Читать книгу Peggy Lee - Tish Oney - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Voice for the Big City

ОглавлениеIn May 1920, just three short years after the first jazz record was made by the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a little girl who would forever change the development of jazz singing and American popular music was born in Jamestown, North Dakota, to Marvin and Selma Anderson Egstrom. Raised on a farm in the Midwest with no clear alternate pathway provided for her, Norma Delores Egstrom dreamed of becoming a professional singer like those she admired on the radio. Years later she shared in a personal interview that Maxine Sullivan, the African American singer who recorded the Scottish folksong “Loch Lomond” for Claude Thornhill’s band, exerted a strong early influence upon Norma, albeit merely over radio waves: “She sang very lightly, like a painter using very light brush strokes. She communicated so well that you really got the point right away.”[1]

Norma’s mother sang beautifully, played the family piano, and encouraged her children to make music together at home. A classmate of the Egstroms commented that Norma’s older sisters Della and Marianne had also possessed lovely singing voices but lacked the motivation to pursue music as a career.[2] Without any formal musical training, early in her teens Norma sought opportunities to sing in public. These community gatherings and talent shows eventually yielded her an opportunity to perform as a soloist on live radio close to her home in Jamestown. Introduced by a friend to Ken Kennedy, the music director at WDAY in Fargo, Norma was scheduled to perform live on his show, but Kennedy insisted she change her name first. Moments before she began her song, he nicknamed her “Peggy Lee” and the name stuck.

Lee sang at school throughout her teen years and picked up a job working as a waitress at the Powers Hotel Coffee Shop in Fargo. She was soon performing two shows a day plus late shows on weekends at the establishment with organist Lloyd Collins, who regularly played requests for patrons. With this on-the-job training, she quickly built her repertoire to include a wide variety of music, from old folk songs to modern jazz and contemporary popular songs.

By the tender age of seventeen, Lee had grown restless in rural North Dakota. Her thirty-nine-year-old mother had died when she was four but remained a muse throughout the singer’s musical life. Growing up in a troubled household with her alcoholic father and abusive stepmother, Min Schaumber, with whom she had a very strained relationship, Peggy yearned for independence. Loving the new popular music, which was strongly tied to jazz and swing, and possessing relentless ambition, she auditioned for a spot with Sev Olson’s band in nearby Minneapolis, which led to a stint with a nationally touring dance band led by Will Osborne. She set off with a couple of bandmates for southern California as soon as an opportunity arose. In 1939 Lee managed to secure a performing date at The Doll House in Palm Springs and recalled that the noisy crowd would not quiet down enough for her to be heard over the din, so she instinctively sang more softly into the microphone: “I knew I couldn’t sing over them, so I decided to sing under them. The more noise they made the more softly I sang. When they discovered they couldn’t hear me, they began to look at me. Then they began to listen. As I sang, I kept thinking, ‘softly with feeling.’ The noise dropped to a hum; the hum gave way to silence. I had learned how to reach and hold my audience—softly, with feeling.”[3] In a later interview, Lee described the concept of dynamic contrast as “one of the interesting things to me about music in general—how to change the colors and the moods and how to build up like an ocean wave and let it wash away and then be very quiet.”[4] As patrons paused and became hushed in order to hear her, she discovered her knack for drawing listeners in by singing quietly instead of by increasing her volume. Fortunately for Lee, an influential hotelier, Frank Bering, witnessed this magical performance and offered Lee her next job at The Buttery Room, the nightclub inside his Ambassador Hotel in Chicago. It was in this room that Benny Goodman first heard Lee perform, shortly after his singer, Helen Forrest, had left the Goodman band. This stroke of good fortune placed Lee literally at the front of the most influential band of the swing era. Needless to say, her career was off and running.

Lee later described the sometimes difficult Goodman as a taskmaster whose musical demands were the highest of any bandleader in the industry. Goodman laid down strict rules each band member was expected to maintain including mandatory curfews, brutal tour schedules (one year the band performed fifty one-night-only concerts in succession, in different cities), and intolerance for imperfect musicianship. Goodman lived with music as his highest calling and took that calling very seriously. He expected his musicians to attain the highest possible level of musical execution for both live performances and recording sessions. While this may have created a difficult workplace situation for some, it lifted the musical quality of Goodman’s band to admirable heights.

At first glance, Peggy Lee may have appeared to be just one of many attractive female singers fronting important big bands of the early 1940s. When she first joined the Goodman band as a replacement for soprano Helen Forrest, Lee dutifully sang in those same high keys. In that year’s recordings, Lee’s high-pitched, youthful tone matched the lightness and sunny approach of many other leading big band vocalists. Her early success with a lighter, higher tone proved Lee’s versatility and raw talent, even without formal training or professional tutelage. When finally given opportunities to show off her lower, softer, bluesy approach though, her signature style began to bloom.

Lee first recorded with the Goodman band on the Okeh label owned by Columbia Recording Corporation. Her recordings from 1941 revealed the uncanny pitch precision, easygoing rhythmic sense, and relaxed delivery the artist would become known for throughout her life. Even with the higher relative range of this repertoire as compared with her later material, her exquisite tone quality was equal to or exceeded that of other popular singers of the period; plus she had an approach that was singular and original. She wasn’t just talented, though. She was unique. While often compared with Billie Holiday, Peggy Lee possessed an unequivocally lighter and more vibrant voice in the early phase of her career. The pure, youthful, and healthy voice in Lee’s 1941 recordings surprises those whose familiarity with Lee centers around her later radio hits from the 1950s and ’60s. Over time, smoking took its toll on her pure vocal sound, and its nascent clarity gave way to the darker, slightly husky quality for which she became famous.

One early recording, “Elmer’s Tune,” made in August 1941, sported a bouncy swing feel with a lightness and jovial quality that Lee’s teenaged voice suited perfectly. The chromatic melody proved to be no challenge whatsoever for the pitch-perfect singer. Benny Goodman’s lighthearted clarinet solo toward the end of the recording yielded a lovely response to Lee’s cheery vocal chorus. Later that month the band entered the recording studio again to lay down “I See a Million People (But All I Can See is You).” This song possessed a melody featuring a couple of surprising pitches and matching harmonic turns in its returning theme.

The standard song delivery for the Goodman band (and many others in the swing era) involved playing a song (or a portion of it) instrumentally first, with the entire orchestra, then transitioning to a section for leading in the vocal soloist, often facilitating a key change. Such was the case with “That’s the Way It Goes,” recorded in September 1941. Following an instrumental reading through the first two iterations of the opening theme during which Goodman played the melody, an extended transitional section preceded Peggy’s sung entrance. After Lee’s gentle vocal chorus displayed an even, well-produced tone, Benny Goodman and the band repeated the tune more forcefully with a short call-and-response clarinet solo alternating with the band’s answers. This coupling of roles functioned nicely as a coda to finish the song with a neatly arranged ending, furnished by the now legendary big band arranger Eddie Sauter.

As Lee gained more experience with the Goodman band and became more comfortable with her voice’s expressive qualities, she began to embrace the emotion of each new song. In October 1941, Lee and the Goodman band recorded Duke Ellington’s classic “I Got It Bad (and That Ain’t Good).” Lee delivered a particularly feminine, pure rendition of this standard, in keeping with her youthfulness. Her musical precision and rich tone quality revealed her growing skill and ease with which she tackled the pressure of the recording studio. Although the simplistic approach to this bittersweet text sounded light and carefree in tone quality, the final eight bars suggested Lee’s innate connection to the song’s dark undertone. Demonstrating the journey from innocence in the sweet, mellifluous beginning section, Lee shifted to a voice of tragic experience in the final closing. Goodman’s swinging improvised solo dripped with jazz style and overt blues wailing appropriate for the King of Swing. The band also swung masterfully, with no hint of rushing or overplaying. The incredible control required for an eighteen-piece band to execute meticulously timed swing in a manner that eased off each note without affecting the tempo filled this recording with the authenticity exclusive to the top band from the swing era.

This recording represented the first of many songs to reach the popular music charts during Peggy’s involvement with the Goodman band. The single was released almost immediately after it was recorded and hit the music charts on the fifteenth of November 1941. Unlike today, songs or “sides” (three-minute single songs that occupied a whole side of a ten-inch-wide, 78-rpm record) were recorded and released relatively quickly, without the long processes of editing, mixing, and mastering that require many months of production in modern music recording. Recordings were presented to the public via 78-rpm singles, in jukeboxes, and on the radio as basically live versions of songs, even though a few takes might have been necessary to glean the best performance. Today even live albums are meticulously edited, mixed, and mastered before the public ever hears a note.

In the swing era, recorded music truly represented the newest offerings of modern songwriters, as songs may have been delivered by their composers or lyricists to bands on the same day they were to be recorded. Because bands were in the business of delivering the latest swing music to the public through both performances and records, frequent recording dates were the norm. Bands recorded a few times per month on average, and session musicians were paid modest fees for a day’s work. These musicians were, of course, expert sight-readers, being required to perform music they had never seen before with accuracy, grace, and expertise. Many long careers were made for instrumentalists in New York and Los Angeles (where the major recording studios operated) who could read music well.

“My Old Flame” appeared on the Goodman band recording session list in October 1941. This blues-inflected ballad from Paramount’s Mae West film Belle of the Nineties went on to become a jazz standard recorded by many singers after Lee. This song possessed a gently walking bass line, understated, with soft dynamics (until the more raucous trumpet solo halfway through), and a tenderly delivered melody and lyric by a golden-voiced singer. Here stood a preview of Lee’s later penchant for singing at an extremely soft volume. The band joined her in creating a gentle, quiet form of swing that pleasurably moved as one unrushed, plaintive voice. Goodman’s brief, high-pitched clarinet solo transformed toward the end of the recording into a fleeting double-time flurry, adding a passionate contrast to the previously easygoing, dreamy stroll of the song.

Irving Berlin’s “How Deep Is the Ocean” enjoyed a medium swing interpretation by Goodman and Lee that stood firmly among the definitive versions of this famous tune. The introduction opened with an ascending minor riff played first by the low brass, then passed to the saxophones and finally to the trumpets at one-measure intervals over a steady bass walking quarter notes. Lee entered in a new key following this long instrumental storyline. Her lyrical contribution revealed beauty in the poetry Berlin infused within this timeless song. Lee’s respectful delivery of the text kept with the tradition of the period. Lyrics were never interpreted by singers fronting a big band but were simply delivered as purely and beautifully as their voices allowed. Interpretation and stylistic affectation were deemed inappropriate for singers of the big band genre. These permutations began to come into common use mostly by singers such as Billie Holiday, whose skills became best known within the context of the small jazz combo. As was typical of song recordings from the big band era, this song’s wonderful lyrics were not repeated but only presented once, with instrumental openings and endings surrounding the prized lyrical content.

Using understatement, tenderness, and thoughtful phrasing to express song lyrics, Lee found ways to cover her songs with a robe of alluring sensuality. Even as early as her first few sessions with the Benny Goodman Orchestra, Peggy exhibited musical restraint, as heard in her first recorded hit, “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place” by Howard, Ellsworth, and Morgan. Her minuscule slides from note to note connected the lyrics and tones in an elegantly controlled, sophisticated manner. Lee’s conversational quality revealed a thoughtful artist developing a keen ability to communicate emotion and depth throughout the course of a song. She successfully matched the band’s lighthearted, bouncy tone of this swing arrangement, even though the lyrics suggested that a more serious approach might have been appropriate. Later in her career Lee would surely have modified her approach to this lyric in a way that preserved its heartbreaking sentiment, but she had not yet learned to assert herself in insisting that her arrangements consistently respect the intention of the text. As a result this recording exhibited a triteness and vocal indifference uncharacteristic of her later work, manifested in the vividly cheerful way she sang about being passed over for another lover. Nevertheless, the music prevailed, and the band’s relentless swing led to a warm reception by the public and a hit song on the radio. Recorded November 13, 1941, “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place” debuted March 7, 1942, hovered in the pop music charts for fifteen weeks, and peaked at number one.[5] This marked the first of many number-one hits Peggy Lee would enjoy throughout her long career.

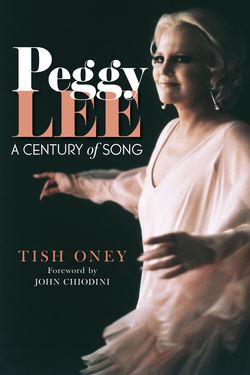

Peggy Lee, 1943. Photofest.

“Somebody Nobody Loves” followed suit as another sad story put to a carefree swing. We might wonder why the lyrics of such songs were not paired with more sensitive, somber musical accompaniment. These songs balanced out the happy, optimistic songs of the swing era without sacrificing the all-important dance beat. Lyricists knew that if they could mold their texts to fit a danceable beat they had a better chance of hearing them performed by the most popular bands. In the early 1940s dance halls provided a primary form of entertainment, and American popular music was synonymous with swing. Most songs during this era required a danceable beat, regardless of the mood of the text. As a result, this period included a great many songs whose music would surely have been more somber if composed in a later period.

Most importantly, music from the early 1940s intentionally maintained a lighthearted and joyful mood to provide the American public with a needed distraction from reality. The shock and horror of World War II pervaded the everyday lives of American citizens as well as men and women serving in the armed forces. Performing artists, recording artists, and film actors often offered their services to the USO to support American soldiers, and upbeat songs played by leading swing bands served this cause very well. Inspiring and encouraging servicemen and their families back home became a ministry performed by American dance bands. Bing Crosby, a friend of and frequent collaborator with Peggy Lee, served the USO faithfully, and Lee did her part by providing upbeat music at wartime for radio and for American families awaiting the return of their beloved soldiers. As the war dragged on, optimistic dance music became a valuable, although perhaps ironic, offering to the American public provided by performing artists.

On the same day that Lee recorded the ironically upbeat “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place,” she also recorded the Gershwin standard “How Long Has This Been Going On?” from the Broadway musical Rosalie, with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. This gently swinging ballad allowed Lee to showcase her innate expressive compass. She supported her voice with efficient energy, yielding superb resonance and tonal purity that suggested years of formal training. Lee’s lovely rendition of this Gershwin gem allowed her to stand among the many other revered recordings of this song, including Lena Horne’s 1945 recording replete with a light, fluttering vibrato that contrasted with Lee’s slightly cooler, more emotionally charged version.

“That Did It, Marie,” a heavily swinging tune recorded the same day, gave both Lee and Goodman an opportunity to allow their swing style to rise to a new level. Lee bent notes, employed ascending and descending smears and falls, and wrapped a thick sense of easygoing style around the humorous narrative personifying various band instruments. The lyrics described a saxophone’s “jumpin’ jacks” and urged “jump, jump, jump it through that trumpet.” Goodman later poured on the blues during his improvised clarinet solo, wailing lines that drew the band into exuberant swing. Lee’s vibrato (albeit light and gentle) came through as a hallmark of these early recordings. As her career developed, she would use less vibrato and focus more on smoothness of tone, phrasing, and rhythmic timing.

Later that same month, the Goodman band recorded “Winter Weather,” which peaked at number twenty-four on the popular music charts. For this vocal duet, Lee sang the first chorus followed by an instrumental trip through the song. Benny Goodman then provided an improvised chorus, alternating with arranged passages for the full band. Following that, the male singer for the Goodman band, Art London (who later modified his name to “Lund”), sang the second verse before the band played a four-bar transition and Lee sang the reprise. This bouncy, optimistic song included interesting key changes, calling to mind the lyrical descriptions of unpredictable weather.

In December 1941 Lee and Goodman reentered the recording studio to record Johnny Mercer and Victor Schertzinger’s “Not Mine,” from the film The Fleet’s In. This song, while still requiring a higher vocal range than Lee preferred in later years, gave Lee the opportunity to exercise a more womanly tone that sounded more at home in front of the microphone. Goodman recalled that when first hired, “[Lee] was so scared for about three or four months, I don’t think she got half the songs out of her mouth.”[6] Lee was not the only one growing more comfortable with their collaboration. During the improvisational solo for this song Goodman employed a double-time technique (briefly playing notes twice as fast), exhibiting exemplary control and obviously enjoying himself.

“Not a Care in the World,” from Broadway’s Banjo Eyes by John Latouche and Vernon Duke (arranged by Eddie Sauter), was recorded by the band in December 1941. This easygoing swing tune marched ever onward with Benny Goodman providing the opening melodic statement on his clarinet, unlike the contemporary tradition of a vocalist singing the first iteration of a song’s melody. Keeping the focus on himself, Goodman often commanded the attention of audiences by being the first soloist featured, even if just to perform the melody ahead of the singer. This song was remarkable in its form, as it departed from the usual eight-bar sections. The opening theme (called A) was nine bars in length, so in this AABA format (in which B represented the contrasting theme or bridge), it yielded 9+9+8+9 measures in its total form, equaling thirty-five measures instead of the conventional thirty-two. While more typical for an art song five decades later, a song departing from an eight-bar main theme was highly unusual for 1940s popular music. The song also employed a melody that illuminated Peggy’s ability to sing low passages with ease.

Also that month, Peggy and the Goodman band recorded the Johnny Mercer/Harold Arlen standard “Blues in the Night,” from the Warner Brothers film by the same name. Lee’s rather conservative rendition of this blues song represented an excellent example of the early Peggy Lee sound. In her later years, her approach to the blues became much earthier and more dramatic, and her voice more husky, breathy, and prone to quieter singing.

Accustomed to the rigors of having to share Capitol’s studio time among many active artists, Lee recorded Rodgers and Hart’s “Where or When” from the Broadway musical Babes in Arms, on Christmas Eve in 1941. Recording schedules also frequently stretched late into the night when deadlines loomed so that projects could be finished before opening the studio for a different artist or band the next morning. Peggy’s “Where or When” peered into the future by revealing her use of an ultra-soft vocal technique that, years later, became Lee’s go-to strategy for making audiences listen. Her enchanting and gentle approach on this early recording melded perfectly with the delicate celesta and piano accompaniment. The celesta was an instrument often used on radio shows and in certain types of ballads during this time period. Played at a keyboard, the celesta contained a series of metal bars struck by felt hammers operated by keys, yielding a heavenly tinkling sound. This tone quality commonly accompanied children’s music, holiday music, and ballads with dreamlike texts to create an ethereal quality. Lee’s understated approach and the slow, steady pace of this ballad suggested that the tenderness of a lullaby was the desired effect. Throughout the song, Lee provided a remarkably even softness and haunting beauty, spanning a wide range beyond an octave. She effortlessly traversed the difficult final phrases that slowly ascended stepwise all the way up the major scale. This recording’s attention to vocal nuance and tonal consistency throughout a wide range represented Lee’s finest example of vocalism to date.

That same day in the recording studio, Lee and Goodman laid down a track of the Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields standard “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” from Broadway’s International Revue. Goodman bounced along through the opening melodic statement before Lee entered with an uplifting statement of her own. She managed to sing several low F’s (far below the range of a soprano and lower than most altos were required to sing) without difficulty. Her stylistic choices to change a pitch here and to bend a note there yielded an enjoyable, rewarding romp through a very well-known song. Her sense of syncopation was also rich here, as she anticipated downbeats by selectively choosing to enter an eighth note early on some occasions, as was, and still is, respectful of the jazz or swing style.

“The Lamp of Memory” was a nostalgic tune that received its due attention by the Goodman band during their first known studio date of the new year in January 1942. Far from being a swing song, this romantic ballad rapt in melancholic wishful thinking had Peggy singing with a great deal of vibrato and old-fashioned sentimentalism. At that same session, Lee joined Art London again in a duet from the Paramount film The Fleet’s In, singing “If You Build a Better Mousetrap.” This clever tune by Johnny Mercer and Victor Schertzinger served as an adorable cat-and-mouse romp for any pair of songbirds. First Art lectured on all the techniques and tricks he knew to attract women. Peggy then described her recipe for dating success in a similar way, and both ended their litany of tips with the questions: “Why doesn’t anything happen to me?” and “What’s the matter with us?” During this storytelling foray, Lee showed her predilection for genuine swing feel, a keen sense of humor, and a vocal approach that was more spoken on pitch than sung. This last point described Lee’s manner of singing throughout most of her life. Although that same day in the studio she sang with a more classical, traditional approach for “The Lamp of Memory,” the duet revealed her preference for her unique style of storytelling.

Lee and Goodman recorded the ballad “When the Roses Bloom Again” at the same recording session in January. The inclusion of nostalgic pieces like this in a mainstream swing band’s recording session (and live performances) illustrated the balance often sought by bands and recording companies to present to the public not only new, forward-looking material tailored toward youth, but also songs that appealed to those established, mature music consumers preferring music in the style of yesteryear. In this way the Goodman band appealed to more than one demographic. In catering to mature audiences, Peggy tended to modify her vocal approach toward the same classical technique she employed for tunes like “The Lamp of Memory.”

Recorded in February of that year, the somber song in a minor key “My Little Cousin” began with an ethnic folk flourish by the trumpet reminiscent of traditional Jewish music. This ethnic folksong flair returned at the end of the song, during which Lee and Goodman performed together several times in well-rehearsed harmony a particular type of ornament (a mordent, or turn) specific to that cultural style. Considering Goodman’s Jewish heritage and upbringing, the inclusion of this song may not have been surprising to some, although it certainly was not a frequent sound in commercial recording sessions of the early 1940s. Interestingly, the original Yiddish lyrics of “My Little Cousin,” which expressed frustration and disillusionment on behalf of America’s Jewish immigrants, were drastically toned down in translation. Instead of rocking the image of Jews in America, the text’s focus changed to that of a romantic relationship. While Goodman clearly demonstrated a desire to reflect his ethnic heritage in his music, the reality of political stress likely influenced Capitol’s repackaging of the song’s message.[7]

This was not the first time Benny Goodman advocated for diversity and inclusion. Several years earlier, Goodman crossed racial barriers by organizing a mixed-race trio and quartet for recording and performing. Goodman had hired Teddy Wilson, an African-American pianist, and praised him as the finest jazz pianist in the business.[8] The trio and quartet also featured Caucasian drummer Gene Krupa (who had already performed in the Goodman band) and African American vibraphonist Lionel Hampton. Goodman was known throughout the music business as leading one of the first racially integrated music ensembles in American history, so his decision to record a song with strong Jewish inflections shortly before the U.S. entry into World War II was neither surprising nor insignificant.

“The Way You Look Tonight,” a classic standard by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields, fell onto the list of songs to be recorded by Goodman and Lee in March 1942. This delightful love song from the RKO film Swing Time fit Lee’s knack for imbuing a ballad with beauty, tenderness, and sincerity. In this recording she gave attention to each tone, enlivening each note with grace and innocence. She slightly delayed several phrase entrances as though in the midst of an extemporaneous conversation. This manner of backphrasing, either intentionally delaying the start of a lyric phrase until after the musical phrase has already begun or anticipating the musical phrase by singing the lyric early, was an expressive technique first used by Billie Holiday, who learned it from saxophonist and mentor Lester Young. Lee followed suit quickly, staying at the forefront of stylistic trends. Certainly aware of Billie’s style, Lee possessed her own expressive compass as well. Creating a trancelike atmosphere within the song, she wove her musical lines in a spellbinding fashion mirroring the text. The impression she gave through her relaxed gliding from note to note suggested hypnosis experienced while gazing at her lover, yielding a dreamlike desire to remember that moment forever. The celesta accompaniment added a sparkling twinkle of magic to the total sound on the recording, and this meshed well with Lee’s delicate voice. The song peaked at number twenty-one on the pop charts in June of that year.

Irving Berlin’s “I Threw a Kiss in the Ocean” yielded a charming swing tune for Lee to explore with Benny Goodman and his big band at one of their March 1942 recording sessions. It opened with a full band fanfare followed by a brief, energetic clarinet solo punctuated by trumpet hits, the low brass provided the finish to the introduction with a vocal lead-in transition driven by the saxophones. The trumpets continued to punctuate the melody sung by Lee in alternation with low brass responses, as though she were having a conversation with separate sections of the band. This turn-taking texture created a sense of equality between the band and the singer that contrasted with the more common texture of lead vocal backed by accompaniment that prevailed during this period. This recording illustrated Goodman’s and Lee’s willingness to explore different musical textures in their recording output. A piano solo provided additional textural contrast, followed by a trombone solo and then a clarinet improvisation offered by Goodman. The band rejoined for a big finish, with a tasteful extension played by the piano and walking bass.

Recorded in March 1942, “We’ll Meet Again” by Ross Parker and Hughie Charles hit the pop music charts in May, peaking at number sixteen. This nostalgic but lightly swinging song gave Lee a chance to share her optimistic spirit and encouraging personality. The lyrics promised a future meeting after time spent apart from one’s dearest friends. For many years this song has continued to grace retirement parties, family reunions, and class reunions as an anthem of hope for enduring friendship. Having resonated strongly with older music fans drawn to the music of yesteryear, the song enjoyed significant popularity in the early 1940s and beyond. Lee approached this lyric in a straightforward and sincere manner, showering her sunny disposition upon the music to match the hopefulness contained in this sentimental text.

“Full Moon” (also known as “Noche de Luna”) was recorded on the same date in March. It arrived on the music charts in June and peaked at number twenty-two. A moderately fast song, it opened with a heavily swinging big band sound followed by a gently moving clarinet solo, and after another interjection by the full band, it tapered into a more delicate vocal tune perfectly suited for the vulnerable feminine voice of the young Peggy Lee. Beginning the vocal chorus in an up-tempo Latin style and falling into swing feel eighteen bars later, the tune provided both exotic and laid-back flavors for fans of different styles. The Latin flair returned at the very end to provide unity and cohesion to the piece—an ode to the power of the moon to influence romance. Lee and Goodman found a good match for their talents in this sentimental swing song blending both older and newer styles.

“There Won’t Be a Shortage of Love,” an unissued single finally released on the Columbia Legacy series in 1999, came into being in March 1942 courtesy of Lee and the Goodman band. This cute ditty followed the format of several other swing songs recorded by this band, as it was arranged by pianist Mel Powell, who held the responsibility of arranging several of their recorded songs. Goodman offered a taste of the melody in a brief solo following a fairly quiet opening with Mel Powell playing flowery piano lines amid short brass hits and a swath of soft padding by saxophones. Powell’s tasteful arranging ability showed a great depth of variety, giving young Lee a sense of what might be possible for her own songs and arrangements later in her career. The timely lyrics described various food shortages, rising taxes, and other sacrifices suffered by Americans during the lean years of World War II. As always, this swing band managed to keep even wartime messages light and danceable, pointing to the abundance of love to be enjoyed in the midst of such relative lack. Even with this extremely positive spin on the plight of working American civilians, the song was never released to provide the encouraging message it sought to deliver.

In May 1942 the Goodman band entered the studio again with Lee to record Irving Berlin’s classic song “You’re Easy to Dance With,” from Paramount’s Holiday Inn. With the success of Fred Astaire’s timeless version taken directly from the movie musical, it is no mystery why this somewhat less polished rendition was never released. Although an adorable song, the arrangement did not lend itself to improving the original enough to endure as an alternate version.[9] Although Lee sang her vocal line acceptably, her opening phrases sounded less stable and confident than usual, and she seemed to be less vocally prepared for this selection. This song may have been cut from an album (or a series of singles) before a final edited version was made. Masters never meant to be heard by the public tended to be less polished than fully rehearsed, edited recordings. Even before the days of painstaking, months-long editing processes that current songs undergo, major studios like Columbia and Capitol went over final cuts with a fine-tooth comb to ensure a high standard of quality.

The slow, charming ballad “All I Need Is You” that Lee and the Goodman band recorded in May 1942 sounded as if it belonged to years gone by rather than to the leading styles of the day. Deftly sung by Lee (even in the passages befitting a soprano), the song included wide melodic leaps landing the singer in a higher vocal range than was usually performed in jazz and swing. A jazz or swing song’s performance keys were, and still are, generally selected with the singer’s spoken voice range in mind. This ensured that the lyrics came through clearly and differed from the emphasis of classic genres like opera, where the power of the voice was more important than the clarity of lyrics. Since jazz, swing, and popular singers’ voices were amplified in performance and recording, they could place a greater emphasis on lyrics. As this need to amplify one’s own voice quickly waned at the dawn of the technological age, voices with excess vibrato and projection fell out of vogue. By contrast, soft, sultry voices like Lee’s became popular, and gentler vocal stylization began to evolve among the popular, swing, and jazz set.

Along with many other bands, the Goodman band participated in war bond rallies in New York to assist with the war effort. Returning to New York to perform at the Paramount Theater in May 1942, Lee and Goodman wowed audiences with their renditions of “Where or When” and “Sing, Sing, Sing,” Goodman’s swing era anthem. Back in 1937 the Goodman band had recorded this Louis Prima standard, clocking the recording at over eight minutes—way past the usual three-minute limit for radio play. The song was instrumental in continuing the swing frenzy begun on August 21, 1935, at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles. Goodman ushered in the swing era that evening with the national radio broadcast of his live concert at this colossal dance hall attended by twenty thousand dancers. With the help of AM radio’s long wavelengths traveling hundreds of miles farther than modern FM radio, and a string of DJs devoting their airtime to broadcasting the concert, the event blanketed the nation in swing. One of the most influential concert performances in music history, Goodman’s Palomar debut ushered in a whole new genre of popular music and made Benny Goodman one of the first American pop culture stars. Even though other bands (notably Duke Ellington’s) had been playing swing for years already, the public awareness and appreciation among white audiences was sealed that evening. Goodman later commented about the song: “‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ (which we started doing back at the Palomar on our second trip there in 1936) was a big thing, and no one-nighter was complete without it.”[10] Thereafter, Goodman’s audiences expected to hear the song whenever he appeared. New York’s Paramount Theater crowd responded with the usual appreciation accorded to this era-defining hit.

During an interview with George Christy in 1984, Peggy Lee related that she was a fan of Lil Green, “a great old blues singer.”[11] Being in the habit of playing Green’s recording of “Why Don’t You Do Right?” repeatedly in her dressing room at the Paramount, Lee heartily accepted Goodman’s offer to create an arrangement of it especially for her. In July 1942 Peggy and the Goodman band entered the recording studio to record the song that would change the trajectory of Lee’s career. Charting in January 1943, Lee’s rendition of the song stayed on the popular music charts for nineteen weeks, peaking at number four. The success of the recording led to a spot in a film for Lee and the band. Their scene from Stage Door Canteen, in which they played the song in its entirety, became a famous moment in music history, announcing the arrival of Lee as a new solo recording artist. The vital importance of this recording to Lee’s ensuing career cannot be overstated. Her performance of “Do Right,” as it was often called, unveiled Lee’s unique soulful blues and swing sound in a key aligned with her speaking voice. Lee infused her rendition with a respectful nod to the style of African American singers of the time while delivering her own original stylistic interpretation. Any skeptics as to whether Lee had merely copied Billie Holiday’s sound were silenced after hearing Lee’s signature style develop over decades.

“Let’s Say a Prayer” was the final recording made while Lee was with the Goodman band. Recorded in July 1942 but not released until 1999, this patriotic wartime anthem was Lee’s swan song with the top swing band in America. Opening with a long instrumental section, Lee’s vocal chorus rendered heartfelt sentiments asking God to bless young men fighting for American freedom. She coupled this blessing with an exhortation to listeners to actively pray not only for “somebody’s boy” but also for the nation. Lee poured sincerity and precision into this song as she delivered its patriotic and spiritual message.

Unfortunately for this and many other outstanding swing bands, the American Federation of Musicians declared a recording ban to commence immediately after July 31, 1942. The ban continued for Columbia Records until 1944, eliminating further opportunities for more recordings to be made by union musicians. The union hoped that the strike would yield artist royalties from jukeboxes and radio stations playing music without paying for it. The strike backfired when no fair resolution was found to compensate musicians. Sadly, this unfortunate situation has continued to the present day. Modern songwriters continue to lobby Congress to rectify this long-unjust situation.

Interestingly, the ban did not extend over the contracts of singers, which was a major reason young Frank Sinatra’s career launched during this period. Singers were not required to join the union, so they could continue to record, albeit with non-union musicians. The monopoly that ensued for Sinatra upon his release of a slew of new recordings during the ban ensured that those recordings received radio play, since radio stations had nothing else new to play. Established union bands could not compete and many established singers, faithful to and standing by their union bands, waited for the ban to be lifted before returning to the recording studios. This reality gave Sinatra, an emerging non-union singer untethered by band loyalties, a greater advantage and career boost than that of any other singer in American pop music history. Although the Goodman band did not record during this time period, it continued to perform with Lee until she left the band in March 1943.

In addition to jump-starting Lee’s career and releasing several hit songs, the Lee-Goodman collaboration yielded another huge benefit for Peggy. In the summer of 1942, guitarist Dave Barbour joined the Goodman band and quickly became a new love interest for the chanteuse. In March 1943, having defied Goodman’s rule against band members becoming romantically involved with one another, Barbour and Lee left the band and soon married. Barbour became the first collaborative composer with whom Peggy wrote a long string of songs. For the moment, though, Peggy was content to simply enjoy being Mrs. Dave Barbour.