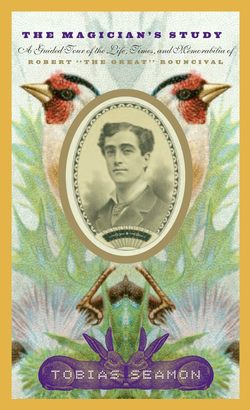

Читать книгу The Magician's Study - Tobias Seamon - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Top Hat ON THE Doorknob

While we are not yet ready ourselves to leave the Silver Stage behind, please allow me to retrieve a prop before I continue with Robert and Roza’s soon-to-blossom romance. You no doubt have noticed the top hat hanging from the closet handle here. The closet actually contains many of Sherpa’s later, magnificent costumes. Though some are quite extraordinary, we simply don’t have the time now to display them.

So, you see, an ordinary top hat, often worn by amateur magicians at children’s parties, small fairs, and so on. And yes, young sir, it is very much a laughing matter, whether perched on my head or crowning another’s. Rouncival felt the same way, despising it and the ubiquitous wand so many of his fellow artificers displayed on stage. Robert never actually wore this hat except in jest, but it was very much a part of his life. First, it served as the catch for whatever coins were thrown his way during the street performances, and second, whenever Robert or Sherpa was occupied with a young lady in their room at the Half-Shell, the top hat was hung on the outer doorknob so the other would know to leave the berth undisturbed. Perhaps the effect was magical-unto-mundane, but as a signal the top hat did the trick. Indeed, it became a running joke between the friends that to have a liaison with a young miss was to “pull the rabbit from the hat.”

While they certainly had had their share of sexual experiences, it must be said that both Rouncival and Sherpa were at that time far more used to affairs with, how shall I say it, women of low birth. Pulling the rabbit from the hat more often than not involved a dance hall gin bout or even perhaps an exchange of coin. This makes them distinctive in neither their time nor their age group, but it does make Robert’s desire to court Roza Ellstein an entirely new ball game, so to speak. Though she too was of middling-to-impoverished origins, and was as I mentioned even younger that the two rascals lurking at the Palace check-in, nevertheless she was most definitely a woman of far higher caliber than Robert had ever dared pursue before. That she was a Jewess, and often shadowed by the equally smitten Davidoff, did not help matters. It would have been extremely easy for Rouncival to abandon his hopes, especially considering the repugnance he felt for his twisted left limb, but something had changed within Robert. Whether it was Ellstein’s enchantments or a newfound realization that he could stand for any amount of time given the proper circumstances (or illusion), Robert’s desire to become a magician of fame and to have Roza combined into a single goal, a goal that he pursued with previously unseen diligence.

True to his word, Silver introduced Rouncival to Ellstein following the show, and Rouncival apparently rose to the occasion, making quite a good impression upon Roza. He also stated later that he more than embellished his role with the Traveling Extravaganza, claiming that he was the carnival’s magician and not its gofer. As one would know from the legend of the golem, perhaps putting the correct word under the tongue is all that’s needed to animate. By proclaiming himself a true artificer, Rouncival may well have become one at that moment, and directly in front of Ellstein’s lovely multi-colored eyes to boot. As a brief aside, Robert would later say that was why he billed himself as “The Great”: “If I say I am great, the audience, catcalls at hand, will probably hope to see that I am not, but the mere suggestion makes actual greatness possible. That is why no performer, ever, has dubbed themselves ‘The Adequate.’ ”

With a combination of wheedling, boasting, and Silver’s bemused compliance, Robert managed to get himself insinuated at the carriage house as a magic act. He and Sherpa began to open for the Minsk Troupe as a warm-up. While Davidoff, a sour personality at best, wasn’t especially pleased to see any more of Robert’s presence—he had taken to attending every one of the company productions, sitting front and center and no doubt gazing non-stop at the also bemused, yet charmed, Ellstein—Robert’s sheer pluck was a hit with the audience. The weekly gate at the carriage house doubled as more and more came to see the fresh-faced conjuror and his silent, supposedly Tibetan assistant. That his act, with the dead vaquero brought down from the berth to the stage, was so seemingly at odds with the typically moralistic dramas of the Yiddish theater only seemed to enhance each show’s effect. Rouncival, in love with his own, newly invented abilities, became a magician of startling confidence. He told shaggy dog stories, teased and taunted the audience, and loosed his illusions so casually that by the time the audience realized he had transformed a chair into a burning candle, they’d explode into applause even as the candle floated away into the rafters. One of his running gags was that he was scared witless of Sherpa, pointing at the dead vaquero with a shaking finger as though that had been the last man to cross the sinister Tibetan. Certainly he had more than a few flubs—his early attempts at ventriloquism failed badly, though later he would master that art to a terrifying degree—but his will was strong. If a joke or an illusion flopped, Robert would ignore the stillness and toss off yet another one-liner to break the silence. All in all, his youth, Welt-ian flourishes, fiendish energy, and simple ability to make objects disappear astonished the audience nightly. It should also be noted that Sherpa’s previous experience constructing pirate hideaways was an invaluable help; by the time Sherpa had completed his adjustments to the stage, Rouncival would smirk, Hannibal’s army of elephants could have been hidden beneath there.

Such were matters as winter progressed and the New Year, 1922, was rung in. Robert began to perform on his own one night a week on Saturdays, and while Silver took half of every show’s gate, still, Rouncival and Sherpa had at least a bit of pocket money. Soon, it was Ellstein, escaping from the Sabbath dinner at her aunt’s house, who could be seen seated on the front bench as Robert performed his routines. It was obvious to all that a romance was budding.

But then, in February, Rouncival received word that his father had died. It was Silver who handed Robert the telegram and Silver also who watched the silent Rouncival slowly limp up the Palace stairs seeking his berth. The top hat was placed on the doorknob, and for two days Robert remained in his berth, alone. Though Sherpa knocked, Rouncival never answered. Finally, Robert emerged. He came down the stairs as slowly as he had mounted them, took Silver’s arm, and said, “I need help. I want to sell my father’s house. Now.” Silver tried to intervene, pleading with Rouncival not to rid himself of the inheritance, but it was to no avail. Rouncival was determined to have nothing to do with his past. Stating his categorical objection to the entire matter, Silver then brought Rouncival to a shyster attorney, who had the place sold well under market value within two weeks. At the signing, Silver could only sigh with resignation, “Well, I suppose every young man must piss away at least one inheritance in his lifetime.” Determined indeed to flush his new assets away, that night Robert took Sherpa, Silver, Ellstein, and Davidoff out for a night on the Bowery. The intention was to paint the town red, and by the end of the evening, Ellstein found herself in Rouncival’s arms. Here, taken also from his lecture to the Harbingers’ Club, is Robert’s account of that wild night.

Before I begin, I would like to add that now is perhaps an appropriate time for the young gentleman to take a moment to wash his hands. Rouncival’s account contains some explicit descriptions of his liaison with Ellstein. The young sir will stay? Ah, but it is good to see parents unafraid to allow their children at least a brief glimpse into the pleasures of the adult world. I am sure the young master will also, by the end of Robert’s account, be a fervent admirer of Roza Ellstein.

What can I say of that evening? My father dead, my home sold, a roll of bills in my pocket, dressed in a new black shirt, collar, and coat, that beastly watch ticking solemnly next to my heart as we gathered in the lobby of the Half-Shell. Silver demanded that I give him at least half the money roll for safekeeping, but I’d have none of it. Sherpa too was duded up, though where he’d gone to purchase that crimson silk shirt was beyond me. He’d trimmed his moustache and beard down into an empire, and for the first time since the Yucatan he truly looked the swashbuckler. Silver, a dowd as always, wore black in honor of my father, though he brandished a wonderful hip flask before we went to fetch Roza. He displayed the inscription, “Bill Silver, for 20 Years of Valued Service, ‘Little’ Tim Sullivan,” and we all sipped, in memory of Tammany’s greatness and my father the watch repairman. Then we went out into the Bowery.

It was a short stroll up 6th Avenue to Roza’s aunt’s house. It was late February, starting to become dark, though an unseasonable thaw had enmeshed the city, and everyone was out on the streets, breathing air that didn’t ice the lungs for the first time in months. Roza too was on her stoop, wearing a long fawn overcoat I’d never seen her wear before and shadowed as always by that fool Davidoff. The cashmere hung beautifully on her tall frame, and with those eyes, my god those eyes, gazing carefully at me from beneath what looked also like a new cloche hat, I could barely stand to look at her. I thought my chest would implode. I shook Davidoff’s hand, a fishy grip if ever one existed, then inhaled deeply as Roza embraced me, whispering, “I am so sorry, Rober t . . .” She smelled of violets or some such flower, she smelled like spring. Then she looked at me closely, holding me a moment at arm’s length, and smiled. “Whiskey?” she asked, for let us not forget that Prohibition was nominally in place. Caught out as we were, I could only grin. With a charm I’d hardly ever seen him display, Silver reproduced the flask with a bow, and Roza and Davidoff also imbibed, both uttering a Hebrew toast, perhaps prayer for the dead, as they did so. With a wave to Roza’s aunt lurking in an upstairs window, we were off.

If you’ve ever been on a carnival thrill ride at Coney Island or some such place, you will then know how that evening felt. Everything a blur, everything in motion, shouts, screams, open mouths, then the occasional stillness that has such import it becomes burned into the memory from amidst the maelstrom. Such was that night. Miracles, marvels, and many other things besides as we celebrated my newfound fortune. Down 6th Avenue we went, and down into some foreign, almost infernal, world we descended. I wish I could relate more of the night, but with so much a haze, again, it is only the marvels that stand out.

It began at Duffy’s Point, perhaps the most decent establishment we would venture into the entire night. Silver passed the flask, glasses were raised, and the minstrels, a bunch of Irish waifs, struck the first chords. From there, already with a gaggle of drunken followers, we went to the Paladin, where Davidoff’s impatience for drinks made the barkeep so irate that he flicked beer foam into Davidoff’s shocked face. From there to the Gas-house where a man referred to Sherpa as a nigger and had his nose broken for his efforts while Sherpa somehow didn’t even get a speck of blood or gristle on his shirt. On for a quick sup at a chinaman’s chophouse before reaching the underground gin mill the Copper Penny, where a scaly eye peered at us through the peep-hole. It was only at the Penny that we paused, Silver taking Roza’s arm quickly as he solemnly informed her, “This is not a place for ladies.” Roza laughed and such a laugh it was, head thrown back with the deepness from her strong throat, those green and amber eyes flashing. “Since when has an actress been considered a lady?” she smirked, grabbing the flask from his coat. Drinking heartily, Roza pounded the door directly beneath the watch-man’s eye and all together we reeled inside.

The Penny was bedlam, and we were yet another group of inmates taking charge of the asylum. The throngs pressed back and forth from the bar to the dance floor, and Sherpa’s beautiful crimson shirt the only way of maintaining a bearing as we waded in. Somehow Silver found us a snug near the back (the man had a talent, a genius in fact, for such things) and we piled in, Roza positively hot against my shoulder as she stripped off the cashmere and reached for glasses. Toasts, more toasts, more toasts again, and Sherpa in red was on the dance floor, stepping lightly from one bird to another as his fancy dictated, a small, reeking cigar burning continuously from the corner of his mouth. Silver, like always, had discovered an acquaintance from his Tammany days and was plotting the downfall of the reformers who’d taken over City Hall. Roza in the heat took off her hat and let her dark, dark hair hang loose. With a cry, she too was out on the dance floor, next to Sherpa, and together, well, together they burned the dance floor down. Even amidst the uncouth floods, space cleared for them to cut the rug. God knows what those steps actually were, and I, with my leg and all, hardly knew whether they were doing the Turkey Trot, the Collegiate Shag, or the Charleston, thankfully a craze just then in its infancy. I must admit, for a time I felt a pitiable, self-pitying envy for Sherpa, understanding for the first time Davidoff’s equally pitiable predicament. He was almost comatose from all the drink, and though I felt nothing but scorn at the time, he could hardly be blamed for falling out. Remember: accustomed more to the frolics of coffee house malingerers, he was hardly in his element with a former carnie, a Latino pirate, and a hardened Tammany man. Even now I can hardly think of a group better suited to heavy indulgence. Still, I too was a bit worse for the wear at the moment, and let my sodden mind wander for a time. Then coming back up, I saw Roza and Sherpa standing in front of the table. My expression must have given me away, for Roza turned and laughed to Sherpa, “Oh, look at Robert—he’s jealous.” Admirably on his part, Sherpa gave a look of concern, though if it was for my feelings or because of worry that my often-terrible temper was going to explode was difficult to tell. Then Roza did as no other woman had done before, or since: she grabbed my hand, began lifting me from the snug (“Oh, come on, Robert!”) and brought me out onto the dance floor.

I hardly knew what to do with myself. Inebriated or not, I felt as though my face was on fire from blushing. Roza held both my hands as we waited for the band, a quintet of blacks led by a chubby pianist named Kid Memphis, to start up again. Fortunately for me, they broke not into one of those flapping, shaking frenzies, but into a slow, tinkling ragtime tune. Roza threw her head back again at the sound, delighting in the maudlin piano, and pulled me close. Her fingers ran along my neck, tugging sometimes lightly at my hair, and I held onto her. Again, it was as though her very fingers were singing, singing this time directly to me, the ragtime rolls spinning up and down my spine. I was transfigured, and transformed, by Roza, by Kid Memphis, by the whiskey and the heat and the money roll and the other couples clutching each other within the Copper Penny, and for the one time in my life I felt as though I had become water. My leg, always so gnarled and gripped and tripping on itself, loosened, becoming water itself, and with it my hips and my hands as well as I pulled Roza closer, even daring to kiss her neck. She did not resist that or my hands now at hers hips tightly, but sighed and shook her hair back so I could kiss even more of her throat as the ragtime piano rolled on and on, and we rolled with it.

After that, all became a wash again. Somehow or another, we returned to the snug, hauled Davidoff to his feet, and were out of the Penny, into the Bowery and back to the Half-Shell, Roza and I arm in arm the whole walk. Barreling through the saloon doors and seeing Maud at the counter, I wondered if Silver was going to be in for it. But Maud said a nary a word, instead disappearing to the back to fetch huge mugs of tea with lemon and a plate of soda bread made just that evening. Chairs were scrounged from various empty berths, and all together we sat, sipping and sobering and smacking our lips at the delicious bread and strawberry preserves. Old Bear came out for the party as well, bonking each of us in turn with his fat black head, and Silver didn’t even dispute the cat’s Old World origins. Instead, he just yawned and muttered over and over, “What a night, what a night. Not since Pay-or-Play came in at 100 -1 has the Bowery seen such a night . . .” I myself couldn’t take my eyes off Roza, and my every glance was met with an equal glance. Seeing Davidoff slumped and passed out in his own chair, she rose. I thought for a terrible second that she was going to awaken the schlub so he could escort her back to her aunt’s house. Instead, she removed her long overcoat and, with cruel finality, gently covered him with the cashmere. Ever a gentleman, Silver kept his eyes discreetly pinned to his lap as Roza and I ascended the stairs to my berth. Before I shut the door, the top hat was carefully placed on the knob.

The next day, I could hardly contain myself. I escorted Roza— even lovelier in her dawn disarray—to her aunt’s, then fairly raced back to the Half-Shell to boast of my conquest. Enchanted, I had been spared the worst of the binge’s aftereffects, but neither Silver nor Sherpa was so fortunate. I found them hunched over in the lobby chairs, moaning, holding their heads, and slurping tea again. Unmerciful, I talked a mile a minute, regaling their aching ears with my exploits.

“You should have seen her! God almighty, but she has the appetite of a man. She asked about the top hat, I made up some dumb excuse, but she brushed my lies aside. ‘You’re quite the Casanova,’ she teased, toying with my shirt as I toyed with the buttons of her cream dress. We were standing near the bed, and then, the dam finally broke. We were on the bed, kissing and kissing and kissing, our clothes getting caught on elbows or ankles, and we began to laugh at our own spectacle. I wondered how she would react to my twisted knee and the grotesque bone, and for a moment I tried to keep it concealed beneath the sheet, but she murmured something I couldn’t understand and caressed it all the more, kissing me all over. She climbed atop me, so light and so long-bodied all at once. As I ran my hands over her, I realized with a squawk that she had shaved her pussy! It was almost too much, and she giggled at her own impudence or at my own astonished, excited reaction or both. Then, by god, then we had at it. ‘C’mon, Robert, make me disappear,’ she teased again as she mounted me, directing my hands and fingers wherever she wished. Gentlemen, we went on for hours, hours, and that is the truth. Can you imagine, a shaved cat! Until you’ve experienced that . . .”

Too hungover to appreciate the greatness of the night, Silver and Sherpa just gave sickly smiles and rubbed their bloodshot eyes. Then Sherpa asked if the top hat was still on the door, he really wanted to sleep in his own bed; for reasons he couldn’t dope out he’d gone to sleep underneath the stage of the carriage house. Such, I suppose, was love in the Bowery.

And such it was. Though Robert, in relating the details of that night yet again to the Harbingers’ Club, reveals himself still as somewhat of a braggart, nevertheless, he was undoubtedly in love with Roza. Ellstein and Rouncival were inseparable all during the spring of 1922, taking the new train line to Coney Island, picnicking in Central Park, and generally behaving like lovers in New York City have always done. Though she continued to live with her aunt, Ellstein could be found more and more at the Half-Shell, enjoying time with Robert before and after their mutual performances. Both were gaining fame as crowds flocked to the Bowery to see the amazing young magician and chanteuse hidden at the Silver Stage. As word of their talents spread, so too did their audiences. Scouts for other Yiddish theater troupes congregated at the front benches, while impresarios with open dates at their entertainment halls sought out Rouncival. Along with those having a professional interest in Robert and Roza, others came merely for the spectacle. Among them, in June of that year, was the jazz baby heiress Margaret Tillinghast, and her arrival at the Silver Stage would change everything. No one, not even Ellstein or Sherpa, would have as pronounced an effect on Rouncival’s career as the willowy, monied Tillinghast. Some claim she altered Rouncival’s path in ways most unbeneficial, while others insist she is due much of the credit for his legend. While we can decide ourselves upon the effect of Tillinghast’s entrance in Robert’s life, let us, just for a moment, hold the image of Rouncival and Ellstein together, honeymooners surrounded by Sherpa and Silver and Maud and the hapless Davidoff even, a family of sorts formed within, and because of, the Bowery, drinking tea in the lobby of the Half-Shell Palace, a top hat on the doorknob or perhaps a black cat from the Old World brought out for special occasions. As Rouncival himself said, “Ah, but it was a gas to witness.”