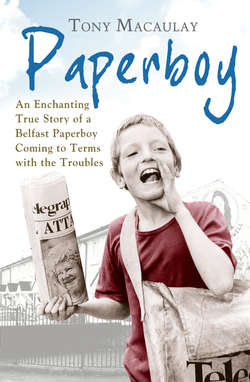

Читать книгу Paperboy: An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles - Tony Macaulay - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Hoods and Robbers

I knew there were risks to being a paperboy, especially on shadowy Friday nights when you had to collect the paper money for Oul’ Mac. The introduction of hard cash into the equation caused Fridays to be darker and more threatening than any other night of the week. Robbers were an occupational hazard, the main health-and-safety risk for a Shankill paperboy.

Other week nights, I was carefree. I would run down the street, slapping a folded newspaper all along Mrs Henderson’s steel railings to make a melody. It was like playing a big rusty xylophone. The faster I ran, the higher the notes sounded out. But there was no such joy on Friday nights. As darkness fell on the last day of the week, my mood would grow grave. For Friday night was when robbers came up from down the Shankill for easy pickings.

The papers themselves were heavier too on a Friday, because of the job advertisement section – but not much heavier, because there weren’t that many jobs. I sometimes looked through the employment pages to see what I might do when I graduated from newspaper delivery, but there was never anything. Then I noticed that there were always more death notices than job advertisements in the Belfast Telegraph, so I came to the comforting conclusion that by the time I was eighteen years old, enough people would have died for me to get one of their jobs.

There were undoubtedly pros and cons to collecting the paper money. At the caravan site in Millisle we went to every summer, I met paperboys who delivered in East Belfast, where they built the Titanic that sank. They didn’t collect the money because their Oul’ Mac didn’t trust them. At least our Oul’ Mac gave us the chance not to thieve! As a Shankill paperboy, I didn’t often get the chance to feel morally superior, but it felt good to be able to claim the moral high ground over East Belfast boys, because they seemed to think they were so much more Protestant than us. Apparently, East Belfast customers had to go to the shop to pay their paper money on the way home from the shipyard. The result of this was that the paperboys there only got one tip a year, at Christmas. This was the downside of having no financial responsibilities. No money, no robbers – but then again no money, no tips. Collecting the paper money every Friday night opened up the possibility of year-round tipping, so I soon decided that the benefits of regular tips outweighed the risks of being robbed.

Everyone loved Friday nights, as a rule. There was a lightness in the air, like on Christmas Eve and the Eleventh Night. Friday was the night you had no hateful homework. It was the night when Dad came home from the foundry, paid and happy, and he gave us boys 50p and Mum a Walnut Whip. (When he got overtime, we got a pound note each and she got a box of Milk Tray.) Friday was the night of Crackerjack at five minutes to five on BBC 1. Everyone in my street loved it, but I had to miss it. While all the other kids of my age were glued to the screen, trying to win a Crackerjack pencil – which was nearly as good as winning a Blue Peter badge – I was out in the dark, running the gauntlet of doing papers and collecting money. I was learning to make sacrifices for my career.

Growing up in the Upper Shankill, you soon learned that you were better than the people in the Lower Shankill. It was good to be better than someone somewhere. Any trouble or crime was usually blamed on ‘that dirt down the Road’. The houses were older and smaller down the Shankill – two up and two down, if you were lucky. Everyone down there was on the dole and smoked and nobody did the Eleven Plus.

We, on the other hand, lived in the Shankill’s only privately owned housing estate. So we were special. One lady on my paper round, who got a People’s Friend, always corrected you if you called it an ‘estate’. She preferred you to say a ‘private development’. We had front and back gardens in our estate, and not everyone put a flag out for the Twelfth. Our house had a phone, some of the neighbours owned shops on the Road, two of my customers had new Ford Cortinas, and a man in the next street was even a teacher.

Mrs Grant from No. 2 actually had a son at university. He had passed his Eleven Plus and gone to ‘Methody’ on the Malone Road. Mrs Grant said it was better than Belfast Royal Academy because there were no Catholics living anywhere nearby. Her son was a genius, and so he had gone to university in England. It was very important to her that everyone should know about Samuel’s academic achievements. If you ever found yourself in the queue behind Mrs Grant in the Post Office when your mother was collecting the family allowance or sending a postal order to the Great Universal Club Book, you would hear Mrs Grant ending every conversation with a noticeable increase in volume, and always with the same words: ‘Our Samuel’s still at university in England, you know.’ The whole queue would roll its eyes.

I never, ever saw Samuel. He was always at university in England, it seemed. Maybe he is still there. He was like Charlie in Charlie’s Angels. You heard a lot about him and all of his heroic achievements, but you never actually saw his face. Samuel didn’t seem to come home much, even though Mrs Grant talked such a lot about him, and her husband, Richard, was awful bad with his chest and throat and everything.

The kids in the council estate on the other side of the road called our warren of red-brick semis ‘Snob Hill’. They were jealous because we were so rich. Some of their rows of red-brick terrace houses were boarded up and we called them ‘smelly’. Of course, we were jealous of them too. They had shops and a green for their bonfire, a flute band and a community centre for paramilitaries, and the black taxis stopped right at the entrance to their estate. All we had was a telephone box, a post box and neat gardens.

Every year, one or two children from our estate, like me, passed the Eleven Plus and went to grammar school. We weren’t really supposed to. But regardless of this fact, my parents made education a priority, to the astonishing extent that passing the Eleven Plus was more important than not having a United Ireland. ‘No son of mine is going to end up in a filthy foundry like me,’ was my father’s refrain.

If doing the Eleven Plus meant that I was a snob, passing the Eleven Plus meant that I was a super snob. And going to a grammar school meant that I was Prince Charles. Yet, on my first day at Belfast Royal Academy, I would learn that I was much less of a snob than I could ever have imagined. There were not too many paperboys from the Shankill around. Not too many Shankill boys around at all, in fact. I had been an impressive angelfish in a small goldfish bowl at Springhill Primary School, but at Belfast Royal Academy I was a guppy with raggedy fins in the huge expanse of Lough Neagh. Wee hard men from the Lower Shankill delighted in reducing the Belfast Royal Academy to a breast-related acronym: ‘Have you been inside a BRA all day, ya big fruit?!’ they would shout.

It was at grammar school that I first discovered that most people made no distinction between Lower Shankill and Upper Shankill. We were all dirt.

The robbers from the Lower Shankill weren’t big-time hoods or paramilitaries. They weren’t like those Great Train Robbers or Jesse James on TV. Neither were they wee fat men in masks with black-and-white striped shirts and swag bags, like in The Beano. They were just wee hard men a few years older than me. I got stopped by them all the time. I guess I must have looked soft in my blue duffle coat and grammar-school scarf.

But, in spite of appearances, I was hard to rob. I didn’t fight. I couldn’t fight. Sure there were enough people in Belfast fighting anyway. So I just used my head instead. I kept an eye out for suspicious-looking teenage males in my streets on my patch on Friday nights. They were easy to identify. They walked like wee hard men, half march and half swagger. They wore tartan scarves and white parallel trousers and smoked.

Once I spied a suspected hood, I could disappear into the darkness through holes in familiar fences, under camouflage of garden hedges. Then, just in case my attempts at invisibility should fail, I hid the paper notes down my socks and dropped the coins down my boots. Robbers hadn’t the brains to suspect that my Doc Martens held a cash stash. They thought boots were just for kicking your head in. So, when they ordered me to empty my pockets, or else they would ‘smash my f**kin’ face in’, and when they searched my pockets for cash, they got nothing. You should have heard the victory jangle of coins in my boots as I leapt over prim Protestant hedges between semis after an attempted robbery. There was, however, a cost to my zealous protection of Oul’ Mac’s profits – painful blisters on my feet, from running on grinding ten- and fifty-pence pieces.

The worst part of being a Shankill paperboy was the constant fear that the robbers out there in the darkness would employ more violent techniques. It worried my parents too. I was under strict instructions from my father that I should inform him of any encounters with suspected robbers. I rarely did. I had worked out how to handle them myself. I used my head, like the Doctor preventing an invasion of Daleks. Instead of hand-to-hand combat, I too attempted to come up with a clever and cunning plan.

But one Friday night, it was different. The wee hood was only about sixteen, but he scared me. He wouldn’t give up. I had already done my disappearing act a couple of times. He had already stopped me once, used the obligatory ‘kick your f**kin’ head in’ threat, and made me empty my pockets. Of course the money was safely snuggled between my toes, but he took my chewing gum and my Thunderbird 2 badge. Even that didn’t seem to satisfy him, however. He kept hanging around and following me and I had to stop collecting money altogether.

The wee hood in question wasn’t much taller than me, but he was plumper, and his parallels and Doc Martens were worn. He wore his trouser legs higher up the shin than me. This was an important indicator of the level of potential threat. For girls, the higher the parallels, the bigger the millie. A ‘millie’ was a girl that smoked, said ‘f**k’ a lot and wound her chewing gum around her fingers between chews. A millie was the opposite of Sharon Burgess. They could be good craic, but you wouldn’t want to kiss one. With boys, the higher your parallels, the harder you were. My big brother’s parallels were always higher than mine. Of course, you had to be very careful. If your trouser legs went above your knees, then they just became shorts and that meant you were a fruit.

The wee hood’s hair looked like his ma had cut it. He looked like he couldn’t afford to get it feathered in His n’ Hers beside the graveyard. He was spottier than anyone in my class in school. He had even more spots than Frankie Jones in French who played the drums, liked heavy-metal music and hid dirty magazines in his schoolbag.

My assailant had a bizarre speech impediment. In all of his brief communications with me, he started every sentence with the word ‘f**kin’ ’. It was supposed to sound hard, but it just sounded peculiar:

‘F**kin’ wee lad, have you any money on ye?’

‘F**kin’ you there, who do you think yer looking at?’

‘F**kin’ when do you collect the f**kin’ money here?’

He was seriously interfering with the execution of my professional duties. So I slipped through a hole in the Coopers’ fence. All the Coopers had blonde hair and a turn in their eye, but their granda was brilliant at bowls and they got the Weekly News and a TV Times. I jumped over a few red-brick walls, landing uncomfortably on a bootful of loose change, and eventually arrived at my own back door.

‘Dad, there’s a robber!’ I said breathlessly as I burst into the house, kicking off my boots and launching a fleet of coins across the sitting-room shag pile. My father had just changed out of his dirty blue foundry overalls into his new beige trousers from the Club Book.

‘Right!’ he barked angrily. ‘Where is the wee bastard? Show me!’

I knew he meant business when he stubbed out his cigar in the seashell ashtray from Millisle. He had given up chain-smoking cigarettes because they gave you cancer. Now he chain-smoked Hamlet cigars instead. The living room was just as smoky, but I preferred the smell. Daddy particularly enjoyed smoking a Hamlet cigar, while sipping a black coffee and sucking cherry menthol Tunes as he watched a documentary on BBC 2. ‘Your father’s a very clever man,’ my mother would say. I think she was referring to the documentaries.

Dad went upstairs straight away and took out the large wooden pickaxe handle from under his bed. This had appeared under my parents’ bed when the Troubles started. I think it was meant to be our family’s protection against a rumoured IRA invasion of our estate. The Provos seemed somewhat better equipped, so I had worked out an escape plan to hide in the roof space when they attacked. I had devised the exact same plan should there ever be a Dalek invasion, because I knew they wouldn’t be able to use the stepladders.

Within seconds, we were in our red Ford Escort respray on the trail of the wee hood. I was now more shaken by the commissioning of the pickaxe handle than by the robber. I didn’t regard my father as a violent man. Yes, he gave me a few hidings with the strap for my cheek, but he wasn’t a fighter and he scorned the paramilitaries. ‘No son of mine will be getting involved with any of those paramilitary gabshites!’ he would pronounce regularly.

We drove around the estate a few times, searching for the robber. I got a surge of excitement with the realisation that the predator in parallels had now become the prey. My father would grab the wee hood, bring him back to our house and phone the police. The police would bring him home to his wee two-up, two-down. His Da would give him a good hiding and he would never attempt to rob a paperboy again.

But what happened next shocked me. I spotted the robber at the top of another paperboy’s street. I pointed him out. My father abruptly stopped the car, pulling up the handbrake with a screech.

‘You stay here!’ he commanded, as he grabbed the pickaxe handle from the back seat and sprang out of the car. He ran up behind the wee hood in the dark. It was raining now, and everything looked blurred through the windscreen. I watched my father unleash the weapon with force across the wee lad’s back. I feared he was going to kill him.

The hood stumbled on the impact, yelped like a beaten dog and ran for his life. Now I felt sorry for him. All this for a packet of Wrigley’s and a Thunderbird 2 badge. Dad had hit him so hard that he had lost his own balance and landed in a puddle on the pavement in his good trousers and cut his hand on the kerb. He looked like Captain James T. Kirk, after fighting a monster alone on a dangerous alien planet, all sweaty and bloody, determined to save the crew of the USS Enterprise. By this stage, however, I just wanted him beamed up as quickly as possible.

‘That’s the end of him!’ my father announced when he returned to the car, soaked, breathless, bleeding and sweating.

‘It nearly was!’ I thought. ‘No son of mine is gettin’ robbed by no wee hood!’ Dad proclaimed.

I had expected the robber to be brought to the police: now I was afraid the police would arrest my father. Fortunately, the RUC had other priorities at the time.

My father drove us home very quickly, and his heavy breath steamed up the inside of the windscreen. This was the same car we went on picnics in. Within a few minutes we were back home and he was just Dad again, falling off the sofa, laughing at posh Englishmen talking to a dead parrot on Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

My mother was appalled by the state of his soaked and shredded slacks. She had fifteen more weeks at 99p to pay for them, and now they were ruined. She ended up using them to clean the windows. But I knew she was secretly pleased by the protective pickaxe blows for her son. She tended to Dad’s injured hand like Florence Nightingale nursing the soldiers in my school history book. She called him ‘Eric, love’ and he called her ‘Betty, love.’

Everything was all right again. I felt safe and protected by the strength and toughness of this new action-hero dad. He was like Clint Eastwood, only bald with glasses, and this Wild West was in Belfast.

I understood that this was the Northern Ireland way. If someone hits you, you hit him back harder. It felt satisfying and powerful, but I knew this way solved absolutely nothing. I saw it every day in Belfast. Tit-for-tat for tit-for-tat. An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a Catholic for a Protestant. Men excusing heinous acts of inhumanity to protect or liberate ‘their’ people, belligerently sowing pain and bitterness for generations to come. I suppose it made them feel potent and powerful too. I got a little taste of it that night with my father and the wee hood, but I spat it out. It sickened me. There had to be another way. I resolved that I would be Belfast’s first pacifist paperboy.