure, starting with Quebec?” she suggested.

“That sounds like a very good idea. But I don’t know if I can build a boat.”

“You’ll be able to with my father’s help; he’s had experience with shipbuilding.”

He was genuinely pleased at the idea and let himself be won over by her suggestion. “We could sell our furs in Quebec for a profit, take merchants the oysters that have been piling up at Pointe-de-Roche3, come back with tools, fabric, apples, cider. What a wonderful idea! Why didn’t I think of it myself?”

He knew why; he was well aware that fear paralyzed him, a fear stronger than his desire to find out the truth about Emilie. It might affect my happiness with Angélique, he thought.

Guessing at the direction his thoughts had taken, Angélique said, “No matter how hard you try to hide it, I know she’s still on your mind.”

He had to confess there was some truth to her observation. “But that’s only normal, after all. I don’t know what has become of her; the mystery haunts me… But don’t worry, I’m happy with you, and I have no intention of running away.”

* * *

One fine November morning, Joseph saw a ball of fire racing across the sea off the island, changing its speed, shape, and direction as it went. Inside the fireball was a jet-black ship with large white sails and, on its bridge, seamen running.

“The phantom ship!” Saint-Jean exclaimed. “Well have bad weather tomorrow.”

“What is it?” Joseph asked.

“No one really knows; the closer you get, the farther away it moves. They say it’s a phantom ship that belonged to a Portuguese explorer and that the Indians burned in revenge for a raid on their shores.”

The weather was indeed terrible the next day. Northwesters raged furiously, making the trees facing the cape twist and groan; at one point, it seemed like the camp would take to the air. The next morning the shore reappeared, strewn with debris and flotsam. Lobsters and crabs clung to the tall grass along the shore. This manna from heaven meant Angélique was able to put up all the supplies needed for winter; the surplus would be used to fertilize the earth.

The winter promised to be fierce. Around late November, a huge white sheet blanketed the frozen bay in lacey creases. The sky looked as though it had been punched through with holes. Joseph and Angélique were at their happiest when storms raged over the Baye des Chaleurs. Stretched out on his bed of furs in front of the hearth, where embers burned under the ashes, and with the scent of Angélique in the air, Joseph felt a wave of serenity wash over him.

Angélique examined Joseph’s lithe body. There was something she had often noticed – at the smithy, in the sweat lodge, as he built their house, or as they caressed each other outdoors or by the fire – on his chest above his heart, Joseph bore a skilfully wrought tattoo.

“I left Nantes in 1717 when I was two. My nursemaid died during the crossing… The tattoo must be an indication of my origins. I’ve always wondered about it, and I hate riddles…”

“It looks like a coat of arms, like the ones the nobles have. I’ve often thought you must be the bastard son of a king or prince,” she said laughing.

“My parents must have been wealthy. When I arrived in Canada, a carefully wrapped violin was found in the trunks. Not just any violin either – a Stradivarius.”

“Perfect, you’ll be able to celebrate with a tune,” Angélique murmured. “Because our baby in my womb is in a hurry to be born; I can feel it kicking.”

Joseph laid his hand on the mound of Angélique’s belly, which rippled with the stirrings of life.

“If it’s a girl, we’ll call her Geneviève,” Angélique suggested.

“And if it’s a boy, we’ll baptize him René-Gabriel in your father’s honor.”

The cabin groaned as an especially strong gust of wind punctuated Joseph’s wish.

“The weather doesn’t get this bad in Quebec,” Joseph complained.

“This is unusual. We expected a bad winter though, because of how high the bees built their hives in the trees. But it won’t last; there’ll be a lull in January, and we’ll be able to go on the trapline.”

“Do you trap the same animals found around Quebec?”

“I think so: mink, ermine, marten, red fox, muskrat, but mostly beaver. It pays, too. Before, the French – some of them anyway – gave worthless objects in exchange for our furs: mirrors, necklaces, alcohol to get the Indians drunk before robbing them. But ever since my father started looking after the trade, they’ve had to pay us with weapons, munitions, tools, fabric…”

Angélique spoke with feeling, proud to have a father who knew how to stand up for himself.

* * *

In February, Joseph went with Saint-Jean to the woods to choose two white pines for his schooner’s masts. Before chopping them down, they waited for the waning phase of the moon, when the sap barely runs. Joseph spent the winter in a state of euphoria, revising almost daily his plans and calculations for his ship. His joy was all the greater with the swelling of Angéliques belly and the approaching birth.

In Aprils budding season, Geneviève was born, a rosy bundle of life like a dancing electrical storm off Pointe-de-Roche. That same evening, while the baby slept soundly, Joseph played his violin. In the melting snow, he danced on and on along the cliffs; he hadn’t danced like this since Emilie had left him, a wild, crazy, exuberant dance, which led him to believe that in another time and place, someone in his family must have had a dancer’s gift. Joseph was happy – a little girl for him, for Angélique, for the two of them. As for Membertou, he was a bit hesitant and jealous at first because of all the attention being lavished on the baby, but it didn’t take long before he started helping his mother look after Geneviève.

In May, Saint-Jean traded furs with merchants from La Rochelle in exchange for ironwork, oakum, sails, pitch, Riga hemp, and other invaluable building material. They also took advantage of the opportunity to stock up on rum from Martinique, which made the work go by more agreeably. Saint-Jean already had a store of wood: logs had been soaking for a long time in a ditch at the mouth of Saint-Jean Creek since the sea water there made them exceptionally resistant. Pinewood for the bridge, oak and beechwood for the ribs, gunwales, and yards, and hemlock for the keel. He laid the wood out to dry for part of the summer and, by the fall of 1741, the schooner was beginning to take shape. This was Joseph’s first boat, but he had spent so much time watching the shipbuilders in Quebec at the Cul-de-Sac shipyard that he felt capable of building a three-decker warship. What’s more, his partner was an old hand. During his stay in convict prison, Saint-Jean had spent a great deal of time repairing galleys. Moreover, the Mi’kmaq were happy and eager to help. They showed them how to use the tools and do the caulking and the tarring. The sight of his two-master measuring sixty-two feet long from stem to stern and eighteen feet wide, with a draw of eleven feet, two decks, and a castle fore and aft, made Joseph feel as free as the cormorants that plied the bay.

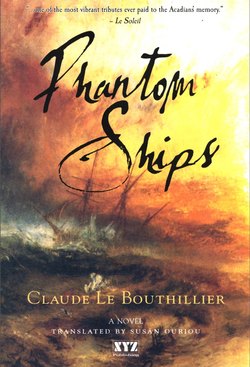

The travel demon bit him, infecting him with a thirst for adventure. Excited by the prospect of setting out onto the high seas like his childhood hero Sinbad the Sailor, he baptized his ship the Phantom Ship. To the prow, he added the carved dragon that had decorated the Viking drakkar run aground not far off Miscou.