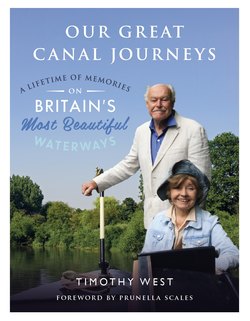

Читать книгу Our Great Canal Journeys: A Lifetime of Memories on Britain's Most Beautiful Waterways - Timothy West - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNARROWBOAT NOVICES

ALL THIS MAY SEEM a long way from the world of canals. However, in 1976, our friend Lynn Farleigh rang and offered to lend us her narrowboat for a fortnight. I’d rather forgotten about our domestic waterways, and for Pru it was quite a new subject. She knew about the Suez Canal, and the Panama Canal, and, yes, all right, the Manchester Ship Canal, but the idea of going from Oxford to Banbury by water seemed to her pretty remarkable.

In fact it turned out to be perhaps the best holiday of our lives. The summer of that year remains famous for its uninterrupted warm sun and cloudless skies; the swans, ducks, moorhens and water-voles, the herons and kingfishers were enjoying life to the full as the canal wound its sinuous way through the bewitching Oxfordshire countryside. The boys, then twelve and ten, got so blissfully exhausted operating the locks and lift bridges that by six o’clock they were flat on the their bunks, and Pru and I could open a bottle of wine and sit watching the setting sun and hearing the gentle trickle of water from a remote lock gate.

A cunning ploy to get children into bed early is to recruit them into intensive manual labour. Never fails.

For us it was the start of a lifetime’s fascination. I don’t know how a pair of busy actors found the time, but somehow we determined to explore as much as we could of the whole canal network. This took us years, of course. We had to fit it in between jobs: picking the boat up from wherever we’d left it, and then abandoning it somewhere else, perhaps knocking at a nearby cottage and leaving our phone number just in case there was a problem.

Lynn eventually sold us her boat, which went on to serve us for several happy years until we got tired of having to dismantle the dining table every night to turn it into a double bed. We would delay this irritable task for so long that often we would wake up at three in the morning, our heads on the table, shivering with cold. So, instead, we commissioned our own, longer, narrowboat, bought the hull, designed it and had it fitted out at Tooley’s famous boatyard by the marine engineer Barrie Morse. The launch took place at Banbury in the winter of 1988: we christened her after our brilliant female accountant who had managed somehow to allow the purchase against tax (‘Extra Office Space’).

We had no idea, at the time, how many happy memories from our lives would come to pass on our precious boat.

Incidentally, by giving our boat a feminine identity we are actually flying in the face of canal tradition. To the working boatmen of old, their craft might proudly display an elegant female name, but was still firmly referred to as ‘it’. Similarly, ‘port and starboard’ were frowned on: they preferred left and right; also a boat had a front, and a back. I’m afraid Pru and I have found it impossible to adjust; I suppose secretly we like to pretend we’re accomplished global seafarers.

We kept, and still keep, a logbook of all voyages. Somehow the actual launch didn’t get logged (too much champagne, perhaps) but here is the entry for the boat’s first family trip (my father, aunt Joyce with her new dog Sally, Pru and myself), from Banbury up to Cropredy and back:

Sunday 18th December 1988: Everyone very impressed with the new boat, the cooking stove and to a slightly lesser extent, the loo. T still discovering that a 60’ narrowboat is at least 12’ harder to navigate than a 48 foot one. Going round sharp bends you will have your rudder aground if you’re not careful. Well, there’s not much water in the Oxford Canal just now. Chief delight is how warm the boat gets, and how quickly. It was well nightfall by the time we got back to Tooley’s, and found there was no mooring available: while we were away, Barrie’s new client had crept into our spot. We moored alongside, but it was clear that our senior passengers couldn’t manage the plank, so we moved up to one of the staithes [landing stages] and put them ashore. It was then that the stern line got wound round the prop shaft, and I spent the best part of an hour on my face, with an arm in dark freezing water to unravel it. Never mind – I’m pleased to learn it can be done.

On our earlier boat we had already covered a great deal of the national waterway system. We’d sailed up as far as Ripon in North Yorkshire, the furthest in point in England to be reached by canal; we had explored the intricate water-webs of Birmingham and the Black Country, and taken the Grand Union (by far the prettiest way to view Milton Keynes, if you have to) all the way back to London.

One important route, though, was closed to us as yet. Since the afternoon I saw that farmer fall into the mud, the Kennet and Avon had undergone a spectacular reversal of fortune. A petition with 20,000 signatures had been addressed to the Queen, and it led to a phenomenal restoration programme carried out by volunteers who included servicemen, prisoners, students, schoolchildren and Boy Scouts. The entire eighty-seven-mile length across the country from Reading on the Thames to the River Avon at Bath, and thence to Bristol, was reopened in 1990; and it occurred to the television company HTV West that it might be nice to arrange for Pru and me, who were quite well known to the area, to be recorded on film as the very first boaters to travel the reclaimed waterway.

We got two friends to accompany us on the journey, and set out on our adventure, beginning at the start of the actual canal in Bath, just below Pulteney Bridge. Nervous but enthusiastic members of the K&A Trust gave us a send-off and followed our progress at a discreet distance, while a considerable crowd turned out to watch us negotiate the momentous sixteen-lock staircase at Caen Hill.

At one point we had to break our journey for a few days while the stretch of canal ahead of us had yet to be supplied with water; but, apart from that, the only interruption to our maiden voyage was a readjustment to allow the Queen to perform the official reopening ceremony in a week or two’s time. Her Majesty’s ceremonial barge had to be the first to pass down through the top lock at Devizes, on its way to the spot where the reception was to take place. A journey of only a few hundred yards all told, but necessitating our sixteen-ton narrowboat to be craned out of the water, loaded onto a flatbed truck and driven round the streets of Devizes before being winched back into the canal a few yards further on. So, when we boast of having sailed the whole eighty-seven miles of the canal, it would be more accurate to say eighty-six and three-quarters.

Our boat’s stately procession, via a flatbed truck, several hundred yards down the canal past the top lock, so that Her Majesty could be the first to sail through the new lock gate. One suspects she probably wouldn’t have minded us going first.

Once we’d watched the perturbing spectacle of our boat being dropped back into the water, we were able to attend the royal ceremony, and talked briefly to Her Majesty, who seemed pleased with the event and remarked on the distinctive variety of butterflies that she’d witnessed on her short trip.

HTV’s four thirty-minute episodes were much enjoyed when they were shown locally, and I think may well have drummed up tourist interest for the canal, which at that time it rather needed. Now, of course, with its beautiful scenery, remarkable features of engineering and pleasant, welcoming towns and villages, it’s top of the location list for many canal enthusiasts. It certainly found a place in our own lives: for years we kept our boat at Newbury, performed shows at the little theatre on Devizes Wharf, ‘adopted’ a lock at Combe, and became Patrons of the K&A Trust.

Wonderful though such memories of canal life are, being actors also meant travel of a different nature, as we’ll see.