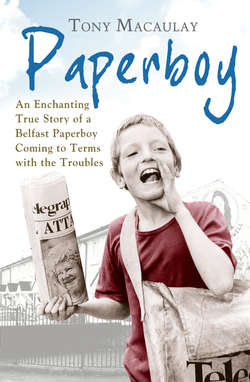

Читать книгу Paperboy: An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles - Tony Macaulay - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 3

The Belfast Crack

‘Patience is a virtue,’ said Mrs Rowing, in a gently reproach-ful manner.

The Rowings lived just around the corner from us, in the newest red-brick semis in our estate. These newer houses were basically the same as ours, but being more modern, they had no larders, smaller gardens, and the toilet and bath were in the same room. All the modernity of 1970s Shankill living was reflected in these most up-to-date of dwellings, which had central heating in some rooms and an outside water tap at the back door. The outside tap seemed to impress everyone, which I couldn’t really understand, because my granny had a toilet outside her back door and it impressed no one. Running water in your back yard was not a universally applauded amenity.

Our family home however, while it was one of the older semis, was years ahead even of the newer residences. My father had used his fitter’s skills and had already installed central heating in our house all by himself with pipes he had borrowed from the foundry. I had held the torch for him in the dark under the floorboards, as he hammered stubborn pipes into shape to keep his family warm. I was in awe of my Da’s skill and heroism. I noticed that even when he sweated big drops, he kept on working. As I held the increasingly heavy industrial torch – which my Da had also borrowed from the foundry – I distracted myself from the ache in my arm with thoughts of how people in Belfast had hidden from German bombers under floorboards just like this during the Blitz, when my father was a wee boy – not that long ago, really. At night sometimes, I had bad dreams of screaming air-raid sirens and German bombers, like in black-and-white movies, droning in the distance and then appearing in the skies above the Black Mountain to drop hundreds of bombs in our direction – one of which could be heading for your house, for all you knew. When people on the Shankill talked about the Blitz, they always mentioned Percy Street, where a bomb had landed on the air-raid shelter and killed whole families. It sounded even worse than the Troubles to me.

Looking at Mrs Rowing as she held the door open for me, I was thinking that I had never heard anyone say ‘patience is a virtue’ before, except for Robinson Crusoe on BBC 1 on a Saturday morning, as he walked around and around his island surrounded by black-and-white waves.

The other neighbours up our way didn’t talk like that. I would have been more used to something like: ‘Houl your horses, ya cheeky wee skitter!’ This was the Upper Shankill, after all. Certainly more upmarket than Lower Shankill, I was always told, but hardly Malone or Cultra, where the posh accents lived. But the Rowings were gentle and well-spoken Church of Ireland people. Mrs Rowing said her ‘ings’, collected for cancer and got a knitting magazine. In spite of their unusual name, I certainly couldn’t imagine these lovely people ever actually having a row with anyone!

Mr Rowing was my long-suffering guitar teacher, and on the night in question, I was early for my Friday evening lesson. Guitar lessons had followed a similar pattern to the advent of my paperboy career. My big brother had started first, and I simply had to follow. Then, as soon as I began, he retired. The fact that I had become old enough to engage in any activity seemed to immediately deem it inappropriate for him. This precedent would, however, later be broken when it came to drinking Harp and going to the bookies.

It was windy and cold that night as the red-brick semis of the Upper Shankill clung to the side of the Black Mountain. I had to push the Rowings’ doorbell three times instead of giving it the usual solitary ring. My fingers were still numb from folding forty-eight Belfast Telegraphs in the freezing rain, followed by a furious scrubbing to cleanse them from black ink so as to have dirt-free fingers for my guitar lesson. With my fresh and freezing fingers now plunged into my temperate duffle-coat pockets, I stamped from foot to foot in anticipation of the warmth of the Rowings’ well-kept semi. I had just finished my Friday-night paper round and safely collected the paper money for the week from all of my customers. There had been no attempted robberies by wee hoods this week: the inclement weather seemed to be more of a hindrance to their profession than it was to mine. On a cold wet Friday night with bombs in the pubs, most people stayed in. Very few of my clientele had pretended not to be in to evade my monetary demands, and so I had a warm and welcome bootful of profits.

To tell the truth, I was a little offended at the ‘patience is a virtue’ remark. It was clearly a gentle rebuke. Mrs Rowing was normally encouragingly cheerful, and my mother always said she was a lady. I was sure that patience was indeed a virtue, but I was in a hurry: it was freezing cold. Music was the fruit of my paperboy labours: from my £1.50 wages, I paid for strings, plectrums and music books, as well as 20p for this regular guitar lesson. I was keen to get out of the cold and get started. I wanted to play like Paul McCartney, so I had a lot of catching up to do.

Every week, Mrs Rowing would welcome me with a pleasant smile and usher me in to wait my turn in her well-ordered living room, complete with a cornered television. The decor was old-fashioned compared to our living room, as the Rowings weren’t as young and ‘with it’ as my parents. For a start, they wore slacks instead of flares. An ancient wind-up wooden clock ticked relentlessly on the mantelpiece and chimed every fifteen minutes: it must have been a hundred years old. The Rowings had old dark wooden furniture that reminded me of the tables and chairs that came out of my other granny’s house after my other granda died, when the Protestants were moving out of the Springfield Road. We on the other hand had the latest lava lamp on hire purchase from Gillespie & Wilson. The Rowings had delph ornaments of cocker spaniels and a copper coal bucket on the hearth; we had woodchip wallpaper and venetian blinds. They had a traditional patterned rug; we had verdant shag pile. The only old thing in our house was a bookcase my mother had bought when her numbers came up on the Premium Bonds, before I was born. It was called a ‘libranza’, and it already looked much too dated for my modern eyes.

Mr Rowing gave the guitar lessons in their sitting room. It was obviously the ‘good’ room, with a china cabinet and white lace doilies on the arms of the chairs and sofa. Opposite the sitting room was the kitchen, where Mrs Rowing lived. Although there was always a smell of freshly baked scones coming from the kitchen, I never once saw a single scone on a Friday night. Mrs Rowing was always baking, and yet there was only the two of them in the house, so I wondered who ate all the scones. I never actually got to see into Mrs Rowing’s working kitchen either, but I imagined that it contained a high fruit-scone tower piled up in the middle of her lino.

Inside the antique china cabinet in the sitting room where the lessons took place, a pair of tiny white lace baby boots rested on a well-polished glass shelf. Old and faded like Miss Havisham’s wedding dress in Great Expectations in English class, these tiny curiosities would catch my eye every week, and I wondered who the baby might have been. Maybe they had belonged to Mr Rowing when he was a wee baby, with tiny hands of less than the span of a fret. Perhaps they were Mrs Rowing’s, from a time long before her first fruit scone. Or maybe they belonged to the couple’s mysterious long-lost son, who had fled Belfast to escape from the Church of Ireland and the Troubles, to play gypsy guitar in a travelling circus in Czechoslovakia behind the Iron Curtain, where the nuclear bombs were pointing right at us.

Mr Rowing was an accomplished guitarist. On the walls of the sitting room hung faded, framed black-and-white photographs of him playing old-fashioned guitars in showbands in the fifties. Everyone’s parents had met at the dance halls in Belfast in the fifties where the showbands played. My mother and father had met at The Ritz, and I was sure Mr Rowing must have performed there. I wanted to believe that Mr Rowing had played guitar during their first dance, when a young fitter called Eric from the Springfield Road had asked an innocent seamstress called Betty from the Donegall Road for a jive. My parents had loved the showbands. When the Miami Showband were shot, my mother cried at every news bulletin and my father’s silence scared me. It was like the Troubles had taken over for them, and all the old happy times were gone for ever.

Mr Rowing looked like a young Bill Haley. He still had dark, teddy-boy hair, and he was the only customer in the whole estate who got Guitar Player magazine. Unlike me, he had big thick fingers, like sausage rolls from the Ormo Mini Shop. I assumed that playing guitar for all these years had made his fingers grow, and these sizeable and dexterous digits were perfect for switching and sustaining complicated chords. I hoped that one day my hands would become as strong and tough, so that no malevolent metal string would ever slice into them again.

A big gentle man, Mr Rowing was always encouraging and always friendly. Most men his age shouted a lot, but he never once got annoyed at my limited musical progress, tolerating my lack of practice between lessons and praising me for infinitesimal improvements. Mr Rowing seemed to understand the virtue of patience. Maybe Mrs Rowing had taught him.

The first tune I learned with Mr Rowing was, ‘Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley’. It was ancient, and country and western, and more than a bit depressing to my young ears, but it only required the ability to play two chords. The doleful lyric went as follows:

Hang down your head, Tom Dooley,

Hang down your head and cry,

Hang down your head, Tom Dooley,

Poor boy, you’re bound to die.

I played that song until my fingers stopped stinging, my family’s ears stopped smarting and my performance had become flawless. Tom Dooley died a thousand times in my bedroom, but I knew that once I had mastered this piece, Mr Rowing would, as he had promised, teach me something from the Hit Parade. I couldn’t wait. Would it be something from Top of the Pops, like ‘Maggie May’ by Rod Stewart?

But no. My next piece would be ‘Apache’ by The Shadows: an old hit from the sixties by a group with glasses that my Granny liked because ‘that lovely wee good livin’ boy, Cliff Richard, used to sing with them, so he did’. Just like Tom Dooley, I hung down my head and cried.

With every new chord I mastered, I anticipated learning a brand-new song, something groovy from the seventies. I knew I could never handle the intricacy of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ by Queen in three chords, but could Mr Rowing not at least accommodate my rock-star longings by teaching me ‘Mull of Kintyre’? In the end, I took matters into my own hands, spending all my paperboy tips one Saturday morning on the sheet music by Paul McCartney. It was half-price in the smoke-damage sale in Crymble’s music shop beside the City Hall. The Provos had tried to burn Crymble’s down, and so I feared there would be no music shops allowed in a United Ireland.

Once I had the sheet music in front of me, I taught myself ‘Mull of Kintyre’. Mr Rowing had been teaching me the basics, but now I was emerging as an artist in my own right, like Michael Jackson leaving the Jackson Five. As I played Paul McCartney’s inspiring anthem in my bedroom, I imagined I was performing it in my duffle-coat, out on a windswept Scottish hillside on the Mull of Kintyre itself, which was across the sea from Barry’s Amusements in Portrush. Earnestly poring over every chord and with every word I sang, I could see Sharon Burgess standing beside me, her hair blowing in the Celtic winds while she gazed up at me, admiring my strums, just like Linda McCartney with Paul.

Mr Rowing also promised me new songs at Christmas. I yearned to learn ‘Merry Christmas Everybody’ by Slade, but he taught me ‘Silent Night’ and ‘Away in a Manager’. Although my guitar-playing skills progressed and my ambition was limitless, sadly my repertoire never really escaped from the 1960s.

Pamela Burnside was always in just before me on a Friday night. Pamela’s parents were big fans of country and western. They had a signed photo of ‘Big T’ from Downtown Radio on their mantelpiece. Mr Burnside had a Kenny Rogers beard and a snake belt, and he sold second-hand cars down the Road. My mother said he was a real cowboy. Pamela’s mum had the longest hair on the Shankill – like Crystal Gayle – and she sang ‘Amazing Grace’ in an American accent and wore cowboy boots at the Annual Beetle Drive for Biafran babies in the church hall. The Burnsides and their small white poodle wore Union Jack stetsons on the Twelfth of July, and they wanted their daughter Pamela to be Tammy Wynette. They made her wear a suede country-and-western jacket with a fringe on the arms that got caught in the spokes of her bike. I’m fairly certain she would have preferred a Bay City Rollers T-shirt like everybody else. Anyway, she just didn’t have the kind of talent needed to be the next Tammy Wynette.

Every Friday night, as I waited my turn in Mrs Rowing’s living room, I could just about make out from the next room the muffled sound of Pamela’s desperate attempts at ‘Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley’. She rarely got the one chord change right, and I would hear Mr Rowing saying kindly, ‘Yes, that’s getting better now’ – although it clearly wasn’t.

Tom Dooley must have died a million times in Mr Rowing’s sitting room on those Friday nights. Poor Pamela always emerged from her lesson red-faced and fearful. I could tell that she felt ashamed of her poor performance and knew rightly that she was dreading the inevitable inquiry into her progress with the plectrum which awaited her at home. Pamela still couldn’t manage ‘Tom Dooley’, yet she knew only too well that her doggedly optimistic parents were already expecting her to deliver the musical complexities of ‘D-I-V-O-R-C-E’.

As I waited in the living room for my lesson, thinking up excuses for not having practised enough during the week just past, I would watch It’s a Knockout on the 1960s black-and-white push-button television. I usually longed for Pammy Wynette’s lesson to overrun so that I would get to watch an extra five minutes of Jeux Sans Frontières, as the French called it. But Mr Rowing was always merciful enough to Pamela to ensure that the lesson was not drawn out any longer than necessary.

Jeux Sans Frontières was like the Eurovision Song Contest without the songs. It was live by satellite from a football pitch in Belgium. I was astounded at how they beamed the pictures from Europe to Belfast via outer space. It was like when a Klingon from an enemy ship on the other side of a space anomaly was able to speak to Captain Kirk on the big screen on the bridge of the USS Enterprise. I was fascinated by the sound of Continental cheers, the whistles and horns and the spectacle of Germans, French and Italians and others in comical costumes, falling over each other as they fought for victory in Europe. I thought it odd that thirty years earlier these nations had been slaughtering one another. My granny still wasn’t too keen on Germans. Any mention of Germany evoked a tirade of abuse about ‘that oul’ brute, Hitler!’ According to her, he was worse than Gerry Adams. Now these former enemies were having ridiculous races in giant clown costumes to the tinny satellite echoes of hysterical laughter from Stuart Hall, the jovial presenter – and all in the name of light-entertainment television. ‘Patience is a virtue’, I thought.

I had a small Spanish guitar. It had been my first really grown-up Christmas present – that is, not from Santa. It had cost twenty weeks at 99p from the Club Book. Okay, it wasn’t a red star-shaped electric guitar like on Top of the Pops, and I couldn’t imagine Marc Bolan playing it – but I loved my guitar. It was in many ways like my first girlfriend, Sharon Burgess: it never felt cold when I embraced it or rested my chin on its shoulder.

My guitar was a honeyed yellow colour, with a simple dotted line design around the edges. It retained a lovely smell of wood and fresh varnish. At first, the strings made painful impressions on the fingers of my right hand. I was left-handed – like Paul McCartney – but we couldn’t afford an expensive left-handed guitar, so I got a right-handed one, restrung the other way round. Hence I always appeared to be playing my guitar upside down, with my plectrum guard above, rather than below, the blows of my energetic strumming. My big regrets were that I was neither Paul McCartney, nor right-handed, nor rich.

Eventually, just as the Germans were playing their Joker Card to win extra points in a raft race in gorilla suits, my absorption was interrupted by the sound of Pammy Wynette being gently escorted from the premises by an exhausted-looking Mr Rowing. Pammy generally ignored me, ever since we had fallen out at the bonfire one year, when I had said that country and western was for oul’ lads and oul’ dolls. But on this evening, as she said her apologies and goodbyes to Mr Rowing, she turned back towards me with vital information.

‘It said on Radio Luxembourg last night that the Bay City Rollers is comin’ to Belfast,’ she pronounced, with the look of superiority that could only come from being the bearer of such exclusive, fresh and earth-shattering information.

‘Brilliant!’ I exclaimed. ‘Are yousens goin’?’

‘Aye,’ Pamela responded. ‘Are yousens?”

‘Aye,’ I replied excitedly.

The word ‘yousens’ in this context referred to oneself and all of one’s friends. It was clear that most of the teenage population of the Upper Shankill would be going to this great event. Tickets would be like gold dust, and tartan material would be at a premium.

As I entered Mrs Rowing’s good room for my lesson, I dreamed of playing guitar on stage with the Rollers. It seemed promising when Mr Rowing said that he would begin to teach me a new, ‘more up-to-date’ number. Yet I was once again disappointed: it was ‘Love Me Tender’ by the pre-fat Elvis! Yet again, an old-fashioned song from the sixties that only old people liked and that most people would soon forget, instead of a modern classic, like ‘Shang-a-Lang’. However, I got my Cs and Fs and Ds in the right order, and Mr Rowing appreciated my talent so much that I got an extra fifteen minutes. I was his last student of the night, because I had to finish collecting the paper money and avoid hoods and robbers on a Friday night – and so no one was ever waiting through the final minutes of It’s a Knockout for me to finish. As a result of this fact, and Mr Rowing’s good nature and genuine enthusiasm, I often got an extra fifteen minutes for my 20 pence.

After my extended guitar lesson at the Rowings’ that windy winter night, I ran the short distance home through the spitting rain, with the tune of ‘Love Me Tender’ repeating itself irritatingly in my head. I sped past Titch McCracken, who was desperately trying to light a sly cigarette in the wind behind Mrs Patterson’s hydrangea. Overhead droned a noisy British Army helicopter, keeping an eye on West Belfast.

Before the Troubles, I had never seen a real helicopter, apart from the one that Skippy the Bush Kangaroo on UTV would alert to save a boy who had fallen down an abandoned mine shaft in Australia. But now helicopters were an ever-present whirr, looking down on us, their searchlights shining on targeted streets to illuminate any wrongdoing. This heavenly Super Trouper was in fact one of the more enjoyable experiences of 1970s Belfast – at least for me, and other boys like me. The boom of bombs pummelled the marrow in my growing bones. The deadly staccato sound of gunfire ripped at my tender heart. But the night-time sight of a helicopter searchlight rushing up your street until you were standing in quasi-daylight was as exhilarating as the rollercoaster at Barry’s on the Sunday school excursion to Bangor! It was the most exciting thing to go up our street apart from the poke man, the UDA and the Ormo Mini Shop.

On the fateful night in question, coming home from my guitar lesson, I looked up to see the searchlight flicker across the disrespectful blue-black sky. Reaching the rickety front gate of our house, I halted as the light leapt up the street towards me and all at once I was illuminated in its full, stark glare. The rays reflected off the rusty gate I had tried to paint over for 30p for the scouts during Bob-a-Job Week.

‘I hope they don’t think my Spanish guitar is a machine gun from up there!’ I suddenly thought. For a moment, I imagined a new boy having to take over my paper round the next day, delivering Belfast Telegraphs with the headline: ‘12-year-old Terrorist with Suspicious Instrument Shot Dead’. We weren’t allowed toy guns or fireworks in case they got us shot, but I had never before considered that carrying a Spanish guitar could transform me into a legitimate target. Blinded by the light and distracted by all of this catastrophising, I was unprepared for the impact.

The malicious wind blew the steel gate into my defenceless wee guitar. I heard the crack; I knew it was serious. The guitar was covered by a soft, blue pretend leather case that my aunt had bought me for my birthday. (The hard guitar cases used by professionals were too dear to be sold in the Club Book, even over sixty weeks.)This soft blue case kept the rain off my Spanish guitar, but it lacked the rigidity required to protect the vulnerable instrument from damage. I couldn’t see inside just yet, but I knew already that my precious guitar had been seriously wounded.

When I finally got indoors and saw a big crack in my guitar which ran from head to bridge, I cried. Of course, my father did his ‘fix-it’ best with glue he had borrowed from the foundry, but I had to come to terms with the fact that my guitar was permanently fractured. There was nothing I could do: it would always be split. Sadly, just like Belfast would be all my life. I yearned for things to be different, but I couldn’t envisage it any other way.

From that night on, there was a new melancholy in my rendition of ‘Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley’. Yet somewhere in my mind I still held on to thoughts of Jeux Sans Frontières and Europe and hope. And I remembered that patience is a virtue.