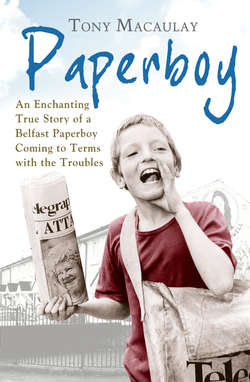

Читать книгу Paperboy: An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles - Tony Macaulay - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter 5

A Rival Arrives

I was at the top of my game, the pinnacle of my profession. I had mastered newspaper delivery. No hedge was too high, no letterbox too slim, no holiday supplement too fat and no poodle too ferocious. I had delivered through hail, hoods, bullets and barricades. My paperbag was blacker than anyone else’s, the blackest of all paperboys’ bags. I had alone survived, when all around me had been robbed or sacked, or both. Oul’ Mac even gave me eye contact.

I had achieved high levels of customer satisfaction too. One day, when I was at the doctor’s with my mother and a boil on my thigh, we met Mrs Grant, from No. 2, who always gave me a toffee-apple tip at Halloween.

‘Your Tony’s a great wee paperboy, so he is,’ she said, as she darted across the doctor’s waiting room, on her way to pick up a prescription for her Richard’s chest. The waiting room in the surgery had a shiny old wooden floor that you stared at while you waited, dreading a diagnosis of doom. It smelt of varnish and wart ointment.

‘He’s the best wee paperboy our street’s ever had!’ the generous Mrs Grant added. ‘He’s never late, there’s no oul’ cheek and he closes the gate.’ The whole waiting room stopped coughing, and looked at me admiringly.

‘Och, God love the wee crater,’ two chirpy old ladies in hats chorused in unison.

This adulation momentarily anaesthetised the pain of my throbbing boil, which had brazenly blossomed on the precise part of my thigh where my paperbag would rub. The word was out: it was official. I was a prince among paperboys. It should have been on the front page of the Belfast Telegraph itself.

But then it happened. As unforeseen as a soldier’s sudden appearance in your front garden, along came Trevor Johnston. A rival had arrived.

Known to his friends as ‘Big Jaunty’, Trevor Johnston was older than me, taller than me and cooler than me. He wore the latest brown parallel trousers with tartan turn-ups and a matching brown tank top, from the window in John Frazer’s. John Frazer’s was the bespoke tailor to the men of the Shankill, whether it was flares, parallels, platform shoes, gargantuan shirt collars or tartan scarves you were after. This emporium of 1970s style was just across the road from the wee pet shop where I got goldfish and tortoises that died, and a mere black-taxi ride down the Shankill Road. From the moment you walked through the front door of the shop and got searched for incendiary devices, you could smell the alluring richness of polyester. It was where I always spent all my Christmas tips.

It seemed that every single time I went to buy some new clothes in Frazer’s, there was Trevor Johnston, perusing the parallels. In fact, it was possible that he only left the place during bomb scares. A veritable fashion icon of the Upper Shankill, Trevor also wore a Harrington jacket with the collar turned up. I knew these were very expensive. My big brother had got a Harrington for his birthday, and it was twenty weeks at 99p from my mother’s Great Universal Club Book. When I said that I wanted one for my birthday too, my brother tore the page in question out of the Club Book and fed it to Snowball, our already overweight albino rabbit. I had to settle for a pair of faux-satin Kung Fu pyjamas instead. They were twenty weeks at 49p, but I was determined that my Harrington-jacket day would come.

When Trevor Johnston put all his chic Shankill garments together, he looked like Eric Faulkner from the Bay City Rollers, and everybody loved Eric. When I stood beside Trevor in my duffle coat and grammar-school scarf, I looked more like Brian Faulkner, the last Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. And nobody loved him.

One day, without even a five-minute telephone warning, there was Trevor Johnston, standing with the other paperboys, waiting for Oul’ Mac’s van to arrive with the bad news. Evidently, he had been headhunted at short notice. The day before, Oul’ Mac had sacked Titch McCracken, who was ginger but good at football like Geordie Best, and brilliant at twirling his band stick on the Twelfth. Poor wee Titch had been having a sly smoke in the red telephone box on our street and had inadvertently dropped a lit match into his paperbag. Minutes later, the ash of thirty-two Belly Tellys and a half-cremated paperbag on the floor of the telephone box was all that remained of Titch’s career. It had undoubtedly been the finest fire in our street since the last Eleventh boney, but Mrs Matchett across the road phoned the RUC to inform them that the IRA had carried out an incendiary attack on our telephone box. When Oul’ Mac arrived on the scene, he was so incensed that he couldn’t even speak. This was gross misconduct. Titch was so scared that he couldn’t speak either. He knew he was finished. Oul’ Mac’s disciplinary procedure involved kicking the culprit on the backside halfway up the street, until Titch ran up an entry crying, and from a distance we could hear him telling Oul’ Mac where he could stick his paper round.

So, Trevor was here to replace wee Titch. I hated the way all the girls called him ‘Big Jaunty’, with gormless smiles on their faces. Irene Maxwell – whose da raced pigeons and limped – got a Jackie and Look-in every week, and so she was something of an authority on matters of art and culture. She once made the momentous prediction that ‘them uns from Sweden that won the Eurovision Song Contest are going to be more popular than yer man Gary Glitter.’

Every time I arrived at Irene’s front gate with her weekly delivery of pop culture, she would gush, ‘Big Jaunty’s lovely, so he is. He looks like David Cassidy.’ One night, I even spotted Irene and her best friend, wee Sandra Hull (who was only six, got a Twinkle and permanently had parallel snatter tracks under her nose), following Trevor street by street on his paper round.

Sharon Burgess had never once followed me on my paper round. Living as she did half a mile away, on the other side of the Ballygomartin Road, in one of the clean council houses on the West Circular Road, Sharon never got the chance to revere me at work. Her father was Big Ronnie who riveted in the shipyard, and her mother was Wee Jean who permed pensioners in His n’ Hers beside the graveyard.

One Saturday night shortly after the arrival of Trevor Johnston on the paper-delivery scene, I bumped into Sharon at the chippy, with the usual bagful of Ulsters on my shoulder. Sharon looked lovely, with her hair flicked like the blonde one in Pan’s People on Top of the Pops.

‘Do you wanna come with me, doin’ my Ulsters?’ I asked romantically, expecting an immediately affirmative response.

‘Wise up, wee lad, I’m gettin’ a gravy chip and a pastie supper for my da, and The Two Ronnies is on our new colour TV the night!’ she retorted, devastatingly. Sharon had rejected me for a gravy chip and three old Ronnies! And so no girl had ever followed me and my Belly Tellys, just wee hoods and robbers.

Of course, Trevor Johnston looked nothing like David Cassidy. Just because he was the first wee lad in our street to get his hair feathered in His n’ Hers didn’t mean he looked like a pop star. Who would want to look like David Cassidy anyway? He was crap.

I preferred to call ‘Big Jaunty’ by his proper name: plain old-fashioned Trevor. I enjoyed that. But I also knew I had to keep well in with him, in spite of everything. Rumour had it that Trevor’s da was in the Ulster Volunteer Force, and so it was best not upset him. I noticed that Trevor was the only paperboy who never had so much as an attempted robbery. I didn’t know much about the UVF, except that they killed Catholics and beat up burglars. I still couldn’t distinguish the difference between the UVF and the UDA, but I reckoned they were a bit like Shoot and Scorcher, the two main football comics I delivered: they each had different fans, but the same goals. I concluded that they were both just IRAs for Protestants. Trevor’s da had big muscles and UVF tattoos, and wore more gold rings and necklaces than even Mrs Mac. He worked in the foundry with my father, but he seemed to have a lot more money than us. He ran the UVF drinking club down the Road, and I suspected he didn’t serve Ulster entirely as a volunteer.

Trevor’s da had led the boycott of goods from the South of Ireland in our estate. He put up posters saying: ‘Don’t Buy Free State Goods’ on the same lamp posts the children would swing on. He also promoted his campaign by marching around to everyone’s doors and telling my mother and others like her to stop buying Galtee bacon and cheese, because by doing so they were just paying for a United Ireland. Ulster was saying ‘No’ to Catholic bacon. I hadn’t realised the pigs down south were Republicans and even at the age of twelve and a half, I was slightly sceptical as to the purported impact of processed cheese on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. More importantly, I loved Galtee cheese, especially on a toasted Veda loaf from the Ormo Mini Shop, and I knew my mother snacked on it too while she was watching Coronation Street. Once a fortnight Mammy did a surreptitious shop on the Falls Road and would bring home a forbidden block of delicious Galtee from wee Theresa’s corner shop. (My mother had sewed trousers with wee Theresa in the suit factory before the Troubles. Apparently she was one of the ‘good ones’.) When my granny visited, we would hide the treacherous cheese in the fruit tray at the bottom of the fridge, underneath the oranges, of course.

When I delivered Muscle Men Monthly to Trevor’s da, there were always men with moustaches and dark glasses smoking in their living room, and I could hear Elvis records playing on the stereogram. Sometimes I wondered why so many Loyalists were Elvis fans: they always seemed more Paisley than Presley to me. There was no obvious connection between the King and the members of the UVF, apart from maybe ‘Jailhouse Rock’, and even that didn’t really make sense, because that was the young, thin Elvis, and these Protestant paramilitaries seemed to like old, fat, white cat-suit Elvis. But maybe Elvis was a Loyalist. Maybe he was doing all those gigs in Las Vegas for the Loyalist prisoners. He could have filled thousands of the collection buckets that came round our door.

One Saturday night, at our local disco, ‘the Westy’, in a lull between Suzi Quatro and Mudd, I asked Sharon Burgess secretly if she thought Trevor’s da was in the UVF. The Westy Disco was a good place to pose such a discreet question, because it was dark and noisy, and no one could hear, or see your eyes.

‘Big Jaunty’s da?’ she replied. ‘I don’t know, but Big Jaunty’s lovely, so he is, he looks like David Cassidy.’ I dropped my carton of hot peas and vinegar over the new platform shoes I had just got from John Frazer’s.

For six months, Trevor turned up on time and never thieved. He consistently delivered, and was even starting to get some eye contact from Oul’ Mac. My position was under threat. The more time I spent with Trevor, the more he irked me.

He was of course the only paperboy with no spots. He never had to use any of his tips to buy a tube of Clearasil which he would have to hide at the back of the bathroom cabinet, behind his father’s old Brylcreem jar (that had not been used since he went baldy), in case his big brother found it and accused him of wearing girl’s make-up.

I noticed, when we lined up to get the newspapers from Oul’ Mac’s van, that Trevor always smelled of Brut aftershave – and he hadn’t even started shaving! And so it came to pass that Trevor Johnston would be responsible for the most embarrassing incident of my life to date.

Spurred on by jealousy of my rival, I used some of my birthday money to proudly buy my first bottle of Brut from Boots, near the City Hall. I knew that Henry Cooper wore this aftershave, and he had knocked out Muhammed Ali. I only wanted to knock out Trevor Johnston, so I was sure it would do the trick. As I opened my first bottle of Brut, I recalled Henry Cooper in the TV adverts saying that he splashed it all over. The instructions on the bottle itself said the same thing: ‘Splash all over.’ So that night, as I was getting ready to meet Sharon Burgess, to watch her wee brother play the flute at the band parade, I did just that. By this time, Sharon and I had become an item, much to my great joy.