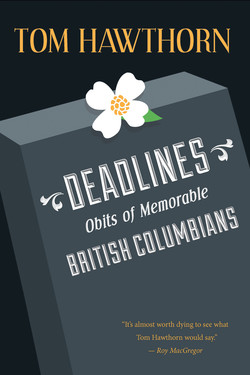

Читать книгу Deadlines - Tom Hawthorn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

In these pages you’ll meet some fascinating people. They have two things in common—they all have a connection to British Columbia and they’re all dead.

You’ll meet an aviatrix and a Communist; a boxer named Baby Face and a wrestler called Mean Gene; a yodeling cowboy singer named Alberta Slim and the real-life model for James Bond.

Spoony Singh won and lost fortunes in the sawmill business in British Columbia before opening the Hollywood Wax Museum. Bergie Solberg lived a hermit’s life in the bush on the Sechelt Peninsula, where she was known as the Cougar Lady. Doug Hepburn, born cross-eyed and with a club foot, became the world’s strongest man.

Donald Hings was an inveterate tinkerer credited with inventing the walkie-talkie. Cecil Green was a poor schoolboy who went into electronics, making a fortune at Texas Instruments that he then proceeded to give away.

An obituary is a profile in which the subject cannot grant an interview, so we obituarists behave as newsroom jackals, rending bits of reportage and quotation from reporters who have come before. Perhaps it is for this reason the obituary desk is considered the lowest spot in the newsroom hierarchy. It is a job most typically assigned to cub reporters and burned-out veterans, recovering alcoholics and those who still seek inspiration in the bottom of a bottle. In his novel The Imperfectionists, Tom Rachmann describes the end product of an obituarist’s workday: “decades of a person’s life condensed into a few paragraphs, with a final resting place at the bottom of page nine, between Puzzle-Wuzzle and World Weather.”

Luckily for me, most of these stories originally appeared in the Globe and Mail, for which I also write a human-interest column twice a week. The Globe dedicates a full page of every edition each publication day to obits, following a path blazed by the late Hugh Massingberd, the obituaries editor at The Telegraph in London. As his obit in that paper noted, he “had to reinvent the whole concept of the form, substituting for the grave and ceremonious tribute the sparkling celebration of life.”

Writing an obituary is the most intimate thing you can do with someone you will never meet. I have leafed through diaries, comforted bereaved spouses and uncovered details that even the family doesn’t know.

The resulting stories are neither tribute nor eulogy, nor are they written for the benefit of surviving family members. They are intended to enlighten the reader with anecdotes from a life of interest, giving voice to those who no longer have one. Treat these entries as you might those found in the daily newspaper. Dip into two or three each day, catching up on the passing parade of characters.

Have Christmas dinner in the ruins of an Italian church as enemy shells land nearby; listen to the voice of Casper the Friendly Ghost from Saturday morning cartoons; track the Mad Trapper of Rat River across a frozen mountain pass with a police posse; wince from the blows of police truncheons on the head of labour leader Steve Brodie on Bloody Sunday; laugh at the televised misfortune of a snooker player who split the seat of his pants on national television.

In these pages, death is mere detail. These are tales about how lives were lived.

—Tom Hawthorn