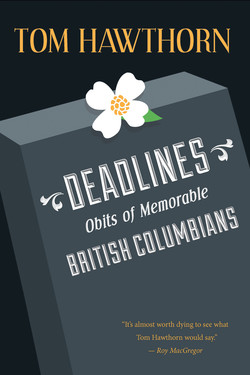

Читать книгу Deadlines - Tom Hawthorn - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAlberta Slim

Yodeling Cowboy Singer

(February 2, 1910—November 25, 2005)

Pearl Edwards

Pearl the Elephant Girl

(October 7, 1922—March 18, 2006)

Best known as the singer Alberta Slim, Eric Edwards was an English-born yodeling cowboy who rode the rails of Western Canada during the Depression, stopping along the way to coax coins for his supper from passersby by singing hobo songs on street corners.

After he built a career as a western singer on radio in Saskatchewan, he returned to touring the country, both as a singer and with his own travelling circus. On one such barnstorming journey through the Maritimes, he was inspired by a fragrant springtime phenomenon to write When It’s Apple Blossom Time in the Annapolis Valley.

That song would become his signature. Edwards’s verse was simple in construction and heartfelt in delivery. He performed until 2003 when, at ninety-three, a variety of infirmities at last made it impossible for him to follow the open road.

An irrepressible performer, Edwards had a predilection for cowboy shirts and white stetsons. He never willingly surrendered a microphone. He was, by his own admission, a yodeling fool, as likely to launch into an extended call in the middle of conversation as he was to do in song. “That yodeling don’t go with it,” he said with a whoop on one such occasion. “I just did it for the hell of it.”

Eric Charles Edwards was born at Wilsford, Wiltshire, a village near Salisbury Plain in England. His father, who drove a taxi and ran a pool hall, moved the family to nearby Upavon after returning from service in the Great War. While working as a publican at Larkhill, the descriptions of Canada by homesick Canadian soldiers billeted in the area persuaded him to immigrate to a land he had never seen.

The Edwards family purchased three quarter-sections of ranchland near the Saskatchewan side of Lloydminster in 1920. A move to St. Walburg came two years later. Music provided entertainment at home, as father fiddled and mother played an organ, while the four boys and three girls joined in on banjo and guitar.

The cowboy crooner left home as a young man with a guitar and $25 raised from selling his horse to a neighbouring rancher. He hopped a train to Edmonton, where he bought three guitar lessons before auditioning at a local radio station. While awaiting word on the job, he wandered the streets, stumbling across an old man playing a whistle pipe who invited him to join in. It was the first but not the last time he would eat thanks to busking.

The radio station did not hire him. Instead, a sympathetic staffer put him in touch with an English couple whose attempts at homesteading had failed and who were desperate enough to revive a career as entertainers. They bought a four-door touring car and hit the road with their twelve-year-old son and the yodeling cowboy. They earned blessed little, and the boy and the singer were often reduced to stealing vegetables from private gardens. The unlikely foursome called it quits when the couple could not afford the $30 monthly payments for the car.

Edwards spent the Depression years blowing across the country like a tumbleweed, courtesy of the freight trains on which he hitched an unpaid ride. He took to sidewalks to sing songs such as Waiting for a Train when he needed to fill an empty belly.

In 1937, he had a meeting with a store owner that would take him off the streets. Broke and hungry on arrival in Regina, he headed for the Salvation Army, as the Sally Ann “always had a meal for us and a flop in a dormitory.” He learned from the hobo grapevine that the Army and Navy Store sponsored a half-hour amateur show on radio station CKCK. The only payment was a free breakfast, reward enough for hungry men.

The singer went to the store, told the owner he intended to perform on the show, and asked for clothes to replace the rags he was wearing. Sam Cohen outfitted him with a pair of pants. The singer’s rendition of Wilf Carter’s There’s a Love Knot in My Lariat won him an offer to be a daily regular on the show.

He earned money for room and board at the Regina Café, where he was allowed to pass the hat after each performance. He also earned tips by reading tea leaves. One day, he gazed into the drained cup of a nineteen-year-old farm girl and predicted that Pearl Griffin would become his wife. In this one instance, at least, he was presceint.

Pearl Evelyn Griffin was born in Lestock, a small community in south-central Saskatchewan, about a hundred kilometres west of Yorktown. Her family traced its roots on the prairie to John Pritchard, an early Red River settler. Pearl was the sixth of seven children born to a midwife and a drayman. Her father supported the family during the Depression by holding five jobs.

She left the village for Star City, located nearer Saskatoon. There, she moved in with relatives to complete Grade 12, which was not offered in her hometown. The local telephone exchange was set up in the home, so she worked as an operator to pay for her room and board.

She soon found similar work in Regina. It was on her first day off that she joined a friend at a downtown café where a cowboy singer made his bold prediction of marriage. They married two years later in 1943 and for the duration of their union the bride addressed her husband as Slim.

Edwards had taken the name years earlier while on the road as a yodeling cowboy. He had a partner, a singer who called himself Alberta Slim, who enlisted in the armed forces when war broke out in 1939.

As Edwards recalled, “The guys on the freight all joined up. They wanted to eat. Me, I didn’t want to fight. He gave me all his clothes. I started wearing his silk shirts with Alberta Slim written across the back. They began calling me Alberta Slim and that’s the way I got it. Never saw him again. I heard through folks he was killed overseas.”

Edwards was hired by station CFQC in Saskatoon to perform a fifteen-minute show three mornings each week for a princely $4.50. After four months, his workweek and payment were doubled. He supplemented his income by offering listeners a chance to purchase a publicity photograph. He was not permitted to sell the pictures over the air; instead, he asked ten cents for shipping and handling. He got a bag of mail each day and soon had enough money to buy a trick horse with which he would perform at local rodeo shows, appearances that he would promote over the radio. After four years, he moved his act to CKRM in Regina.

Edwards performed on the radio in winter and followed the carnival circuit in summer. He had a 350-person tent, a backup band called the Bar X Boys, and a trick horse named Kitten. The horse had a repertoire of stunts, including knot untying and kneeling in prayer. For what was called the automobile act, she rested on her back while Edwards sat on her belly holding a front hoof in each hand, as though steering.

At each show, a young girl from the audience was brought before Kitten. Asked how many children she would bear, the horse would slowly paw at the dirt, until the crowd collapsed in laughter as the count reached thirteen, fourteen and sometimes fifteen.

The travelling menagerie eventually included Babe the singing dog, Blackie the high-diving dog, and Butch the walking Dalmatian, who could traverse 400 metres on his hind legs while carrying a 2.5-metre pole balanced on his front paws. Pearl Edwards performed in the circus as a featured attraction billed as “Pearl the Elephant Girl.” Dressed in frilly costumes of her own design and making, her act included standing on the shoulders of a rearing elephant named Susie. The talented pachyderm was also capable of playing the harmonica, a skill that eluded her biped partner.

Edwards moved his radio show to CKNW in New Westminster in 1947, when much of the listening audience on the outskirts of Vancouver was still living a rural life. He began recording in Toronto in 1949 for RCA Victor, releasing singles and albums on the Camden label. Many of his compositions were also recorded by other artists, including My Nova Scotia Home, My Fraser Valley Home and Beautiful British Columbia. He had a penchant for Wilf Carter tunes, several of which can be found on his recordings. A man whose livelihood had depended on keeping abreast of technological change—from radio to 78 rpm records to 33⅓ vinyl to cassettes to compact discs—was not cowed by the computer age. Alberta Slim sold music online from his personal website.

Edwards and his wife moved to New Westminster outside Vancouver in 1947, later settling on the south side of the Fraser River in Surrey. They wintered in British Columbia and spent their summers criss-crossing the nation.

The couple decided to abandon their itinerant life after the birth of their second child. The circus critters were sold, save for Kitten Jr., which was taught a repertoire of tricks in the family’s basement. The colt performed at charity functions.

Alberta Slim continued to record and perform, while Pearl Edwards operated the family’s Bar X Motel on the King George Highway. The couple also operated a mortgage brokerage business known as Bar X Enterprises, through which they purchased, improved and resold residential properties.

Every August, Pearl returned briefly to her former carnie life by working the midway at the Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver. Her game was Duck Pond, in which a small prize was guaranteed all players. It was her particular skill to encourage fathers and boyfriends to spend large sums—one quarter at a time—in an effort to win a large stuffed animal.

A year before his death, Alberta Slim released a cassette tape including a new composition, The Phantom of Whistler Mountain, to celebrate the awarding of the 2010 Winter Olympics.

While cowboy music fell out of style long ago, Edwards enjoyed a revival in recent years for his dedication to an almost-lost form. His ninety-second birthday was celebrated at the Railway Club, a hipster hangout in Vancouver. He also performed at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival and the Stan Rogers Folk Festival in Canso, Nova Scotia. A display honouring Edwards can be found at the Apple Capital Museum in Berwick, Nova Scotia, in the heart of the Annapolis Valley. In 2003, he received a lifetime achievement award from the BC Country Music Association.

That same year, he appeared on the main stage at Rootsfest in Sidney, north of Victoria. His appearance at a workshop with Amy Sky, Stephen Fearing and John Mann of Spirit of the West was notable for the enthusiasm of Edwards’s yodeling. His white hair cascading past his shoulders, a cowboy hat on his head, he yodeled until he was nearly hoarse, as though he knew time was limited and he had better yodel while he could.

December 6, 2005