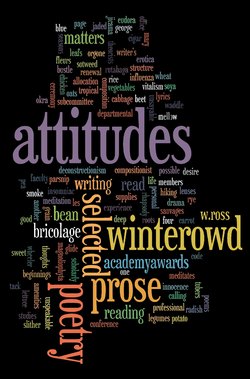

Читать книгу Attitudes - W. Ross Winterowd - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWriting Theorists Writing: Life Studies

I

We encounter the Writer in her study. She is at her Underwood typewriter, bending forward, ready to pounce, much like a leopard about to fall on a fawn, or like the favored Polish pianist, claws poised above the keys, ready to leap into an etude. The study itself is stacked floor to ceiling with typescript, so closely packed that only a narrow path from door to typing table is clear. The air is, of course, somewhat fetid; the miasma of aging paper and decades of dust are colorlessly palpable in the close atmosphere.

Following our most recent insight regarding our subject (which is, of course, writing), we ask not “What are you writing?” but “What are you doing?”

The Writer is startled, so preoccupied was she with her pre-pouncing, and she drums her fingers on the typing table, annoyed at both the interruption and the obtuse question.

“I’m making meaning!” she says testily. “What do you think I’m doing?”

The interruption has, of course, temporarily short- circuited the process of meaning-making, and the Writer uses the lacuna to expatiate on her enterprise: “I’ve been making meaning for years—even you can see that, can’t you? In fact, I’ve made so much meaning that I’m going to have to enlarge my study to hold the meaning that I intend to make in the future. Let me ask you this, pal, ‘How much meaning have you made lately?’“

Not receiving an immediate reply, the Writer suspends herself again over her Underwood, claws poised, ready to make more meaning.

Realizing that our presence impedes the meaning-making, we retire from the Writer’s study, the smell of dust with us even as we step into the fresh air.

II

We encounter the writer in his study. A Camel dangles from his lips, the smoke curling upward, bringing tears to his eyes. He writes with a fat fountain pen, and his mode of inscribing somehow reminds us of a has-been pug, sparring around the gym, punching at shadows, remembering, perhaps, the big fight that should have, but didn’t, happen.

Following our most recent insight regarding our subject (which is, of course, writing), we ask not “What are you writing?” but “What are you doing?”

The Writer looks at us, and we notice for the first time that he appears somehow to be embalmed. With a whine that is nonetheless a challenge, velvet sandpaper, he says, “What else? What’s writing for? I’m creating myself. I’ve heard all this theory shit, and I’m gonna tell you right now, get off it!”

Timidly we interject, “But we think. . . . .”

“Come on, whatya mean by that horseshirt ‘think’? If ya can’t express yourself so people can understand ya, then ya oughta shut up. Listen, I’ve been through hell and back, and what I’m doing is creating the Multiple Me, and anyone who doesn’t want to do what I’m doing is a wimp, a wimp, man, see?”Intimidated, we retire from the gymnasium odor of the Writer’s study.

III

We encounter the writer in his study. His head is all inclined to the Right, or the Left; one of his Eyes turned inward, and the other directly up to the Zenith. His outward Garments are adorned with the Figures of Suns, Moons, and Stars, interwoven with those of Fiddles, Flutes, Harps, Trumpets, Harpsichords, and many more Instruments of Musick, unknown to us in Europe.

Our writer is sputtering away with a goose quill, ink flying and blotching over vellum. His hands are black with ink, and the end of his nose is India-ink-ebony.

Following our most recent insight regarding our subject (which is, of course, writing), we ask not “What are you writing?” but “What are you doing?”

He looks up at us (we think, though we can’t be sure) and says mildly, in a Christ-like voice, “I’m discovering what I mean. My son, thou knowest that the pen leadeth to truth. My pen is my staff and my rod, and it guideth me by the still waters and sustaineth me. Join thou me in this journey and thou willst profit thy soul. Thou must learn that believing is holier than doubting.”

Moved, we sniffle a bit, wipe our eyes, and step from the smoky fragrance of incense into the cold, clear air of a long marble corridor.

IV

We encounter the writer in his study. Slouched before his computer, he is sipping a glass of sherry and is obviously not completely sober.

Following our most recent insight regarding our subject (which is, of course, writing), we ask not “What are you writing?” but “What are you doing?”

“What am I doing? you ask. I’m trying to find a rhyme for ‘okra.’ I’ve gone through two bottles of Dry Sack, but I’m stumped. Maybe I ought to abandon okra and go on with ‘cauliflower.’ Lots of rhymes for that: ‘power,’ ‘Adenauer,’ ‘bower,’ ‘cower,’ ‘shower.’ . . .

“How’s this, huh? ‘Ah, snowy, bumpy cauliflower, / Thy aroma hast the power / To make me think of earlier years / With all their joys and their tears.’ Man, I’m hot now. Just one more tetch of Dry Sack, and. . . .”

Declining the Writer’s offer of a glass of sherry, we depart his study, the cloyingly sweet odor of the wine our most vivid legacy of this visit.

V

We encounter the writer in her study, sitting in front of the screen of her computer, a generic model assembled by her engineer husband. So engrossed in her own lucubrations is she, that for several minutes she is unaware of our presence. Beside her on a paper plate lies a half-eaten hamburger, sans mustard or ketchup, pickle and onion carefully removed and sagging over the edge of the plate onto the desk.

Following our most recent insight regarding our subject (which is, of course, writing), we ask not “What are you writing?” but “What are you doing?”

Receiving no answer, we ask again, more insistently, “What are you doing?”

Startled, the Writer looks up, now aware of our presence.

“I’m composing an explication of and commentary on a text by Paul Ricoeur. Perhaps you’re familiar with this: ‘In some cases the matter to be recovered is so remote, is in a channel of thinking or feeling so alien to our own, that even a savant’s “restoration” of the environmental context is not adequate. This is always true in some degree—’“

“That was not Ricoeur,” we interrupt; “it was Burke.”

“Oh,” says the Writer. “Oh.”

We tiptoe out of her study, the aroma of cold hamburger lingering in our memories.