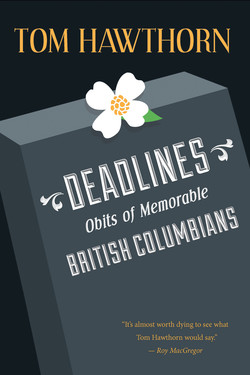

Читать книгу Deadlines - Tom Hawthorn - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSpoony Singh

Proprietor, Hollywood Wax Museum

(October 20, 1922—October 18, 2006)

Spoony Singh drove a gold Cadillac and preferred a Nehru jacket to a business suit. Though he was not particularly religious, he wore the turban and full beard of an observant Sikh. Patrons of his Hollywood Wax Museum sometimes mistook the proprietor for an exhibit.

The museum, which opened its doors to a half-mile lineup in January 1965, featured lifelike wax statues of presidents and movie stars, as well as religious figures and famous characters from history. A favourite among the faithful was a tableau depicting Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. When a patron complained the museum lacked Jewish heroes, Singh promptly ordered a model of Moses—or, rather, of Charlton Heston as he appeared in The Ten Commandments.

Over time, the flamboyant businessman became nearly as famous as some of the stars to be found inside his attraction. He rode an elephant in parades and appeared regularly in gossip columns. “My family left India because we couldn’t get enough to eat,” he told Hedda Hopper. “Now, I’m paying a doctor to lose weight.” Singh let it be known a rising star had not truly achieved a place in the Hollywood firmament until honoured by placement in his museum.

On November 7, 1965, Singh joined a woman who sold dynamite and another who wrote a syndicated sports column as guests on the network television program What’s My Line? His profession stumped the panel.

He was a showman whose ballyhoo made his museum a great success. The money generated from the tourist attraction built a business empire featuring farming, gold mining and warehousing interests. He also developed property in Mexico and Malibu, the California seaside paradise where he made his home. “I’m making money,” he said in a 1970 interview, “and I’m having a ball.”

Success was all the more remarkable for his having been born into poverty in India. He grew up on Vancouver Island, where his ambitious plans and prodigious energy built a small fortune, which was soon lost. He recovered, only to suffer as many failures as triumphs before striking it rich in wax. His was a life story worthy of Hollywood.

Sampuran Singh Sundher was born at Kotli, a farming village in the hilly Punjab country of British India. Three years later, the village raised funds to send the family to Canada, a generosity whose motive is today unknown, although the Punjab then, as now, was a place of political and religious turmoil.

The family landed in Vancouver just eleven years after the notorious Komagata Maru incident in which a boatload of Sikh immigrants was forced to spend two months at anchor in the harbour before being turned away. The Sundhers settled in Victoria, where his father worked in a sawmill and young “Spoony,” as he was nicknamed by classmates, attended Quadra Elementary and Victoria High School.

A quiet segregation in public spaces was reinforced by federal and provincial laws denying Indo-Canadians the franchise, as well as jobs in the civil service, including teaching. Spoony watched movies in Victoria theatres, where he had to sit in the balcony with aboriginal and ethnic-Chinese patrons. Seats on the ground floor were reserved for whites.

His father suffered a business failure and became incapacitated by asthma the summer Spoony graduated from high school. At seventeen, Spoony became the primary breadwinner of a family of six. He found work in a shingle mill, saving money to buy a truck to deliver firewood to homes. He was hired as a foreman at a piecework lumber mill, only to have the day shift walk out to protest having to work for “a Hindu,” said his son, Meva Sundher. When Singh was instead assigned to the night shift, his reforms so improved production that day-shift workers asked to work split shifts to reap the benefits.

A shrewd entrepreneur, Singh parlayed this modest beginning into a thriving enterprise. He built Ace Sawmill at Plumper Bay in Esquimalt and operated a logging camp near Port Alberni. He was also responsible for the logging on the north slope of Mount Newton on the Saanich Peninsula north of Victoria. While his son said he had to declare bankruptcy more than once, Singh had enough success by 1954 to build a gracious, four-bedroom private home in the Art Moderne style on Peacock Hill in suburban Saanich. By then, he had married Chanchil Kour Hoti in a union arranged by their families. The pair only agreed to marriage after insisting on going out on chaperoned dates. The residence at 3210 Bellevue Road, no longer in family hands, has been designated a heritage house.

The forestry industry has always been a boom-and-bust business. Singh diversified his interests and satisfied his own fun-loving spirit by opening a roadside amusement park called Spoony’s. He offered trampolines for acrobatic guests and built his own go-karts powered by motors scavenged from chainsaws.

While enjoying drinks with his cronies at a Victoria bar, Singh learned of a business opportunity. A former luggage shop and brassiere factory was vacant at 6767 Hollywood Boulevard, just a block east of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and its famous sidewalk with the handprints and footprints of the stars. With the theatre already famous as a draw, the wax museum became a second landmark destination for tourists. Suspecting a better cover story might generate interest, Singh told reporters he opened the museum because he had been shocked on a visit not to have seen any stars on the streets of Hollywood.

The owner was a natural at generating publicity. A 1965 preview offered writers “Bloody Marys and horror d’oeuvres.” Another time, he got Louis Armstrong to pose beside a paraffin doppelgänger while blowing a trumpet. The photograph ran in several newspapers. The Chicago Daily Defender, with an African-American readership, noted the problem of identification in the caption. “He’s on the left . . . no, he’s on the right . . . wait a minute, let me think . . . that’s the real ‘Satchmo’ on the left.”

Populated mostly by movie stars (Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Errol Flynn, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields, Tallulah Bankhead, Rudolph Valentino), the museum later added more figures from television and pop culture, including Glen Campbell and Sonny and Cher. A figure of Martin Luther King was installed within weeks of his assassination in 1968.

A typical shopping expedition for Singh included purchasing unwanted movie props—an Iron Maiden, a bed of nails and a rubber shark from which protruded a man’s leg. He also came to own a pair of pajamas that had belonged to Playboy founder Hugh Hefner.

Petty thievery cost the museum about $200 every month, as customers made off with Gandhi’s spectacles, Winston Churchill’s cigars and Raquel Welch’s brassieres. The owner suspected teenagers were responsible. “At that age,” he chuckled, “I probably would have done the same thing myself.” The four Beatles were displayed behind glass, from which lipstick imprints had to be cleaned before the start of business every day. Despite the security precautions, someone once stole the right hand of drummer Ringo Starr. A wire-service story on the thefts earned Singh far more in publicity than it cost to replace props.

More serious vandalism occurred in 1973, when twenty-nine figures were mutilated overnight. Among the victims were Elton John and six presidents (Grant, Hoover, Truman, Coolidge, McKinley and Eisenhower). The religious statues were left untouched, as were presidents Nixon and Kennedy. A fire six years later damaged about seventy figures at a cost of more than $250,000 US. The casualties included Stalin and Churchill, as well as Raquel Welch.

With the museum as the anchor of a growing empire, Singh indulged such other interests as gold mining in Mexico and farming in Yuba City, California. He operated warehouses in Thousand Oaks, California; bought the movie theatre across the street from the wax museum, which now operates as the Hollywood Guinness World of Records Museum; and opened a second branch of the Hollywood Wax Museum at Branson, Missouri. The latter includes a faux Mount Rushmore with America’s greatest presidents replaced by busts of John Wayne, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe and Charlie Chaplin. This exquisite bit of kitsch was Singh’s idea.

Singh befriended many of the stars he immortalized in wax. One he did not get to meet was Marilyn Monroe, who appeared in the museum trying to hold down her white skirt in the famous scene from The Seven Year Itch. Singh, a fan of her obvious appeals, particularly enjoyed the whimsical nature of her display. He felt too many patrons left his museum in a sombre state after viewing The Last Supper. It was his long-unfulfilled dream to install a sidewalk air jet at the museum’s exit. That, he felt, would have left them laughing.

He died of congestive heart failure at his Malibu home two days before what would have been his eighty-fourth birthday.

October 31, 2006