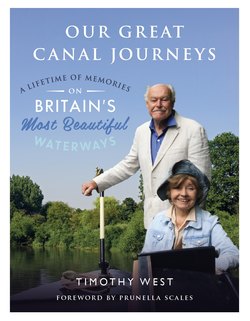

Читать книгу Our Great Canal Journeys: A Lifetime of Memories on Britain's Most Beautiful Waterways - Timothy West - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE BIRTH OF GREAT CANAL JOURNEYS

ОглавлениеIT’S AUTUMN, getting cold, and it’s time our boat went into dry dock to get its bottom blacked. If you own a canal boat, and you’re not intending actually to live on it full-time, of course it’s essential to find a winter home for it where it will be safe, accessible and looked after. For years we found such a place at a boatyard in Newbury owned by Bill Fisher and his wife, who were pillars of the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust.

I can’t remember why, after many years, we decided to relocate: I think perhaps we just wanted some new scenery. Anyway, we found a mooring at Banbury, not far from where our boat was actually built. The mooring was directly on the canal, but to reach it by land you had to go through a locked gate (we frequently mislaid the key and had to ring the owners at home at all hours: they didn’t live on the premises). It was only when they decided to retire and sell the mooring that we thought maybe the time had come to move on.

Various canal obligations had brought me into contact with a man called Tim Coghlan. Tim is king of the canal network’s boatyard proprietors and held sway at his vast marina at Braunston, Northants. Situated as Braunston is, at the hub of commercial canal traffic, stretching north to Coventry, northeast to Leicester, southeast to London, southwest to Oxford and due west to Birmingham, it has always been a national centre for mooring, boatbuilding and repairing, and a gathering of the canal community. Here we made our resting-place.

People who are unused to canal boating come to us sometimes for advice. How can you can ever be comfortable in the confined space of a narrowboat? they ask. Is there any discipline that one has to learn, to be able to cope with dimensions of (in our case) 60 foot by 6 foot 9 inches?

Well, yes, you have to learn to be quite tidy; but in a well-designed boat there should be plenty of storage space for books, crockery, kitchen utensils, glasses, bottles, tools, bedding and cleaning materials – just don’t leave things about.

As for human beings: our boat can actually accommodate six – two in a double bed and four in individual bunks – but people have to know each other pretty well, and not snore.

If you’re just hiring a boat for a week or two, resist the temptation to bring loads of exotic groceries, toys, CDs and board games: just take what you need to arm you against possible continuous rain (it can happen). You need your energy, so eat up. Pru enjoys cooking on the boat (actually rather more than she does at home). Take advantage of the various canalside hostelries that offer good food, local real ale and usually entertaining company.

You shouldn’t set too much store by getting to a particular place by a particular time. As one of the ladies we met while filming in Scotland put it, ‘If you want to make God smile, tell him your plans.’ There will always be a church you’d like to peer into, a hill you would like to climb, a wood you would like to explore; and you just feel you haven’t the time.

The Nicholson waterways guides are essential. There are seven of them, for different areas of the country. They describe the terrain in front of you, map out your route, give you distances, show aqueducts, cuttings and tunnels and identify the locks, bridges, moorings, boatyards, water and sewage points, and pubs. They show you the off-canal availability of shops, post offices (sadly, not many), bus stops and railway stations.

Moorings, these days, can be difficult to find. On some of the most popular canals you can go past perhaps a mile of tethered craft before you can find a space. If you’re leaving your boat to go ashore, lock up firmly. It is rare to be burgled; though our boat was once broken into, for, curiously, a packet of muesli and some corduroy trousers. It turned out that the perpetrator was in fact known locally: he made a practice of stealing from moored boats during the summer months, but, as the weather grew more unkind he would arrange to be apprehended, and spend the winter as a guest of Her Majesty. Then he’d come out and start all over again.

Rocketing housing costs, particularly in London, mean that people are flocking to live in narrowboats and one can see the resulting congestion for oneself, as here on Regent’s Canal.

© Getty

More and more people, especially in cities, are buying a second-hand narrowboat to live on, at perhaps a tenth of the price they’d be asked to pay for a one-room flat. But that’s only the start of it: there’s a licence and insurance; and mooring fees can sometimes be really expensive in a marina or secure boatyard. If you can find a space along the towpath to moor up, that’s all right for a fortnight, and then you’ll have to move on somewhere else; that’s the law.

Do we live on our boat for any length of time? we’re asked. Yes, often, when there is a canal with a secure mooring near the theatre at which we’re playing. It’s a home. We’ve lived aboard in Bristol, in Bath many times, and in Leeds for a while. Sam borrowed the boat for two seasons in Stratford-on-Avon.

Pru regards the boat as a second home; the only thing she really misses is the garden. Pru is a very keen gardener. We have a lovely garden at home, and when she’s away she likes me to attend to it, and report on progress. I’m a novice. This is a letter I wrote to her in 1968:

The Garden. Ah, well now. Umm. Yes. Yes. Right you are. Well, here goes then. RIGHT. From the beginning. First things first. My general impression is that there are more leaves than flowers. Just so. Quite a lot more, in fact. The next thing that strikes the intelligent observer is that what flowers there are, are to be found on the left, as you look out of the window. None on the right. No. What are these flowers, you will wish to ask? Well, they are mostly those pink ones, you know, several to a stem, also available in blue. And white too. Oh, and purple. Or are those different? Anyway, there are about ten in all.

Now I don’t want to stick my neck out here, but I believe I may be right in saying there are some daffodils on the same side of the garden, and one thing I’m pretty sure of is that there were a lot more of them at this time last year. At the end of the garden we seem to have a lot of tall green stuff with small yellow bits on top. A considerable amount. Probably more than anyone else in the road.

Well, that’s about it. Yes, I believe that just about wraps it up. Anything else you want to know about the garden, you know you have only to ask.

Some people like to create gardens on the tops of their boats. If you’re living aboard permanently and not moving, that’s fine, but, if I had to steer while trying to peer between hollyhocks and sunflowers, I think I might bang into things. (I do bang into things sometimes, and not always by accident: Channel 4 rather like me to have a bump from time to time.)

An early precursor to Great Canal Journeys.

We were beginning to be recognised on the canal circuit, and I was approached by Carlton Television in Birmingham to introduce a series of weekly half-hour programmes about canals and their history, entitled Waterworld, dealing mainly, but not solely, with the West Midlands. It was put together, produced and directed by the admirable Keith Wootton, and there was some splendid footage and lovely archive photography. All I had to do was a short piece to camera to introduce each episode. We did it for nine years, and it was very popular in the Midlands. We were preparing for a tenth year when Carlton told us that, due to cuts, locally shown programmes had become uneconomical. So why not show them nationally, on the network? we asked. Ah, no, they explained; you see, there are lots of areas in the UK that just don’t have canals. We said, well there are lots of areas in the UK that don’t have volcanoes, or glaciers, or rainforests, but they make pretty good television. But, no, they wouldn’t budge.

I don’t exactly know how Great Canal Journeys came about. Perhaps someone at Channel 4 had seen Waterworld and thought it was a good topic that could be expanded. Or did the idea come fresh from the independent company Spun Gold Television, and did they pitch it to the Channel? I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter. Spun Gold are a pleasure to work for, and C4 are immensely supportive.

The unit that we work with is very small: there is Mike Taylor, who is in overall charge, functioning as producer, director and screenwriter; James Clarke was our senior cameraman on all the early episodes, with Gary Parkhurst on second camera; Sam Matthewson did the sound, and we had different production assistants and a different runner for each shoot. As time went on, the wonderful Catriona (‘Trina’) Lear joined us as PA, researcher, caterer, wardrobe mistress and line producer, and Pru and I made up the small, happy and efficient family. In the last couple of years we were joined by my darling daughter Juliet, who, after her mother and I parted, came to live with Pru and me, and eventually occupied our basement flat. Juliet is a professional hairdresser, and, as our unit wasn’t grand enough to boast a dresser or a makeup artist, Pru fell on her neck sobbing with gratitude.

Whilst Pru and I are front and centre of the show, none of it would be possible without our fabulous – and very patient – crew.

Making a programme that is meant to look spontaneous and impromptu does of course take quite a lot of planning. Preproduction work starts with selecting a location, somewhere that we, and we hope the audience, will be excited by. What will the weather be like? Might there be any political problems leading to restricted access? Where exactly should we go? What should we see? Whom might we talk to about the history of the place, and of the canal or river? What is there of literary, artistic or musical interest? And so on. Also, we have to charter a boat.

When we feel we have enough potential ingredients to make a good programme, a route has to be planned that if possible can include it all within a six- or seven-day shoot. Mike, with Trina and the leading cameraman, will first of all go out there on reconnaissance to plan how to make it all possible and think how to capture it scenically.

Meanwhile, Pru and I will do a bit of reading: is there a local writer, a poet or dramatist that we should be able to quote; any local legends we should know about? Latterly, we have had the services of a researcher to do a lot of the groundwork, and they have often come up with some quite surprising things.

Something we had to decide upon, before we started making the series, was how open we should be about a condition in darling Pru that had been diagnosed as vascular dementia. In appearance, this is very similar to Alzheimer’s disease, but develops more slowly (at least it has in her case).

It must have been at least twenty years ago that I came to see Pru in a play she was doing at Greenwich, and I thought, There’s something wrong here. It wasn’t that she was uncertain about her lines – she obviously knew them perfectly well – but there was just this sensation that she had to think for a millisecond before she spoke.

Now that’s not how Pru works: throw her the ball, and she’s caught it and thrown it back to you in a trice. So after the show I just asked her if she was feeling OK, and she said yes, perfectly, thank you, what do you mean? I can’t remember how I persuaded her to go and see a specialist, who sent her for a brain scan, and they made the diagnosis.

Now, as I say, the progress of the condition was very slow, and still is, but before long it was beginning to be apparent to friends and to employers: things like repeating a story three or four times in half an hour, forgetting some vital thing she had been told, and asking the question again (Judi Dench, in her brilliant performance as Iris Murdoch in Iris, portrayed it exactly).

I had to think: is this going to be apparent when we’re filming; or, even if it isn’t, how many people will have heard rumours and be watching out for indications? So I decided I couldn’t possibly pretend to ignore it: to do so would be foolish, dishonest and altogether wrong. With Pru’s agreement and that of our TV producers, I made a clear statement about it on screen, and revised this as we went along.

How is it for me? Well, painful of course when I remember the wonderful girl I fell in love with, so clever, so funny, so adventurous. But one mustn’t do that, mustn’t dig into the past. Live for the present, just take it day by day. Day by day I don’t notice that much difference in her: physically she’s in amazing shape for her age, and still likes going to the theatre, to concerts, restaurants and so on, and especially being on the boat. She’s well aware of the problem, doesn’t like talking about it, and is not letting it get her down. We really do have a lot to be thankful for.