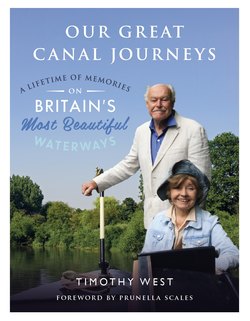

Читать книгу Our Great Canal Journeys: A Lifetime of Memories on Britain's Most Beautiful Waterways - Timothy West - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTOUR DE FARCE

OVERSEAS TOURING, particularly of classical drama, meant that we were working abroad quite a lot. We wanted the boys to be with us as much as possible, so the current au pair/nanny/mother’s help did get to go on some quite nice holidays: in Australia, the United States, Europe and the Middle East.

There’s one particular tour I remember: through Yugoslavia (as it still was then), Turkey, Jordan, and Egypt. I was acting as staff director for our three productions: Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra and War Music, a verse/music/dance staging of Christopher Logue’s translation of the Iliad; and it was my job, as well as playing Claudius, Enobarbus and the Storyteller in War Music, to fit all three shows into the various venues that we’d been allotted.

We opened in Istanbul, in the open courtyard of Rumelihisarı Castle on the shore of the moonlit Bosporus, which served very excitingly for War Music; but the next night’s performance was Hamlet, and somehow we hadn’t taken into account the presence of a nearby mosque, from which the Muezzin’s loud appeal to prayer came just as our Marcellus observed that something was rotten in the state of Denmark.

The views along the Bosphorus where we staged our production of Hamlet, are spectacular. © Getty

Although afterwards the tour was accounted very successful by audiences in all the places we visited, we did seem to be dogged by various kinds of misfortune. Our next date was Ljubljana, in Slovenia; and when we arrived we found that a number of our wardrobe skips had been lost in transit. Maybe our swords and shields had been impounded for safety by customs officers who were gaily trying on our wigs and frocks. They eventually did arrive, but too late, and that night the forces of Rome and Egypt had to go to war unwigged and unarmed.

Dubrovnik was next, and for Antony a special arena had been built in the square in front of the Ducal Palace. We could not begin the performance until after dark, when all the cafés had closed and all the starlings that inhabited the square had gone to bed for the night. And then the stage lights came on, and a thousand birds awoke to greet the supposed dawn, lustily drowning out every word that was spoken on stage (classical actors didn’t use microphones in those days!). Not many people stayed after the interval.

We moved on up the coast to the Roman port of Split, and here we performed on the forecourt of the splendid Palace of Diocletian. It looked wonderful; the only worry was that, if an actor had to make an exit on one side of the stage, and re-enter shortly afterwards on the other, he or she had to go down some steps to a courtyard and along a narrow public alleyway into a side street, and thence back into the palace by a side entrance. Sometimes this had to be done fairly rapidly.

One night, one of Cleopatra’s court, wearing a very bulky robe, had got as far as the alleyway when he found his path blocked by a very fat local citizen coming in the opposite direction. ‘Back up! Back up!’ shouted our actor, but the man, muttering his rights, stood his ground. Finally the resourceful actor drew his sword and brandished it above his head, and at that his opponent turned and ran, screaming.

Pru and the boys came out to join me in Jordan, where we were to play in the Palace of Culture in Amman (actually a 6,000-seat basketball stadium). The stage lighting was completely inadequate; I complained, and was promised that extra lamps would be delivered and installed in good time. They weren’t. I had not then learned that in some Arab countries it is considered discourteous to refuse a request: they say yes, and then don’t do it. I was prepared that this State Performance of Hamlet, in front of King Hussein and a possible audience of 6,000, would have to happen more or less in the dark. In the event, only about 350 people turned up, and we seated them together in a block and directed what lights there were onto what they could see.

The security arrangements for the royal visit were exhaustive. Our set, together with the furniture and properties, was closely examined; even the Leichner sticks of makeup still used by some of the older actors were probed by sharp knives in case they disguised cartridges. During the performance, a dozen heavily armed soldiers were stationed backstage, one of whom was discovered when Hamlet draws back the arras in the bedroom scene, gazing down in concern at the dead Polonius.

We were in Amman for quite a few days, and, while we were there, the company fell prey to various gastric disorders – though mercifully our own family were spared. At one point eight actors and two musicians had been committed to hospital, a couple of whom dragged themselves out each night for the performance and quickly returned to their hospital beds afterwards. Everybody had to cover for somebody else, we combined parts, cut whole scenes, and just about managed to make sense of the plot.

No matter how ridiculous and cumbersome the costume, no matter how un-ideal the location – no matter how temperamental the horse – the show must go on.

© Rex Features/ITV

The Theatre of the Sphinx in Cairo, our final port of call, has a long stage raised four feet above the desert sand, and at each end of the stage is a short flight of steps, in the dark, down to the dressing-tents. On our closing night someone had moved these steps; I didn’t know, and fell four feet. Not a long fall, but unexpected, and I tore my Achilles tendon. (Later, it broke completely, which caused me a lot of bother and I had to have an operation to fix it.)

That was the end of an eventful tour, but the company remained in fine spirits; and those of us who were sufficiently recovered from our ills to hire a pony first thing in the morning and ride down the long valley to Petra – ‘a rose-red city, half as old as time’, as John William Burgon put it in his magnificent poem, also called Petra – and see the incredible Roman Treasury carved into the rock, enjoyed an experience that made up for all the trials and tribulations we’d encountered during our wanderings.

While I love travel, Pru maintains she doesn’t really like opening the front door to put the milk bottles out. It’s not true: she loves it really. I think.

The boys like it, anyway; at least Joe did: ‘For one half-term, Ma took us to Paris, Strasbourg and Luxembourg and we stayed in cheap, dusty, elegant European hotels. I really liked seeing different places. We went to Jordan, Egypt and the US, and to Australia twice, which I loved.’

Pru and I have worked in Australia on numerous occasions, and at one time we even thought of going back to live there. But then we wondered whether we would still be welcome: Australian acting was now doing very well, thank you, without any assistance from the Poms!

Our favourite place in Australia was Perth, technically the most isolated city on the globe, 2,300 miles away from its nearest neighbour, Adelaide, across the desert of the Nullarbor Plain.

Because of its distance from anywhere, it has a vibrant social life of its own, and an appetite for travel that is external rather than internal. Someone will tell you they’ve made their annual pilgrimage to Bayreuth, Salzburg and the Edinburgh Festival; but poor Auntie Alice in Sydney has had to go unvisited.

We appeared a number of times at the Perth Festival, counted among the best literary and musical events in the world. Pru directed Uncle Vanya for the Western Australian Theatre Company, with me as Vanya (I like being directed by Pru, she’s very good). I did a term with the University of WA, as Director-in-Residence, and did a student production of Middleton’s Women Beware Women.

This photograph was actually taken in Melbourne. You can see from Pru’s outfit that, perhaps, we had been spending a little too much time in Australia…

The only trouble with Perth is that its amazing lifestyle can prohibit you from working. The city is built round a beautiful harbour, too shallow to permit commercial craft, so nearly everybody has a little boat of some kind, in which, armed with a pack of Foster’s, they can sail, row or motor down the River Swan to Fremantle for a seafood lunch.

Pru’s remark about her reluctance to put out the milk bottles is, I’m afraid, utter rubbish. For twenty-five years – yes, twenty-five – she has been doing single performances of An Evening with Queen Victoria, a programme compiled from the Queen’s own diaries, and performed with the tenor Ian Partridge and the pianist Richard Burnett. She plays Victoria from the age of sixteen until her death, without any change of makeup, and the effect is remarkable. The three of them have taken the show all over the world, and I can’t think how many air miles they must have clocked up. So forget the milk bottles.