Читать книгу Peggy Lee - Tish Oney - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Capitol Idea

ОглавлениеPeggy Lee’s career as a major-label recording artist began and ended at Capitol Records, spanning twenty-nine years. She spent five of those years sharpening her jazz chops in the studios of a major competitor that became well known for its outstanding jazz talent. Overall, though, Lee’s home was with the Capitol family throughout the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s, and into the ’70s. She began winning the hearts of her fans even from her earliest days.

Toward the end of her tenure with the Benny Goodman Orchestra, on December 30, 1942, Peggy returned the Paramount Theater in New York for a special performance. This engagement happened to include the solo debut of a young singer who had recently left the Tommy Dorsey Band to actively pursue a solo career. Bob Weitman, the manager at the Paramount, booked this performer as an additional act on the bill. When Goodman dryly announced the entrance of this young singer, Frank Sinatra, the theater erupted in girlish hysteria akin to that accompanying Beatles concerts a couple of decades later. Both Lee and Sinatra would soon enjoy worldwide renown and stardom as fellow artists on the roster of a new label called Capitol Records. While the Paramount introduction may have left an indelible first impression upon both artists, their common link to Capitol would not commence for several more months.

In February 1943 the Goodman band spent six weeks performing in Hollywood. While there, Lee gave Goodman her notice of intention to leave the band, as she and Dave Barbour (who had already been fired for fraternizing with the singer) planned to marry. Another take on the story was that Dave had simply quit and asked Lee to marry him at the moment he informed her of his leaving.[1] Either way, the Barbours tied the knot in March of that year, and their daughter Nicki would arrive in November. In the meantime, Peggy found contentment in her domestic roles of wife and soon-to-be mother.

Producers at Capitol Records became interested in signing young Peggy Lee following the success of her hits with the Goodman band, especially “Why Don’t You Do Right?” which led to a video spot for Lee and Goodman in the film Stage Door Canteen. The film spot consisted of a scene containing a full performance of the song with the camera on the band and singer. The film’s popularity created some of the first inroads for Lee’s talent to be seen and appreciated on a national level. Just prior to the film’s release, the song itself rose slowly and spent almost five months on Billboard’s Top 30 chart in 1943, creating an unusually long period for the hit and its singer to bask in the public’s consciousness.

Lee’s subsequent successful recording dates as a guest vocalist with ad hoc bands also created allure strong enough to attract Capitol’s producers. Concert dates and radio performance opportunities continued to roll in. Lee, however, was committed to her new job as wife and mother and harbored no plans to return to her former mode of employment. She engaged her musical interests by writing songs with her husband. Dave eventually convinced Peggy to return to her career, feeling strongly that with such talent she would one day regret leaving the stage for a purely domestic life. Her husband was sensitive to the fact that Lee’s recent difficult childbirth and an ensuing hysterectomy would prevent her from ever having more children. Dave’s unflagging encouragement toward his wife to pursue a music career under such sober realities at home showed a support of his spouse’s best interests that was well before its time. As a result of Dave’s support, as well as the reality that the Barbours needed the money, Lee began accepting some performance and recording offers while turning others down as she sought balance between her home life and occasional work. This part-time music lifestyle proved to be short lived. As her daughter grew stronger, Peggy began to accept more and more offers to perform and record, effectively taking her career to the next level. Before Nicki reached her second birthday, Lee had fully returned to a life of music.

Peggy signed with Capitol Records toward the end of 1944 to begin an immensely successful solo career. Holding an active recording contract with Capitol for an impressive twenty-three years, Peggy Lee remained the longest-signed female artist that ever worked with this label. At the time her contractual arrangements began, she also signed with General Artists, a professional booking agency. Capitol Records indulged the Barbours to some extent, allowing many of their co-written songs to be recorded along with the other songs Peggy was given by the session producer. Some of the better-known Barbour-Lee collaborations included “I Don’t Know Enough about You,” “It’s a Good Day,” and “What More Can a Woman Do?” Each of these songs would eventually be recorded by Peggy with Dave Barbour and His Orchestra.

In November 1943 and January 1944 Capitol put together an ensemble called The Capitol Jazzmen to celebrate the end of the musicians’ union recording ban. Peggy Lee was called to participate in the second session. She initially declined but then accepted after receiving a second invitation. One song selected for this session was “That Old Feeling,” an Academy Award–nominated Sammy Fain and Lew Brown song from the film Vogues of 1938. In Lee’s version the song was accompanied by celesta, saxophone, bass, and drum set. This enchanting song suitably reintroduced Peggy to her talent for recording. Two months after enduring a cesarean section to deliver her only child, Lee infused a delicate passion and expressive technique into her tone as she wove the aural tapestry of this classic song. Lee’s tenderness matched that of saxophonist Eddie Miller as they gently related the story of a long-ago love reawakening. Lee’s heartfelt rendition of this jazz standard took its rightful place as an important early recording of it, long before Chet Baker contributed an up-tempo swing version to delight the ears and hearts of jazz aficionados a decade later, followed by Frank Sinatra, for whom it scored a hit in 1960.

In “Sugar,” another standard Lee recorded at that first Capitol recording session, Lee’s darker, huskier vocal quality came through in her heavily swinging interpretation. Her slightly naughty sound (produced simply by singing in a spoken pitch range, or alto range, with a wide expressive and stylistic compass) replete with slides, smears, and note bending yielded many sexist comments about her singing from the men who recorded with her. This disrespectful reception by men of Lee’s singular, bold style that sounded incredibly sexy while being marked with appropriate jazz sensibility constituted a challenge with which she would have to cope throughout her life. The male-dominated music industry unjustly judged female singers as sounding like tramps and whores if they sang low with a husky, emotionally charged tone. Likewise, the industry judged female singers to be pure, angelic canaries if they sang in a soprano register with a slightly more classical approach. This prejudice was expressed in comments made by the producer, Dave Dexter Jr., at the recording session during which these two recordings were created: “Peggy Lee could sing like a little girl in a church choir or a husky-voiced, tired old whore.” By contrast, Dexter considered Lee’s sweet and innocent rendition of “That Old Feeling,” which required her to sing in a higher register, “pure angel food.”[2] Music columnist and DJ Eddie Gallaher published: “Peggy is not the girl you’d run into at a high school prom. Her voice is more that of the girl in the smoke-filled room at a truckline café or at a juke joint along a Texas highway.”[3] On another occasion a band member stated, “This chick sounds like a drunken old whore with the hots.”[4] As tempting as it might be for some to consider such descriptions of Lee’s wide range of expression to be complimentary, one must remember that male singers (basses or tenors) would never have been given equally disrespectful judgments based on their expressive additions of smears, slides, changes in tone quality or range, or jazz ornaments. Being among the first Caucasian women to sing in the soulful, down-to-earth manner of her black blues and jazz contemporaries, Lee was exposed to criticism, sexism, attempted physical assault on her person, and other injustices purely on the basis of her talents and how she chose to use them. Enduring gender prejudice and assumed to be an easy sexual target based on her huskier singing style and alluring stage presence, Lee was chased backstage at the Paramount Theater by a group of male audience members. In response to Sinatra’s debut at the same performance, female patrons screamed and swooned. He was viewed as an untouchable idol, she as an objectified target to be played with and possessed. Lee quickly learned by this dichotomous injustice that she needed to protect herself from her audience and began to withdraw to a safer internal space. The safety Lee enjoyed in the recording studio became a creative haven she would return to for the rest of her life.

New American Jazz was the title of the four-disc album that was released from the first two recording sessions (November 1943 and January 1944) by The Capitol Jazzmen. The producer’s note in the album stated that no arrangements were used for the sessions. Instrumentalists and vocalists simply came and played or sang as they wished in an extemporaneous fashion. As jazz required improvisation, this absence of written charts ensured that the final product was, indeed, new American jazz. The album was only the third album ever released by Capitol, preceded only by Songs by Johnny Mercer and Christmas Carols (featuring St. Luke’s Choristers). In addition to Peggy Lee, vocalist and trombonist Jack Teagarden contributed vocals to songs on the New American Jazz album, although the two were not in the studio simultaneously for this session.

“Ain’t Goin’ No Place,” a heavy twelve-bar blues song also sung by Lee at her first Capitol session, was essentially spoken on pitch in the traditional manner of blues singing. Shining through in a few places, her upward-inflected speech style clearly betrayed a nod to the inflection style of Billie Holiday. One also heard the influence of the Empress of the Blues, Bessie Smith, in the strong, assured, full-voiced approach Lee used to sing this female-empowered text. Blues songs often possessed a repeated first line with a contrasting text in the third line that drove home the point raised in the first phrase. This twelve-measure form sometimes included, as in this example, a stop chorus after the first or second chorus, during which the accompaniment suddenly stopped. Musical rests (when the instrumentalists did not play) were then used to call attention to important words in the text. Immediately following the “stop” section an instrumental interlude led up to the final stanzas or verses. Lee finished this tune with a spoken question often attributed to her style. Collaborative composer John Chiodini asserted that Peggy was, in some ways, “the first rap artist,” frequently choosing to speak during a song for a particular desired effect.[5] In this case she likely improvised her final spoken thought: “Why don’t you come on home, baby?”

“Someday Sweetheart” was also recorded at Lee’s inaugural Capitol session with The Capitol Jazzmen, featuring a clarinet solo by Barney Bigard. This song matched the swing style she had first explored with her previous band, the Benny Goodman Orchestra. This piece required a lighter, sweeter-sounding approach than the blues song previously described.

The musical and stylistic distinctions Peggy routinely made in the recording studio deserve mention. The three styles exhibited at this single recording session over four songs—blues, swing, and romantic ballad—each received a singularly authentic rendition and approach. While most singers would have sung all four selections with the same vocal color, breath support, technique, diction, and overall sensibility, Peggy Lee by this time in her career began to consider a song’s background, theme, rhythmic feel, and appropriate storytelling angle. Her thorough efforts to make distinctions among her recordings resulted in a wildly varied catalog of repertoire. She infused her singing with enormous attention to subtlety, nuance, and understated expression. This ability to distinguish appropriate differences among songs grew as her musicianship and interpretive prowess matured. Sarah Vaughan, who recorded Lee’s “What More Can a Woman Do?” admired Lee’s vocalism: “I like those nice breathy tones Peggy gets on her low notes.” Count Basie’s singer Joe Williams was likewise “captivated” by Lee’s rendition of “You Was Right, Baby,” which he first heard in a Chicago race record store that grouped Lee’s single among those of black artists.[6]

Lee’s ownership of her studio performance style grew enormously over the course of her career. Once, while working with Goodman, she expressed a desire to slow down and soften a new arrangement of Gershwin’s “But Not for Me,” but rather than concede to her suggestions, Goodman discarded the song entirely. Similar scenarios followed for Lee as her career climbed into new territory. Record producers at Capitol would eventually allow her to bring original songs and other material preferences to the sessions but generally reserved for themselves the final decisions about song lists and which masters would make it to an album. Likewise, as a young Capitol artist she would determine what approach to use for each song, but the bulk of the repertoire decisions would be producer-driven. Lee worked tirelessly to gradually grow her autonomy as an artist, but in the male-dominated music industry, her goal would take decades to accomplish.

From the Capitol Jazzmen session, one song in particular received extensive radio airplay. “That Old Feeling” mesmerized Lee’s fans because of the way she filled it with expression and meaning. She became so sought after from the success of this record that she hired her first manager, Carlos Gastel, to help shape her solo career. Shortly thereafter, Lee recorded a few sides with Bob Crosby and Orchestra, possibly in conjunction with a guest appearance on Crosby’s radio show. These included Harry Warren and Johnny Mercer’s song “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe” and Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke’s adorable song “It’s Anybody’s Spring.” The first began with the unmistakable sound of an orchestral depiction of a locomotive engine and train whistle (provided by a chorus of woodwinds) throughout the long introduction. When Lee entered, her youthful exuberance contrasted brightly against the more mature baritone voice of Bob Crosby. Lee’s lighthearted tones brought the song to life while Crosby’s counterpoint balanced her energy with intentional coolness. In “It’s Anybody’s Spring,” Lee sounded remarkably different, using more vibrato than usual, as if copying Bing Crosby’s style (for whom the song was written by Jimmy Van Heusen for the film Road to Utopia). This marked an interesting choice for Lee in interpreting this swing song—instead of her usual swing groove and spoken-on-pitch style, she mysteriously deferred to a previous style used when she had to sing in higher keys. Given her greater success with a more spoken style when singing swing, this rendition seemed out of place, amateurish, and inconsistent next to her more successful work, but it may have represented an experimental, transitional period when she was discovering her own voice. When readying herself for this session, she possibly had been modeling Bing Crosby’s film rendition because she sang it (note-for-note) exactly as the composer wrote instead of interpreting it with her signature stylistic touches.

In December 1944 Dave Barbour and His Orchestra entered the recording studio with Lee and recorded a charming ballad, “Baby (Is What He Calls Me).” Already, fans heard the mature Peggy Lee sound replete with thoughtful interpretation and expression packaged in a lower, slightly husky tone quality. Lee’s signature breathy vocal production would become her calling card, by which she would become known and loved worldwide. The first Barbour-Lee collaboration to be recorded, “What More Can a Woman Do?” was also undertaken at this 1944 session, and it fully utilized the breathy voice Lee had grown accustomed to using in favor of the earlier pure, high, and youthful tone resplendent with innocence and clarity. In coming into her own sound, Lee sacrificed some of the pristine finish heard in her most youthful records but gained a unique, earthy sound she felt was more her own. Lee’s penchant for smoking cigarettes intensified the huskiness of her tone. Over time this approach to singing was firmly cemented into Lee’s style, and there was no turning back. Fortunately for Lee, this novel sound exactly fit the persona she exhibited onstage, so she made the most of her unique musical niche.

“What More Can a Woman Do?” exemplified a slow and lovely original ballad and painted a picture of devotion typical of Lee’s lyric-writing style. So often, Lee approached songwriting from the standpoint of total commitment. While other writers may have stopped short of saying the obvious message (leaving a bit to the imagination), Peggy unapologetically wore her proverbial heart on her sleeve, holding nothing back. This self-revelatory lifestyle allowed her warmth and expressive depth to stay honest and vulnerable throughout her career.

In December 1944 Dave Barbour and His Orchestra recorded “A Cottage for Sale” by Willard Robison and Larry Conley, with Lee singing vocals. The master was never released as a single until it appeared in 2008 on Peggy Lee: The Lost ’40s & ’50s Capitol Masters album. This session marked Lee’s first enterprise as a solo Capitol artist. Lee’s initial entrance displayed temerity, and her voice bobbled slightly in a couple of places, which may have accounted for the fact that this track was cut from Capitol’s list of songs fit for release. Her usually secure centering of the pitch lapsed in a few places at the mercy of a fluttering vibrato. Still, much of the song was beautifully rendered, and Lee’s confidence seemed to sharpen as she progressed through it.

Shortly thereafter, Lee and a jazz quartet led by Dave Barbour recorded an original blues song called “You Was Right, Baby” that showcased Lee’s outstanding bluesy style and flirtatious expression. In this song (with Barbour’s quartet backing Lee’s vocals), both Lee and Barbour showed the peak of their performing abilities. Barbour’s guitar solo flaunted his ability to maintain an understated groove while exploring the tension between the flat and natural thirds that define the blues. He then tapered his guitar seamlessly back into the texture, making room for Lee to finish the piece. Lee balanced her true confidence in this style with artistic note choices, using a half-spoken, half-sung manner of communicating her text.

Peggy credited Great American Songbook composer, singer, and early Capitol executive Johnny Mercer for encouraging her to write her own songs and for suggesting that Barbour and Lee record their original songs at Capitol sessions. Agent Carlos Gastel had encouraged the Barbours to play their originals for Mercer, and Lee heartily welcomed the songwriting veteran’s suggestions and advice. As Iván Santiago-Mercado explained in his exhaustive Peggy Lee discography, Peggy remarked: “When they talked us into recording, we didn’t have any material, so Johnny said, ‘Do those things I heard—those are great.’ So we did them, and they were hits . . . ‘What More Can a Woman Do?’ and ‘You Was Right, Baby.’”[7] These two songs ended up on opposite sides of a Capitol 78-rpm single that spent ten weeks on the Disc Hits—Box Score best-seller music charts affiliated with Cash Box magazine. “You Was Right, Baby” peaked at number eleven.

In 1945 Peggy Lee joined Dave Barbour and His Orchestra to record another 78-rpm record, titled “Waitin’ for the Train to Come In,” by Martin Block and Sunny Skylar. This was issued for the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service along with selections featuring Dick Haymes and Frank Sinatra, in addition to other artists. This dragging ballad aptly described the painfully slow passage of time as one waited hour after hour and day after day for a loved one to return. The song stayed on Billboard’s charts for fourteen weeks beginning in November 1945, peaking at number four. Lee’s relaxed and easygoing manner, as mirrored in the companion ballad on the reverse side, “I’m Glad I Waited for You,” beautifully expressed the sentiment of a faithful woman awaiting the return of her beloved from the war. This latter song on the second side also attained chart positions, in March 1946, reaching number twenty-four on the Billboard list.

Billboard represented the gold standard of popular music’s record sales and radio spins—a song’s weekly ranking could be viewed in both parameters, and its overall success depended on the combination of both. Billboard measured, and still measures, popularity of a song relative to the other songs in the current week’s market. Billboard magazine featured its first “hit parade” in 1936, and a plethora of song charts followed in ensuing years. The charts soon reached around the world, and awareness of the fast-paced change occurring in American popular music spread internationally in part thanks to the weekly change-up of Billboard’s top songs, eventually known by 1958 as the Hot 100. Since then other charting services evolved in an effort to grow readership for other publications competing in the pop music industry.

In December 1945 Lee recorded “I Can See It Your Way, Baby” with the Dave Barbour All-Stars. This easy swinging ballad allowed Lee to purr her lyrics gently into the microphone. The song showcased Lee’s ability to persuade using her feminine charms and musical nuances, emphasizing the consequent phrase balancing the title, “but please see it my way tonight.” The song attained a level of sexy playfulness that Lee would build into her style.

At, presumably, the same session, Lee and Barbour recorded one of their best-known original hits, “I Don’t Know Enough about You.” This slow swing tune employed elements of the blues amid clever lyrics that explored an angle of male-female relationships that had not been described in other songs. Elucidating details about human interaction in new ways that resonated with millions of people seemed to be a challenge to which Lee often rose in her songwriting: “I read the latest news, no buttons on my shoes, but baby I’m confused about you . . . I know a little bit about biology and a little more about psychology . . . but I don’t know enough about you.” Through this song, Lee and Barbour succeeded in marrying music to lyrics in a way that pleased listeners and earned them millions of fans. Debuting on the Billboard charts in May 1946, the song peaked at number seven.

Lee and Barbour explored the process of writing songs together in various ways. Sometimes she would write lyrics and he would set the completed lyrics to music, as in “What More Can a Woman Do?” At other times she would compose words to complement Barbour’s simple musical ideas, and occasionally they would sit down together to work on composing words and music at the same time, contributing their thoughts and creating a song simultaneously, building upon one another’s ideas. John Chiodini expressed that his collaborations with Lee followed this same three-way songwriting paradigm, and Lee “said she loved this because this was the way she used to work with her first husband, Dave Barbour.”[8] Generally, Barbour would then arrange and orchestrate the music for performance or recording purposes. Later in her career, other members of the band (usually the pianist or big band conductor) would assume that responsibility.

In late 1945 Peggy Lee was called to a recording session in Hollywood in order to sing the vocal tracks for two Disney songs that were yet to be released in the film Make Mine Music, originally planned to be a sequel to the legendary 1940 Disney film Fantasia. While classical music claimed the equivalence of a leading role in Fantasia, popular music occupied an equally important role in the 1946 counterpart. Although Lee played no part in making this film, nor its soundtrack (Dinah Shore and The Andrews Sisters performed these songs on the soundtrack), this session independently created two promotional recordings for radio release ahead of the film. The songs “Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnet” and “Two Silhouettes” were accompanied by the Charles Wolcott Orchestra. The film represented a wartime compilation of short animated skits (much like Fantasia) put together to create a feature film, while Disney’s primary film staff finished serving in the army draft. Released in theaters in 1946, Make Mine Music was never reissued; instead it was sliced into ten shorts used in Disney’s televised shows.

In April 1946 Peggy’s solo career as a Capitol Records artist rose to new heights with “Linger in My Arms a Little Longer,” which became her fourth hit for the label. Dave Barbour and His Orchestra provided an easy swinging accompaniment to her gently crooning voice. According to Your Hit Parade Singles Chart, the song hit the charts in September and spent three weeks there, peaking at number eight. “Baby, You Can Count on Me,” the song on the other side of the 78-rpm record, was also recorded at the same session. This swing tune included a line in Spanish (a translation of the song title), which represented Lee’s first foray into music with strong Hispanic or Latin qualities. She would later explore this Spanish theme many times in original songs like “Mañana” and “Caramba! It’s the Samba.” Her keen ear for languages and interest in singing with heavy linguistic accents led Lee to record music highlighting various cultures more frequently than most other pop singers of her generation.

In July 1946 the Barbours recorded two of their original collaborations: “Don’t Be so Mean to Baby” and “It’s a Good Day.” The first was a slowly swinging song in which a woman begged her man to treat her with more kindness. It possessed a sense of earnest yet dignified pleading, as if Lee were asking for mercy on behalf of all ill-treated women. This version was held in the Capitol vaults for decades, finally seeing the light in 2008 when several unreleased masters were unveiled on the long-awaited album Peggy Lee: The Lost ’40s and ’50s Capitol Masters.

“It’s a Good Day” became an anthem for optimism long associated with Lee and would be used as a theme song for her radio show in forthcoming years. This wonderful up-tempo swing tune championed all that was fun and joyous about an ordinary day. In it, Lee encouraged the listener to embrace both the day and a positive outlook, to get going, and to be thankful for all the beauty and opportunities that this new day brought. The recording included a trumpet solo, a guitar solo by Dave Barbour, and a clarinet solo during the interlude before Lee returned for the final vocal reprise. “It’s a Good Day” first appeared on the Billboard charts in January 1947 and peaked at number sixteen. Capitol released this recording as a single in 1947, 1948, and 1951. Other labels, RCA Victor and Columbia, released their own competing versions of this Barbour-Lee composition. The song resonated so much with so many listeners that it remained relevant and cherished for multiple decades following its initial release. Other singers recorded it, including Dean Martin, Vic Damone, Perry Como, Bing Crosby, and the author of this book. Lee herself performed it on television four times as a duet with Bing Crosby, and Judy Garland performed it on her televised variety show in 1963. “It’s a Good Day” has appeared in several film soundtracks, including Scent of a Woman (1992), U Turn (1997), Blast from the Past (1999), World’s Greatest Dad (2009), and Pete’s Dragon (2016), and on television in episodes of Malcolm in the Middle, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, and Wilfred. Its universal appeal, catchy tune, and direct, positive message cemented its ongoing relevance for subsequent generations.

One song recorded at the same session, “I’ve Had My Moments,” ended up being rejected for commercial release but was eventually included as part of the 2008 posthumous album mentioned above. Lee’s overall performance was clean, expressive, and beautifully complemented by celesta, piano, and bass, but she anticipated her final note, singing it slightly early. This altered the timing of the pianist’s penultimate chord, which created an awkward musical moment and possibly accounted for the rejection of the track. Lee recorded “I’ve Had My Moments” five times in the 1940s, more than any other song. She recorded the song twice for radio broadcasts and two other times at Capitol for commercial release (July 1946 and November 1947), although only one of the three recordings made at Capitol was released prior to 2008.

On July 15, 1946, Peggy’s voice appeared on a recording of “A Nightingale Can Sing the Blues,” for which the Frank DeVol Orchestra was credited. Some uncertainty remains as to whether Lee actually attended the DeVol session or whether her vocal master from a June session, featuring Dave Barbour and His Orchestra, was inserted instead. Either way, the final product yielded a delightful symphonic rendering of a romantic, bluesy ballad with a flute soloist providing birdlike fluttering and calls in response to Lee singing the title lyric. Lee’s natural, gentle stroll through this storytelling song coaxed the listener into a virtual forest glade to observe the birds and trees so clearly painted in this orchestral landscape.

In July 1946 Lee recorded her fifth hit song, “It’s All Over Now.” Backed by Dave Barbour and His Orchestra, Lee imbued this medium-slow swing tune with a heartfelt story about falling prey to a lying beau. She navigated swinging semitones and employed fall-offs at the ends of notes to ornament her melody with jazz inflections teeming with authentic swing style. Halfway through, the band moved into a double-time feel, causing a ramp-up of energy and a sense that the music moved twice as fast, during which Lee naturally transitioned into a matching rhythmic sensibility. (This double-time feel was and still is a technique used by bands to add energy to the middle of ballads—the music’s harmony and melody move at the same rate as before but feel more energetic, with a busier undercurrent of rhythm and musical activity.) The music then tapered into the original slow swing feel for the end of this well-executed song. It entered the Billboard charts in November and attained number ten status.

Lee’s version of the scandalous song “Aren’t You Kind of Glad We Did?” by George and Ira Gershwin never made it to the Billboard charts, being banned from radio airplay by networks due to its lyrics being strongly suggestive of a sexual encounter. Moreover, two other duet versions of the same song were allowed radio play. Judy Garland and Dick Haymes performed it for the Decca label, and Vaughn Monroe and Betty Hutton recorded it for Victor. The duets allowed the male characters to assume much of the responsibility for the described indiscretions, leaving Lee’s solo version to show her simmering alone in the song’s shocking implications. Lee certainly did simmer in this recording, bringing a sensuous, unapologetic, and surprisingly open conversation about sex to the masses in a musical package. Lee forged new ground here in respect to recording subject matter universally deemed unsuitable for public discourse, and it would not be the last time. Whereas many other singers shied away from controversial subjects, Lee welcomed opportunities to explore new frontiers, even if they raised more than a few eyebrows.

In September 1946 Lee returned to the Hollywood studio at Sunset and Vine, again with Dave Barbour and His Orchestra, to record “He’s Just My Kind” by Floyd Huddleston and Mark McIntyre. This slow-moving ballad provided plenty of interpretive ground for Lee’s masterful ballad singing. Her uncanny knack for expression and nuance proved reliable here, yielding a rich example of sensitivity, musicality, and feminine charm with a distinctively jazzy tone. The song was released as a 78-rpm single with “It’s a Good Day” on the other side.

Also that month, Lee participated in a massive recording undertaking for a Capitol album called Jerome Kern’s Music, featuring a host of other artists. Lee recorded “She Didn’t Say Yes” for this project, which was originally released in 78-rpm format on four discs. It was later released as a 10-inch LP disc and as an EP (three 45-rpm discs). Johnny Mercer, Martha Tilton, The Nat Cole Trio, Margaret Whiting, The Pied Pipers, and Paul Weston were among the stars called in for this album, which may have been an effort by Capitol to proactively produce music by their top artists in anticipation of another recording ban.

Indeed, in October the American Federation of Musicians once again engaged in disputes with record companies over wages and contractual agreements, threatening a second debilitating strike. This caused the studios to schedule far more recording dates than usual for artists on their rosters. Fortunately, by October twentieth the parties had reached a settlement, and the recording schedule relaxed again. Four songs were recorded during this period by Peggy Lee and Dave Barbour: “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” “Birmingham Jail,” “Don’t Be So Mean to Baby” (again), and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” Recording masters of the first and last in this list were cast aside and never released until many decades later. Without the urgent need for new material, Capitol may have simply dismissed these recordings and moved on toward new, contemporary material. This session’s version of “Don’t Be So Mean to Baby” was released in 1948 (the previously recorded version was not released until sixty years later), and “Birmingham Jail” went public in 1951.

“Birmingham Jail” boasted an easy swinging rendition of this traditional American folk song. A refreshing new take on this well-known song lent the arrangement some historical value. The bouncing swing beat and Lee’s down-to-earth style lent new contemporary American relevance to the folk song genre as interpreted by the best swing musicians of the time period. “Don’t Be So Mean to Baby” was recorded again, replacing the horn section featured in the July recording with a guitar solo in October. The couple had booked a recording session in New York during a string of concerts at the Paramount Hotel and hired an unknown combo of performers. Both versions of this original song were vocally similar, although Lee presented the melody in a naturally expressive speech-like manner appropriate for the song’s moderately slow swing style, so each version inhabited its own unique character. Lee’s extemporaneous approach to recording jazz and blues possessed much freedom and originality by this point in her career, making the recording of identical iterations of the same song highly unlikely. Thus, the song versions possess differences, both in arrangement and in vocal delivery.

The couple recorded eight masters (all jazz or blues) during the New York recording session in October 1946. Four were ballads and four exhibited a medium swing feel. Music historian Iván Santiago-Mercado has asserted that these eight songs may have been intended for a Lee-Barbour album, as eight tracks often comprised a full album in the 1940s. However, no such album ever transpired for these masters, so some were stored in the Capitol vaults until their eventual release in 2008. These songs included: “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “It’s the Bluest Kind of Blues (Nuages),” “You Can Depend on Me,” “Trouble Is a Man,” “Music, Maestro, Please,” “Birmingham Jail,” and “Don’t Be So Mean to Baby.”[9]

Upon returning to Los Angeles, the Barbours lost no time in commencing with the recording routine. Recorded in November 1946, “Everything Is Movin’ Too Fast” hit the Billboard charts in February, peaking at number twenty-one, and gave the Barbour-Lee songwriting team their third hit. This medium-fast swing tune relied heavily on the blues and displayed clever lyrics about the ever-increasing pace of modern society. With its catchy melody and relevant words, the song found its niche in the canon of late 1940s swing music. It also may have served as a harbinger of trends to come—rock and roll was around the corner, and swing’s days were numbered. “Everything Is Movin’ Too Fast” sent the clear message that Lee wished the world would slow down to a more easygoing, comfortable pace.

In January 1947 Lee recorded “Speaking of Angels,” a romantic ballad played by Dave Barbour and His Orchestra, featuring the gentle accompaniment of flutes, clarinets, other subtle woodwinds, and muted horns. At the same session, they recorded the Gershwin/Buddy DeSylva classic “Somebody Loves Me” for a Capitol compilation album titled The Beloved Songs of Buddy DeSylva. Several other recording stars appeared on this album, including Johnny Mercer, Martha Tilton, The King Cole Trio, The Pied Pipers, and Margaret Whiting. This 78-rpm album contained four discs of music by some of the finest Capitol recording artists of all time, yet, unfortunately, it has never been released on compact disc for twenty-first-century aficionados to enjoy.

In March of that year, Peggy reunited with Benny Goodman to create a recording of “Eight, Nine, and Ten,” a simple swing tune with a melody consisting of a repeated tonic note. This time Goodman and Lee recorded with a smaller combo rather than with their previous eighteen-piece jazz orchestra. The Benny Goodman Sextet, featuring Dave Barbour on the guitar, proved to be in line with the trend of downsizing bands. This trend continued through the late 1940s and beyond, both for financial reasons and due to the fact that big bands generally were becoming less popular in favor of small jazz combos and rock bands. A simple rhythm section—guitar, bass, drum set, and a horn or singer—soon replaced the larger ensembles. Goodman later recorded another version of this song with his own voice providing the vocal part.

In April, Lee recorded “Chi-Baba, Chi-Baba” (also known as “My Bambino, Go to Sleep”), which climbed to number ten on the popular music charts. Perry Como’s version of this song reached number one. Lee’s version began with a gentle swing reminiscent of a rocking cradle; it then transitioned to a fast and furious double-time section, returning again to a lullaby-like finish with male backup singers providing support, singing the song title while Lee spoke a mixture of Italian and English to the infant receiving this serenade. At the same recording session Lee performed “Ain’tcha Ever Comin’ Back?” which was also recorded by Frank Sinatra. Both Sinatra’s and Lee’s versions spent one week on the Disc-Hits Box Score music chart.

On July 3, 1947, Lee and Barbour recorded another original collaboration, “Just an Old Love of Mine,” a slow ballad with a melancholic nostalgia for days and relationships gone by. Lee’s tender, unhurried, soft vocal approach to this musically rewarding piece left the listener in a reverie of blissful relaxation, as if she lulled her audience to sleep—something she was truly capable of doing, whether in a live performance room filled with people or in a recording studio. Other versions of this popular Lee-Barbour song were recorded for Columbia Records by Doris Day, for RCA Victor by Tommy Dorsey, for MGM by Billy Eckstine, and for Majestic by Dick Farney. Lee’s take on this ballad reached number thirty-four in the popular music charts and stayed for two weeks during the month of October. “Just an Old Love of Mine” and its popularity among studios and recording artists furthered the Barbour-Lee songwriting team’s credibility and clout in the pop songwriting business.

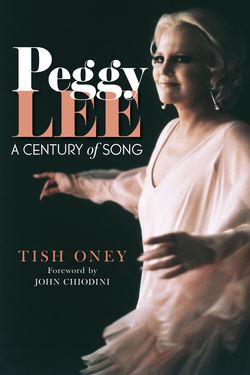

Peggy Lee and Dave Barbour in rehearsal. Photofest.

Although Peggy was in wonderful voice during this recording date, her lovely performance of another song, “Why Should I Cry Over You,” remained locked in Capitol’s vaults until the album Rare Gems and Hidden Treasures was finally released in 2000. Joined as usual by Dave Barbour (this time with a group of unknown musicians billed as the Dave Barbour All-Stars), Lee displayed exuberant swing in full-voiced style.

Why so many seemingly high-quality masters remained unreleased for over five decades seemed peculiar, indeed. Lee, however, had little decision-making power in regard to what masters landed on albums or singles that Capitol released for sale or radio broadcast. At this point in her career, Lee, along with countless other artists, had to defer to Capitol’s producers and company executives who decided which masters to use and which to toss. Being female made her influence even smaller with regard to the record executives’ decisions. Several of Lee’s original songs were recorded at Capitol sessions but never made the final cut for albums or singles, although she was fortunate to have been allowed to release some of her own compositions early in her career. Her songwriting prowess was already proven by the number of other mainstream artists (both at Capitol and at competing labels) who recorded her songs, namely Sinatra, Martin, Day, Vaughan, Cole, and others. That her originals had produced genuine hits may have further persuaded the record producers to include her songs in their album releases.

“‘Is That All There Is?’ is not just the title of a hit song recorded by Peggy Lee . . . It’s also a question long-time Lee collectors have posed throughout the CD era.”[10] Peggy Lee fans all over the world rejoiced when the albums Rare Gems and Hidden Treasures and The Lost ’40s and ’50s Capitol Masters were finally made available to the public. EMI took on the latter project with cooperation from Capitol Records archivists and Lee’s granddaughter Holly Foster-Wells leading the charge. These archived recordings bore merit of their own and constituted an important additional catalog of Lee’s output. Scores of previously unheard tracks that Lee had recorded many decades earlier finally took their rightful places in her canon of recorded music. Aficionados and scholars of music from decades past obtained a much greater sense of Lee’s total musical and artistic output when the plethora of unreleased songs gained their due hearing alongside well-worn recordings her fans remembered as big hits. Music critic Jack Garner wrote of this posthumous project: “Through the 39 tracks, Lee stokes the fires that ultimately lead to ‘Fever,’ her late-’50s megahit. If you only know Peggy Lee from her later hits, check out this early material. This lady was a winner from the get-go.”[11] Nashville music writer Ron Wynn asserted that the same collection revealed “Lee’s deep blues roots [. . .] her ease working with small combos or larger orchestras and her ability to elevate novelty fare and disposable period piece bits into memorable, explosive productions. Lee . . . displayed outstanding phrasing and enunciation and covered songs from Irving Berlin, the Gershwins and Cole Porter. It’s rare so much quality music remains obscure, but there’s absolutely nothing disposable or generic about anything included.”[12] New York Sun’s Will Friedwald gushed: “It is unimaginable why Capitol Records would have kept these gems in the can for almost 65 years; they are considerably better than a lot of the contempo songs the label did release during these years.”[13]

The first Capitol Records era in Peggy Lee’s career spanned the years 1946 to 1952. This was followed by a five-year stint with Decca beginning in 1952 and ending in 1957, after which she moved back to Capitol for an impressively long stretch from 1957 to 1972. No other female artist held a Capitol recording contract for as long as Peggy Lee held her consecutive contracts. This reality proved the immense value Peggy brought to the Capitol brand and to the catalog of American popular music that was enjoyed each day through radio broadcasts, jukeboxes, and records played in the homes of her adoring fans. As early as 1947, Peggy Lee was well on her way to becoming the jazz and pop diva she came to embody.