Читать книгу Trisha Brown - Susan Rosenberg - Страница 10

ОглавлениеMemory and Archive

A string: Homemade, Motor, Outside (1966)

2

The transition from improvisation (you’ll never see that again) to choreography (a dance form that can be precisely repeated) required great effort…. The ideas take a visual presence in the mind and one must find the method to decant that vision.— Trisha Brown1

Brown’s development of “a more systematized framework in which to behave” emerged in the three-part solo A string: Homemade, Motor, Outside (1966). Presented together with Brown’s Rulegame 5 (1964) on a March 29 and 30, 1966, concert (shared with a member of Judson Dance Theater, Deborah Hay), it marked the last of Brown’s three performances of her own work at Judson Church between 1963 and 1966—and her most ambitious choreography to date.

Together, A string’s three dances reveal Brown’s evolving sensibility with regard to her works’ site-determined nature, foreshadowed by Trillium. In juxtaposing dance to film in Homemade, to motion and technology in Motor, and to architecture in Outside, Brown introduced new, concrete models for framing choreography—“decanting it to vision”—all extending beyond Trillium’s elusive, metaphorical contrast of improvisation’s time-bound evanescence to choreography’s fixed, durable structure and context-based meanings.

Exceptional as the sole work from the early 1960s that Brown retained in her choreographic repertory, Homemade explores the issue of reprisal as a choreographic motif and choreographic-specific artistic problem. It presents a self-contained loop in which a live solo performance by Brown (wearing a simple black leotard and flesh-colored tights) is executed while she sports a film projector on her back—from which is screened, around the performance space, a 16 mm film shot by Robert Whitman showing Brown executing the same dance (with projector) that she performs live (see figure 2.2).

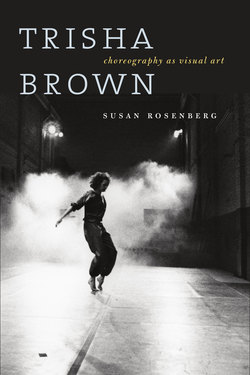

Figure 2.1 Robert Breer, program for Trisha Brown and Deborah Hay, Judson Church, March 29 and March 30, 1966. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Homemade has much in common with earlier “expanded-cinema” projects juxtaposing live performance with projected film. These include Elaine Summers’s “intermedia” Fantastic Gardens (1965) presented at Judson Church and two Robert Rauschenberg works that adopt this format (and in which Brown performed), Spring Training (1965) and Map Room II (1965). The latter appeared in the 1965 “Expanded Cinema” programs at Jonas Mekas’s Cinémathèque, where Robert Whitman’s Prune Flat (1966; figure 2.3) featured live performers whose bodies occasionally served as screens for projected images, and sometimes as hosts for images of the performers’ nude bodies.2

Compared with these examples, Brown’s decision to precisely coordinate the relationship between the dance and film in a single work illuminates choreographic-specific artistic concerns and her medium-specific thinking in Homemade, a multimedial artwork. In expanded cinema, live acts were joined with projected images to create boundary-defying confusion between the “real” and the “illusory,”3 and film was introduced to contexts other than the traditional cinema. Presented at Judson Church, Homemade’s film was (likewise) not contained by a screen or wall; as Brown turned in space, the film was thrown onto wall surfaces and ceilings, and directly into the audience’s eyes (as bright projected light), bringing attention to the architectural setting and encompassing the site in the performance.4

Rather than blurring the lines between art formats, using techniques of cinematic montage, incorporating found footage or combinations of live/projected images for the purpose of creating dreamlike cinematic experiences—as did other works of expanded cinema—Homemade emphasizes the distinctive capacities, functions, and properties of live dance and film as independent mediums. Their interrelationship and simultaneity serve Brown’s singular investigation of choreography, as grounded in the function of the dancer in the choreography’s two reproductions, one live and the other recorded on film.

Homemade produces a new understanding of the role of memory in choreography and of artistic problems that surround an individual choreography’s potential for revival, survival, and originality. It exposes implications of the originality and historical specificity of any individual choreography/performance, including the ways these pertain to a performer’s role in each work’s specific presentation. Extending concerns with memory, memorialization, and preservation that she had explored in Trillium (1962), Brown drew Homemade’s movement score from physicalized memories, performed (as she said) as a “live score” in which “each memory-unit is ‘lived,’ not performed.”5

Figure 2.2 Peter Moore, performance view of Trisha Brown’s Homemade, 1966. Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Figure 2.3 Robert Whitman, Prune Flat, 1966. © 1966 Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved

This combination of live and filmed dance contributes to the work’s deeply layered investigation of memory’s function in choreography, where it is an invisible but necessary component in the learning, repetition, and transmission of movement. Compared with other artists’ combination of live performance and film projection, Homemade stands apart for the unified, rigorously focused visual and conceptual nature of Brown’s artistic choices. All reveal memory’s function in choreography and dance, but also expose a much broader, discipline-specific problem for choreography: its potential to articulate its own definition of artistic originality.

Brown developed Homemade’s movements from a pedagogical model that she dated to Robert Dunn’s 1961–1962 class and teachings: there the use of “found” movement was the source of a new lexicon, common to many Judson Dance Theater members’ 1960s works. This method of “selecting” movement from everyday life and presenting it as dance relates to John Cage’s identification of music with “found sound” and, before him, to Marcel Duchamp’s nomination of “readymade objects” to the status of artworks: the recontextualization of banal “things” from the realm of the everyday to the art realm, provoking inquiry into art’s (or dance’s) definition.

Much as Trillium (1962) consolidated pedagogical principles and re-instantiated particular improvisational events, dating to Ann Halprin’s 1960 summer workshop—applying them to her thematic concern, memorialization—Homemade adopts an early 1960s lingua franca, “everyday movement,” structuring its use according to a systematic concept related to Brown’s work’s exploration of memory. As she explained, “I used memory as a score. I gave myself the instruction to enact and distill a series of meaningful memories, preferably those that impact on identity.”6 With this notion Brown excavated quotidian physical actions related to her childhood or to her current experience as a new mother—vivid movement forms instilled with a private reservoir of emotional affect.

Proposing that the body is an archival repository from which kinesthetic-cognitive material can be retrieved, Brown described Homemade’s movements as “vignettes of memory.”7 Her extraction and framing of pedestrian behaviors from the flow of everyday life and reminiscence so as to present them as dance are metonymically reiterated in the cinematic framing of the recorded version of the choreography.

As a solo dance composed of “microscopic movement taken from everyday activities, done so small they were unrecognizable,”8 the work’s juxtaposition of decontextualized, remembered behaviors tests the limits of gestures’ readability, suggesting a private sign language for which the audience lacks a manual. Interested in connotative gestures and images whose sources are disguised, Brown considered how movement might register on the edge of a viewer’s vision, eliciting her or his desire to impose order on actions that do not cohere in a narrative.

Many of the gestures’ sources are mysterious; others are readily recognizable—or can be correlated to documentations of Homemade’s components, which Brown wrote down when she reprised it in 1996. In its opening move Brown, with her legs subtly vibrating in place, turns a knob and pulls out a fishing line, an image also evocative of the spooling of film on an editing device. Some movements reference outdoor activities from her childhood growing up on the edge of the Olympic Peninsula’s forests and waterways. These include digging for clams, drawing in the sand, or throwing a football, but also activities such as blowing up a balloon or prancing as if one were wearing oversized shoes.

Brown gazes into an imaginary mirror, checks a wristwatch, nods in acquiescence to a teacher or “master”; she enacts domestic activities: holding, cradling, and kissing a young child or lifting an infant from his bassinet.9 Humor punctuates the dance’s relatively even-toned presentation: she emulates the prideful display of a “muscle man,” measures a large caught fish, and most dramatically, at the dance’s beginning, jumps into a pair of slippers placed on the floor. Deborah Jowitt described the actions as “the laundry list of a highly interesting housekeeper.”10

Robert Whitman’s color film zooms in on some of Homemade’s gestures and Brown’s facial expressions, enhancing the visibility of these small movements for the audience. The edits interrupt the smoothly flowing simultaneity of the live dance and its cinematic counterpart. These discrepancies call attention to a challenge faced by the performer: that of producing a rendition that keeps time with the projection, which is invisible, unfolding behind her. Through these dual simultaneous performances, Homemade makes visible the fact that each performative iteration of a choreography always slightly differs from every other, is subtly indeterminate in relation to the choreography’s enduring score. Ellipses in Whitman’s film highlight the impossibility of realizing perfect fidelity to an original choreography in any one example of its performances. Juxtaposing a live to a recorded dance heightens the experience of choreography’s visually precise forms, just as the film documents an individual (unique) performance and (imperfectly) records the choreography’s score.

In light of the dance’s miniaturized gestures and the film’s use of closeups, Carrie Lambert-Beatty interprets Homemade as punning on the idea of the performer’s “projection” of her onstage presence.11 Other interpretations are possible: the relationship of live dance and projected film foreshadows the rise of live feed projection; the video Portapak’s first artistic use dates to 1965. Brown’s effort to closely coordinate the dance’s two iterations evokes the possibility that the live act itself is being projected; the relation of body, apparatus, and projected images also recalls the inventor/photographer Julie Étienne-Marey’s experimental 1872 Odograph, in which a handheld stylus seismographically recorded foot movement patterns.12

The cinematic apparatus (including the electrical cord and sound of the projector’s motor) is clearly visible and audible, a physical object that Brown negotiates on the stage, reminiscent of visual artists’ (such as Bruce Nauman’s or Dan Flavin’s) refusal to hide the technology of cords and switches in their illuminated works.13 The film and title point to the idea of a home movie: many of movements were drawn from a time in Brown’s life after her son’s February 1965 birth: “I had a very young son, an infant, and this is before women’s liberation. It was a big question whether I could continue as a professional or not. The question came not from me, but from society. I worked at home a lot, taking care of this wonderful child and did a lot of my work in the studio that I had.”14

Homemade’s movements are executed in accordance with the (Cagean-derived) method Brown had applied in Trillium (1962): without transitions between them. As Brown said, introducing transitions was “likely to slur the beginning and the end of each discrete [movement] unit,”15 which she wished to be seen in a side-by-side serial fashion. By 1966, the placing of one thing after the other was a well-established compositional strategy in visual art adopted by painters and sculptors as a method for avoiding the appearance of subjectively inflected compositional decision making.

Especially important was Brown’s instruction to execute Homemade as a “live score” whose performance was not to be realized through the repetition of memorized movements, but instead by conceiving the body’s physical memories as deeply buried in it and made available through simultaneous access to the corporeal and the cognitive. With this notion Brown proposed that her performance involved a translation process, with her physical instrument mediating between thought/feeling, on the one hand, and kinesthetic articulation, on the other. Brown said, “The image, the memory, must occur in performance at precisely the same moment as the action derived from it. Without thinking, there are just physical feats.”16

Through the idea of memory as a mental/physical construct—available to reactivation—Brown sought to counteract the mindless repetition and practice of choreography as a deadening of the vitality of dance performance. Some years later, she reflected on the pernicious effect of memory on the process of keeping movement alive and enlivened during a choreography’s repetition in performance: she described how remembering and repeating a dance meant that she “lost it or ground it down or memorized it to death.”17

Homemade explores a counter-method for animating and reanimating movement and choreography: by envisaging it as an experience of mind-body integration, requiring in-the-moment retrieval of mental, physical, and emotional residue stored in and retrieved through the body. As in Trillium (1962), she emphasized the dancer’s active mind, not dance’s imitated physical shapes. The connectivity of mind and body in sourcing movement forms—her performance concept—underscores distinctions between Homemade’s vitalized iteration and the film, its pictorialized counterpart, absent a breathing three-dimensional body.

Brown’s use of film in Homemade recalls her recording of Simone Forti’s improvised vocalizations in Trillium (1962), where the memory and recreation of a lost example of improvisation had an artistic function related to the work’s meaning. Similarly, Homemade’s use of film serves her work’s artistic aims. It is not merely documentary, but contributes to visualizing choreography as a repeatable structure, seen both live and recorded. This idea intersects with competing theories about dance and its archivization.18 Some argue that the body is an archive and that dance is transmitted body-to-body (much as stories live on through oral history).19 This model emphasizes dance as an ephemeral art whose identity remains separate from its inscription through notation or in film or video. Other writers see dance as inseparable from its representation in documentation.20 Brown’s work refuses these distinctions while recognizing the time-bound historicity of each performance (as contrasted with fixed choreography). For the device to work, the same dancer must be seen simultaneously as alive on stage and recorded on film.

Brown’s evolving vision regarding the dynamic between choreography and improvisation is recorded in her statement “The transition from improvisation (you’ll never see that again) to choreography (a dance form that can be precisely repeated) required great effort…. The ideas take a visual presence in the mind and one must find the method to decant that vision.”21 If this concern and challenge would significantly inform her work with improvisation throughout her career, the combination of film and dance in Homemade extend and amplify Brown’s definition of choreography as a repeatable structure, imbuing this idea with new implications. Analog phonographs and film not only alter human perception of the “live.” Preserving the past through reproduction also impacts how we remember it.22 Homemade’s film clearly occupies a past (a performance preceding the live performance) that the audience witnesses;23 the temporal gap between the two events implies the work’s always having a history, almost as if, as an artwork, it escaped temporal limits to imaginatively occupy a “forever” as a self-contained artwork—so long as the rules for the combination of dance and film are respected.

It is only Brown’s instructions for Homemade that make it obvious she is visualizing a contrast between the body conceived as an archive (of memories/movements) and the functioning of film as a different method for providing dance with memory through inscriptive archivization. Homemade demonstrates that any choreographic idea is only and always reproduced, whether in a live performance or in a film record. This concept’s articulation in Homemade contests the notion that performance happens only in the moment.24

As an artwork, it presents audiences with the complicated experience of watching and comparing two different iterations of the choreography, making visible choreography’s consistency, coherence, and repeatability. The film, as a tangible artifact, announces Homemade’s choreography as that absence which is present, materialized in the body of the performer and on film; choreography is highlighted as a representation made manifest in two simultaneous, nearly identical performances.25 The relationship of the live to the film brings attention to the slim distinction between each of choreography’s iterations, showing choreography, as defined for Brown, by the idea, if not the actuality, of a permanent model.

The cinematic artifact announces a permanence to which choreography and dance aspire—but can only ever partially achieve, because they disappear and vanish.26 Brown’s showcasing of each dance movement’s ephemerality in performance, as compared to the cinematic recording, paradoxically reinforces the priority given to choreography’s relatively unchanging logic, her work’s center. Rather than being destined to immediately disappear, each individual, ephemeral performance of choreography encircles the idea of choreography’s potential to endure.

Homemade solidifies this concept of choreography’s permanence and performance’s originality in its apparatus. As a choreographic work defined by the marriage of performance and filmed reproduction, Homemade questions performance art theory’s separation of live performance from its documentation, instead applying this inquiry to question choreography’s definition, one of her works’ themes and concepts.

Her “double-exposed” dance compares to Robert Rauschenberg’s creation of two nearly identical but slightly different paintings, Factum I (1957) and Factum II (1957). (See figures 2.4 and 2.5.) As he said, “I painted two identical pictures, but only identical to the limits of the eye, the hand, the materials adjusting to the differences from one canvas to another.”27 As Branden W. Joseph notes, “At issue for Rauschenberg was not the exactness of reproduction but the difference within repetition.” He adds, “Though the differences between Rauschenberg’s two Factums thwart the viewer’s mnemonic capacities they do not simply disappear in the observation of one canvas alone. Rather, they continue to haunt each individual work, rendering it incomplete and defeating any claim to full self-presence. Thus neither canvas can any longer attain the solidity and self-identity that can privilege it as an original against which the other can be judged as a copy.”28

The same is true for Brown’s Homemade—albeit with an important difference, which concerns the property of artistic originality in its specific pertinence to choreography. As Rauschenberg does in Factum I and Factum II, Brown requires the audience to make choices regarding their focus on the dance or the film, implying a similar problematization of originality through these two mediums’ juxtaposition. However, if the duality of Rauschenberg’s two nearly identical Factums overturns conventional notions of originality in painting, Homemade insists on the idea of originality’s possibility for choreography, a concept manifested through the function of the singular (and original) dancer whose body/performance mediates between Homemade’s two reproductions—a precise and true understanding of the way any individual dance performance is a unique interpretation.

Figure 2.4 Robert Rauschenberg, Factum I, 1957. Oil, ink, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, newspaper, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas, 61½ × 35¾ in. (156.2 × 90.8 cm). The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, The Panza Collection. Art © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Figure 2.5 Robert Rauschenberg, Factum II, 1957. Oil, ink, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, newspaper, printed reproductions, and painted paper on canvas, 61⅜ × 35½ in. (155.9 × 90.2 cm). Purchase and an anonymous gift and Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest (both by exchange). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Art © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Homemade requires the seamless self-identity of the dancer in both components. Without the particular dancer who appears in the film, Homemade cannot function: the film was not conceived as independent of the artwork for which it was created. While exploring the issue of a dance’s longevity (through its recording), Homemade also invites reflection on choreography’s death and ephemerality. If a successful production or reprisal of Homemade depends on the participation and life of the performer, the dance pre-envisions its own expiration as contingent on the life or expiration of the dancer who embodies the choreography in both of its iterations.

Early in her career, in 1964, Brown expressed a powerful dedication to the notion of authorship and originality in the realm of live performance. Writing to Yvonne Rainer she reported that Ann Halprin had asked Brown and her husband “to do the undressing bit we did in Whitman’s FLOWER. I don’t get that attitude,” she wrote. “I told her we would if Whitman gave her permission and I guess that was the end of that.”29 In other words, she deferred to Whitman’s authorship, ownership, and rights to his performance as an original artwork and believed that her re-presentation of it, without his authorization, would be an act of theft and forgery. Homemade consolidates her ideas about a performance’s authorship, authenticity, and originality.

Marking the first of many instances when Brown explored the visual experience of “split perception,” or what she later described as “visual deflection,” Homemade’s format relates to instructions for performance announced in John Cage’s lecture “Where Are We Going? And What Are We Doing?”: “A performance must be given by a single lecturer. He may read ‘live’ any one of the lectures. The ‘live’ reading may be superimposed on the recorded readings. Or the whole may be recorded and delivered mechanically.”30

In Cage’s “45′ for a Speaker,” he questioned the division between listening and watching, envisioning the theatricalization of musical experience and conditions wherein the audience’s attention would be divided: “Music is one part of theater. ‘Focus’ is what aspects one’s noticing. There is all the various things going on at the same time. I have noticed that music is liveliest for me when listening for instance doesn’t distract me from seeing.”31

Brown re-opened this question of split focus, superimposed performances, as well as Homemade’s perpetuation (or potential loss) when she reprised it in 1996. In an especially poignant rendition of the work, presented on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, Brown reconstituted Homemade (1966) as a dance between her sixty-six-year-old self and her former self, aged thirty, whose image (in Whitman’s original film) accompanied the live performance (see figure 2.6).

Her continued fascination with the idea that a particular choreography owes its origin and provenance to the choreographer who originally made it and to the dancer who performs it was evident in Brown’s contribution to Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project’s Judson Revival program, “Past Forward” (2000–2001). For that occasion, she invited Baryshnikov to re-create the work and filmmaker Babette Mangolte to contribute its cinematic component, this time filmed in Super 8 mm in a studio at P.S. 122 in New York’s East Village.32

In a film by Charles Atlas screened as the prologue to the “Past Forward” performance program at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, June 7, 2001, Brown’s voiceover accompanies footage of Baryshnikov rehearsing Homemade. We hear Brown, unseen, instructing, “Physicalize a memory … You know there’s that purity of the first time you try something … It’s beautiful … It’s almost the same … but more from your experience.”33 The clip captures Brown’s use of the “live score” idea in welcoming Baryshnikov to introduce his memories to the work. Her approach to including Homemade on a program devoted to reviving artworks made in the 1960s speaks to Brown’s convictions regarding the impossibility of any truly authentic revival, offering, through Homemade’s a contemporary re-rendering, a demonstration of the inseparable dynamic between originality and repetition.

This new original combination of dance and film substituted for Brown’s performance, with Baryshnikov’s appearance bringing the work alive again, and at a particular moment (see figure 2.7). This attitude regarding her “Judson works” reflects Brown’s conviction that all but Homemade (a work exploring repeatability as an idea) should be assigned to her juvenilia as unique original dances. From that period she let go of her improvised solo (Trillium), her improvised duet with Steve Paxton (Lightfall, 1963; discussed in chapter 3), and Rulegame 5 (1964), which used dancers and nondancers and a simple game structure. Her remaking of Homemade in a 1996 version bypassed the notion of a “revival” or “reprisal” to insist on its integrity as contemporary artwork.

Figure 2.6 Trisha Brown performing Homemade, 1996. Photograph © Vincent Pereira, Trisha Brown Dance Company Archive, New York

Figure 2.7 Mikhail Baryshnikov performing Homemade, 2001. Photograph © 2015 Stephanie Berger

Brown’s insistence on preserving Homemade as the sole example of her work of the early 1960s is evident in her responses to various efforts to revisit, and canonize, the work of Judson Dance Theater. The first, in 1980–1982, organized by Wendy Perron, Tony Carruthers, and Dan Cameron—the Bennington College Judson Project—was a multi-year, multi-part enterprise (which included an exhibition, Judson Dance Theater: 1962–1966, at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, as well as extensive interviews with Judson participants). As part of the “Judson Project” residency/performance element, held at Bennington College on April 11, 1980, Brown presented Homemade but ignored the project’s historical premises, instead performing dances dating from 1975 and after, including (in this order) Accumulation (1971) with Talking (1973) plus Water Motor (1978) (1979), Locus (1975), Solo Olos (1977), “Message to Steve” (a work-in-progress that would become part of Opal Loop, 1980), as well her most recent work, “a fragment of Glacial Decoy (1979).”34

She declined to participate in any of the Bennington project’s New York performances at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, citing her focus on her current choreography.35 For Baryshnikov’s 2000–2001 “Past Forward” project, she remade Homemade for him to perform and also insisted on including a recent work in the program, emphasizing the priority of her present artistic concerns over nostalgic reminiscence.

Brown refused to participate in Danspace’s 2012 Judson Revival project, again insisting on her belief in her works’ historicity—an issue to which she remained closely attuned.36 In this case, Brown’s nonparticipation was also related to the fact that Homemade had just recently been performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. As to the status of her improvisational duet with Steve Paxton (Lightfall, 1963)—performed twice in the 1960s—Brown never reprised it, although in 1994 she reunited with Paxton for a new performed duet improvisation, Long and Dream, seen first at the Volkstheatre, Vienna (on August 12, 1994), and again at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (on October 2, 1996), as part of the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s thirty-fifth anniversary celebration.

For the 2012 Trisha Brown Dance Company program at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Homemade was executed by Vicky Shick, a choreographer and former Trisha Brown Dance Company member. It included a new film (actually a digital videotape) by Babette Mangolte. Shick (working with Carolyn Lucas, Brown’s choreographic assistant since 1994) not only studied Whitman’s film but revisited Brown’s notes on the dance’s original memory images. Her exquisite performance struck a sensitive and precise balancing of the theatrical, the actual/everyday, and the dramatization of nonchalant inner focus with a neutrality startling in its fidelity to the tonal qualities of Brown’s performance; this was exceptional in the way Shick interpreted the difference between moments of cartoon-like pantomimic exaggeration and humor (blowing up a balloon, slapping the thigh, doing a little tap dance) and others meant to be seen as private, mysterious, deeply concentrated or playfully self-regarding (looking into a mirror, setting up the slippers to jump into, and later on gamboling about in shoes that are more grown-up than their wearer). In her recording of Shick’s performance Mangolte replaced film technology (which she had used in working with Baryshnikov) with HD video. Her footage of Shick’s performance was screened from a video projector hidden within the original film apparatus—a choice common to curatorial efforts to retain and preserve historical examples of 1960s film/video by altering obsolescent technologies. The effect registered the slightly different ratio characteristic of the shift from an analog to a digital format.

Brown’s approach to these successive performances of Homemade reinforces its significance as a meditation on various memory-specific and historical dimensions of movement, choreography and their transmission as new originals in each iteration. The conceptual dimension of her outlook is highlighted when compared with choreographer Benjamin Millepied’s work, Years Later (2006), created for Mikhail Baryshnikov. Like Homemade it incorporates a film (by Asa Mader), which is projected on a flat screen behind Baryshnikov’s present-day performance of new choreography. Showing the young Baryshnikov rehearsing in a Moscow ballet studio, the film offers a contrast between his precocious agility as a dancer and the more limited repertoire of movement characteristic of his Years Later live performance.

A celebrity portrait of a legendary dancer, Millepied’s work uses film to reflect on human and technical dimensions of loss in dance, as well as on themes of exile and aging. Homemade’s film component provokes contemplation of the nature of originality particular to a dancer at a particular moment in time; and in it, film is a mobile element that, while fragmentary in its representation of the dance, also introduces the site and the audience into the event of the performance (whereas in Years Later, film remains a static projection appearing as a backdrop for the dancing).37

A specific site influenced A string’s second part, Motor (1965; figure 2.9). Premiered at “Unmarked Interchange: A Concert for Ann Arbor,” it joined other works presented by an offshoot of Judson Dance Theater that orbited around Robert Rauschenberg from 1965 to 1966. The occasion was the annual ONCE AGAIN Festival—the last of a series of ONCE festivals, which started in 1961, to feature performances by the Ann Arbor–based experimental and multimedial performative ONCE group founded by Robert Ashley (together with George Cacioppo, Gordon Mumma, Roger Reynolds, and Donald Scavarda).38

Presented to an audience of about four hundred people on the top floor of the Maynard Street parking garage, on the University of Michigan campus, Motor involved two props: a Volkswagen car and a skateboard. More specifically the work was (as Brown later described it) a “duet with a skateboard as timing device, and partner, performed in a parking lot, lit by a Volkswagen, driver unrehearsed.”39 The earliest instance of Brown’s taking inspiration from a specific performance site/context,40 Motor directly relates to Robert Rauschenberg’s first dance, Pelican (1963). Titled by Trisha Brown,41 it is the most famous, remembered element of “America on Wheels” (1963), an event held at the National Skating Rink in Washington, DC, to complement the exhibition The Popular Image at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art and a “Pop Festival”—both held in the gallery, which included concerts by John Cage (1912–1992) and David Tudor (1926–1996), Claes Oldenburg’s happening Stars, and a lecture by the critic and art historian Robert Rosenblum (1927–2006).

Brainchild of the curator Alice Denney (b. 1922), assistant director of the Washington Gallery of Modern Art (the sole contemporary art space in the nation’s capital at the time), the program brought the Judson group’s work to a wider swath of the visual art world than ever before; Judson Dance Theater was singled out the as festival’s most important feature. The Pasadena Museum assistant director Walter Hopps said, “Wow! Let’s fly the whole thing to the West Coast!”42 The Pop Festival’s exhibition proved controversial in bringing the work of artists representing a new sensibility—Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Jasper Johns, Tom Wesselmann, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Watts, John Wesley, and George Brecht—to the city, home of the Washington School of Color Field painters.

Figure 2.8 Peter Moore, performance view of Robert Rauschenberg’s Pelican, 1963 (1965 performance by Robert Rauschenberg, Carolyn Brown, and Alex Hay). Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Robert Dunn organized the dance program (considered to be Judson Concert #5) as a series of simultaneous performances arrayed around the National Skating Rink—as is recorded on the “America on Wheels” printed, diagrammatic program. Brown performed Trillium (1962) at the rink’s center, dramatically lit by an overhead spotlight; in addition, she presented her second work, a duet with Steve Paxton, Lightfall (1963)—recently premiered at Judson Church Concert #4 on January 30, 1963, Brown’s first presentation of her work in the church.

These Washington performances by Judson members were overshadowed by Rauschenberg’s Pelican, today known through iconic photographs, including one showing Rauschenberg in roller skates, sporting a cumbersome parachute on his back, with Per Olof Ultvedt supporting the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s star dancer, Carolyn Brown, outfitted in a casual gray sweat suit and performing en pointe.

As Steve Paxton recalled, Pelican included other forms of motion: Rauschenberg and Ultvedt “enter[ed] the rink, dressed in gray sweat suits and balanced on their knees on axles attached to bicycle wheels … which they turned by hand, rolling into the space” in fits and starts.43 Discarding the wheels, they suited up in “backpacks to which were attached large pieces of fabric, like parachutes”44 and in roller skates; they engaged Carolyn Brown by circling and supporting her dancing, before exiting, again, by kneeling on their hand-driven bicycle axles. A poetic, visual, and kinesthetic presentation of different movement possibilities,45 Pelican was in Rauschenberg words inspired by conditions of the site: “I favor a physical encounter of materials and ideas on a very literal, almost simpleminded plane.”46

Asked if the roller skating was Pelican’s syntax or unifying image, Rauschenberg emphasized the concrete, pragmatic aspects of his artistic decision making, telling Richard Kostelanetz, “No, it was just a form of locomotion. There were other wheels in the dance too. It was just that once I established the fact that I was going to call the dance a piece and didn’t want it to be a skating act … then somehow the other ingredients had to adjust to that; so that Carolyn Brown … was dancing on points, which is just as arbitrary a way of moving.”47

Motor, created for a parking garage, employed a car and, like Pelican, contrasts different methods of motion and locomotion. Revealing a penchant for reductive simplification similar to her choice of Trillium’s task movements, Motor charts movement’s trajectory from the human body to the earliest, locomotive apparatus—the wheel (of the skateboard)—to the industrial and mechanized motion represented by the car. The car’s utilitarian, nonillusionistic, nontheatrical light source—intrinsic to the object (car) and the performance—made for a context within the context of the garage. As in Pelican, where bicycle wheels, roller skates, and pointe shoes altered (and impaired) movement, the skateboard—with its formulaic opportunities for movement—provided resistance in Brown’s improvisation, as did the car’s unforeseeable, “unchoreographed” behavior and illumination.

Figure 2.9 Peter Moore, performance view of Trisha Brown’s Motor, 1965. Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Motor participates in a potent 1960s iconography, that of the automobile, the basis for George Brecht’s composition Motor Vehicle Sundown (Event) to John Cage (1960) and a major element of Robert Whitman’s Two Holes of Water—3 (1966), presented at “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering” (1966).48 Brecht said that Rauschenberg’s comments on a public panel at New York University inspired his work, whose score was published in An Anthology.49 Brown’s activation of the wheels of the skateboard, car, and headlights in relation to (undocumented) time structures echoes Brecht’s work, created for “any number of vehicles arranged outdoors” in which “there are at least as many sets of instruction cards as vehicles.” His score includes a list of possibilities for activating cars’ mechanisms—including headlights, parking lights, footlights, directional signal, inside light, glove compartment light, spot lamp, special lights, horns, sirens, bells, motor, windshield wipers, radio, seats, and doors—according to precise time structures.

As part of A string (1966), presented in the contained indoor setting of Judson Church, Brown replaced the car with a motor scooter. Jill Johnston compared it to a happening, implicitly relating it to Rauschenberg’s dance. Johnston wrote of Motor: “The use of objects in the second section achieved a dramatic impact much closer to the metaphorical license of the painter-happenings than the phenomenological approach to objects of many dancer happenings. In a blacked out space Miss Brown used a child’s skateboard to scoot on, run with, fall over, etc., as she was followed closely by a man on a motor scooter.”50

The final component of A string—Outside (1966)—defines its concept and movement source in relation to the architectural site of its making. Its premise connects to Brown’s exploration of frames and contexts in Motor and Homemade—albeit in a far more literal fashion. Its realization followed from Brown’s adoption of a loft-studio’s walls as the basis for a movement score, a situation she re-created when she presented the work at Judson Church.

She explained the importance of Outside’s geometric framework, how movements’ invention followed from cues delivered by a loft-studio’s wall surfaces. As Sally Banes reported (while renaming Outside “Inside,” as Brown did for a 1978 text published by Anne Livet), Brown “read the hardware, fixtures, woodwork, and various objects stored around the edges as instructions for movement,” explaining “Outside organizational methods force new patterns of construction.”51 Brown said she faced her studio wall “at a distance of twelve feet and beginning at the extreme left … read the wall as a score. While moving across the room to the far right,” she gleaned information about “speed, shape, duration or quality of a move [from] visual information on the wall … the architectural collection of alcove, door, peeling paint and pipes,” correlating these incidents with physical actions.52 “After finishing the first wall,” she said, “I repositioned myself in the same way for the second wall and repeated the procedure, [then] for the third and fourth.”53

This use of “structured improvisation”—a phrase coined by Simone Forti, whom Brown considered a most important mentor—had begun after Brown’s arrival in New York in the winter of 1961. Steve Paxton recalled watching Trisha and Simone demonstrating ‘improvisation’ in weekly workshops in James Waring’s space on Eighth Street and Third Avenue.54 Together with Paxton—in an illicit artistic behavior—they commandeered an unauthorized space on Great Jones Street as a studio.55

Brown recalls, “Simone would point blindly into the space and then follow out the end of her finger. From whatever there was, she would derive a set of rules about time and space that were complete enough to proceed with an improvisation.”56 Forti’s and Brown’s method of sourcing improvised movement dates to their participation in Ann Halprin’s 1960 workshop. Don McDonagh reported in Artforum in 1972 that Ann Halprin “began to work toward a type of dance activity that would draw upon its environment…. It was improvisation in which the resistance of materials … dictated the activity that the dancers would devise”; this approach to dance was unique in its time.57

There was a contextual element to Halprin’s teachings: improvisation was practiced on an outdoor dance deck conceived by Halprin’s husband, Lawrence Halprin, an architect/landscape architect (and former student of Walter Gropius at Harvard University’s School of Design in the 1950s). Located in the shadow of northern California’s Mount Tamalpais, the deck allowed for improvising in real space and time. Its structure, Lawrence Halprin said, was “conceived as a plane on which dance could be performed.” “Since it is not rectangular,” he added, “it generates a different influence on dance than does a space based on right angles.”58 Ann Halprin emphasized, “Walls are replaced by trees. Confining ceilings are nonexistent and the sky is a long way up…. There is a basic envelope of deep silence—punctuated by soft wind noises … the air is in constant movement.”59

Discussing “the powerful influence of the spatial structure,” “the non-rectangular form of the deck forc[ing] a complete reorientation of the dancers,” Halprin emphasized a natural relationship between the body, space, and movement.60 The setting informed movements’ scoring: “The customary points of reference are gone and in place of a cubic space all confined by right angels with front, back, sides and top—a box within which to move—the space explodes and becomes mobile. Movement within a moving space, I have found is different than movement within a static cube.”61

Forti, a longtime Halprin student and former member of Halprin’s company, felt the grid of New York City to be tiresome and confining. She writes Handbook in Motion, “It seemed to me that in New York my grid requirements had been structured by certain elements of human potential, of human function, of life function. But in a sense it tended towards closed systems. It lacked certain channels of openness to systems we cannot comprehend.”62 Forti’s outlook is consistent with her interest in movement’s organic dimensions.

When Brown transposed Halprin’s improvisational model to New York, it was in reference to the static cube and grid that she originated her choreography and on which its presentation depended. Taking inspiration from incidental aspects on a wall surface, Brown’s movement was, she said, “concretely specific to me, [but] abstract to the audience.”63 A circumscribed physical structure solved the problem of the choreography’s start and finish; the objective geometric frame constrained subjective choice making in movements’ generation. Brown underscored the wall’s importance as an external impersonal touchstone: “I remember being surprised when my right foot would be activated by a valve sticking out of the wall. I would not have selected the distribution of movement across my body on my own.”64

The sole reviewer of Brown’s performance of Outside at Judson Church, Jill Johnston described Brown’s “silky kinetic ease and presence.”65 She wrote, “I’d like to call it electrifying if the term can be understood in some subtle sense of a charge emanating from someplace inside what the thing looks like, which is warm, direct, calm, unself-righteously confident.”66 As with Trillium (1962) she expressed appreciation for Brown’s talent as a dancer, calling her “one of an almost zero number who can make ‘dance’ movement unconventional by seeming to exert no effort in letting it come alive,”67 an achievement that Johnston singled out as a “power manifest in the third part of A string”—that is, Outside.68

When Brown presented Outside at Judson Church, she placed the audience’s seats around her dance in a configuration that reproduced the studio’s original framing context, applying a method for improvising outdoors and in nature (California) to New York, where her concern with movement’s structural framing was an element internal to the work. In Outside the relationship between the soloist (Brown) and her audience was intimate. She recalls “mov[ing] along the edge of the room, facing out, on the kneecaps of the audience, who were placed in a rectangular seating formation, duplicating the interior of my studio. I was marking the edge of the space, leaving the center of the room empty.”69

Brown has stated that she cultivated a performance affect different from that of her peers in Judson Dance Theater: “Up until that time,” she said, “dancers in dance companies were doing rigorous technical steps and one of the mannerisms was to glaze over the eyes and kick up a storm…. Many people used that device to hide from the audience; we all knew about it and talked about it.”70 Yvonne Rainer’s approach was to negate what she called “exhibition-like” performance qualities “counteracting the ‘problem’ of performance … by never permitting the performers to confront the audience. Either the gaze was averted or the head was engaged in a movement.”71 Brown instead adopted a neutral, placid, but lively nonchalance, saying, “I decided to confront my audience straight ahead. As I traveled right along the edge of their knees … I looked at each person. It wasn’t dramatic or confrontational, just the way you look when you’re riding on a bus and notice everything.”72

Anticipated by Trillium—in which she held the work up to critical scrutiny by presenting it in two different contexts (New York and New London)—Outside reinscribes, within the presentation context itself, architectural constraints that had informed the work’s inception. Her approach reflects a strategy common to mid-1960s visual art. In Sol LeWitt’s Wall/Floor Piece (Three Squares) (1966), three identical square structures (with their centers’ empty) are placed in a corner—one on the floor and the others side-by-side, on two perpendicular walls to map the room’s architecture—reiterating the gallery’s interior architecture, with the viewer inhabiting the same real-space, real-time dimensions of the artwork (see figure 2.10).

In Bruce Nauman’s Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (Square Dance) (1967–1968)—which postdates Outside—a square’s perimeter is marked on the floor. The artist, facing inward to its center, steps at the halfway point of each of the square’s sides, circulating around the perimeter to the sound of a metronome (see figure 2.11).

Describing this (and other movement-based works made for recording on film), he told Willoughby Sharp, “I thought of them as dance-problems without being a dancer.”73 Also relevant to Brown’s piece, is Mel Bochner’s Measurement: Room (1969; figure 2.12), which transforms a gallery into a surface for a drawn line that demarcates each surface’s dimensions while implicating the viewer in the contrast between “abstract systems of knowledge and real, embodied perception.”74

Figure 2.10 Sol LeWitt, Wall/Floor Piece (Three Squares), 1966. Private collection. © 2015 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The LeWitt Estate

Figure 2.11 Bruce Nauman, Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (Square Dance), 1967–1968. Still from 16 mm film, black and white, sound, 400 feet, approx. 10 min. © 2015 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix, New York

In 1978 Brown notated Outside’s simple diagrammatic score for publication in Anne Livet’s Contemporary Dance; she drew a rectangle with arrows pointing counterclockwise around its perimeter. Her decision to record the architectural, site-related dimension of her work—its geometric shape—with no information about Outside’s improvised movement—which is lost to time—retroactively recognizes the importance of structures, planes, surfaces, and physical sites for her later works. The image reveals Brown’s conviction that it is through tangible structures, and/or their inscription, that choreography lasts beyond the instance of any single example of a work’s evanescent movement or performance.

Outside looks forward to Brown’s next body of work, the “Equipment Dances,” in which she adopted architecture and sculptural constructions—found and made—to define her choreographic scores and task-based movements, further marrying her approach to John Cage’s ideas. Self-generating and self-contained, the objective logic of the “Equipment Dances” ensured the authenticity of each work’s performance. The severity of Brown’s structured situations—intrinsic to her visualization of choreography—also creates an effect of authenticity, since imitation is neutralized as an element of their performance. Paradoxically Brown’s increasingly reductive definition of choreography as structure and duration brought her work to an intimate conversation with visual art.

Figure 2.12 Mel Bochner, Measurement: Room, 1969. Tape and Letraset on wall, size determined by installation. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York. Installation view: Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich, 1969. © 2015 Mel Bochner. Photograph © Erik Mosel, Munich, Germany