Читать книгу Our Great Canal Journeys: A Lifetime of Memories on Britain's Most Beautiful Waterways - Timothy West - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

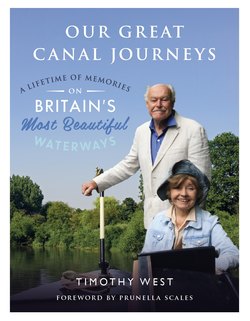

MR & MRS WEST

ОглавлениеIN THE MIDST OF THINGS, two young actors met in a gloomy church hall in Pimlico, in order to rehearse a romantic television drama about the eighteenth-century Earl of Sandwich. It was a terrible play, but it was work, and in those early years television plays of any sort were thin on the ground.

As I was playing only a small part, I knew there’d be a lot of waiting around, so I had brought along the Times crossword. Across the room I saw that the attractive, rather soberly dressed young woman playing the Bishop of Lichfield’s daughter had decided to do exactly the same thing. Her name was Prunella Scales. We began to sit together when we weren’t needed, and jointly attack the crossword.

Two weeks passed like this, and then it was the recording day. We all turned up at the BBC Lime Grove Studios, put on our wigs and costumes and waited to be called to the set. Time passed. We were told that, unfortunately, we had hit the middle of an electricians’ strike, and until this was settled there could of course be no possibility of recording the play. The negotiations went on until it was now clear that we’d run out of time, and the director called us together and told us that we could all go home. It had been found impractical to reschedule the programme, so we all made noises of mostly spurious disappointment and got out of costume. I turned to Pru and suggested we might go to the pictures.

So we got a bus to the Odeon Marble Arch and saw The Grass is Greener, starring Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr.

I don’t think we were aware of the aptitude of the title. I was just coming to the end of an unsuccessful seven-year marriage, and my wife Jacqueline and I had finally agreed that we’d be better off apart, and free to explore other possible relationships.

However, when the film was over, all that happened was that Pru and I said goodbye, swapped addresses, and hoped very much we’d work together sometime. Pru went back to the Chelsea flat she shared with three other girls, and I returned to our family house in Wimbledon.

Some weeks later I got a postcard from her, saying that the BBC had resurrected that awful play and that she had reluctantly agreed to be in it again. Pru said she was sorry to find I wasn’t there. I wrote back to explain that I was now engaged on something else. She said she missed me. I said I missed her too.

We began writing to each other fairly regularly. We’ve both always preferred the letter to the telephone, and, now that we were engaged in two different touring productions, we got into a rhythm of entertaining each other weekly with news about what the town was like, the theatre, the landlady.

Notepaper was expensive, and Pru took to using the backs of old radio scripts.

‘They’re very absorbent, aren’t they? Do you think what you save on paper you lose on ink?’ she wrote to me.

Chatty, jokey and inconsequential as these missives were, we were both accomplished enough letter-writers to be able to read between the lines. We were falling in love. So somehow we had to get to see each other; and finally, one week in the early summer, that became possible. Pru had gone straight into rehearsing a new play at the Oxford Playhouse, while I was on tour with the farce Simple Spymen, playing a week at the New Theatre round the corner.

Pru of course was rehearsing all day, and I was performing in the evening, so we didn’t meet properly until Sunday morning. The day dawned warm and cloudless; we wandered round the city, had a nice lunch and hired a punt at Folly Bridge. I handled the pole dutifully for the first half-hour, ice-cold water running up my arms and soaking my shirt, then I sat down and just let us drift into the bank.

I still remember that afternoon on the river. I recall clearly what we were both wearing, the colour of the cushions in the punt, the parade of ducklings striving to keep up with their mother, and our being stared at critically by two moorhens in the reeds.

Pru and I have always loved the water – being on it, beside it, and sometimes in it, although I’m a terrible swimmer. Yes, we owe a lot of our lives to the water.

Bird-life is happily ever-present when boating and, to this day, watching my children feed the ducks brings back happy memories.

After finishing the play at Oxford, Pru joined the cast of The Marriage Game, which again meant a prior-to-London tour, while I was still going round the country with Simple Spymen. We were desperate to get together whenever we could, and we contrived a series of Sunday assignations at cross-points in our touring schedules. If Pru had been playing in Birmingham, and was about to move on to Newcastle, and I had just left Liverpool and was going on to Hull, then we might meet in Sheffield. If she was travelling south from Leeds to Brighton, and I was going in a westerly direction from Norwich to Bristol, we could perhaps rendezvous in Coventry. We had a lot of energy in those days; and we learned an enormous amount about trains.

Pru and I had grown up in very different surroundings, which meant that there were always interesting and surprising things to learn about each other’s early life. Pru’s father had been a professional soldier, who had fought in both world wars. Her mother had been on the stage but had given it up on getting married. The family lived in Abinger in Surrey, where Pru was born. She went to a girls’ school in Eastbourne, which, when war broke out, was evacuated to the Lake District. After leaving school she enrolled at the Old Vic Theatre School in south London, where she was spotted by a rather good agent who put her up for a number of things. She auditioned successfully for a part in Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker, opened in it at the Theatre Royal Haymarket and then went with it to Broadway. From then on, her professional life (we both hate the word ‘career’) embraced theatre, television, film and radio, and continued pretty well without a break.

My parents were both ‘in the business’, though my mother gave it up when her second child, my sister, was born. My father was a popular and respected actor, but it was a long time before he reached the West End, and most of my young life was spent chasing him round the country. He had just secured a job in Bristol, when war broke out, and he had to enlist as a War Reserve policeman. We got a flat, and lived there for the duration. In 1946, we moved to London (well, the London area) and, after attending the John Lyon School and the Polytechnic in Regent Street, I took jobs first as an office-furniture salesman and then, because I love music, as a recording engineer for EMI. Eventually, I owned up that what I really wanted to do was to be an actor.

I took the long and rocky climb through various different repertory companies of uneven quality. At the beginning I was in places that did weekly rep: performing one play in the evening while rehearsing the next one during the day, for perhaps forty-six weeks a year, including the panto. Obviously, we can’t have done the plays very well, but we did them, and it delivered a form of training unavailable to young actors today. No drama school can possibly hope to provide that variety of text, style, manners, dialect, costume and behaviour that was needed if you wanted to keep your job in weekly rep.

So you could say I learned my trade by doing it, whereas Pru’s drama-school training was rather more innovative and academic. When we first knew each other I thought of myself as a useful, quite versatile actor who could play older parts more cheaply than the more senior actors who ought really to have been playing them. Pru got me to think more imaginatively about myself, and about the real process of acting. That was perhaps the first of many occasions in life when she has seen fit to offer a subtle push in the right direction. I sometimes don’t realise it till later.

Our lives have often followed wildly different directions, but we cherish the opportunities we’ve had to appear on stage together: When We Are Married, The Merchant of Venice, Love’s Labour’s Lost, What the Butler Saw, The Birthday Party and Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Sometimes we feel, though, that our joint appearance could actually prejudice the play: if the characters we’re playing are going through some romantic turmoil or insecurity, might the public say, ‘Oh, no, it’s all right really … they’re happily married’?

My tour lasted a full twenty-six weeks, but, when it finally came to an end, I decided to audition for what was known as the BBC Drama Rep – and was accepted. The Rep was a company of about forty actors, paid a weekly salary to perform in all aspects of BBC Radio – plays, stories, letters, poetry programmes, comedy shows and the odd bit of announcing. I have always loved working in radio – for one thing you can play parts for which you’re physically quite unsuited – and I passed a very happy, wonderfully varied year. I learned a great deal from my Rep colleagues, who included some of the great names of radio, and with them I enjoyed many riotous sessions in the BBC Club round the corner.

Pru and I celebrate an opening at the Grand Theatre, Blackpool, with inadvisable quantities of champagne.

The significant thing was that I was being paid regularly, by the week, and so I had begun to embark on the serious process of getting a divorce. I had feared this would prove a wearisome and ignominious business; but, as it turned out, not at all. I was being the guilty party, and Jacqueline’s solicitor had engaged an enquiry agent, who just wanted to know where and when he was supposed to discover me in flagrante delicto with ‘Miss X’.

My beautiful bride and I, newly wedded.

I was staying in a hotel in Cheltenham, where I was directing a play, so he would have to come up there. We suggested a suitable date, and Pru, as Miss X, came up from London to join me overnight. However, the agent didn’t relish an early-morning start, and the train he proposed to catch from Paddington would not deliver him to the hotel until after I’d had to leave for the theatre and Pru had gone back to London. What could we do?

There was no problem, the helpful chap explained: Miss X’s presence was not obligatory, nor, apparently, was mine. ‘Twin indentations on the pillow will suffice,’ he said, ‘though perhaps an item of lady’s night apparel might serve to clinch matters.’

I looked up a more acceptable train for him, we exchanged cordial wishes, and Pru went out to Marks & Spencer and bought a matter-clinching class of nightgown. The following morning I draped it over the bed, thumped the pillow twice, and went to rehearsal. In due course, the decree nisi came through.

One day, according to Pru, we were held up at some traffic lights on the A30, when I reached into my pocket and brought out the ring I’d bought in a rash moment in the Brighton Lanes, and asked, ‘Will you marry me?’ Obligingly, she said oh yes, all right, then the lights changed and we moved on.

We got married quietly at Chelsea Register Office on a Saturday morning in October. We both had to get back to work on Monday, but for the time being we had two nights of wedded bliss to spend at a riverside hotel in Marlow, which turned out to be possibly the most celebrated venue for illicit weekends in the Home Counties, with a waiter who gave me a conspiratorial wink and murmured, ‘I think the lady has already retired upstairs, sir.’

The following spring we found we had a week off, and so we went off to Llangollen in North Wales for a week, and decided that was our honeymoon. Our son Samuel was born in 1966 at the rather smart

Queen Charlotte’s Hospital, Hammersmith; by the time his brother Joseph came along, our gynaecologist had moved to King’s College Hospital in the slightly more downmarket area of Denmark Hill. Pru remembers the marked contrast in the way the births of the two boys were registered:

Following Sam’s birth, a very elegant man in striped trousers and a dark jacket knocked softly and came in. ‘Good morning, Mrs, er …’ – he looked at his list – ‘West. Many congratulations on the birth of your, um, son. When you and your husband have decided on a name, would you mind coming down to the office and registering him? Thank you.’

After Joe’s birth in SE5, a typed slip was sent to me at home, telling me, ‘Please register your child without fail by such-and-such a date.’ So I went off, between feeds, to the Nissen hut beside the hospital, into an office full of tables, where I stood in a queue. I sat down at the next available table, and the registrar asked, ‘When was baby born?’

‘New Year’s Day,’ I said proudly.

‘Oh, yes,’ she said. ‘That would be January the …?’

‘First.’

‘Are you married to baby’s father?’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘What are you going to call baby?’

‘Joseph John Lancaster.’

‘And it’s a little …?’

‘Boy.’

(Both these encounters were on the NHS, just a different postcode.)

Joe’s arrival meant that we no longer fitted into our little terraced house in Barnes, and needed to move somewhere altogether bigger.

I’d just done two years with the Royal Shakespeare Company, but, as they didn’t hold any plans for me in the future, I was now on the lookout for something else. Pru knew the director Toby Robertson, who ran the Prospect Theatre Company, and we went round to see him at his house in Wandsworth.

A gaggle of cherubic children are all very well and good, but they are famously inconsiderate when it comes to taking up real estate in the house.

I ended up working with him for seventeen years, on and off, but in the meantime we’d seen a house just round the corner from him that we rather liked, so we took out a mortgage and bought it.

We’ve been living there now for forty-five years, very happily: it’s well served by buses, and but a short walk to wonderful Clapham Junction, perhaps the most useful railway station in Europe. I don’t like driving in London, as I can never find anywhere to park; and so Pru and I use public transport all the time. For one thing, now we have our sublime Freedom Passes, we can travel without cost on buses, the Underground and far beyond the suburbs by National Rail. Sometimes, if one of us has recently hit the screens, people say they’re surprised to see us on the Tube. ‘I thought you people went around in limousines?’ they ask, in tones of disappointment. Well, I suppose some do; but we think it’s part of our job as actors to study the people we see in daily life, to try to imagine what they do, how they live, what gets them out of bed. You can’t do that sitting in the back of a taxi.