Читать книгу Trisha Brown - Susan Rosenberg - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSeeing the Score

Trillium (1962)

1

Hers was the most original material. Could we suggest she try and make a dance?— Bessie Schönberg1

On March 13, 1962, Trisha Brown made her choreographic debut with her first professionally presented choreography: Trillium (1962).2 It was included in an interdisciplinary Poet’s Festival at New York’s Maidman Playhouse on Forty-Second Street: the event featured experimental music, happenings, visual art, and dance by artists who embraced composer John Cage’s ideas.3 Four months later, she presented the dance to be assessed for possible inclusion in a performance scheduled to take place at the center of the modern dance establishment: the American Dance Festival (ADF) at Connecticut College in New London. On July 30, she was one of sixty dancers who auditioned for an August 7, 1962, juried “Young Choreographers” program that aimed to showcase work by representatives of America’s most important dance departments—those at Bard College, Bennington College, Juilliard, and the University of Wisconsin—along with one artist from Sweden and two from New York, including Trisha Brown.

At Maidman Playhouse, Trillium—a dance executed according to the three simple instructions “stand, sit and lie down”—was singled out as “the high point of the evening … a taut construction and a nice performance.”4 The ADF jury (Louis Horst, Bill Bales, Bessie Schönberg, and the festival’s director, Jeannette Schlottmann) initially rejected it, later reversing their decision.5 This owed to Bessie Schönberg’s change of heart, recorded in a note to Schlottmann: “Last night I must have been too tired to think straight. But Trillium kept haunting my early hours. Now if we permit Nancy to work on her eccentricities and show [in] the finale … why can’t the ‘Trillium’ girl not enjoy the same privilege? Hers was the most original material. Could we suggest she try and make a dance?”6

Brown has revisited this controversy on many occasions, deriving from it an iconic avant-garde origin story of misunderstanding, a scandale of refusal, and ultimately acceptance and triumph: “I think some stories are emblematic of how I got where I am and that’s why I go back to them.”7 In a letter to her friend Yvonne Rainer, she explained that the dance had been rejected for its absence of form (choreography) and its music. She also affirmed her steadfast defense of her work: with other students’ support, jurors at ADF agreed to include her work on the “Young Choreographers” program, although Brown refused to eliminate Trillium’s musical accompaniment as a condition of its acceptance.

This contretemps, Brown told Rainer, marked an unprecedented student rebellion against the festival’s authorities. “There was something quite extraordinary that happened for a week … Turned down. No form,” she wrote. “Louis H. said it was dull and acrobatic and that I was barking up the wrong tree in NY… and I am irresponsible [and] without dignity … And music made him sick and was not beautiful. But the students, Sally Stackhouse in the lead, started a petition and hounded the judges [who] reconvened and said, ‘Yes, but no music’—so I said no. So they reconvened and [I] said Yes. And I did do it. The petition was an event … [the] first time the students ever spoke up at this place. The endless discussions killed me—no form so it’s not a dance. And what does it mean?”8

Sally (now Sarah) Stackhouse recalled, “I was there at the audition.… Her Trillium was so stunning … inventive of course, but also spatially such a contrast from what I was used to that it latched itself into my mind. The movement was … danced with all the skill and beauty one would expect.… I was shocked that it wasn’t accepted and then really annoyed…. I must have made a big enough fuss that finally Bessie Schönberg (1906–1997) agreed to meet in the cafeteria with Trisha to let her know why the committee had rejected her piece. I don’t know who else was on the committee but probably all traditionalists. Trisha told me … that Bessie said there was no structure to the solo.”9

Speaking in 1993 to Charles Reinhart (ADF’s director from 1968 to 2011), Brown recounted that Schönberg “didn’t understand the logic of how I organized this dance … she made the assumption that there was none.”10 Brown remembered sitting “at the table in the Connecticut College cafeteria” and Schönberg saying, “You just can’t take things and put them together in an order, any old order, like this pepper shaker and this ashtray and this napkin, and, well … this is looking rather nice.”11 In Brown’s telling, Schönberg changed her opinion, realizing that Trillium’s lack of structure was apparent, not actual. It was choreographed. Stackhouse described the meeting, “in the midst of which [Schönberg] stopped—and got quiet while she observed what she had done—and her face changed—with recognition—that there was an organization! Just not what she expected. And so—she did a 180 and accepted Trillium: that was a powerful encounter of the flexible, enlightened mind of a teacher and the marvelous work of the brilliant young Trisha Brown.”12

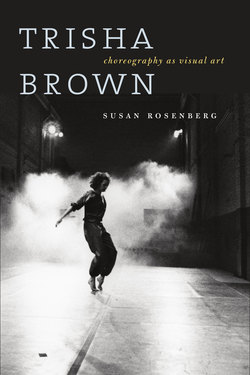

Figure 1.1 Trisha Brown, Trillium, 1962. Photograph © 1964 Al Giese

At ADF, Brown was an emissary of experimental dance and new pedagogical approaches to choreographic composition, outcomes of her recent participation in two post-Bauhausian interdisciplinary experimental workshops: that of Ann Halprin (b. 1920) in Kentfield, California, in the summer of 1960 (focused on improvisation) and that of Robert Ellis Dunn (1928–1996) in New York in the winter of 1961 (focused on choreographic composition).13 Trillium integrates Halprin’s use of task instructions and improvisation with John Cage’s methods, absorbed through Dunn’s class, taught (at Cage’s behest) to transmit Cage’s ideas on music’s composition to choreographers.

Embodied in Trillium are artistic concerns that eluded ADF’s jurors, including the dance’s basis in three task behaviors—stand, sit, and lie down—a tripartite composition derived from Brown’s memories (from her upbringing in Aberdeen, Washington) of the wild three-petaled trillium flower. Executed in an unplanned, changing order, without transitions, Trillium included these actions as well as extemporaneous dancing, the latter related to its music, which proved so offensive to ADF jurors: a recording of Simone Forti’s vocal improvisations, “a composite of all the different sounds that could come out of [her] mouth, including pitches, screeching and scraping.”14

Brown’s introduction of an experimental work to a context other to it challenged assumptions, predispositions, and prejudices of modern dance, an act closely related to what came to be known in the 1970s as the art of “institutional critique.”15 This opening of Trillium to judgment by modern dance experts suggests Brown’s wish to participate in artistic experimentalism in New York without relinquishing an interest in conventional modern dance models. The story also intriguingly predicts Brown’s later career, when, after two decades of showing her work only in nontraditional or art world contexts, she embraced the conventional institutional setting associated with dancing: the theatrical stage.

Trillium evidences Brown’s tenacious commitment to the discipline of choreography, instilled in her by her teachers at Mills College, in Oakland, California: Eleanor Lauer (1915–1986) and Rebecca Fuller (b. 1929). Both based their composition classes on the writings of Louis Horst (1884–1964), Martha Graham’s musical assistant and the most important pedagogue of modern dance composition in the 1950s.16 Brown studied directly with him over three summers (1956, 1959, and 1961) at ADF.17 Horst’s insistence on choreography as based in repeatable formal structures became Brown’s standard against which she measured her work.

While she would reject Horst’s emphasis on choreography’s subservience to music, she nonetheless referenced Horst’s impact many times, even as she was applying Halprin’s and Cage’s ideas to choreography in Robert Dunn’s class, which he devised, in part, to challenge the dominance of Horst’s methods.18 To her formative education in Horst’s teachings she grafted John Cage’s different ideas about a composition’s structuring. Rather than take a musical score as her choreography’s inspiration, Brown adopted Cage’s approach: much as he established the parameters or (durational) frames that enabled sound material to be heard and recognized as music, Brown applied three tasks as a structure to generate movement as material, producing a new understanding of what constitutes a dance.

Her 1962 visit to ADF was her fourth. Now she faced a jury. “The reason that I went so many times,” she said, “was that Mr. Louis Horst was unforgiving about how I was making choreographies then. And he rejected me more or less, partially. So that’s why I went back, to make an impression on him about my kind of dancing and try to link it up with his kind of structured choreographies.”19 Brown’s inclusion in the “Young Choreographers” program was a victory for her, in that she was seeking validation for her experimental composition, the legitimizing imprimatur of choreography. In the Robert Dunn workshop, where Trillium was created, conventional ideas about dance movement and choreographic composition were discarded—in what some might identify as an anti-dance position. Brown recalled that in Dunn’s class judgment was eschewed, in alignment with Cage’s approach: “The students were inventing forms rather than using the traditional theme and development or narrative, and the discussion that followed applied non-evaluative criticism to the movement itself, and the choreographic structure, as well as investigating the disparity between the two simultaneous experiences, what the artist was making and what the audience saw.”20

Brown’s point echoes one made by John Cage, in which he differentiated a work’s maker from its viewer, a point that is also relevant to considering Brown’s dual siting of her dance in New York and New London and to content-based meanings inspirational to her dance (but not necessarily apprehensible, or meant to be transparent to its audience): “A composer knows his work as a woodsman knows a path he has traced and retraced, while a listener is confronted by the same work as one is in the woods by a plant he has never seen before.”21 Brown’s “plant,” presented to two different listeners/lookers, invited New York critics and America’s reigning modern dance experts to weigh in on the very question that Dunn’s teaching of Cage’s ideas had put into play: “What is choreography? What is dance?”

Figure 1.2 Trisha Brown, Mills College Dance Studio, 1964. Photograph, Trisha Brown Archive, New York

Trillium’s “transplantation” to two different contexts is not an element external to it (part of its reception), but a concept Brown instilled in her dance at the outset. This is obvious from an examination of what is known about Trillium: Brown’s ideas for its choreography and performance, as recorded in two photographs, the firsthand testimony of Brown’s peers, two published reviews, and a 1964 photograph of Brown rehearsing in a studio at Mills College. It captures her in the air, elevated in a horizontal position above the ground—the hallmark movement in her controversial dance.

Steve Paxton, a participant in Dunn’s workshop, who practiced improvisation with Brown and Simone Forti outside of the class, offered important testimony about Trillium. In a 1981 interview, he interpreted its title’s relation to its content (not its form), recalling, “Trisha told me that a trillium was a flower that she had found in the wood…. She said she used to pick them … but by the time she got home, they would be wilted and faded … that’s what she thought about movement—it was wild, it was something that lived in the air.”22 Paxton, a master of improvisational performance—dance that is “not historical. Not even a second ago”—saw Trillium as emblematic of Brown’s love of dancing’s unruly ephemerality.23

Paxton’s attachment to, and investment in, improvisation’s creative potential informed his retrospective reading of Trillium as an elegy for the fading perfume of the wildflower—of movement and dancing. Other meanings of Paxton’s story emerge if its valence shifts from the issue of movement’s evanescence to the problem of choreography’s structural survival. This is what riveted Brown and inspired Trillium’s concept. Transplantation, an idea imbued in Trillium’s story, was an act that Brown made real, re-siting her dance from one context—“natural” and organic to it to another that was “domesticated” and defined by convention/tradition. In actualizing Trillium’s concepts of decontextualization and transplantation, Brown revealed a precociously acute understanding of how an institutional context, or performance situation, affects the way a choreography is seen and how it produces its meaning, as well as its import.

Brown came to join Dunn’s class through the recommendations of Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer.24 Having learned of the Fall 1960 workshop being offered by Robert Dunn, a composer and former musical assistant to Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham (at whose space on Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue Dunn’s class was taught), they encouraged Brown to relocate to New York. In the winter of 1961 she traveled to the city by Greyhound bus to join Dunn’s class, living for a short time at a YWCA near the Port Authority, then with family members on Long Island, and finally in the borrowed apartment of Steve Paxton at 529 Broome Street.

Brown’s first appearance as a performer in New York was in Robert Whitman’s March 1961 Mouth at New York’s Reuben Gallery, a venue known as the first to showcase “happenings” (the expansion of painterly ideas with new materials and the body into three-dimensional space, environment, and time). Brown recalled, “Someone said, ‘Would you like to be in a happening?’ I said, ‘What is a happening?’ I found my way into the midst of a Robert Whitman happening across the Bowery. Yes, middle class values, very young, 23, maybe 22, going into a small, dilapidated space like the lower floor of a tenement building.”25 Brown’s choice of Trillium’s title (based on a living object/image) relates to titles’ function in Whitman’s visually poetic, imagistic works, which he called “moving sculpture.”26

Writing about Flower (1963)—in which Brown also performed—a critic focused on his “distinctive form … massive and quiet, primitive and sensuous, integrated by a central idea in which all the occurrences relate to the title of the piece.”27 Whitman celebrated the roles of title and image in his 1966 Prune Flat: “Titles are always appropriate and … usually very important. They do acquire, if they have any sense, you know, they become a metaphor, part of the image of the piece.”28 In his abstract theater, Whitman said, “I conceive of each piece as one image, and by the end of the piece the image is revealed through exposure of its different aspects.”29

He also said about his performances that “you might think of them … as an object. An object of consideration for the mind.”30 In a 2002 conversation Brown mirrored back to Whitman his notion of a poetic image as a work’s unifying principle and basis for its temporal unfolding, recalling Trillium: “It’s about realizing an image, and it’s non-verbal.”31

She too worked from an image to an abstract structure, transposing the flower’s three-part structure to a three-part composition. Attributing her approach to Halprin’s teachings, she conveyed how Trillium distills and encapsulates in her work a particular moment in her training in a fashion that was a precise as well as a strikingly literal response to innovations then being introduced to contemporary dance. Brown identified the use of “task” and “improvisation” as specific to Halprin’s workshop. “Anna [Halprin],” Brown said, “had identified a normal task as a form for performing…. Her work is primarily improvisational. Nevertheless a task was something quite ordinary, like sweep the floor, stack cardboard boxes or dress and undress. That notion was like a found form, and it came into New York through this class.”32

For Halprin, tasks were “systems that would knock out cause and effect,”33 “open[ing] up the possibility that movement can come from a more functional basis.”34 Task is a tool for generating movement that appears to be objective by avoiding subjective compositional decisions, including approaches to choreographing based on narrative, characterization, or self-expression. Task enables movements’ discovery in the act of improvisation—not by imitating already-given movement techniques or forms.

Brown recalled Trillium’s making as “working in a studio on a movement exploration of traversing the three positions, sitting, standing and lying. I broke these actions down into their basic mechanical structure, finding the places of rest, power, momentum and peculiarity.”35 Describing Trillium as a “structured improvisation,”36 she invoked Simone Forti’s influence—her technique for improvising movement in relation to scores and structures, practiced outside of Dunn’s workshop. Describing Trillium as a “kinesthetic piece,”37 she credited Halprin’s anatomically based teachings, the legacy of Halprin’s teacher, Margaret H’Doubler (1889–1982).38 Retrospectively describing it as a “serial composition,” she recognized its connections to mid-1960s art and music.39

To Halprin’s use of task Brown introduced John Cage’s compositional methods, delivered to her by Robert Dunn, who had studied in Cage’s class at the New School for Social Research in New York (1958–1960), a laboratory that spawned the rise of “happenings,” Fluxus, and other performative practices.40 Dunn was especially alert to one of Cage’s newest principles: indeterminacy. While offering his workshop, he undertook, at Cage’s invitation, the editing of the first published catalog of Cage’s musical scores. Cage’s foreword to this slim 1962 volume commended Dunn’s organization of his oeuvre according to a logic that was not chronological, but defined by “categories of sound production … to clarif[y] differences in performance requirements, which Cage delineated.”41 The catalog brought Cage’s work up to date—for example, including scores since 1958 that Cage described as “composition indeterminate of performance.”42

Cage had introduced his concept of indeterminacy in a 1958 lecture in Darmstadt, Germany, in lectures and performances in the United States, and in the publication of his collected writings, Silence (1961). He related the idea to that of an experimental composition in “Composition as Process: II Indeterminacy”: “This is a lecture on composition which is indeterminate with respect to its performance. That composition is necessarily experimental. An experimental action is one the outcome of which is not foreseen…. A performance of a composition which is indeterminate of its performance is necessarily unique. It cannot be repeated. When performed for a second time, the outcome is other than it was.”43

Dunn implied Brown’s acute response to his delivery of Cage’s ideas in the workshop: “The Trisha Brown I remember from the 1960s was quiet, keen and penetrating…. It is very possible that she, more than anyone else, had the mental grasp and subtlety to retain the more recondite points I was trying to make at that time; for example, the insistence on a constant renovation of working methods in the contribution that could make [a] permanent continuing revolution, both in form and content.”44 Trillium manifests this form–content relation joining experimental composition, indeterminacy, and a further Cagean principle: the organization of sounds side-by-side without transitions.

Trillium’s three movement tasks reveal Brown’s penchant for reductive simplicity: she narrowed her choices to the most elemental forms through which the body encounters space. “Task” enabled her to overcome a challenge of choreographing in the absence of a movement vocabulary, a problem that she later said had limited her creativity early in her career when “the mode of teaching choreography was to use the Louis Horst forms of theme and development. I never understood it. I always had difficulty because I hadn’t developed my own source of movement so the restrictions of the choreographic forms just got in my way.”45 This 1972 statement, indicative of Brown’s interest in choreographic forms (and uncertainty as to the path beyond options for generating movement provided by Halprin and Dunn) is contemporaneous with her study of this very issue in her “Equipment Dances,” discussed in chapter 3.

In Trillium Brown’s set tasks were devised for execution in an indeterminate relationship to one another: each of its performances was a repetition of choreographed tasks and yet unique, owing to the tasks’ changing order. Brown was Trillium’s creator and performer: she separated her choreographic contribution—the score—from her role of realizing its instructions, in dancing that required cognitive on-the-spot choices about the tasks’ fluctuating arrangement. Brown’s randomizing of movements’ order refreshed—by defying—a basic tenet of modern dance composition: its dependence on music’s A-B-A structure, which Horst called “the most deeply instinctual aesthetic form: a beginning, a middle and an end…. It is the three-part form, which is the rhythm of the natural drum beat, the pattern of the common limerick verse, and also the usual basis for serious musical composition of any dimension, from a simple song to a complex symphony.”46

A-B-A produces theme and variation. Trillium’s open-ended composition enabled a different organization. As Halprin explained, “Usually in a dance program the audience views a product. By that I mean a dance demonstration, which has been worked over and fixed into a static form. This program has a new form. The form is not a static product but is a form to be found in the process. This focus demands a different way of looking at dance.”47 Trillium is an iterative artwork incorporating stable, unchanging elements and components that can be rearranged in each performance. Brown’s commitment to a dynamic relationship between fixity and variability served to keep movement alive in the moment: “One of the problems I discovered during Judson,” she said, “was that I had a hard time setting material: capturing movement, recalling it and doing it again. I could do it the first time. I could remember the image that caused me to do it, but if I codified it, I lost it.”48

A final key to Trillium’s composition lies in Brown’s refusal to create transitional movements linking one task to another, an evasion of traditional dance phrasing that avoided movements’ rigidifying into, repeatable, stable, and unchanging forms. Trillium’s unit-after-unit organization of movement material compares to Cage’s treatment of sounds as “material”: his location of sound outside of preexisting categories that filter how they are experienced so as to allow a new way of hearing music as sound material—or in the case of dance, a way of seeing movement as material. He introduced the idea of sounds’ juxtaposition without transitions in “History of Experimental Music”: “[Composers] were getting rid of glue…. Where people had felt the necessity to stick sounds together to make a continuity, we … felt the opposite necessity to get rid of the glue so that sounds would be themselves.”49

Erasing “the glue” has different results in music than it does in dance, where it is an unachievable ideal: one has to get from point A to point B. In Trillium an impossible instruction incited improvisational effects in moving from one task to another. Structured elements contained these effects; improvisational moments remained repeatable set elements of the composition, expressing Brown’s vision of choreography as an objective structuring of intention. Steps are an arbitrary element of artistic decision making, subordinate to, and inserted into, the fabric of choreography: her model, based on Cage’s, deliberately avoided their introduction, and this remained, for Brown, an ongoing artistic problem. “Traveling steps have always stymied me,” she said. “Traveling steps are what dancers use to get from Place A to Place B on the stage. I have always walked. It would embarrass me to hop over there.”50

Erasing movement transitions produced spontaneous improvisation. Speaking to Deborah Jowitt about her early 1960s work, Brown said, “I always kept certain doors open to go through if I had the courage. I wanted to resolve things in performance, to have that open-endedness for brilliance times ten.”51 Trillium produced volatile dancing. Brown cantilevered off the floor into handstands and hovered above the ground: “I could stand, sit or lie down, and ended up levitating.”52 “I went over and over the material,” she said, “eventually accelerating and mixing it up to the degree that lying down was done in the air.”53

Brown’s claim of levitation might seem outrageous, if not corroborated by two participants in Dunn’s workshop, Aileen Passloff and Elaine Summers, and two especially credentialed eyewitnesses: Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer, who were both dedicated to the demystification of dance virtuosity. Brown recalled, “The choreographer Aileen Passloff happened to come into the studio and just stood there in the doorway watching me. I realized I should stop because she was renting the studio … [I said] ‘I’m sorry. I’ll get out.’ She said, ‘do you know what you were doing?’ And I said, ‘well I know what I was instructing myself to do in the improvisations.’ And she said, ‘you were flying.’”54 Elaine Summers said, “When I saw Trillium I decided that Trisha didn’t know about gravity and therefore gravity had no hold on her.”55

These descriptions are reminiscent of recorded stories verifying Brown’s levitation on Halprin’s deck in the summer of 1960. Forti remembered: “She was holding a broom in her hand. She thrust it straight out ahead without letting go of the handle. And she thrust it out with such force that the momentum carried her whole body through the air. I still have that image of that broom and Trisha right out in space, traveling in a straight line three feet off the ground.”56 Rainer said, “She had this big push broom and she would push it a few feet with tremendous force and then hang onto the handle. Her body would be almost horizontal as it flew after the broom. Amazing looking cause and effect—her arm shooting out, the broom shooting out and then her body shooting out in forward propulsion.”57 Brown’s levitation is confirmed by a 1964 photograph (see figure 1.2), taken in a Mills College dance studio and witnessed by Brown’s teacher and friend, Rebecca Fuller.58

This act of concentrated kinesthetic intelligence exists as a trace in Bruce Nauman’s double-exposed photograph, Failing to Levitate in the Studio (1966). It records the impossibility—not the actuality—of placing mind over matter. Given Nauman’s acquaintance with Meredith Monk (who later joined Dunn’s class) and his awareness of Halprin’s work, might his photograph echo the passed-on story of Brown’s legendary levitations? A true myth of Brown’s artistic biography and a touchstone for her subsequent investigations of gravity and gravitylessness, her uncanny physical virtuosity and understanding of the body’s logic have a rational explanation. For a time, her highly athletic older brother, Gordon Brown, a high school football and basketball star, “was training [her] to go into the Olympics as a pole-vaulter in the backyard. The yard was slanted and he had me starting on the high side. His theory was that if I could get into an arcane area of sports, and I was good at it, then I could beat the Russians.”59

Figure 1.3 Bruce Nauman, Failing to Levitate in the Studio, 1966, black-and-white photograph, 20 × 24 in. (50.8 × 61 cm). © 2015 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery

A testament to Brown’s athletic prowess, the story references vestiges of movement memories preceding Trillium’s trademark levitation. Indeed, Yvonne Rainer recognized Trillium as re-creating the earlier levitation on Halprin’s deck, suggesting that Brown’s dance returned to, and memorialized, experiences from Halprin’s class: “Two years later (i.e., in New York) Trisha would duplicate the move, without the broom, in her solo Trillium.”60

Figure 1.4 Audiotape box of Simone Forti sound score for Trillium, 1962. Trisha Brown Archive, New York

The idea of re-creating or reinstantiating vestiges of improvisational events from Halprin’s workshop is central to Brown’s choice of Trillium’s sound score and key to the dance’s meaning. Recording Forti’s improvised vocalizations on reel-to-reel tape (still a relatively rare technology in the early 1960s),61 Brown consolidated, through one example, a memory but also a concept: her poignant experiences of many fleeting extemporaneous performance moments (witnessed in Halprin’s workshop), whose disappearance she mourned, stating, “It bothered me that all of this material was going into the ether.”62 By having Forti replicate a vocal improvisation that had made a strong impression that summer, she preserved one instance among many lost moments of movement and sound improvisations, synecdochically representing improvisation as an idea; indeed, today the sole concrete record and remnant of Trillium resides both in the three words, its task instructions, and in a physical artifact: the audio reel of its original sound accompaniment.

The experimental sound score reflects Brown’s response to Simone Forti’s extraordinary vocal improvisations and exposure to the music of Terry Riley and La Monte Young, followers of John Cage, who were accompanists, as well as participants, in Halprin’s workshop. Her choice of the score for Trillium may also have been reinforced by her November 1961 performance in Yoko Ono’s Carnegie Recital Hall concert, which featured music, movement, objects, sound, and action. Brown remembered, “I was invited to be in something that was some kind of a theater piece that was being done at Carnegie Hall with … a woman named Yoko Ono. I had a specific thing I had to do in dance, but she was making orgasmic sounds over a microphone out of sight. I didn’t know where she was. And another dancer was stacking cardboard boxes up. I had no idea what this was, but you know, Carnegie Hall certainly validated my presence in New York City to my parents at this point.”63

Accompanying a “rhythmic background of repeated syllables [and] a tape recording of moans and words spoken backward was an aria of high-pitched wails sung by Ono.”64 The orgasmic sounds Brown recalled—the element of the concert that is most often described—derived from Ono’s childhood memory of hearing the noise of a baby’s birth. Re-creating the sounds and manipulating them electronically so that they played backward, she proceeded to learn the piece, repeating these sounds as a live vocal performance.65

Ono’s work anticipates Brown’s use of Forti’s experimental vocal music, based on memories, such as “Simone Forti lying in bed, singing Italian arias” and Forti improvising in Halprin’s class: the image of “Simone with a garden pointed at her mouth, singing a beautiful Italian aria into the hose that is issuing water into her mouth simultaneously.”66 Brown said, “I didn’t know what category of behavior that went into. Simone brought a very accomplished level of improvisation back to New York.”67 “Simone did absolutely extraordinary things. When you see something that incredible and perceive it as poetic.”68

To comprehend the score’s symbolic function requires revisiting further aspects of Brown’s experience in Halprin’s class: how and why she arrived there, her perceptions and experiences of Halprin’s teachings, and ultimately the process by which she chose to introduce improvisational elements in her first choreographic composition.

At Mills College, Brown had studied traditional modern dance and traditional modern choreographic composition according to Louis Horst’s methods. The school’s Music Department was historically more progressive than its Dance Department; John Cage had taught there in 1954 and provided music for Horror Dream (1947), a choreography-for-film by the founder of the Mills College Dance Department, Marian van Tuyl (1907–1987). The Music Department influenced dance teachers with whom Brown studied: Eleanor Lauer, Rebecca Fuller, and the musical accompanist Doris Dennison (1908–2009), who had worked with Cage in the 1950s.

Figure 1.5 “Percussion Band,” John Cage and Marian van Tuyl, Oakland Tribune, 1941. Photograph © Don McDonagh, Special Collection, F. W. Olin Library, Mills College, Oakland, California

Brown fondly remembers attending Sunday dinners at the home of the émigré composer and director of the Mills Music Department, Darius Milhaud (1892–1974), who in the 1920s, in Paris, had been a member of “Les Six,” the most avant-garde musical composers of the day. During these gatherings Brown would assist his wife, the librettist Madeleine Milhaud, in the kitchen.69 When Brown studied dance off-campus, she did not go to Halprin’s workshop, as did other students, but instead went to Ruth Beckford’s studio.70 She claimed that at Mills improvisation was considered taboo, a point she made by paraphrasing Horst: “Louis Horst thought it [improvisation] was comparable to turning out the lights and announcing happy hour.”71

After graduation Brown became a dance instructor at Reed College: A 1958 college press release announced that “Patricia Brown, an outstanding young choreographer and dancer from Mills College, will conduct a series of classes of young children of varying groups during the day, and separate classes for beginning and advanced students during the evenings. Miss Brown will continue during the academic year as an instructor in physical education.”72 Reed’s Dance Department was part of the Division of the Humanities and Arts in 1949; in 1953, it moved to the Department of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, remaining there until 1967, when it came under the umbrella of the Department of Arts.

Brown’s decision to teach at Reed was influenced by the example of her teachers at Mills, especially van Tuyl, who was hired for a tenured academic position in 1938 in the midst of the Great Depression. Both Van Tuyl and Lauer described themselves as choreographers/dancers torn between the security of academia and the wish for recognition in the professional context of New York dance.73 In light of Janice Ross’s study of the split between academic dance and concert dance in 1950s America, these women’s desire to bridge this divide is exceptional and had an impact on Brown’s outlook as she embarked on her career.74

Mills College emphasized teaching, based on the 1950s supposition that women would want to balance dance with family life and children. Teaching was “an auxiliary skill, after graduation, to reinforce my conventional life,” Brown said. “Remember, this was the 1950s, a very closed era. I had been brought up to think of marriage, being a mother and a housewife as the most important thing.”75 Nevertheless, at Mills she was surrounded by impressive role models, “Doris Dennison, Becky Fuller, Marian van Tuyl and Eleanor Lauer … women of achievement.”76

At Reed, Brown said her students had no dance training. Liz Thompson, a nineteen-year-old Reed College student when she first met Brown (and who performed in Brown’s Roof Piece, 1971, years before they worked together when Thompson became director of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in 1980, a post that enabled her to become a major supporter of Brown’s work, as is discussed in chapter 9), recalled Brown teaching a highly eccentric version of Graham’s technique and alignment.77 Brown said she mostly used improvisation. This led her to seek the knowledge necessary to do her job, by studying with Halprin. She recalled, “The nature of the student body [at Reed] at the time was irreverence mixed with a complete lack of training and discipline.”78 Faced with teaching dancers “who didn’t fall into the categories of dance I had been taught at Mills,” she began improvising.79 “I needed to give them a dance experience without having to rely on these kinds of techniques and … so that’s why I went to Ann.”80

Figure 1.6 1960 Ann Halprin Summer Workshop participants at the dance deck in Kentfield, California. From left to right, standing, Shirley Ririe, Trisha Brown, June Ekman, Sunni Bloland, Ann Halprin, Lisa Strauss, Paul Pera, Willis Ward; seated: Jerrie Glover, Ruth Emerson, unknown, Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, A. A. Leath, unknown, John Graham. Anna Halprin/Papers/Museum of Performance and Design, San Francisco. Photograph © Lawrence Halprin, provided by Museum of Performance and Design

Still, Brown was ambivalent, her irresoluteness suggested in a photograph of the Halprin summer 1960 workshop participants. Brown stands far to the left of the group with her long hair hanging over her face, covering it. She described the image as “the family picture at the end of the whole thing,” and had combed her hair down over her face because “I wasn’t too sure about this group.”81 Yvonne Rainer noted, “In a group photo of the Halprin workshop participants Trisha is nowhere to be found…. She is the standing figure whose hair is pulled over her face and tied around her neck.”82

Over the years, Brown discussed her experience at Halprin’s with a few stories told mostly for humor and to convey her disorientation and fear—for example, describing A. A. Leath, a member of Halprin’s company (the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, founded in 1955), circling around her making loud grunting sounds. Brown said, “I just remember thinking that this whole thing was maybe even creepy. I kept telling myself just keep on participating at the level you can.”83 Simone Forti’s vocal and dance improvisations made the most significant impression on her. It was one such example that she solicited and recorded as Trillium’s soundtrack, preserving an exemplary instance of the kind of improvisational activity that informed Brown’s attitude toward Halprin’s teachings—what she perceived as both their deficiency and their potential: improvisation’s resistance to repetition as choreography but its potential to produce powerful, memorable images.

Each evening, Halprin had her students write her a letter; Brown said, “I would write her only one thing: ‘I would like to learn choreography,’ or ‘I would like to study choreography’; ‘When do we get to make dances?’ Her response to me was that she didn’t feel the group was ready to do that, and so I felt thwarted.”84 Brown compared this with her previous studies: “I didn’t have a sense that there was a curriculum or a structure or a sequence in the classes … some understanding of what we could do through improvisation. Ann may have had some game plan, but I wasn’t informed of it … if I said to one of my professors at Mills, I don’t understand this point of choreography, he had an answer for me and I remember the answers. Then I realized that she doesn’t do choreography, she improvises.”85 If these statements seem tainted by the years separating Brown’s later career from its beginnings, she expressed the same sentiments in a 1964 letter to Yvonne Rainer during a period (1963–1964) when Brown had briefly returned to California, taught classes at Mills College, and participated intermittently in Halprin’s workshops. In that letter, Brown complained to Rainer, “Ann has no sense of structure.”86

Ambivalence about improvisation’s arbitrary randomness—but also recognition of its potent lyricism—informed Trillium’s framing of improvisation in a simple structure. Seen through Brown’s vision of a wild-flower’s expiration, her “choreographing” (by reprising and re-creating) an example of one fleeting jewel-like memory of a vocal improvisation from Halprin’s workshop as her work’s sound score—together with her re-realization of that initial levitation on Halprin’s outdoor dance deck—counteracted her painful experience of lost, evanescent, onetime improvisational events. Trillium thus can be seen as a choreographic rendition of the theme of memento mori, a transposition to choreography of a motif common to seventeenth-century still-life paintings featuring exotic floral specimens (never wildflowers)87 and meant to inspire reflection on the vanity of life. Brown distilled the theme to suggest (as well as contest) the notion that choreographic art might be a vain pursuit, given dance’s fragility and ephemerality, to which she also referred in her image of the wild trillium flower.

Highlighting memory, loss, and mourning, Brown contrasts the fleeting, evanescent, nature of improvisation with choreography’s structural fixity and durability. Well before twenty-first-century dance historians and theorists came to define choreography of the modern period as “charged with a lament verging on mourning,”88 Brown, with startling clarity and formal rigor, questioned whether transient memory and improvisation, as represented in sound and movement, endure through choreography’s tangible, permanent elements (tasks). If the form and format of a temporal art form are contrived according to a fixed logic—encompassed in an image/object and in simple language—might choreography endure?

Brown’s dance objectifies transitory memory and dancing through artistic principles, a context unto itself. Its improvisational moments are contained, produced by an approach still marked by conventions and traditions of choreographic artistry—structure—while her work’s integrity and potential to thrive or die become measurable in relation to a context and to a particular historical moment in the dance’s reception. The recovered story of its provocation of an artistic conflict between experimentation and tradition secures for Trillium an important role in dance history, one deserving remembrance and acknowledgment.89

Identifying disappearance as intrinsic to improvisation, Brown imagines choreography as removed from any absolute or essentialized definition of ephemerality as an intractable attribute of choreography. The dance theorist André Lepecki writes, “If movement-as-the-imperceptible is what leads the dancing body into becoming an endless series of formal dissolutions, how can one account for that which endures in dance? How does one make dance stay around, or create an economy of perception aimed specifically at its passing away?”90 Brown’s Trillium responds to this artistic problem, insisting on improvisation as an ineffable, uniquely original but repeatable element occurring within a fixed choreographic score.

Lepecki’s view that “the casting of dance as ephemeral, and the casting of that ephemerality as problematic, is already the temporal enframing of dance by the choreographic”91 is articulated through Trillium’s presentation of a differential relationship between choreography and improvisation. For Brown the latter is always ephemeral, as contrasted with the durable elements of choreography. Her self-consciously crafted thematization of the memento mori theorizes in itself the notion of improvisation (not choreography) as “an art of self-erasure.”92 This transforms into a concept Lepecki’s belief that “[once] the question of dance’s presence began to be formulated as loss and temporal paradox, dance was transformed into hauntology and choreography cast as mourning.”93

When Trillium was presented in New York and New London, its dynamic of formalized task, chorographic logic, and indeterminate performance went unseen. Its title’s meaning remained a private element of its inspiration and meaning, whose implications for its author/choreographer differed from the audience’s experience. Spontaneity, not structure, was perceived to be Trillium’s prime attribute. As Steve Paxton wrote many years later, “I have after all seen Trisha Brown in Trillium (a pretty flower that grows in the woods) and been much moved…. The magic is not in the instruction.”94

Likewise the title’s magic, as related to Trillium’s composition/meaning, went unremarked by critics. Jill Johnston drew attention to Brown’s uncommon effervescence as a dancer and performer: her natural ability to evade gravity with a mixture of athleticism, restrained composure, and grace. She wrote, “Trisha Brown’s solo Trillium is spontaneous in another way. The short dance grows, flowers of its own natural accord…. It spreads internally so to speak and Miss Brown is a radiant performer.”95

Maxine Munt recognized in Trillium two themes, “a sit-down fall and handstands,”96 captured in one photograph showing her in an upside-down handstand with knees bent (see figure 1.1) and another showing her falling backward from a standing position (figure 1.7). Steve Paxton recalled, “It was odd to see a handstand in dance at that time. It was odd to see people off their feet doing anything but a very controlled fall,” and he remembered that Trillium also contained “a lot of very beautiful, indulgent movement.”97

Brown said, “Improvisation was not on the grid in New York. Bob Dunn thought it was not acceptable as an answer to a compositional assignment.”98 Paxton corroborated just how unusual and unique was Brown’s 1962 performance of live improvisation—also underscoring the fact that none of the deeply conceptual dimensions through which Brown brought Trillium to realization were recognized or understood. Paxton wrote, “I suppose that TRILLIUM was the first full-blown improvisation shown there, certainly a landmark for me. I recall that she performed it in an introverted fashion, yes shy, quick as lightning, short phrases, sudden shifts, at one point doing a quick, bent-legged hand stand, the body seen as animal and active outside the arena of ballet-derived dance on feet…. I feel TRILLIUM was a radical position in those times, expressing shyly and delicately an alternate to the idea of performance as directed outward so that the audience is essentially being choreographically lectured to, in the sense that the tone is raised and projected to present the material in a visually/kinetically comprehensible controlled form.”99

Figure 1.7 Trisha Brown, Trillium, 1962. Photograph © 1964 Al Giese

His notion of Brown’s dance as “being choreographically lectured to” and presenting improvisational material in a “visually/kinetically comprehensible controlled form” articulates precisely what Brown’s critics overlooked. Maxine Munt asked whether the Maidman Playhouse program offered “really studio studies,”100 not finished works—a statement similar to Schönberg’s about Trillium as mere “material,” not “dance.” Trillium cast movement outside of any recognizable framework, a technique comparable to Cage’s redefinition of silence and noise, in their materiality, as sounds to be heard apart from any a priori technique or method for creating or categorizing music.

Trillium announces an investigation into choreography’s different components: the distinction between a score and its performance, between choreography and improvisation, and between movement as a series of pre-set forms versus live movement discovered in the moment, through the execution of a score’s instructions. If all that remain of Brown’s dance are the three simple tasks on which it was based—as well as the artifact of its audio accompaniment—Trillium’s problematic reception at ADF introduces new information about the history of 1960s dance and Brown’s complicated attitude towards her participation in it.101

Yet Brown’s display of improvisational virtuosity in performing Trillium (1962)—according to her—was considered by her peers to be overly personal, which she interpreted to mean that displaying her abilities as a dancer did not fit with their stern principles. Writing in her notebook (some years later), she remembered, “In the early years of my career I was distinctly able to levitate. Peer pressure against virtuosity stopped me. Now I can’t do it.”102

Informed by her later discovery and embrace of her idiosyncratically original talents as a dancer, Brown repeated these sentiments in an interview that partly explains the lack of nostalgia which characterized her view of the Judson era: “The great irony of Judson was the good joke they pulled on me: I happened to be a virtuosic dancer, and they said ‘no’ to virtuosity. I had this body capable of moving in ways that not even I fully knew—except that I tasted the rapture of that experience when I was improvising.”103 This statement dates from the moment (in 1978) when—after a sixteen-year hiatus in which she focused on choreography and movement’s objective dimensions and functions—Brown revisited her early interest in improvisation as the foundation for a new movement language, sourced from within the unique subjectivity of her dancing body. Thus the Judson ethos (perhaps as consolidated in Yvonne Rainer’s 1965 “NO” manifesto) had its powerful effect on Brown’s direction and artistic choices.104 As she later recalled, “I got the picture from everyone around me to tighten up my act. I wanted to fit in with the group…. I created a more systematized frame-work in which to behave.”105