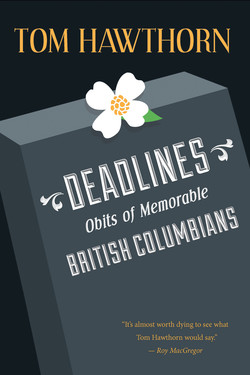

Читать книгу Deadlines - Tom Hawthorn - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHarvey Lowe

World Yo-Yo Champion

(October 30, 1918—March 11, 2009)

Little Harvey Lowe’s mastery of a simple, ordinary toy—the yo-yo—became his passport to a boyhood adventure that would make him a world champion. He wore proudly for the rest of his days a title won at age thirteen.

In his nimble hands, the yo-yo became more than a child’s plaything.

He handled the string like a puppet master, causing his yo-yo to spin, dance, and, in the nomenclature of the pastime, sleep. He claimed a repertoire of a thousand tricks. On rare occasion, he performed a feat in which a pair of wooden yo-yos whipped within a blink of his face. He called this the death-defying Mandarin puzzle, a reminder of the toy’s origins as a hunting weapon in the Philippines.

As an adult, Lowe appeared on stage at clubs as one of the entertainments in an era when a venue’s nightly attractions might include a half-dozen acts. He later appeared on television, most notably on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, for which he wore an elaborate robe in his role as a Confucius Yomaster. It was his job to teach the venerable art to a character portrayed by Tommy Smothers called Yo-Yo Man.

Away from the stage and screen, Lowe acted as an unofficial ambassador to Vancouver’s Chinatown, with all its attendant mysteries. It once fell to him, for instance, to educate the actress Julie Christie in the proper technique for smoking opium.

Earlier, he had become the first Chinese-Canadian to host a radio show.

Willing to indulge ballyhoo to promote his craft, Lowe professed a belief in the spiritual depth of playing with a toy on a string. “There is a definite Zen spirit to the yo-yo,” he once told newspaper columnist Denny Boyd. “It’s just wood and string and it occupies a tiny space in your hand. When you release it, you free its spirit and create vibrations that come back to you.”

Named Lowe Kwong Yoi at his birth in Victoria in 1918, just twelve days before the end of the Great War, he was the youngest of ten children born to Lowe Gee Quai, born in China, and Seto Ming Yook, born in Victoria. His father, known as Charlie Lowe, was one of three brothers to establish tailor shops on Government Street in Victoria. The boy was raised in a household overseen by his biological mother, but the woman who most looked after him was his father’s concubine, he told reporter John Mackie. “Imagine, both of them were living under the same roof. But they got along good,” he said.

At twelve, he bought his first yo-yo for thirty-five cents. He soon mastered the novelty, the popularity of which was promoted by neighbourhood contests. Young Harvey won these, graduating to showdowns at department stores. Continued success led to invitations to compete in Vancouver, where he again defeated all comers. Irving Cook, a promoter, took the boy overseas as a yo-yo craze swept Britain in 1932.

A yo-yo demonstration performed at the Derby Ball at Grosvenor House in London on June 1 was witnessed by the American aviatrix Amelia Earhart and by the Prince of Wales, heir to the throne. The prince even tried his hand at the toy.

At the Empire Theatre on London’s Leicester Square, Harvey Lowe faced a dozen young challengers representing rival yo-yo manufacturers in a showdown demanding skill, innovation and, as it turned out, a bit of luck.

Lowe was one of three competitors from Canada sponsored by the Cheerio company, which was promoting its No. 99 yo-yo. The other two, both from Regina, were Gene Mauk and Joe Young, the reigning world champion. In the finals, Young’s string snapped, while Lowe was able to complete his performance without mishap. He was crowned world champion a month before his fourteenth birthday. With the crown came £1,500.

Though born in Canada to a Canadian-born mother, Lowe was said to represent China in the competition.

He then toured England and France. “I was wearing a white tie and tails,” he said. “I played at the Café de Paris, a real nightclub.”

During the tour, the promoter paid his mother $25 a month, while the boy received $1.25 a day in meal money. He had earlier won a bicycle, which to his boyhood eyes was the equal to having a Cadillac of his own. It was said his hands had been insured by Lloyd’s of London for £100,000, a fact dutifully repeated by newspapers. Left unreported was the duration of the policy, believed to have been a single day.

He returned home to Victoria for high school. Then, his mother wanted her son to go to China. “You’ve got a Chinese face,” she told him, “you’ve got to learn Chinese.” So he joined an older married sister in Shanghai, where he studied business at St. John’s University. Not long after his arrival, the Japanese seized the city, beginning a brutal seven-year occupation. He managed to skirt between two worlds as an ethnic Chinese whose nationality did not make him an enemy until December 1941.

Lowe was enlisted as a spy by Japanese intelligence, he once told Ricepaper, a Vancouver-based magazine, though he protected his friends and deliberately misled his handlers. He otherwise described a high-living wartime spent riding in Italian sports cars and going to jazz clubs. It was during the war that he became a broadcaster, reading English news reports on a station owned by his wealthy brother-in-law. He became a celebrity, his popularity peaking after the war. Lowe returned to British Columbia after the Communists took over the city.

By then fluently bilingual, Lowe was hired as a doorman by a club in Vancouver. Corrupt authorities turned a blind eye to gambling by Chinese Canadians, though not necessarily to lawbreaking by those of European ancestry. It was his job to ensure only bona fide club members entered the premises.

He sought work at local radio stations. Eventually, CJOR agreed to air The Call of China, a pioneering thirty-minute program that aired on Sunday afternoons.

“We tried to deal with everything authentically Chinese,” Lowe told a student publication in 1985. “I might be talking about pagodas, and I’d do research on that. Between each segment, I’d play a lot of Chinese music. There were more Canadian listeners than Chinese because the program was directed more toward them.” The show, believed to be the first in Canada with a Chinese-Canadian host, launched in 1951 and remained on the air for fourteen years.

Lowe became a prominent figure in Chinatown. In 1958, a Liberal senator contemptuously referred to Douglas Jung, a Member of Parliament from Vancouver, as “this Chinaman.” As president of the Chinatown chapter of the Lions Club, Lowe defended the MP, noting the senator’s words were “a great insult” and “objectionable because of its association with race prejudice.”

Lowe continued to perform with his yo-yos at such venues as the grand Orpheum Theatre and the bamboo-decorated Marco Polo nightclub, where he was stage manager. In 1971, the director Robert Altman asked Lowe to round up one hundred ethnic Chinese as extras for a movie he was shooting in West Vancouver with the working title, The Presbyterian Church Wager. Lowe enlisted friends, family and restaurant customers for a scene that, alas, wound up on the cutting-room floor when the film, retitled McCabe & Mrs. Miller, was released in 1971. He is credited in the movie in a role as a townsman.

It was during the filming that the actress Julie Christie, a noted perfectionist, asked Lowe to show her the proper technique for the ingestion of opium. Though he had never used the narcotic himself, he consulted old-timers in Chinatown and got the information.

May 12, 2009