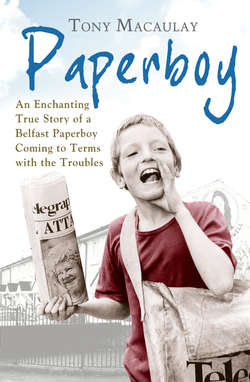

Читать книгу Paperboy: An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles - Tony Macaulay - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Secrets in School

Being a paperboy had to be a secret once I started Belfast Royal Academy, as I soon learned. Living up the Shankill, having a Ford Escort respray and a father who worked in a foundry near the Falls Road were just a few of the other facts best kept hidden. No one ever said it out loud, but I picked up the cues from the dominant rugger boys that this information was best kept discreetly folded away – like the Woman’s Own you kept at the bottom of your paperbag for the middle-aged man with dyed hair who still lived with his mammy in No. 91.

I thought I had more secrets to keep than James Bond, until I got to know Thomas O’Hara, another wee boy in my class with something to hide. I had never met any ‘O’’ anythings before. It was whispered in the playground that wee Thomas with the curly hair and freckles was, in fact, a real Catholic. This was confirmed when someone overheard him saying ‘Haitch Blocks’ instead of ‘H Blocks’. And David Pritchard, who didn’t believe in God and rebelliously refused to close his eyes during prayers in Assembly, had spotted Thomas crossing himself at the ‘Amens’. David, evidently a Protestant atheist, was appalled and told everybody.

Wee Thomas was the first Catholic I had ever spoken to, although I had once sung along with Val Doonican’s rendition of ‘Paddy McGinty’s Goat’ from his rocking chair on BBC 1 on a Saturday night after Doctor Who. At eleven years old, I was very young to be meeting one of ‘the other sort’ for the first time. Most people in Belfast left it until they were at least eighteen, or preferably never did it at all. Titch McCracken said you could tell someone was a Catholic if their eyes were too close together, but I wasn’t convinced, because one of the other paperboys, Billy Cooper, was practically cross-eyed, but he played a flute in The Loyal Sons of Ulster Band. And you couldn’t get more Protestant than that.

I would get the biggest shock I had had since John Noakes announced he was leaving Blue Peter when remarkably – against all the odds and contrary to all that I had heard from both heaven and earth – I realised that wee Thomas O’Hara was in fact dead-on. Before this, my primary experience of Catholics had been limited to cross men on Scene Around Six who made my father shout. Of course, Dad also yelled when the Reverend Ian Paisley came on the news, which was baffling because Big Ian was the opposite of a Catholic. And while my granny said Paisley was ‘our saviour’, my father called him ‘Bucket Mouth’. All the other paperboys said, like Granny, that without Big Ian we would be ‘sold down the river’, but I could never work out where the river was. Maybe it was in Ballymena.

I made friends with wee Thomas on my first day at grammar school. Out of all the boys and girls in my class, he was the only one who wasn’t wearing a brand-new school uniform in the first week. He told me he was getting his blazer at the weekend, but when I told my mother, she said,‘God love that poor wee Catholic boy; they can’t even afford to buy the crater a uniform!’ This seemed to clash with the proud assertion I had often heard, that ‘we’re just as poor as them, you know.’

In fact, Thomas proved what I had always suspected, but would never have dared to articulate to either my paperboy peers or my Sunday school teacher: that Catholics were just the same as us! I couldn’t understand why such an astounding discovery had never made the front page of any of the Belfast Telegraphs I delivered.

Wee Thomas was one of the few people in my class who would have made a good paperboy, and he was certainly much more like me than any of the rugger boys. They made clever jokes in the rugby changing rooms about sheep and masturbation, but they never dropped a single ‘ing’. The rugger boys at school were the first people I ever heard putting a complete ‘ing’ onto the end of ‘f**k’, and it just didn’t work. They thought they were dead hard, eff-ing and blind-ing, but I thought they sounded ridiculous because I knew what real effin’ and blindin’ was. They were in their element kicking each other in a scrum, but I wondered how they would deal with hoods and robbers on a Friday night up the Shankill.

The only difference between Thomas and me was that he didn’t make a secret of who he was or where he lived. Unlike me, he didn’t seem to feel the need to keep secrets at school. Maybe my shame at not being prosperous was pure Presbyterian. Once wee Thomas and I became friends, I even learned that he was from Ardoyne, where the IRA lived. Of course, I never asked him if he wanted a United Ireland, worshipped Mary and supported the IRA. I just assumed he must be one of the ‘good ones’ who didn’t do all that.

However, one thing that I knew for sure was that wee Thomas and I shared an aspiration for something far more important than fighting between Catholics and Protestants. We were both willing to set aside all ancient rivalries for the sake of a common purpose – to dominate the pop-music charts. Along with two other school friends, me and wee Thomas decided to start a rock band. The other members of the band were Ian, who got the New Musical Express and sang in an English accent, and Stephen, who played a tambourine like David Cassidy. We wanted to be Status Quo, but we had limited talent and resources. All we had was my split Spanish guitar and an old bodhrán from Thomas’s granda’s shed. I never told my granny that I was in a band with an Irish drum, as I assumed this might be dangerous territory.

Although we tried very hard, we could never make ‘Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley’ sound like Status Quo. We decided to copy ABBA by using the first letter of each of our names to spell out the name of the band. We would be just like Agnetha, Björn, Benny and Anni-Frid. However, this idea proved problematic when we realised we had Thomas on drums, a lead vocalist called Ian, Tony on lead guitar and a tambourine player called Stephen . . .

The TITS were doomed. We split up during rehearsal one day, before playing even one gig at the scout hut, when I mistakenly expressed an interest in the forthcoming Bay City Rollers concert in the Ulster Hall. Ever since Pammy Wynette had told me the Rollers were coming to Belfast, I had been scouring the Belfast Telegraph announcements pages every night for news of dates and prices. My customers were even beginning to notice that I was ten minutes late every night. When, at band practice at Ian’s house one day, I casually mentioned that I was engaging in this research, the revelation exposed deep and unexpected artistic differences within the TITS. Ian was very angry. He said he was too serious about rock and roll to be in a band with a guitarist who wanted to see ‘them bloody teenybopper sell-outs’ in concert.

I didn’t know what a ‘teenybopper sell-out’ was, because I didn’t read the New Musical Express, but Ian seemed to take it to heart. I was just innocently hoping that the Rollers concert wouldn’t be sold out before I could get a ticket, but Ian said members of the TITS should only go to see serious rock bands, like Status Quo. He accused the Bay City Rollers of not being able to play their own instruments. I thought this was ironic, because we had been experiencing exactly the same difficulties ourselves. Ian sneered that the Scottish superstars should be called the ‘Gay Shitty Fakers’, and finally announced with an arrogant flourish that he no longer wanted to be one of the TITS. He threw down the handle of his little sister’s skipping rope, which he had been using as an improvised microphone, and walked out of the band practice, slamming the door behind him. (The dramatic effect was spoiled slightly when he had to come back in again because we were in his sitting room and his mammy had wheeled in a hostess trolley with cups of tea she had made for us and an apple tart.)

Ian’s walkout left the band without a lead vocalist, and without a vowel. Stephen would soon follow. He said he wanted to concentrate on disco dancing and that he had never been that interested in the TITS anyway. Thomas and I realised that we couldn’t go on as a duo, even though we knew it was working well for Donny and Marie Osmond, and so we decided to concentrate on solo projects.

The teachers at BRA occasionally provided us with a clear insight into our place in the world. In my first week at school, we were informed that we were in ‘the top one per cent’ in Northern Ireland. This felt good. A few weeks later, the same teacher said,‘God help us, if this is the top one per cent.’ This did not feel so good.

The school buildings were an interesting architectural reflection of the history of Belfast. They ranged from eighteenth-century Gothic granite to the 1970s red-brick style peculiar to Belfast, which featured as few breakable windows as possible. There was a swimming pool with no windows that smelt of Domestos and was always too warm. This was where I got my 100-metres front crawl badge and two verrucas, and where I laughed cruelly at Martin Simpson when he still needed armbands in Third Form, which made him cry.

In the most historic part of the school building was the Holy Grail of BRA: the framed charter conveying royal status on the school. The headmaster introduced us to it in our first year, with hushed and reverent tones. I had never seen a royal signature before, although my granny had a mug of Princess Anne’s wedding to Captain Mark Phillips. There was nothing in the world more important than being British. It was the opposite of being Irish. It was what you were supposed to kill and die for, although no one ever told me why. And you could hardly get more British than being royal. The Queen and King Billy were both royals, and they were nearly as British as Ian Paisley.

BRA was full of long corridors, which was good when you wanted somewhere quiet to snog a wee girl during lunch break, but bad when you were hurrying to Mr Jackson’s maths class, because if you were late, he would rap his knuckles on your head so violently that you would have to try hard not to cry in front of your classmates. Outside the school dining hall, the walls in the corridor were covered with pictures of the glorious First XV rugby team, going back a thousand years. As we queued up for vegetable roll and mash and pink custard, we would examine the pictures from the 1940s, recognising some of our ageing teachers as spotty scrum halves. We debated as to what could possibly have possessed them to come back to teach here.

When it became clear that I would not be following in the studded boot steps of my rugby-playing brother, my form teacher cheerfully informed me that I would therefore be spending the rest of my school years ‘in oblivion’. From that day forward, I found it almost impossible to develop an adequate appetite while queuing up for school dinners due to being surrounded by generations of rugger boys smiling smugly down at me. Of course, it could have been much worse, I reasoned. Apparently, there was a wee lad in Second Form who got free school dinners!

I would go on to make friends with kids from up the Antrim Road who lived in detached houses with flowering pink cherry trees, and whose fathers drove Rovers and read clever newspapers like the Daily Mail. No one ever ordered the Daily Mail up our way. Not one edition of it had ever graced my paperbag. My new-found friends talked about another world – of discos in the Rugby Club, fondue dinner parties and a glass of wine with Sunday lunch. Most of the other kids’ dads came to the school concerts, and I noticed when they clapped that they all had very clean hands. A lot of them had good jobs in the bank. Working as a banker was the ultimate job if you weren’t smart enough to be a doctor.

Some of my friends’ dads even played golf with the teachers. When I enquired of my father why he did not participate in this particular pastime, he replied with some disdain that it was a ‘middle-class sport’, and that ‘no son of his would ever be playing golf’. I added this command to the ever-lengthening list of things that no son of his would ever do, and, interestingly for me this particular forecast turned out to be accurate. ‘You’re working class and don’t you ever forget it, son,’ he would often say.

Much as I resented this edict of my father’s, at Belfast Royal Academy it was absolutely impossible to forget it. I soon learned the rules. When friends asked me where I lived, I said something vague like, ‘On the edge of North Belfast.’ This sounded more posh and less Catholic than West Belfast. Sometimes I would say ‘Beside the Black Mountain,’ as opposed to Divis Mountain, which sounded too much like the notorious Divis Flats. Now and again I would say ‘A couple of miles from school,’ which was technically true but sufficiently vague to mask my Shankill shame. On the few occasions that I would get a lift to school in our old Ford Escort, and even after the respray, I made sure I got left off around the corner, where no middle-class mate’s eyes would spot my modest mode of transport. I once got a lift with a friend from the Antrim Road whose father was a jeweller who drove a BMW. He left us off at the front gates of the school, and I waved goodbye to him as he drove away, with a certain ‘he’s my father, you know’ look on my face. Wee Thomas O’Hara had just got off the bus across the road and observed this pretentious behaviour. He said nothing, just looked straight at me and rolled his eyes.

But bigger circumstances conspired against me, again and again. Street unrest, Ulster Workers’ strikes and hunger strikes exposed my secrets at school, as well as disrupting my newspaper deliveries. Being late, or not being able to get to and from school at all because of burning barricades was a bit of a giveaway. Worse still, having to walk to school wearing no school uniform – so as to avoid the danger of having your religion written all over you – tended to expose the secret of the area you lived in. The days that half a dozen kids, usually including Thomas and me, were the only ones in class not in uniform were like those bad dreams where you go to school in your pyjamas.

On one such day, I overheard a cocky classmate, Timothy Longsley, whose brother played in the glorious First XV rugby team, whispering conspiratorially in Chemistry to Judy Carlton (who I fancied): ‘He lives in one of those rough areas where the bigots burn the buses, you know.’

‘Who do you think you’re lookin’ at?’ I shouted aggress-ively across the test tubes. I felt like a piece of phosphorous that was just about to ignite in oxygen.

‘None of your f**k-ing business!’ Timothy snorted back. He had stabbed me with an obscene ‘ing’. His daddy was a lawyer and his mother wore a fur coat and too much make-up at the School Prize Giving, where his brother always got a prize for Latin.

Judy Carlton looked at me sympathetically, but not without a certain sparkle in her lovely blue eyes. I noted this, admired her lips and filed this reaction away for future analysis. I resisted my urge to assault Timothy with a conveniently lit Bunsen burner, as I thought it would just prove his hypothesis. Anyway, I knew this would not be an appropriate course of action for the only pacifist paperboy in West Belfast.

Sometimes it seemed that there were always secrets to be kept, no matter where you went. At orchestra practice at the School of Music on Saturday mornings, I met lots of other Catholic kids who went to grammar schools on the Falls Road. That really threw me. I had assumed that because the Falls was the Catholic version of the Shankill, they wouldn’t have grammar schools in their streets either. I didn’t know why there were no grammar schools on the Shankill Road. No one seemed to mind anyway.

It was at the School of Music that I met Patrick Walsh. He played the violin better than me, but his voice hadn’t broken yet. While I languished in the back row of the second violins, Patrick was given solos at the front of the first violins. He went to St Malachy’s Boys Grammar School on the Antrim Road, where priests taught them maths. St Malachy’s was the nearest Catholic school to BRA, so the teachers in both establishments arranged that we would never get out of school at the same time: they were afraid, it seemed, of what would happen if we ever met each other. Patrick was from Andersonstown where the IRA ruled and the kerbs were painted green, white and orange – which was the opposite of red, white and blue.

One day, during a break from the musical massacre of one of Beethoven’s finer pieces, Patrick asked me, ‘Do you go to Belfast Royal Academy?’ His lip seemed to curl up slightly as he said the word ‘Royal’. I had never heard anyone say ‘Royal’ before without obvious deference, so I thought this was odd.

‘Aye, I go to BRA, so I do,’ I replied.

‘Are you a ... Prod?’ he pressed. Patrick seemed to have difficulty saying the word ‘Prod’, and there was that lip curl again. He seemed to be upset at me being what I was.

‘Aye,’ I replied.

‘You’re rich!’ he then squeaked, accusingly.

This was front-page news to me. I was once again con-fused. At BRA I was poor, but now at the School of Music, just like in the Upper Shankill, I was rich again. And now there was a need for yet another secret. We only met once a week at the School of Music, so I had thought that I wouldn’t need to keep any secrets – but now I realised that I would have to keep quiet about being a Shankill paperboy here too.

Patrick however knew the truth, and so he would regularly educate me on a Saturday morning. He said that his father worked at Queen’s University, and knew all about being oppressed by the Brits for hundreds of years. He said that I was an Orangeman and that as such I would be handed all the best jobs on a plate. I knew I wasn’t an Orangeman because my father kept the Sash his father wore up in the roof space, but Patrick did seem to have a point about all the best jobs, as delivering the papers for Oul’ Mac was one of the best jobs around.

One seriously savage afternoon, when all the buses were off and I was definitely going to be late for my papers, our headmaster asked an English teacher from Templepatrick (where the doctors lived) to transport a handful of us safely from the bosom of BRA to the Ballygomartin Road.

‘Where’s the Ballygomartin Road?’ asked the English teacher, to my astonishment. Okay, so it wasn’t Shakespeare, but it was only two miles up the road.

‘It’s an extension of the Shankill Road,’ replied the headmaster. It stung to hear my humble origins exposed with such authority. The English teacher’s face turned the same colour as his chalky fingers. This surprised me. I couldn’t think of a single episode of the Troubles which involved English teachers from Templepatrick being regarded as legitimate targets on the Shankill Road. In Belfast, legitimate targets were more likely to be taxi drivers and milkmen.

The English teacher looked edgy as we crammed into his spotless hatchback, which had Jane Austen on the back seat and a Radio 4 play on the radio. I definitely smelled sweat as he drove us up the Road. He was never this twitchy when teaching us about the war poets, but he put me in mind of those lines from Wilfred Owen when I noticed his ‘hanging face, like a devil’s, sick of sin’. He was only driving us up the Shankill Road: he wasn’t being gassed in the trenches! As the teacher in question transported us silently, I imagined the paperboy from his area, sitting snugly on a brand-new Chopper bike, and presenting him with a pristine copy of The Times. I was sure that his kids in Templepatrick would be getting Eleven Plus practice papers instead of the Whizzer and Chips.

The entrance to our estate was up a dark muddy lane. The mothers had been campaigning for a proper road on UTV, but it was still just a mucky path. On one side of the lane was the Girls’ Secondary School and on the other side was the Boys’ Secondary School. Most of the Shankill went there at eleven years old when they failed the Eleven Plus. Neither school was renowned for academic achievement. My mother always said it was a good thing I hadn’t failed my Eleven Plus, because I would have been ‘eaten alive in there’. My English teacher must have had similar concerns of being cannibalised as he drove up that dirty dark lane, sandwiched between two staunch secondary schools, for he proceeded with extreme caution. It was like the Doctor leaving the TARDIS for the first time, having just materialised on a strange alien planet.

As he drove along the lane slowly, the teacher at last cut the silence to say, ‘This looks like the sort of place they take you in the dark to put a bullet in your head!’

His passengers laughed instantly, but only very briefly, because he didn’t join in. We thought he was joking, but of course he wasn’t. I, for one, felt offended, and the following year, I resented the same man through every page of Pygmalion. Of course, I knew from the front page of the papers every day that people like me and Thomas were getting bullets in their heads just for being Catholics or Protestants from the wrong sort of place. But this was the sort of place I came from, this sort of place was my home, and this was the sort of place where I determinedly delivered forty-eight Belfast Telegraphs each night in the darkness.