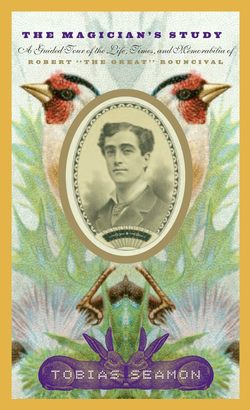

Читать книгу The Magician's Study - Tobias Seamon - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE Paper Vaquero

My word, look at the time. As usual, I have dawdled over the early part of Rouncival’s life. If I have been overlong with these details, my apologies. Perhaps for my own reasons, this period of Robert the Great’s life fascinates because it is so often overlooked, or at the least unexplored. Please leave your cups right there on the table, I shall take care of them later, and we will now enter the legendary period of Rouncival’s life. Please follow me across the study to the long wall, where Robert kept his most treasured possessions. I know, I know, to forsake the comforts of the Khan’s tent can be difficult, but nevertheless . . .

Young sir, please! Though it is dangerous only in its history, please do not spin that globe; it is a relic of Longwood, Napoleon’s manor of final exile on the island of St. Helena. Thank you, yes, I am relieved now. And you may have wondered about the tremendous number of books here in the study. As I told you before, Rouncival was notoriously lethargic regarding the written word. In fact, the volumes on these shelves are merely trompe l’oeil replicas. See, the library is hollow and the authors are entirely fictitious. As you may have heard, though, the wooden books are arranged in a deliberate order, and lexicographers, library scientists, even military code breakers, have studied the catalogue system in order to discover what, if any, secret the library contains. One gentleman, who if I may comment was in all aspects a madman, actually insisted the catalogue was a coded edition of one of the alchemist Maimonides’ lost or supposedly burned treatises. To this I say only: doubtful. It is far more typical of Robert to have created a façade of false knowledge. Deploying such a disposable, and easily ascertained, trick was a weakness of his. It should be noted that examinations of the hollow volumes did reveal a number of papers, from both Rouncival and Margaret Tillinghast. During various periods of the study, both used the empty library as a repository of their more precious, or secret, correspondences. As I am sure you all know, Margaret Tillinghast—sole heiress to the Wampum Flour Company fortune, jazz baby, and occasional participant in Rouncival’s escape artistries - was the woman who, in equal measures, contributed to the rise, then fall, of Rouncival’s fame. There will assuredly be more on Ms. Tillinghast later in the tour.

Okay! What you see before you is a papier-mâché skeleton of the sort most often seen during the Mexican festival of the Day of the Dead. The hat and vest signify that this particular skeleton is meant to be that of a cowboy, or vaquero, if you will. Similar to the circus poster, this is the lone object kept by Rouncival during his second stage of wanderings. Crushed by the death of William, Robert fled North America entirely in order to be alone with his sorrow and rage. This period of his life is perhaps the most mysterious of any portion, as Rouncival did not write to anyone, his parents included. What is known is that he used his final wages to book himself passage to the Caribbean and from there wandered the Latin American periphery. It is assumed that Rouncival used his conjuring skills to perform on the street and thus keep himself afloat but, again, very little is actually known. Rouncival kept the details of his sojourn a secret, saying only to a Chicago reporter one time, “It was a sordid land, filled with snarling, sordid people, and I was just another one of them, albeit with a limp and a very bad sunburn.” It was during this time that legend says that Rouncival apprenticed with a Haitian voodoo doctor and learned many of the black arts in a hut on a jungle mountaintop. Obviously, no one will ever know the truth of this, though his skills in magic afterwards did seem to take on an unprecedented depth, a depth not easily explained.

The one concrete fact of Robert’s days of exile is the meeting of his now almost equally famous personal assistant, Sherpa the Silent. Sherpa was in fact of Cuban heritage, a sailor and pirate of the Caribbean. Somewhere in his late twenties, he was really named Roberto Hernandez, and how he and Rouncival met was indeed sordid. Apparently, Robert found himself in a sinister confrontation in a waterfront tavern somewhere along the Yucatan coast, and for reasons unclear Hernandez used his own considerable knife skills to save Rouncival from a bloody death. Like the appearance of Jerzy the strongman earlier in life, Robert’s good luck continued so far as bar room saviors was concerned.

Following their victory, Robert and Hernandez became fast friends, exploring the seedier elements of the Mexican coast together. At one point they even penetrated the thick jungle in order to find a temple of Mayan origin, which Robert in that same Chicago interview would describe as “the perfect conglomeration of God and creeping rot.” As they traveled, they hit upon a scheme to further draw attention to Robert’s street-side magic acts, and they concocted a story of Hernandez being of Tibetan stock, a lost lama seeking to return to his home on the roof of the world. So Hernandez became the usually silent Sherpa, standing hawk-eyed and hawk-nosed at Rouncival’s right, hidden knife kept at the ready. When Sherpa did speak, he called the sandycomplexioned Rouncival Sahib, and did so with a gibbering accent again entirely concocted. No doubt, the two friends were laughing up their sleeves the whole time. Clothed in a wild amalgamation of gypsy, horse thief, and voodoo priest, they proved such a success in the plazas that Rouncival proposed they go to America to try their act there amidst the monied frenzy of the burgeoning Jazz Age. With little else to do aside from drinking, fighting, or pirating, Sherpa agreed readily.

They left during the festival of the Dead, and that is when Robert brought back the one souvenir of his days of sordidness. The paper skeleton was long a small aspect of his stage show, kept in the background as a kind of glum motif. The beautiful necklace around the neck and the arrows you see embedded in the ribs are later additions. Apparently, during a party in the study in the mid-1930s, Rouncival and the artist Frida Kahlo became so inebriated that they practiced their archery at the poor vaquero. The blood-red spot in the region of the heart is from her palette, and the hand-painted serpent beads were given to the vaquero directly from Kahlo’s own throat. For this alone, the dead vaquero has been valued as priceless despite being a rather cheap souvenir of its time. Fakir that he was, Rouncival would have enjoyed this estimation quite heartily.