Читать книгу Trisha Brown - Susan Rosenberg - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

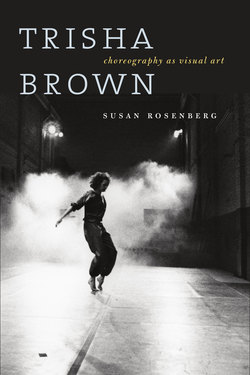

ОглавлениеIn a Crack between Dance and Art

“Equipment Dances” (1968–1971)

3

There were so few choices; the structure, the set up, made the choices. Now that comes out of my view on making and choreographing movement.— Trisha Brown1

Planes (1968) inaugurated a new body of works—all orchestrated in relation to architecture and sculpture, and all radically reorienting dancers’ relationship to gravity. In retrospect, it established Brown’s model of serial production, here as the basis for a group of choreographies produced in relation to the architecture of downtown SoHo, a relatively desolate part of New York that was home to a vanishing manufacturing industry, whose empty loft spaces were colonized by an influx of artists-inhabitants in the 1960s. The dances that followed from Planes—Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, Walking on the Wall, Rummage Sale and Floor of the Forest, and Leaning Duets—emerged at a culturally revolutionary moment beginning in 1968, when disruptions to the fabric of everyday life turned hierarchies of power and authority upside down and when the United States’ NASA space program showed gravity to be contingent, not natural, but a condition of life on Earth. As contemporary art and art criticism became impregnated by the writings of the French philosopher of phenomenology Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Brown’s works were named “Equipment Dances” in the first critical essay ever published on Brown’s work, written by Sally Sommer.2

Sommer’s title resonates with psychologist James R. Gibson’s writing in The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (1966). Focusing on the body’s phenomenological experience of space, he argues, “The equipment of feeling is automatically the same equipment as for doing.”3 His ideas about how the body “extract[s] information from the environment … to provide orientation to the ground as a relatively reliable surface of support”4 seemingly informed Sommer’s analysis of Brown’s works’ effects: the way her use of “equipment” positions dancers in extraordinary, antigravity situations to affect audience perception of everyday movement.5

In the “Equipment Dances,” pedestrian movement—a lexicon common to participants in Robert Dunn’s class—is stressed by architectural structures and by gravity’s inevitable motor. Rather than just question whether an everyday action could be considered dance, Brown made these actions subject to movement scores produced by material sites—walls or objects. In the process she challenged expectations about where dance is presented and seen, and brought visual scrutiny to the choreographed nature of quotidian movement forms.

Building facades compelled her imagination as a young mother wheeling her son’s stroller through SoHo: “I was excluded from traditional theaters … because of the economics of dance, so the streets became one of the few places I could do my works.”6 Defining choreography’s parameters in terms of objective structures, Brown externalized, visualized, and displaced the intentionality governing movements’ initiating impulses. The “Equipment Dances” cancel any concerns but for the structuring of choreography, eliminating the appearance that arbitrary choice making is her work’s source. Devoted to Cage’s emphasis on evacuating subjectivity from composition, this body of works uses literal structures to constrain performers’ subjective volition. A 1970 notebook entry confirms Brown’s preoccupations: “Movement has always interested me. The problem is what to move—where to move it and why move it.”7 “Construction pieces,” Brown said, “defined simple movement possibilities that eliminated the problem of choice of gesture.”8

Everyday movement is revealed as a series of minute physical choices and cognitive-kinesthetic negotiations necessary to execute actions that are assumed to be “natural.” Subjected to “equipment,” movement’s components become visible, much as Eadweard Muybridge’s stop-action photography brought scrutiny to animal and human locomotion.9

Brown’s siting of her work outside of any connection to dance or art institution was not an emulation of visual artists’ circumvention of the commercial art system’s values. Context was the basis for empirical queries into choreography’s component elements. It was also expedient: venues for young choreographers’ work were limited.10 Her concern with choreography’s elements opened dialogue with visual art, where gravity and site specificity were central to contemporary sculpture.

Figure 3.1 Peter Moore, performance view of Trisha Brown’s Lightfall, 1963 (Judson Church performance by Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton). Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Recalling her works’ fragility and her artistic isolation, Brown said, “No one could buy my work in the art world, and the dance world said it wasn’t dance—which it probably wasn’t. I was caught in a crack doing serious work in a field that wasn’t ready for it.”11 Between Planes (1968), her self-produced program “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” (1980), and her 1971 Whitney Museum program “Another Fearless Dance Concert,” that crack narrowed, facilitating her works’ entry into the visual art context.

In Planes Brown reimagined dance’s relationship to space and gravity, looking back to two 1963 works, Lightfall and Chanteuse Excentrique Américaine. The former, a duet created with Steve Paxton, was the first of Brown’s dances to be shown at Judson Church at Concert #4, January 30, 1963. Based on the instruction “to fall,” it was a game of task-based actions: one dancer crouches like a football player waiting for a play to begin; the other hops to sit on his or her back, but then is dumped to the ground when the supporting partner stands up, activating gravity’s entropic effect.12 Repeatedly rendered with the same expenditure of effort, Lightfall was accompanied by a soundtrack of Simone Forti’s whistling13 and was an obvious rejoinder to gravity-defying leaps and elevations in ballet and modern dance, as well as to falling’s codification in Doris Humphrey’s and Martha Graham’s techniques, and was therein a response to Yvonne Rainer’s critique of dance virtuosity in her 1966 “NO” manifesto. Lightfall also retranslates to choreography the legacy of Jackson Pollock’s use of gravity as a device in his drip paintings.

Rainer titled Lightfall, seeing it as “delicate in tone but still projecting an element of danger.”14 Robert Rauschenberg said it showed “how much risk they could take.”15 Jill Johnston wrote, “The dancers initiated a spontaneous series of interferences—ass-bumping and back-hopping—which were artless, playful excursions in quiet expectancy and unusual surprises,” continuing, “Brown has a genius for improvisation, for being ready when the moment calls, for being ‘there’ when the moment arrives,” describing this as “the result of an interior calm and confidence and of highly developed kinesthetic responses. She’s really relaxed and beautiful.”16

On June 10, 1963, Brown repurposed falling in Chanteuse Excentrique Américaine, transforming it into a harsh single act. She assumed ballet’s fourth position, leaned over, and as she remembered, “I held it as long as I could, and hit like a ton of bricks”17 while saying, “Oh no, Oh no.”18 She compared the fall to the effect of a “dead weight, like a tree cut down.”19 Titled by James Waring, it premiered at the “Pocket Follies,” at New York’s Pocket Theater (Third Avenue at Thirteenth Street), a program benefiting the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts (founded by John Cage, Jasper Johns, and Merce Cunningham).20 Chanteuse exemplifies what Liz Kotz characterized as “a new type of work [that] began to appear [around 1960 in New York] consist[ing] of short instruction-like texts proposing one or more actions. Frequently referred to under the rubric of ‘event scores’ or ‘word pieces,’ they represent one response to the work of John Cage.”21 Related to the musical concepts of La Monte Young and to “events” pioneered by the Fluxus artist George Brecht, Chanteuse reveals a “[delimitation] of the work to a single event or object,”22 anticipating the focal role of gravity in the “Equipment Dances.” While gravity’s use as movement’s generator in Lightfall reversed Trillium’s hallmark levitational moment, the “Equipment Dances” brought together interests in movement impacted by gravity with dancers who appear to be untouched by its effect.

Planes (see figure 3.2) premiered in a traveling festival of interdisciplinary, technology-driven collaborative artworks, “Intermedia ’68.” John Brockman, its organizer (a twenty-six-year-old Columbia Business School graduate),23 clearly borrowed concepts from the ambitious collaborative “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering,” (1966), the brainchild of the Bell Lab technician Billy Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg, which emerged from intensive dialogue between artists and engineers that resulted in sensational performances over nine nights at New York’s Lexington Avenue Armory.

Brockman’s commercially savvy program brought together underground 1960s artistic impulses—happenings, Fluxus, sound, and dance performance—in a project whose conception was based on artistic collaboration and that was created specifically to travel to different venues and attract wider audiences to avant-garde performance.24 He promoted “Intermedia ’68” with language drawn from descriptions of conceptual art—as a dematerialization of the object: “These people traffic in experience, not objects,” which “involves going to museums where objects hang on the wall and say ‘Look at me’ and the people look at the picture and see which artist did it, and then move on and it’s all finished.”25 “Who wants objects?” Brockman asked. “What’s interesting is process—seeing, feeling, sensation, the environment.”26

Many definitions of “intermedia” proliferated in New York beginning in 1966. Dick Higgin said it was “art that falls conceptually between established or traditional media.”27 Jud Yalkut’s “Critique: Understanding Intermedia” described overlapping “avenues of musical composition, an area expanded by composers … dancers … painters … and filmmakers” and recognized arts’ cross-pollination as a national phenomenon.28 For “Intermedia ’68” Brown collaborated with Yalkut, a filmmaker, close associate of Nam June Paik, founder of the USCO Collective, and pioneer of video art. He responded to Brown’s request for a film that “disguised gravity,”29 augmenting a choreography begun in 1967 by creating “technology that allowed [her] to support [her]self on a surface that was near-perfect vertical.”30

She altered a wall in her loft at 27 Howard Street, sinking “metal eyes into its surface [to] serv[e] as hand-and foot-holds”;31 this enabled “three dancers to appear to be free-falling as they traveled the area in slow end over end motion.”32 Her use of a surface plane was preceded by her experience of Halprin’s outdoor dance deck, “conceived,” Halprin said, “as a plane on which dance could be performed” and created in response to the site described by its architect, Lawrence Halprin, as “a level platform floating above the ground.”33

Figure 3.2 Trisha Brown, Planes, 1968. Photograph © 2015 Wayne A. Hollingworth, Trisha Brown Archive, New York

The deck’s natural siting inspired open-ended improvisation in real space and time. Oriented vertically, the surface of Brown’s plane produced “a certain kind of movement that had nothing to do with dance gesture’s organization of people and space as I had thought about it before. It was to see the wall deliver the dancers to the movement: as a machine.”34 Planes restricted movements’ travel to limbs’ extension across the vertical pegboard’s “steps.” Dancers grasped hand-and footholds, moving up, down, and sideways in 90-, 180-, or 360-degree rotations.

After moving to a new loft at 80 Wooster Street, one of George Maciunas’s first Fluxhouse cooperatives,35 she heightened the illusion of weightlessness: “We built the grid … It had holes cut out of a very large surface … evenly spaced … [so that] three dancers appear to be free-falling … travel-[ing] the area in slow, end over end motion.”36 The effect of the dancers’ suspension in space was enhanced, its mechanism less obvious. The new surface also “alleviated the pain of standing on metal hook-holds,” which Brown said were “so horrible for my feet,”37 a detail signaling her commitment to noninjurious movement, one of her works’ constant leitmotifs.38 Brown recognized that she was “making a bold step … doing something very large and out of the ordinary. So much of women’s work was in her lap. This was a monumental structure—the scale, the steepness and the difficulty of it.”39

Planes did not reveal physical struggle; the New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff saw in it a “startling and beautiful effect of weightlessness.”40 When Brown visited the Walker Art Center to see Planes’ first reprisal since 1968 as part of the 2008 exhibition Trisha Brown: So the Audience Does Not Know Whether I Have Stopped Dancing, curated by Peter Eleey, she recognized, with fascination, the artifice of her representation of “truths” about the body and gravity: “When you walk on a wall,” she said, “if you actually were to just relax, everything would hang down. You don’t have all the signals you get when you are upright, about where your arm or head should be, so you have to invent that.”41 In the years since Planes’ premiere, popular climbing walls in sporting goods stores have replicated its format. Brown’s attunement to the effects of changing contexts on her work inspired stylization of what was initially unadorned movement: in 2008 she introduced a new element, with dancers climbing over one another to traverse the wall.42

Yalkut said Brown’s vision of locating movement on a physical object in Planes—a wall hosting her dance and his film’s projection, set on a darkened stage—attracted him as an innovative contribution to expanded cinema.43 This brought a formal rigor to the combination of live performance with projected film. The wall circumscribed their multimedia work to reassert art’s boundaries, even as Planes’ cinematic projection encompasses dance in layered, collaged images, a shifting scenographic surround in which performers, costumed in two-sided jumpsuits—white on one side and black on the other—appear/disappear as their facings shift.

This coordination of theater and object has few reference points. The June 2, 1967, “Manifestation 3,” staged in the theater of the Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris, by Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni (known collectively as BMPT), joined visual art and theater without a bodily component. On the stage each artist presented an abstract painting. Expecting a performance, the audience instead saw two-dimensional art, a collision devised to query an institutional context’s impact on abstract art’s meaning/reception.44

Figure 3.3 Daniel Buren, BMPT Manifestation, 1967. © 2015 DB-ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery, London

Cued by Brown’s concern with space and perception Yalkut conceived the film in terms of “several different levels for the eye or surface of the eye, elevating it into outer space in series of levels, or planes.”45 His visionary imagery extended earlier multimedia, “psychedelic” collaborations with Marshall McLuhan and Timothy Leary,46 incorporating macro-and micro-perspectives; natural, scientific, human, and technological subject matter; and footage both found and made—techniques and subject matter that consciously looked back to Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s “New Vision” of the 1920s.

Opening with fast zooms into an elevator airshaft at 80 Wooster Street, the film layers black-and-white over color footage, and negative over positive. It contains aerial shots of Manhattan’s skyline, taken from a helicopter flying over the Hudson River, juxtaposed with street-level urban images filmed from a moving car or from atop the Empire State Building.47 Found footage—Earth shot from space, a solar eclipse, rocket blasts, floating dirigibles, aerial images of crowd scenes and Muslims prostrated in prayer—coexists with scientific images of microbes. Rhythmic cutting produces a narrative of rebirth, reentry, and expanding consciousness. The film ends with color shots of an infant suspended over a cityscape, images of the aurora borealis, and parachutists descending through space to Earth. Interested in Eastern mysticism,48 he featured “corollaries between psychic space and the physical escape of consciousness beyond the earth’s biosphere … culminating in the brief and rapid deceleration of re-entry.”49

Yalkut introduced color images of Simone Forti, improvising inside a plastic bubble “star form” sculpture by the artist Les Levine, suspended on saw horses at 80 Wooster Street.50 With a fish-eye lens on his 16 mm Bolex camera, he recorded her motions inside the acrylic structure, producing novel, distorting perspectives on her body, which appear intermittently, superimposed on the black-and-white “A” reel (discussed earlier). The structure was a damaged version of his vacuum form Plexi sculptures, made at 80 Wooster Street and then for Yalkut’s film mocked up on sawhorses on the building’s roof where Yalkut filmed Forti.51 It dates to Levine’s 1967 exhibition, Star Garden (A Place), shown on an outdoor terrace at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.52 An April 1, 1967, press release described it as “an architectural device … made of acrylic plastic sheets … heated and then shaped by jets of air into rounded forms” with transparent seven-foot-high bubbles: overall dimension of 40 square feet. An early example of “interactive” art, “the work,” MoMA’s release said, “is not complete until an individual walks through it.”53 Forti supplied vocalizations to fulfill Yalkut’s idea of joining human chanting with a mechanical hum (of a vacuum cleaner).54

Simone Forti, Trisha Brown, and Michelle Friedman performed Planes in the “Intermedia ’68” programs, which traveled to the State University of New York at Stony Brook, New Paltz, Albany, and Buffalo; Nassau Community College; Rockland Community College; Nazareth and St. John Fisher Colleges in Rochester; and Buffalo’s Albright Knox Gallery. Performances concluded at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the first of many programs by Brown there beginning in the late 1970s, with Planes praised as a “gem,” and for showing “media [that] were still mixed but [with an] emphasis … on dance.”55

Figure 3.4 Robert Smithson, Asphalt Run-Down, outside Rome, October 1969. Photographer: Robert Smithson. Photo and Art © Holt Smithson Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Together with two of Brown’s performed improvisations, Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders (1967) and Yellowbelly (1968), Planes was included in the 1969 Festival of Music and Dance organized by Fabio Sargentini at his L’Attico Gallery in Rome,56 for which the Italian-born dancer/choreographer, Simone Forti was the conduit; she facilitated Sargentini’s New York visit to identify participants in his June 1969 program: Terry Riley, La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Deborah Hay, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and Simone Forti. Held in the parking garage that Sargentini acquired to showcase contemporary art, the performance was bracketed by Jannis Kounellis’s exhibition Untitled (12 Horses) (1969; including live horses) and by Robert Smithson’s Asphalt Run-Down (1969).57 Sharing Brown’s concern with gravity and entropy, Smithson’s work involved a dump truck unloading a mass of asphalt down a deserted hill outside of Rome, recorded in a photograph.

In 1968 Brown undertook a performance for the camera, which is preserved in slides, as well as in a newly conserved color film: it shows Trisha with cropped hair in a pink tutu and bent over two parallel, unstable ropes, moving on all fours with her ass in the air. The work, with its send-up title—Ballet—had its follow-up in an unrealized film project, also with a witty title: Autobiography (1970), which exists solely in still photographs (see figure 3.5). Together these two works anticipate aspects of Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), the most monumental work that Brown would present on her 1970 self-curated, self-produced “concert,” “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street.”

Ballet’s use of rope equipment anticipates this material’s vertical repurposing as part of an efficient new choreographic production system, while Autobiography previews its foundation in a pedestrian action surprisingly reoriented in relation to a quotidian situation. Part Fluxus event, part choreography, Autobiography involved Brown’s “endeavor[ing] to collapse and organize my mornings on the hood of a car. I had a camper stove, and I lit it. I sat there on the hood drinking coffee, then performed yoga while the car drove around Naponack, where, at the time, I owned ten acres of land.”58 While evocative of works such as Music by Alison (1964) in which—sitting on a chair on Mercer Street—Fluxus artist Alison Knowles shook out her clothing, Autobiography is a dance: its title puns on the autobiographical actions unfolding on an automobile’s roof with the car serving as the dance’s vehicle of travel.

Brown used Carol Goodden’s test still for Autobiography to promote her April 18, 1970, “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” (1970): the picture shows her outfitted in patterned culottes and a striped T-shirt, executing a yoga shoulder stand on a car roof. The image tantalizingly predicts the astonishingly inverted everyday behavior seen in Man Walking and in other works’ siting in a relation to the totality of the environment surrounding Brown’s residence (see figure 3.6).

Dances were performed in an interior courtyard, on the second floor (Jonas Mekas’s Cinémathèque), and on the street. Brown embraced a location that a 1974 New York Times headline deemed “Gray, Grimy Wooster Street”59 and an aesthetic of urban detritus inspired by Robert Rauschenberg’s work.60 She said, “I wanted to work with the wall … It was dark, dirty and there were exteriors of buildings that could become a place for a sort of performance. I chose this exterior wall and then thought—why not use mountain climbing equipment? I checked this out with Richard Nonas … and a few other guys that knew about dangerous acts in the world.”61

Figure 3.5 Trisha Brown, Autobiography, 1970. Photograph by Carol Goodden

Conceived as a simple walk down the surface of the interior courtyard of her seven-floor loft building, Brown realized Man Walking with basic mountaineering equipment purchased at Tent and Trail’s Chamber Street store. Rigging the body, like Cage’s preparation of a piano, she situated two belayers, the artist and anthropologist/artist Richard Nonas and the artist Jared Bark, on 80 Wooster Street’s roof. Their manipulation of a simple rope-and-pulley system enabled the walker, her husband at the time, Joseph Schlichter, to release his weight into their hands and, as the film documentation reveals, perform a reasonably accurate reproduction of the act of walking. With back held straight, perpendicular to the building and parallel to the ground, he promenades, seemingly effortlessly, in an altered orientation to gravity’s inexorable logic (see figure 3.7).62

Man Walking redescribes the compositional logic of Cage’s indeterminacy lecture, “Composition as Process: Indeterminacy” (1958), published in Silence (1961). As described by Cage, with an invitation from the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik at Darmstadt, he “decided to make a lecture within the time length of his Music of Changes (each line of the text whether speech or silence requiring one second for its performance), so whenever [he] would stop speaking, the corresponding part of the Music of Changes itself would be played.”63 In a recorded iteration, “Indeterminacy, New Aspect of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music, Ninety Stories by John Cage with Music,” originally issued in 1959 as Folkways FT 3704, Cage presented ninety stories spoken aloud but so that each would take only one minute, a choreographing of time that he had earlier explored in “4′33″”. In that work, the activity of opening and closing the cover of the piano’s keyboard according to Cage’s deliberate structures, based on time, served to frame silence and thereby redefine ambient sound/noise as music.64 Man Walking equates time with the walker’s travel and path through space, between two fixed points of architecture (rather than in relation to parameters provided by a stopwatch’s increments).

Figure 3.6 Poster for “Dances in and Around 80 Wooster Street,” 1970. Photograph by Carol Goodden

Figure 3.7 Trisha Brown, Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, 1970. Photograph by Carol Goodden

Brown alluded to Cage’s ideas as her source: “All those soupy questions that arise in the process of selecting abstract movement according to the modern dance tradition—what, when, where and how—are solved in collaboration between choreographer and place. If you eliminate all those eccentric possibilities that the choreographic imagination can conjure and just have a person walk down an aisle, then you see the movement as an activity.”65 “This space of time is organized,” Cage wrote in “Lecture on Nothing.”66 Brown’s Man Walking replies, the space of a walk organizes time and visualizes space.

“Man Walking,” Brown said, “came out of a realization that modern dance has a method of choreography … that dance has a beginning, a middle and end. I thought where do I begin? You start at the top of the building and you tell them to walk down … And when they reach the ground it is the end. It had a structure to it, albeit a very spectacular dance,”67 a description that set her work against Yvonne Rainer’s emphasis on spectacle’s negation in her “NO” manifesto.68 Using “equipment” meant that there “were so few choices: the structure, the set up, made the choices.”69 Man Walking visualizes choreography-as-structure in relation to a site.

Describing her work as a “dance machine,” Brown evoked Sol LeWitt’s 1967 definition of conceptual art: “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes art.”70 As she said, “Man Walking was like doing Planes but purifying the image. It had no rationale. It was completely art.”71 Walking and running were common movement choices in 1960s dance: for example, in Yvonne Rainer’s We Shall Run (1963), where seven dancers and nondancers ran in patterns for twelve minutes to Berlioz’s Requiem (1837), and in Steve Paxton’s Satisfyin’ Lover (1967), where dancers and nondancers traverse space, stopping, sitting, and moving on, displaying a cornucopia of styles, comportments, and postures of walking manifested in different bodies. Paxton said pedestrian movement was used “to eliminate the look of learned movement.”72 To Judson participants’ inquiry “Can walking be dance?” Brown proposed a more fundamental question: “What is walking?”

Framed by architecture, and thereby both attached to and separate from everyday life, each incremental movement choice enacted under new empirical conditions made for a fictional re-creation of mundane behavior. The performance depends on the dancer’s physical memory and the organization of (or failure to organize) walking’s elements: legs, arms, back, hips, and head are adjusted in relation to a known activity, encompassed in language, in an effortful reconstruction whose greatest challenge is for the feet to maintain the effect of traction against the wall, while floating in space. Rather than showcasing pedestrian behavior to dispense with choreography, Man Walking reveals the choreographed aspect of everyday life’s forms.

When reprised at the Whitney Museum of American Art in September 2010, each performance started with the walker cantilevering forward in space with the soles of the feet barely touching the point where the building’s face joined the roof. One performer, the choreographer and first male dancer in the Trisha Brown Dance Company, Stephen Petronio, described “reaching [his] head into space and lengthening [his] body, to create tension against the building, while trying to hold onto space at the molecular level, even as the body [was] telling [him], ‘This should not be happening—don’t do this.’”73 The choreographer Elizabeth Streb, the first woman to perform the walk, recounted of her Whitney performance, “I felt like an idiot savant: like ‘I don’t remember how to walk.’”74

Edgar Degas’s preparatory sketch for the painting Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (1879)—on view at New York’s Morgan Library during the 2010 performance of Man Walking—is an antecedent of Brown’s dance. A woman is suspended, like a caught fish, from a high wire gripped in her mouth, and her body made strange by its role in a circus act. It details the apparatus of the performer’s suspension, a wooden plaque hollowed to hold her bite, attached to a simple hook—the mechanism of her upward lift to the tent’s heights.

Man Walking—particularly the 2010 version—likewise revealed the apparatus that made movement possible: this was because a new, highly visible metal rigging system was provided by a company that serves primarily the entertainment industry. Their technology was not optimal for the performances, but it would have been impossible to know that. However, when BANDALOOP’s Amelia Rudolph performed the work at UCLA in 2013, a less visible and simpler apparatus was used, and this made for a seemingly more natural performance.75

One could see the walker being held/lifted while trying to exert her or his weight/force to descend. The most natural of human acts is shown to be a function of gravity. The body becomes a material altered by structure, and choreography appears to be self-contained, self-generating, and object-like. Realized two years after Neil Armstrong’s historic, televised walk across the moon’s surface on July 11, 1969, Brown’s work resonated with popular interest in antigravity situations, which showed bodily experiences of weight, spatial coordination, and movement to be contingent, unnatural. A 1976 letter from the editor of Astronautics and Aeronautics sent news of her works’ resemblance to space-exploration research; Brown was invited to visit NASA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, to observe simulations of zero-gravity conditions in a scientific laboratory context.76

Man Walking condenses a vast legacy of postwar art, not only redefining dance, but also asserting choreography’s place in visual art tradition. In its transparent analysis of choreography’s elemental components, the work opens to cross-comparisons with visual artists’ works. Brown’s shift of walking from horizontality to verticality echoes Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955): a readymade object transformed by a 90-degree shift (plus the addition of paint) into an art object. Literally presented “off the wall,” Man Walking bears connection to Rauschenberg’s combines such as Canyon (1959), where an object suspended from the canvas’s frame enters real space, and Elgin Tie (1964), presented at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm (see figure 3.8).

Rauschenberg’s descent from ceiling to floor anticipated Brown’s vertical walk, just as it built on Simone Forti’s Slant Board (1961; figure 3.9), in which a wooden platform mounted at a 45-degree angle against a wall is attached with ropes that provide a movement score, inciting performers’ actual energy expenditure to perform the repeated tasks of climbing and descending this surface plane, negotiating gravity. Whereas the duration and number of repetitions in Forti’s dance are a matter of choice, Brown adopted the framing device of architecture to establish the parameters for her choreographic act.

Brown’s work resonates with La Monte Young’s Composition 1960 #1 to Bob Morris: Draw a Straight Line and Follow It (1960) and with Richard Long’s performative photograph, A Line Made by Walking (1967; figure 3.10).77 Her rigging of the body and intervention into urban space anticipate Gordon Matta-Clark’s site-specific, sculptural interventions into architecture and his 1973 Vassar College Tree Dance—and also coincide with Richard Serra’s rigging of his large-scale sculptural works.78

Carol Goodden, Matta-Clark’s companion, performed in Brown’s Leaning Duets [I] (1970) in the “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” program, presented on the street by five pairs of dancers: one version without “equipment” and the other using “rope devices with handles … to achieve a greater angle.”79 (See figure 3.11.) An elemental statement about gravity’s role in movement’s production, Leaning Duets pairs two dancers side to side, with feet planted adjacent to one another. Using their bodies as ballast, they cantilever away from one another and from gravity’s center. This precarious balance gives way, propelling their bodies’ forward momentum to repeat the task. Physical negotiation was accompanied by verbal communication: “Give me some weight” or “Give me a lot” or “Take a little.”80

Figure 3.8 Robert Rauschenberg, Elgin Tie, 1964. Image © Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Photograph by Stig T. Karlsson. Art © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York

Figure 3.9 Simone Forti, Slant Board, 1961. Photograph 1982, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Richard Serra’s One Ton Prop (House of Cards) (1969; figure 3.12) mobilizes gravity through the contingent, choreographed act of setting up four self-supporting lead slabs, unfastened and leaning against one another, to create a precariously balanced cube.81 Each lead square’s great weight implies falling’s potential danger, while exemplifying Serra’s idea of “choreography in relation to material.”82 Serra acknowledged dance’s influence as prompting him to consider the idea of “the body passing through space, and [its] movement not being predicated totally on image or sight or optical awareness, but on physical awareness in relation to space, place, time, movement.”83 Brown had written the dance critic Edward Denby hoping he would attend her performance84 whose gender-crossing dangerous act challenged a 1970s situation described by painter Susan Rothenberg: “The women were all dancers; the men were sculptors”85—a statement that captures period-specific thinking but not the fact that there were men who danced and women who sculpted. Brown later said that Yvonne Rainer, who missed the performance but had heard about it, remarked to Trisha, “That sounds tough.”86

Figure 3.10 Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967. Photograph and pencil on board, 375 × 324 mm. Tate Gallery, London, purchased 1976. © 2015 Richard Long. All Rights Reserved, DACS, London / ARS, NY. Photo: Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Figure 3.11 Peter Moore, performance view of Trisha Brown’s Leaning Duets, 1970. Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Presented in the second-floor space of Jonas Mekas’s Cinémathèque, Brown’s Floor of the Forest (1970; figures 3.13 and 3.14) structured the performance, as well as the audience’s relationship to it, through a three-dimensional metal structure, 12 by 14 feet, suspended from the ceiling at viewers’ eye level and made from pipe that was strung with a grid of rope through which clothing was threaded.

Brown explained, “The organization of the clothing … form[ed] a solid rectangular surface.”87 The dancers were tasked with dressing and undressing, moving in and out of the garments attached to the ropes, fleeting settlements for their bodies. Audiences studied the activity head-on or ducked down to see the performers hanging below: “Old clothes make new hammocks,” Anna Kisselgoff remarked.88

As in Man Walking, travel in space was task-based. Horizontality impelled a struggle with gravity: “one action impinging on another.”89 This work also relates to Robert Whitman’s Flower (1963), in which Brown and her husband performed an aggressive undressing of each other’s heavily layered clothes. Floor of the Forest circumscribes these actions in relation to a gridded structure, organizing a temporal performance in relation to an object. In the SoHo Weekly News Rob Baker discussed an American Dance Festival performance of the work, emphasizing the work’s “self-containment” as “process, as concept and as a series of specific movements in space.”90 The grid’s first, but not last, appearance in Brown’s work coincided with its ascendance in minimalism as an abstract readymade format. In Floor of the Forest the grid engendered actions with structure and as interactive sculpture. Brown’s repurposing of clothing echoes, among other works of the time, the artist Bas Jan Ader’s photograph All My Clothes (1970).

Figure 3.12 Richard Serra, One Ton Prop (House of Cards), 1969. Lead antimony, four plates, each 48 × 48 × 1 in. (121.92 × 191.92 × 2.54 cm). Collection The Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Grinstein Family. © 2015 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Peter Moore. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York

Figure 3.13 Trisha Brown, Floor of the Forest, 1970. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Figure 3.14 Trisha Brown, Floor of the Forest, 1970. Photograph by Carol Goodden

Figure 3.15 Bas Jan Ader, All My Clothes, 1970. Gelatin silver print, 11 × 14 in. (28 × 35.5 cm), edition of three. © 2016 The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader-Andersen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

Reprised in an October 22, 1971, program that included Accumulation’s premiere at New York University—where Brown was an adjunct assistant professor of dance—she retitled the piece Rummage Sale and Floor of the Forest. A chaotic happening-like clothing sale occurred below the suspended object, where bargaining for clothes with “salespeople tending their tables”91 became a structured improvisation, and viewers became performers.

Reprised at the international exhibition Documenta XII in 2007, in Kassel, Germany—where the piece was prominently located in the Museum Fredericianum—Floor of the Forest was given a curatorial makeover: the choice of new, brightly colored clothing, as threaded through the grid structure, transformed what had originally been a makeshift construction of casual wardrobe discards into a striking, visually dynamic, and aesthetically elegant sculptural object that has been used in subsequent presentations. By contrast, the original, as seen in period photographs, bears the marks of impoverished SoHo living, with the selection of clothing merely functional, holding no appeal to the eye.

Following the 1971 presentation, Brown reflected with Cage-like wonder that imaginatively reframed her art’s perpetuation in everyday life: “The piece is still continuing…. For them it’s a piece of clothing they liked … for me those clothes are artifacts of history.”92 Brown perceived the audience’s actions as dancelike: “Looking at some stranger trying on a kimono that my dear friend Suzushi [Hanayagi] had given me before she was to leave this country, watching the women preen in it, using that gesture of feeling yourself in your new-bought clothes … it was just an incredible experience for me.”93

Occurring within months of Richard Serra’s first site-specific urban sculpture, To Encircle Base Plate Hexagram Right Angles Reversed (1970; figure 3.16), located at 183rd Street and Webster Avenue in the Bronx, “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” and in particular Man Walking—through a logic of indeterminacy—redefined choreography as site-specific, self-contained, and sculptural, delivering choreography to the threshold of conceptual art.

Brown’s location of her work in a “crack” between the sculptural and choreographic expanded in The Stream (1970; figures 3.17 and 3.18), presented October 3, 1970, six months after “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street.” At the daylong event, “ASTRO: An Astrological Celebration,” in New York’s Union Square Park (sponsored by the Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts), Brown edged closer to visual art, experimenting with performance-in-the-absence-of dancers and with choreography as public sculpture.94

Reconstructed for the first time in 2011, on the roof of the Hayward Gallery, London, as part of the 2011 exhibition Laurie Anderson, Trisha Brown, Gordon Matta-Clark: Pioneers of the Downtown Scene, The Stream consists of a bare bones, 34-foot-long troughlike plywood structure with two slanting sides joined by a flat floor on which Brown placed approximately forty pots and pans of different sizes and shapes, each filled with water.95 The Stream invites anyone to “wad[e] through the water or step around pans as if from stone to stone in an actual stream, avoiding water, or racing up and down, climbing on the [construction’s] sides,” a dangerous activity, given the tilting walls, precariously placed pans of water, and gravity.96

Figure 3.16 Richard Serra, To Encircle Base Plate Hexagram Right Angles Reversed, 1970. © 2015 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Peter Moore. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York

Figure 3.17 Trisha Brown, The Stream, 1970. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Figure 3.18 Trisha Brown, The Stream, 1970. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Figure 3.19 Bruce Nauman, Performance Corridor, 1969. Wallboard, wood, 96 × 240 × 20 in. (243.8 × 609.6 × 50.8 cm). © 2015 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Sperone Westwater Gallery, New York

Uncharacteristically literal, The Stream re-creates Brown’s childhood memories: the subtle weight shifting and balance required to play amid streams and rocks, an image she has used to conjure sources for her natural movement language. Inserted into public space, it was a makeshift playground inviting participation. Her incitement of performance by an object compares to Bruce Nauman’s Performance Corridor, created for the 1969 Whitney Museum exhibition Anti-illusion, Procedures/Materials. A plywood construction, 20 feet long by 20 inches wide, it was a sculptural situation directing the audience to assume the role of performer. Nauman said, “The first corridor pieces were about someone else doing the performance … the problem … was to find a way to restrict the situation so that the performance [was] the one I had in mind.”97

Parallels between The Stream and Performance Corridor are significant. Anti-illusion, Procedures/Materials indirectly ushered Brown’s work into the Whitney Museum six months after “ASTRO.” Her April 1970 calendar records a meeting with the Whitney, which was followed by an invitation to appear in its Composer’s Showcase series, a program newly energized by performances that were part of the Anti-illusion exhibition. Mounted in New York just months after Harald Szeemann’s exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form opened in Berne, Anti-illusion (1969) shared with Szeemann’s project the concern to showcase gesture and time through sculptures contingently materialized solely for the duration of a site-specific museum display. Szeemann’s inspiration to “do an exhibition that focuses on behaviors and gestures”98 ultimately explored ephemeral artistic ideas/behaviors, representing artistic processes through sculptures created in situ (not borrowed), that is, works whose “lives” were defined by an exhibition’s temporal limits.

The Whitney’s Anti-illusion exhibition included performances by Richard Serra (with Philip Glass), Bruce Nauman, Steve Reich, Michael Snow, and Keith Sonnier, for which the curator Marcia Tucker coined the name “extended time pieces,” distinguishing these art events from “entertainment.”99 Although sequestered in evening programs requiring a ticket, their inclusion reinforced the exhibition’s recognition of live performance as its touchstone: “Music, film, theater and dance have been considered separate from the plastic arts because they involve time as well as space. They are … impermanent, temporal manifestations whose duration is dependent on the artist, rather than the observer … the plastic arts have begun to share with the performing arts the mobile relational character of single notes to series … or single steps to a total configuration of movement.”100

In Anti-illusion, Procedures/Materials and When Attitudes Become Form (along with the Museum of Modern Art’s 1970 Spaces) curators partnering with artists commissioned ephemeral works of art, a precedent for the rise of performance in the visual art context that underpinned the introduction of Brown’s works to visual art settings. Exhibitions in which sculptures were devised and dismantled compare to “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” (1970), which shared curators’ foregrounding of gesture and time in process-based work that would be categorized as postminimal: sculpture reconceived as transient manifestations of artistic acts and gestures.101

This was the basis for 9 at Leo Castelli (1969) curated by the artist Robert Morris and presented in the remotely located warehouse at 103 West 108th Street, a space secured specifically for this occasion—a project that was influential for Szeemann’s and Tucker’s shows. An essay for Szeemann’s catalog by the artist Scott Burton discussed “the crucially important subject of time in the new art,” queried the status of art whose “installation is synonymous with its existence,” and worried about the “ontological instability” of some works, as compared with “fixed form sculpture [which] does not literally cease to exist when it is in storage.”102 Burton pointed out, “Categories are being eradicated, distinctions blurred to an enormous degree…. The tremendous critical intelligence demanded from the ambitious artist is bringing him closer and closer to the intellectual; art and ideas are becoming indistinguishable … words are looked at, pictures are read, poems are ‘events,’ plastic or visual art is ‘performed.’ In dance the difference between skilled and untrained body movement is dwindling. The only large esthetic distinction remaining is that between art and life; this exhibition reveals how that distinction is fading.”103

Taking as an example Bill Bollinger’s use of a rope to make sculpture, he asks what happens “when it is disassembled? Does it still exist? If so, does it exist as a rope, as potential art, or as art?”104 Robert Morris’s work, subject to alteration in each installation, inspired the comment “Change … may be noticeable only to someone who has seen the work in an earlier state [and so] memory is essential to comprehension.”105 In Artnews’s Summer issue, Burton, reviewing the Anti-illusion exhibition in the wittily titled “Time on Their Hands,” wrote, “As anyone who follows any of the performing arts more than briefly understands, the artist’s own body is not an enduring material.” He noted a “blurr[ing] of traditional distinctions between performing and producing artists; that is, between art as service and art as object. If a work of plastic art can exist as a gesture (and not just the result of a gesture) then critics of the most recent art are right to feel that threatened by the theatricality of temporalized work. The chief characteristic of live performance is that after it is completed, there is nothing left to quantify. The witness is forced to examine his own impressions and thus his own psyche instead of being able to pretend to a formal objectivity…. On the one side of gesture is intention and idea and, on the other, temporal physical action or permanent mark, separate from its motivating idea.”106

James Monte, associate curator of the Anti-illusion exhibition, emphasized, “The radical nature of many works in this exhibition depends … on the fact that the acts of conceiving and placing the pieces takes precedence over the object quality of the works…. The artist must rely on his act, outside of his studio, in a strange environment within a short period of time, to carry the weight of his aesthetic position…. The piece may be determined by its location in a particular place in a particular museum … an integral, inextricable armature necessary for the existence of the work.”107 Brown’s “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street” made site her theater, an “inextricable armature.”

To advertise the Whitney Museum’s “Another Fearless Dance Concert” (1971) Brown selected Carol Goodden’s now iconic photograph of Man Walking for a poster (figure 3.20). A hand-drawn program, backdating Man Walking Down the Side of a Building to 1969, signaled the piece as the model for Walking on the Wall, the main event at the Whitney (figure 3.21). Joined by Leaning Duets II (1971) plus Falling Duets I and II (1968 and 1971) and Skymap (1969), the program, like “Dances in and around 80 Wooster Street,” reflects Brown’s curating of her work in relation to the totality of a context. Presented on the museum’s second floor (denuded of art objects), she located dance on every available wall space: the floor, three adjacent walls, and the ceiling.

Walking on the Wall (1971) reconfigured her vertical walk as a horizontal dance for seven performers, following experiments on the roof of 80 Wooster Street and at the artist Jared Bark’s 155 West Broadway loft, rigged just 2 feet off the floor.108 In anticipation of the track’s installation at the museum, Brown asked architect Bernie Kirschenbaum to contact the offices of Marcel Breuer, the Whitney’s architect, to inquire about the load-bearing capacities of the museum’s gridded ceiling; Brown reported that “Breuer said if a fly landed on it I would get out of the room.”109 Concerned about safety, Rauschenberg contributed to the purchase of seven tracks and harnesses, and even assisted in their installation.110 At the Whitney, Walking on the Wall was performed as a group exercise, requiring the navigation of traffic created by seven dancers (Trisha Brown, Carmen Beuchat, Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, Mark Gabor, Sylvia Palacios, and Steve Paxton) traversing three walls of an open cube.

Figure 3.20 Poster for “Another Fearless Dance Concert,” 1971. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Figure 3.21 Program for “Another Fearless Dance Concert,” 1971. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Figure 3.22 Trisha Brown, Walking on the Wall, Opposites, 1971. Photograph by Carol Goodden

Writers discussed the strange perceptual effect of staring at the tops of dancers’ heads as if one were positioned above them.111 With distance from the horizontal activity, the dancers could be seen climbing ladders and entering harnesses, much as contemporary sculptures’ hardware mechanisms were unconcealed. During repeated and returning walks, a dancer was required to step over the ropes suspending a dancer approaching from the opposite direction,112 making for a performance exemplifying process in time, echoing Anti-illusion’s premises.

Brown’s simplest explorations of gravity were displayed in Leaning Duets II (1971), Falling Duet I (1968), and Falling Duet II (1971; figure 3.23). In the 1968 version, one dancer falls over “like a tree cut down (dead weight), and the other dancer gets (scrambles) underneath and makes a soft landing with the total body surface, not hands. Stand, change roles, and repeat until too tired to continue.”113 Deborah Jowitt described the second version, a duet between Brown and Steve Paxton, as “less friendly, almost painful … involv[ing] lifts and carries in which the lifter … deliberately tosses or tumbles both people to the floor.”114

Figure 3.23 Trisha Brown, Falling Duet II, 1971. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Skymap (1969), a dance that had no danced element, was inspired by Brown’s wish to locate choreography on an inaccessible surface, the gallery’s sixth wall typically used for mobile art’s suspension. She said, “I didn’t want to hang upside down with blood rushing to my head. It was just a way of getting onto the ceiling.”115 Her solution was a voice-recorded sound score: her calm, clinical recitation of a prewritten text, taking listeners on a guided, imagined tour of the United States as a cosmic map, during which she instructed audiences to envision and mentally enact words being moved, tossed, and placed on the ceiling.116

Brown’s idea has several sources: it looks back to Simone Forti’s radical proposition that talking is dance in Halprin’s and Dunn’s workshops. Brown had not seen “the work where Simone Forti read something off a piece of paper and called it a dance,”117 but she had danced an improvisation based on text, in 1963. As part of the YAM Festival, Brown appeared on a May 12–13, 1963, program at the Hardware Theater for Poet’s Playhouse on West Fifty-Fourth Street, presenting 2 Improvisations on the Nuclei for Simone by Jackson Mac Low (1961), a work created for Forti (who had performed it in 1961 at George Maciunas’s short-lived AG Gallery at 925 Madison Avenue).

Figure 3.24 Peter Moore, performance view of Trisha Brown in Two Improvisations on the Nuclei for Simone by Jackson Mac Low (1961), 1963. Photograph © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, NY

Mac Low typed a series of short texts on 3-by 4-inch index cards, sentences generated by chance procedures to inspire improvisations;118 the cards—what Mac Low referred to as an “action pack”—originated in his play The Marrying Maiden: A Play of Changes (1960), performed by the Living Theater (with music by John Cage). For that event he produced 1,200 cards, instructions for random disruptions of the play’s narrative script. He reduced the number to 108 for Forti, and Brown’s 1963 rendition included only 3 cards.119

Photographer Peter Moore documented Brown’s performance, about which she recalled, “I was in such fear … such dread dread dread … I started out by saying this dance is called Nuclei for Simone Forti. I’m not Simone Forti. Then I combusted somehow, I was sitting on a chair … I got up on it and I was sort of squatting on the … heavy … well-built chair—and I leaned over and I licked the back of the chair,” as is seen in one of a series of Peter Moore’s photographs. Brown continued, “That was insane … It was beautiful, but it scared me to death … because you have nothing to hide behind. And you know the audience is squirming.”120

Figure 3.25 Postcard sent by Earle Brown to Trisha Brown, 1965. Trisha Brown Archive © The Earle Brown Music Foundation