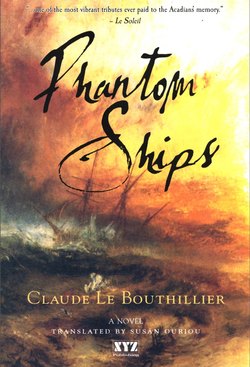

Читать книгу Phantom Ships - Susan Ouriou - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеOn October 31, 1603, the French admiral Montmorency delivered a commission to Pierre du Gua, Sieur de Monts, a Protestant gentleman of the court of France. The commission, a vice-admiralty commission, covered “all the maritime Seas, Coasts, Islands, Harbours & lands found near the said province and region of Lacadie… and “the lands he shall discover and inhabit henceforth.”

… In making him the King’s lieutenant-governor on November 8, Henry IV bestowed on him authority to grant seigneuries for all lands located between the 46th and the 40th parallel as well as a ten-year monopoly over trading with the savages on the Atlantic coast, in the Gaspé peninsula, and along both shores of the St. Lawrence River… lastly, in the first year, he will be responsible for transporting to Acadia one hundred people, including any vagabonds he is able to conscript.

– Marcel Trudel, Histoire de la Nouvelle France, Le comptoir, 1604–1627

Joseph settled into a simple existence in a small hut in the camp at the point where the Saint-Jean Creek – Ruisseau – flowed into the sea. As a man of action used to making decisions without hesitation, he had no intention of remaining inactive while waiting for a hypothetical English fleet. So he restarted the small smithy that Saint-Jean had neglected in order to focus on the fur trade. It was as though the fire from the smithy was the only thing that could compensate for the pain of losing Emilie, the hammer on the anvil giving birth to objects born of his pain. The bellows fired up the embers, sparks danced with each blow of the hammer on the red-hot rods, incandescent metal was dropped hissing into cold water to be cleansed, all to the accompaniment of Joseph’s laboured breathing and the sweat trickling down his body. Hatchets, irons, nails, arrow tips, hardware, and even horseshoes piled up, for he knew one day there would be horses in Ruisseau.

He did not notice her until the third day. She was slender, bare of torso, dark, proudly wearing a wampum necklace – beads of seashells on a string used both as currency and symbolic decoration. Her necklace drew attention to her breasts. She wore a skirt cinched tight at the waist by an embroidered belt studded with loon feathers. Her earrings were carved out of golden seashells. The magnificent young woman was Angélique, Saint-Jeans daughter. Her mother, a Mi’kmaq who had taken the very French name of Madeleine, had been married to the Norman captain Alfred Roussi of Rouen. A daughter, Françoise, now living in Gaspeg, was born of that first marriage. On her husband’s death, Madeleine married Gabriel Giraud, known as Saint-Jean. Angélique had never known Madeleine because she was only a year old when her mother died giving birth to her brother Jean-Baptiste. Angélique imagined her mother through her father’s words, then carried on the family tradition by developing her own talent with medicinal herbs and learning the midwife’s art herself.

This was Joseph’s first contact with native customs. I would never see half-naked young women like this in ob-soCatholic Quebec, even less so in Notre-Dame-Des-Victoires Church. Not women of such innocence and purity. My God, she is beautiful!

Lost for words, he couldn’t tear his gaze away. How can an Indian – Métis or no – have such long golden hair to her waist? he wondered, noting she was even more blonde than her father. Her hybrid beauty fascinated him.

Every day, Angélique came and sat at the entrance to the smithy, mesmerized by the tall, taciturn, bearded man who struck the anvil so furiously. By the seventh day, Joseph and Angélique still had exchanged only a few words. That day, after bringing him a drink of sugar, ginger, and cold water, Angélique decided to break the silence. “Why did you come here?” she asked.

“I was supposed to go to work on the Louisbourg fortifications, but I have to stay here until the water freezes over to warn the Quebec garrison if the British come up the river,” Joseph replied.

“The never-ending wars. I don’t understand your Christian principles one bit.”

“Believe it or not, I have a hard time understanding them myself,” Joseph confessed with a hint of irony.

Not satisfied with his brief response, Angélique insisted, “Why did you leave Quebec?”

Joseph decided to confide in her, “During a trapping expedition out by the St. Maurice1 smithies, where cannons are manufactured for the Quebec fortress, I was badly hurt and the Algonquins cared for me. I spent the winter half-delirious and amnesiac. By spring, when I returned to Quebec, my fiancée had taken me for dead, and left. I tried to find her but in vain. Emilie had flown off to other climes. Louisiana, the West Indies, Europe?… So I decided to leave and make a new life elsewhere…”

Angélique said nothing, but her expression showed she wished she could comfort him, rub salve on the wound. “You’ll forget,” she finally said.

Joseph thought he heard, “I’ll help you forget…” He, too, had questions he was dying to ask.

“How is it that you re so blonde?” he ventured at last.

“They say that shortly before the French came here, a strange boat with a carved prow appeared off Miscou; they were Vikings come from a great island in the North, an island with volcanoes and geysers. The Mi’kmaq welcomed them like lost gods, and bonds of affection were woven between our two peoples on beds of moss. As you can see, they left their traces!” she said with pride. “There are many other legends… When the moon rises, the southwester breeze murmurs that Jacques Cartier was welcomed in Ruisseau by the chief of the Mi’kmaq, who offered him his daughter as a token of his friendship.”

“If the rumour is true, then an explorer’s trade doesn’t just involve planting crosses!” Joseph exclaimed.

Although Angélique spoke French, her voice held the intonations characteristic of the Mi’kmaq language, which sounded sweet to Joseph’s ears.

“But my son has no European features.”

Joseph had trouble imagining her as a mother. “You have a son? But you seem so young!”

“I had a baby when I was sixteen. His father died over two years ago, carried away by one of the white man’s diseases. I didn’t turn to the forge to forget my pain, though, I turned to plants, herbs, and flowers.”

A seagull soared overhead, clouds filled the sky, time slowed to a languorous pace. Time for pleasure. His deep-seated fascination with this woman seemed to show the way to a new life.

Day after day at the fiery forge2, Joseph exorcized his pain and sense of loss by striking the anvil again and again. On the tenth day, his rage surfaced. The forge blazed, resembling the hell shown in the missionaries’ pictures. After all, she could have left behind a letter, a note, a word, a message, to explain her actions… Contacted my family… Unless she had something to hide, unless she left with another man… Will I ever see her again? Will I ever get to the bottom of this? he wondered furiously.

Another wave of anger engulfed him at the thought that Emilie could have betrayed him, that she might be honeymooning somewhere right now. Angélique had been watching him and was forced to take a step back as the flames took on apocalyptic proportions.

On the fourteenth day, it seemed to Joseph that Angélique’s bared breasts were in the way of an offering. Saint-Jean watched their little dance with amusement. Membertou, Angélique’s son, had started to sulk. Although Joseph slid under the beaver pelts every night, he did not need them for warmth. By the second week after his arrival, his entire being, like the forge, was a bed of glowing embers.

* * *

All night long, the tribe celebrated along the shores of the Poquemouche, which looked like a raging river in places. By resin torches that lit up the night, the natives used their fish spears resembling tridents to harpoon eels and throw them in with the other eels squirming in baskets. Joseph was introduced to the sport. Angélique served as his guide. He was bewitched by the woman, by her powerful magnetism. He felt a growing passion as the stars danced in the sky and the moon disappeared. As the sun rose, he felt as though even the leaves on the trees had begun intertwining. But he couldn’t quell a feeling of unease. Not brought about by the memory of Emilie, but by the thought of Angélique, her origins, and the child who was not his. And yet… Angélique symbolized the vitality of this continent steeped in the humus of its First Nations and its forty centuries of history. Born through her mother of a people that had incarnated the age of Enlightenment well before Louis XIV, when Europeans were massacring the Infidels to conquer Jerusalem in the name of the love of Christ, she was a breath of fresh air and mystery that he longed to touch.

“Come, I want to show you a quiet creek where I go to to be alone,” she whispered.

She held out her hand to help him out of the canoe; he thrilled at her touch. He was torn between two passions: one inaccessible, the other near at hand… They sat together in a small moss-covered clearing under the shade of two giant birch trees. Angélique offered him some smoked salmon and wild strawberries she had brought with her. The intimate feast ended with fresh spring water after which he fell asleep. He woke to Angélique’s eyes on him. Joseph stared back intently, as though her beauty might evaporate.

“I had a dream while you were sleeping,” she confessed.

“About what?”

“You were lying dead on a bed of moss. You looked so fine, all surrounded by light.”

“What does the dream mean?” Joseph asked, surprised.

“For us, it represents a sort of resurrection.”

“Resurrection? Well, what do you know! That’s what it would take for me to believe what I’m feeling right now,” he thought out loud.

He knew the importance of dreams to her people. Her words gave him the courage to take her into his arms. He breathed in deeply. Time, space, and memory, like the sun overhead at its zenith, came to a halt. Mountains of clouds took shape, then vanished. The forest, the river, the creek all came alive. Slowly, his heart pounding, Joseph began to caress Angélique, who whispered her desire. Swiftly, Angélique shed her clothing. As they made love, Joseph felt as though he had merged with the trees of the forest, reaching higher and higher until he touched the clouds. This was what had been missing from his life – warmth, intimacy, and passion.

For Angélique, too, much time had passed since she last made love. For weeks now, from the moment she first set eyes on Joseph in Ruisseau, she had wanted to caress him, nestle against his body, lose herself in his scent, and feel his embrace. The love she’d felt from that first day grew even stronger as she witnessed his respectful gentleness; she wouldn’t have waited any longer.

The shivers up and down her spine felt like a cloud of ocean spray. Her neck, her shoulders, and her breasts flushed with passion under his touch. Under his musician’s hands, each chord of her body became part of a symphony. Her pleasure intensified to the point where it seemed for a second she would forget how to breathe.

In the birch tree overhead, a swallow sang for them alone.

* * *

And so they continued that summer. A jealous Membertou, six years old, kept his distance. In Joseph’s presence, he showed nothing but indifference and spoke only Mi’kmaq. His attitude eventually enraged Joseph, especially since he had been trying so hard to win the boy over. Tough, undisciplined, always poking his nose where it shouldn’t be, Membertou did exactly as he pleased: a real little savage in Joseph’s eyes! Angélique tended to make excuses for him, she said his father had been a great warrior. The child spent his days wandering through the woods, eating in one tent or another, picking fights over nothing. There was no keeping track of all the mischief he got into. A week ago, as though inhabited by rage, he had hacked up a canoe. Then, to conceal the hut he built for himself in the forest, he stole several red fox hides from the storehouse. Saint-Jean, whose furs were more important to him than God, money, or women, had given his grandson a stern talking-to. Afterwards, Joseph insisted to Angélique that Membertou return the hides, but she hesitated, “With us, families are different,” she explained. “There’s no such thing as stealing. What belongs to one belongs to all. What children want is sacred. Children are given free rein and, when they grow up, they abide by the clan’s rules. Do you understand?”

“Yes, I do. You let them live a carefree childhood for longer, but don’t you think he’s gone too far, even by your customs?”

Angélique did find that her son was going too far, but pride stopped her from saying so. Exasperated and sensing he had no role to play in Membertou’s education, Joseph shouted, “You’re his slave, you’re not doing him a service.”

“I’m waiting for him to grow up and realize for himself that other people have rights as well. Be patient, it will come… Maybe you’re just jealous,” Angélique said.

“That’s quite possible,” Joseph retorted, “but I still would like to see him bring the furs back.”

Angélique was torn between her traditions and Joseph’s request, which seemed more like a demand. Eventually, she gave in. Membertou threw a terrible fit. He screamed, he threw himself on the ground, he broke his bow and arrows, he cried, he sulked, and he made threats. Nevertheless he did bring the red fox furs back to the storehouse.

Joseph breathed easier; now it felt like he could play a role in Membertou’s life. That evening, he lit a small fire in the centre of the big conical tent, spread pine branches on the ground to combat the humidity, and laid seal hides on top to make a bed. A bed for Membertou. Once the boy was asleep, Joseph took Angélique into his arms and forgot about having to become a father against his wishes. He was captivated by this woman who loved life, pleasure, beauty, and books. She was part-European after all, in love with the theatre, spending long hours as a child in the wild forests of Caraquet reading works by Molière, Corneille, and Racine brought in on French ships. She had been encouraged in her reading by her father who, as a youth, had shown an interest in the art of coin-making.

Membertou’s troubles had made Joseph think. He did not want the boy to become an obstacle in his relationship with Angélique. Which was why he decided to keep his distance as well, to feign indifference and act as though Membertou was not part of his life and wait for the boy to take the first step. The ploy was starting to work: one morning as they were fishing for trout, Membertou ventured a question about Quebec. “Are tents in Quebec bigger than Ruisseau’s?”

His question followed the sighting of large ships coming from Quebec, which were bigger than his people’s canoes…

* * *

The Mi’kmaq camp was still asleep, and the sun was just peeking above the point of Ile Caraquet, yet Saint-Jean was already boiling his morning tea in front of his home. He lived off on his own, in a log house with a roof covered in slate from the Anse à l’Etang quarry in the Gaspé. Until it went bankrupt, the quarry had supplied the city of Quebec with shingles. Saint-Jean, whose heart was ailing, added a special potion prepared by Angélique to his wintergreen tea: rye ergot to help his arteries contract. He had aged prematurely, his ten years spent on the king’s galleys having left their mark – wrinkled, cracked skin, hunched back, bald head, and long white beard. His soul was in a state of permanent revolt against injustice, governments, and institutions, which explained why he chose to live far away from so-called civilization. When hatred welled up at thoughts of the fate of his companions in misfortune, he channelled it into engraving onto moose antlers the facts of daily life on the galleys. He had a dream, too, that helped him go on: to create in America a fur empire to outfit the courts of Europe. “I want to show those good-for-nothings that they need those of us who aren’t as privileged as they are,” he proclaimed to all and sundry.

The animals of the forest held no secrets for Saint-Jean, nor did the different stages of hide preparation: cleaning, degreasing, brushing, lustring… His great weaknesses were those of the gourmand, namely the food and wine brought by the French ships that put in at Ruisseau. He had given himself over to these pleasures often since his wife’s death. But he’d been a gourmand since childhood, and his years of forced labour had only served to increase his appetite. He was obese, not a good thing given his health problems.

Joseph, too, had risen early. He pulled on a coarse linen shirt and baggy seaman’s pants cinched at the knee. He took his knife from where it hung at the entrance to the tent and headed in the direction of the great birch tree next to Saint-Jean’s house. Saint-Jean, whose survival had necessitated developing a biting sense of humour, called out, “Ready to make your getaway to Quebec?”

Pulled out of his revery, Joseph gave a start. “I want to write a letter to my mother, and mornings are my best time,” he answered.

His mother had taught him to read and write using old books from Normandy that told stories of Joan of Arc and William the Conqueror. The books also told his favourite tales – the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor – carrying the whiff of perfume from the Orient. Having leafed through the yellowed pages of the books hundreds of times, he knew all the tales by heart.

“Do you plan on telling her about Angélique?” Saint-Jean asked casually.

He viewed the relationship between his daughter and Joseph favourably, but he wanted to make sure Joseph would not be clearing out at the first snowfall. Joseph would rather not talk about it, but he decided to be open with the old man.

“That’s why I’m writing.”

“If you’re not sure, you should take some time to think about it.”

Joseph felt great affection for Saint-Jean; another man might not have trusted him so easily.

“No, my mind is made up. Sometimes I miss my family and the excitement of life in Quebec, but I feel at home here. The surroundings are beautiful, the people hospitable… and I love your daughter and I’ve begun to connect with Membertou.”

Satisfied, Saint-Jean lit his pipe and didn’t push the matter further. Joseph headed toward the huge birch tree and tore off large strips of bark for his letter to his mother concerning his future.