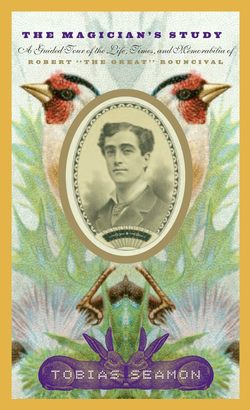

Читать книгу The Magician's Study - Tobias Seamon - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE Traveling Extravaganza

Please, come forward, come forward. And would the last person through please shut the study doors? They, if anything, are safe to touch. My gratitude, young sir. Now, I understand that at first impression the study is hardly what anyone could expect. It should be said that the room was designed originally as an atrium, and thus the various tall windows and the high glass ceiling. It was during the early 1930s, when Rouncival permanently retired to this estate, that he converted the atrium into the shelf-lined study that is currently awing you. More on the construction of the study later, however. For now, let us look to the niche on your left, there along the short wall, containing the circus poster.

As I was saying, Rouncival grew up a child of the inside light, sitting at his father’s elbow and brooding on his various abuses. As a student, he showed a clear aptitude for mathematics and the sciences, while history and most of literature bored him to tears. Even as an adult, Rouncival read only as a matter of necessity, though he did take clear pleasure from the murderous conundrums offered by Misses Christie and Sayers. It was during such a period of dissatisfied quietude that Robert did as many alienated youth have only dreamed of doing: in early 1914, he fled home and joined the circus.

Before you imagine sequined acrobats, glamorous tents, tamed lions or mighty elephants, please know that this particular show hardly merited the title of “circus.” Rather, it was a motley collection of aged and mangy animals, arthritic contortionists, not-so-strong men, and gimcrack tinkers. As you can see, the poster is shoddy print work indeed—whether that is a tiger in the upper right corner or merely a very strange goat has always baffled me—but it is the sole artifact Rouncival brought away from his years on the road. The show was called “Welt’s Traveling Extravaganza,” with the carnival run by a genial huckster named Barnabas Welt. A former clown of Vaudeville himself, Welt had a deep sympathy for circus folk, no matter how over-the-hill they may have been, and his circus was a veritable refuge for those that couldn’t or wouldn’t give up the life. It was fortunate for Rouncival that Welt was such a person, for who else would have taken on a lamed, spindly, penniless youth as a gofer and all-around assistant? Rouncival would always claim that Barnabas Welt was the kindest man he ever met, though this was said at times with a borderline sneer.

Thus, as the lamps of Europe were doused and the old world was murdered beneath the mud of Flanders, Robert Rouncival tramped the mill towns, logging camps, and farming communities of upstate New York and New England. From Blue Mountain in the Adirondacks to the rubbish-strewn lots of Worcester, Massachusetts to the hardscrabble hollows of Vermont, Robert acted as Welt’s advance man. Limping into small villages and towns, he told everyone which rented-for-the-weekend field or empty warehouse the Extravaganza could be found at. It was probably during this time that Rouncival also acquired his taste for drink, as Welt, an abstainer, insisted that Robert tack a poster in every crossroad tavern or factory gin mill along the way. So Rouncival began to grow into a man, and a hard man at that, learning everything he could from the sad, faltering tricks of a dilapidated circus, its run-down folk, and its often impoverished audiences. And as he did so, he wrote to his brother William in the war.