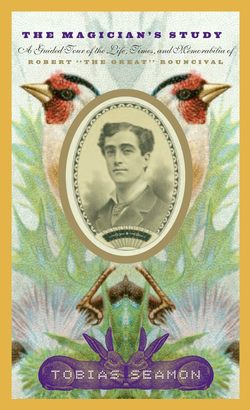

Читать книгу The Magician's Study - Tobias Seamon - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE Silver Stage

Ah, madam, I see the grimace has returned. Though it has been said I appear young for my age, I too am beginning to glance longingly towards the benches and small stage at the center of the study. Let us approximate Robert’s zig-zag path through life and head that way. If you all would be so good to excuse a momentary informality, I shall seat myself at the lip of the stage. So much better. Please rest on the benches and let us take just a second to ponder a typically overlooked aspect of Rouncival’s life. As we are already feeling strained from our standing and shuffling, imagine then how Rouncival must have suffered during his lengthy performances. The pains in his leg often made the act an ordeal. In fact, madam, and do excuse my referencing the lemons again, no insult is intended, Robert insisted that the juice of a citrus fruit relieved the pains in his joints. After more than one performance, he could be found in his dressing area, leg bared, with a cut-and-squeezed lemon perched atop his kneecap. Ha, I am glad to see the grimace has transformed to mirth. I too am tickled every time I consider Robert the Great greeting his admirers backstage with a lemon on his leg.

While we shall abstain from such measures, nevertheless, to be seated is a relief. That we are seated upon or in front of the first stage of Robert the Great’s career makes such relief that much more intriguing. In fact, these obviously charred boards and one-time stage for a Yiddish theater troupe are the true beginnings of Robert’s greatness.

Rouncival and Sherpa arrived in New York City by late October, 1921. With little funds saved from their wasted summer, they shared a room in a run-down hotel in the only neighborhood they could afford: the Bowery. Though perhaps not quite as fearsome as during its heyday at the turn of the century, the Bowery and the neighboring Tenderloin and Five Points districts remained slums of the worst sort. Prostitutes, cutthroats, thugs, thieves, cheats, sharps, pimps, addicts, gangs, the wanton, wicked, and unwanted all continued to make the Bowery their home. First-or second-generation immigrants were often thrown into this sinkhole of vice, and joining them out of necessity were Robert and Sherpa. That they did not become common criminals, petty pilferers, or die in a useless drunken orgy is testimony to Robert’s powerful will.

Their residence, if it could be called that, was named the Half-Shell Palace. Located along lower 6th Avenue in the nether region between the Bowery and the Tenderloin, the three-story Half-Shell had once been an oyster bar, with the owners living above. But when Robert and Sherpa entered the establishment seeking a cheap meal, they discovered that the Half-Shell Palace was actually a hotel, and one barely hovering above flophouse status at that. The owner of the Palace was a second-generation German Jew named Bill Silver, actual name Wilhelm Zylbar. A runner and general fixer for the Tammany political machine, Silver had worked in various, discreet roles for both Big and Little Tim Sullivan. With the death of Little Tim in 1913—he died, like Big Tim before him, a raving madman—Silver then did odd chores for the local bosses before deciding that he needed to retire from the faltering Tammany rackets. Silver purchased the unused Half-Shell in 1915, converted it into a hotel, and made a solid if not extravagant living by renting rooms to whoever staggered through the saloon-style doors. Any and all who stayed at the Half-Shell Palace remembered less than fondly the intensely cold lobby, where Silver and his Irish wife Maud sat huddled behind the oyster bar/check-in counter with a small coal stove warming their feet. Considering Rouncival’s career, walking into the Half-Shell seeking a dinner and finding instead Silver hunched behind the grungy hotel counter can be seen in hindsight as Fate furiously weaving her webs.

For you see, behind the hotel, a small carriage house was located amidst the tenements of the neighborhood. Attainable only by way of a dim alley alongside the hotel, the carriage house itself had been unused for years. Inspired, Silver purchased it along with the Half-Shell, blacked out the windows, built a rough stage and a small riser in the back, then installed some benches up front and opened a theater named, in mockery of the movies he so detested, the Silver Stage. There, at least once a week, a small company calling themselves the Minsk Troupe performed the great dramas of the Yiddish theater. It was upon those very benches, watching the passion plays of the Hebraic faith, that Robert underwent his final apprenticeship. It was also at the foot of the Silver Stage that he fell in love for the first time, with none other than the cat-eyed chanteuse of the company, Roza Ellstein.

If you would, permit me a moment to set the stage. The conjunction of personalities, heritage, and aspirations alone is remarkable, though perhaps not atypical of the Bowery of the early 1920s. All roads met at the Half-Shell Palace that winter. We have Silver, former cog of the Tammany machine, with his shanty-Irish wife Maud, a morose, mostly silent personality who possessed a savant-like ability to replay any tune on the piano. Strange Maud often assisted the Minsk Troupe with their musical numbers, while Silver, despite owning an establishment named for shellfish, remained faithful to his Hebraic roots by allowing an amateur theater company to perform Yiddish dramas in his carriage house auditorium. Then we have young Robert and Sherpa, two roustabouts essentially at loose ends, performing in the street again for pennies, kept above a truly criminal existence only by Robert’s burning, yet still confused, desires to become an artificer of real worth. Then add the Minsk Troupe to the tableau, led by a talentless writer and producer named Jacob Davidoff who happened to luck into one of the premier talents of her time, Miss Roza Ellstein.

A Jewess of German-Polish lineage, Ellstein possessed a rapturous alto voice and multi-colored eyes; her right iris was a lush green while the left was a far lighter, pale amber hue. To have seen Miss Ellstein, one week a dark and vengeful Lilith, the next a tormented victim of a savage dybbuk (a kind of ghostly, ghastly demon in Jewish folklore), only to return the following performance as Judith carrying the severed head of Holofernes, was to have witnessed a marvel. Just approaching her twentieth year and close to six feet tall, with mahogany hair and a voluptuous figure, it is no wonder Roza Ellstein alone rose above the Minsk company, becoming by 1923 a lead player with the legendary Folksbeine Troupe. That Rouncival, Sherpa, and Ellstein— names of notoriety all—could all three come together if only briefly at such a distinct place and time proves: the distance from half-shell flophouse to the greater, silver stages of the world may be only a short stroll down a dank alley. Such is, or was, America.

I have rhapsodized enough. Let us return to the story, which was by the holiday season of 1921 very cold. Unused to such weather, Sherpa was extremely hard-pressed by the chill, and he took to wearing all of his costumes at once just to keep warm. With the robes, kaftans, headdresses, and whatever other flimflam Robert told him to wear, he must have truly begun to look the part of a beleaguered Tibetan mountaineer. In fact, their act was hardly supporting them, and Robert took for a while (though he denied it later) to working what we would now recognize as an early form of a shell game. Never an obvious aspect of the con, Sherpa would lurk around, carefully observing Robert’s gulls. At any hint of violence or wrath on their part, he would leap in pretending to be yet another victim of Rouncival’s scams. With much clattering and shouting, Robert would allow himself to be chased down the street and around the corner by the maniacal, knife-wielding Sherpa. As an escape method, it was highly effective, but it also meant the two were forced to go further and further afield into bitter weather lest any previous witnesses see a repeat performance.

All in all, they were often down to their last nickel and took to spending their time in the lobby of the Palace, chatting with Silver and assisting him with whatever sots fell through the saloon doors seeking “berths,” as Silver wryly referred to his beds. “The sooner we get them into their berths, the sooner they stop screaming” was the old man’s mantra. The veteran of many a Bowery donnybrook, Silver enjoyed the young charlatans, realizing quickly they were relatively harmless, and he would often regale them with stories of the old neighborhood and its horrors. He relished telling of McGurk’s Suicide Hall, where patrons took to tossing back carbolic acid in order to end their earthly misery; the Haymarket Dance Hall, so popular during its glory that the owner dared to charge an unheard-of-before admission price and actually got rich doing so, and Honest John Kelly’s, a 24-hour gambling den whose Stygian doorman was nicknamed Dandy Jack. These stories entranced Rouncival, and Suicide Hall especially would become a notable aspect of his later, mystery performances. Still, a good story could only be so warming, and it was during a particularly freezing evening that Silver suggested the two young men attend a show by the Minsk Troupe, if only for the wealth of warm bodies in the carriage house.

While Robert had shown little interest in the comings-and-goings of the troupe, and he certainly did not have even a smattering of Yiddish, the night was so chilly that he and Sherpa pounced at Silver’s suggestion. I have here Robert’s description of first seeing Roza Ellstein as she performed in Davidoff ’s paltry revision of “The Golem.” The description actually comes from a rare speech given by Robert himself to a meeting of the Harbingers’ Club held right here in the study. And yes, madam, your smirk has given you away. Rest assured, there will be far more regarding the infamous Harbingers’ Club before the tour is over. For now, let us content ourselves with Robert’s entranced memory of that night, transcribed by the secretary of the club and later approved by Rouncival as an addendum to the official minutes, all of which were found within the hollow volumes.

My god, it was cold that night. The water bucket in our room had frozen over, and even standing down in the lobby with crazy Maud and the stove wasn’t much help. Silver had gone out to find anyone passed out in the vicinity, as they certainly would not have survived the night. I was leaning on the counter, hoping against hope Maud would make some tea to take the chill off, while Sherpa just stood around by the stairs at the far end of the check-in, moaning and shivering beneath his bundles of rags. All I could see was his sharp, red nose sticking out from between the scarves.

Finally Silver reappeared, banging his way through those goddamn saloon doors, stamping and clapping his hands. He hardly gave Sherpa or me a glance as he darted behind the counter and then, so help me god, pulled down his pants in order to warm his bum by the stove. He stood so close I thought for a moment he was going to come to terrible harm but he seemed to know what he was about. As his behind heated, so did his ability to speak, and he and Maud began to get into their usual argument, though it was Silver that did all the shouting, about her cat.

You see, Maud had this old cat, a fat black thing she called Bear who she would set on the counter every now and then as if producing a magical treasure. Bear was pretty old and mostly slept next to the stove, winter or summer, all day and night long. But when he was on display, oh, how that kitty enjoyed it, and he had the oddest habit of ramming people with his head. It was Bear’s way of saying hello and we all liked him well enough, but not the way Maud did. Every time she hefted that beast onto the counter, she would nod with absolute pride, “Bear comes from the Old World.” This never failed to set Silver off. He would pound his fist, shout, holler, and generally make an ass of himself (which as you know he was hardly ashamed of in the first place), insisting that Maud stop lying about her cat. “ You know good and well that cat is not from the Old World. Staten Island, maybe! Blarney County or wherever your people come from? No no no, that is impossible!” This hardly fazed Maud, who would just repeat stubbornly, “Bear comes from the Old World,” with old Bear all the while lowering his head and bonking everyone in sight just to punctuate her point. Ah, but it was a gas to witness.

That night, however, it was too cold even to enjoy the usual display, and I think Bear just wanted to return to his nest by the stove. After Silver had settled himself down and gotten his behind pretty well roasted, he pulled his pants back up, gave Sherpa and me a squint, and said, “You fellows are making me cold again just looking at you. What, have all the bars in the Bowery closed for the winter?” Sherpa was shivering too hard to answer, while I just glared at the saloon doors and made a face. Silver didn’t care, giving his usual excuse: “This is America, land of the cowboy, land of the free.” I wanted to lasso him and tie him to a train track at that moment, but then Silver suddenly slapped the counter and said, “I know what you boys should do! The Minsk is playing at the carriage house tonight. It’s a good one too, ‘The Golem.’ If that schmuck Davidoff doesn’t ruin it, that is. Come along.”

Sherpa and I barely budged. The poor Cubano was frozen to the stair railing, I think, while I hardly wanted to see a play in a foreign language in some horse barn down at the end of a rat-infested alley. Silver had put his coat and ridiculous Russian hat back on and looked like a bear himself, but he was halfway to the doors before he noticed neither of us were following him. He turned, whistled, and said again, “Come along. It will be warm. What else can anyone do in this cold?” Neither of us was convinced, and with a sigh, Silver surrendered and said the one thing that was guaranteed to rouse us: “There will be women there. Actresses. A good Jewess may be a good Jewess, but an actress is an actress also. I’ll introduce you afterwards.”

We were halfway down the alley, booting rats out of the way and pulling our hats lower, as Silver explained the play. “A golem is like a puppet, a puppet without strings but with the name of god under its tongue. Golems used to be created all the time by wizards too lazy to do chores, too poor to afford help, or too ugly to find a wife. Good to be a wizard, eh? Maybe that damned cat is a golem? More like a wizard he is. Hmmmm.”

As Silver pondered the kabalistic secrets of Bear, we reached the end of the alley, where it opened into a small, cobblestoned square of sorts. The tenements blocked the whole area off, and the way they loomed above, a few lit windows, mostly dark ones, a few voices or cries falling down upon us, it felt as if we were at the very bottom of the world. We could hear the crowd chattering inside the carriage house, the usual buzz of neighbors meeting, greeting, and gossiping, while a lank man all in black stood huddled inside the doorway. Silver bustled all of us inside—“These are my friends, Adler, no charge. Good man, good man”—and like everyone else, we shuffled towards the big wood stove along the back wall. I wondered if Silver would bare his ass again, but he was too busy chatting up everyone to bother. It seemed so familiar, yet so different, to be in the playhouse. I felt the old rush of the Extravaganza surging in my veins, but with the foreign tongues and accents and clothes, it felt also so wonderfully alien. Also, so wonder fully warm. Sherpa was just beginning to unwind himself from his layers, and I could still hear Silver bemoaning Maud’s lunacy, when the lamps were dimmed and the curtain rose. I expected to see some kind of evil sorcerer lazing about a castle chamber or maybe his puppet monster, but instead, I saw Roza Ellstein for the first time. She was dusting a mantle. As she dusted, she sang to an accompanying violin from behind the backdrop, and I have never heard such a voice before or since. The richness, the quiet joy (she was obviously playing some kind of contented wife), everything seemed not so much a song of the voice but a sound emanating from her whole body. I could have sworn her fingers themselves let loose in song as she dusted. I couldn’t comprehend a single syllable, but I understood everything. Or thought I did, until she turned and faced the audience. It was then that her two amber-then-green eyes played across all of us. I could feel Sherpa stiffen next to me, and I knew, knew, I was truly at the bottom of the world, and above the earth itself was the woman on stage, seeing all in multiple hues as she dusted a mantle piece with singing fingers.

I hardly remember the rest of the performance or the other performers either. There was of course the monster, played later I found out by Davidoff, and performed so stiffly and horribly it almost made for a good effect. I didn’t then know the real play, and whatever inventions or distortions the writer had made were beyond me. Silver would often hiss at one of Davidoff’s grosser translations, “Idiot! The man is an idiot,” but I didn’t care. How could I? I stared at the housewife, at her eyes, and I could tell once and once only she met me with her own eyes and knew I was a stranger to the carriage house, to her world. Of course, there was no blinding flash, at least for her at the moment, and she stayed in character, but I knew. The benches were filled that night, but I stood, I stood for the entire performance, and it was only when the curtain fell, blocking the wife from my sight, that I felt my leg about to buckle. I grabbed poor Silver’s shoulder pretty hard as I struggled to remain standing and applaud at the same time, then I fairly shouted in his ear, “You must introduce us. You must.” He smiled, nodded, then looked up and saw my expression, and his whole demeanor shifted, becoming very intent and businesslike. Silver understood it was a matter of seriousness, of matchmaking, even, and told me quietly with a pat on the hand, “Of course. But first, please stop breaking my arm.”

Ah-hah, and thank you: I too have felt like applauding at the conclusion of Robert’s account. Though Robert, in his later years, may well have been waxing eloquent to the Harbingers’ Club, that he stood for the entire performance was nigh on a feat. H. Leivick’s “The Golem,” first published in 1921, ran upwards of four hours! Of course, especially considering Rouncival’s description of the opening scene, which differs completely from Leivick’s poetic script, the golem he witnessed may very well have been the creation of another, now entirely forgotten author. The production could also have been simply, as Silver seemed to believe, the victim of Davidoff’s incompetent direction. For the sake of our own sanity, let us drop any such conjectures and know only that, yes, Robert was instantly enchanted by Roza Ellstein, and enchanted to such an extent that he collapsed when the curtain finally separated him from the wife on stage.