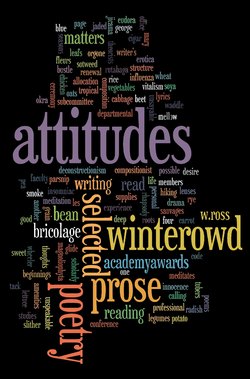

Читать книгу Attitudes - W. Ross Winterowd - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Seasons: Four Prose Lyrics

I

Under the scrub cedars, crystalline snow rots slowly away, rivulets coursing down the mountain, zigzag. A badger lumbers up the trail, pauses, looks at the boy, hisses, and lumbers on. A hawk circles high, falls from sight behind a peak, then struggles upward, a snake in its talons.

The valley below lazes in the afternoon sun, the sagebrush powdery silver, bright in the keen light against yellow sand and moist black earth. The mountains opposite are bare and dun.

The boy watches covetously as Mr. Armstrong’s bronze Packard Clipper glides silently along the ribbon of highway. In the Packard Clipper, more desirable than Mr. Holt’s black LaSalle or Mr. Johnson’s gray Buick, the boy could drive forever: Reno, San Francisco, Seattle—magic destinations.

He closes his eyes. He is on a highway to somewhere in the Packard Clipper, the girl beside him, smelling of Jergen’s lotion, her plaid skirt above her knees, her breasts rising and falling under the white blouse as she breathes. The silvery center line stretches ahead endlessly, the boy drives onward, the girl breathes quietly.

II

Like a pride of lions on the veldt, we laze on the grass in the shade of a locust tree, yawning, rolling over now and then, stretching. The heat of August afternoon ascends in shimmers from the sidewalk. In the Dutchman’s yard next door, the chickens are settled down in the shade of a lean-to, their feathers ruffled against the heat.

Don Munding rolls over on his side, props his head on his hand, and says, “Wish we had fifteen cents.”

“Yeh,” says Sonny Markowski.

“Yeh,” I say.

“Think your aunt would give us fifteen cents?” asks Don.

“Maybe,” I say.

“Then ask her for it,” says Sonny.

“Okay,” I say, but I don’t move.

Nor can I stir until the three coaches of the electric railway have passed on the tracks behind my aunt’s house. I hear the horn far away, as the train approaches the trestle, and then nearer as it crosses Redwood Road. And now the electric crackle of the trolley and the metallic thump of the wheels. A blast of the horn directly behind the house and lot sets the old cocker spaniel to howling madly. I feel the earth tremble slightly. And then the sound grows ever fainter, the horn virtually inaudible, the train gone, leaving behind an electric smell, releasing me.

“Go ask your aunt for fifteen cents,” says Sonny.

Leonine, I rise majestically, and, feline, slink around the corner of the house, into the back door, and down the basement, where my aunt is doing the laundry. She wrings the clothes through the white rubber rollers of the Maytag, and they fall into a large basket on the floor. The room smells of White King laundry soap, as does my aunt, always.

“C’n I have fifteen cents?” I ask her, without preliminaries.

“Why fifteen cents?” she asks.

“Cause Sonny and Don are out there, too,” I reply.

My aunt, a soft touch, but a thoroughgoing Puritan nonetheless, tells me, “You can have fifteen cents if you’ll help me hang the laundry out to dry.”

The last pair of Mormon garments through the wringer, my aunt puts on her large straw hat with the pink ribbon around the crown, and we lug the basket, she on one handle and I on the other, to the yard and pin each item to the wires that stretch from pole to pole perhaps forty feet. The laundry hangs sodden in the heat, the sagging mid-section of the wires held up by portable forked poles.

When I return to the shade of the locust tree, Sonny and Don regard me through half-closed eyes, but since I don’t flop on the lawn, they know that I have the fifteen cents, and they lazily, in slow motion, get to their feet. We walk across the road to the two-pump service station (regular and ethyl), our Keds scrunching the gravel of the apron. Mr. Maw sits in an old swivel chair in front of the small frame building. Barely moving, he nods assent for us to enter, and we go through the open door. On shelves to our left, cans of Quaker State motor oil. On the back-wall shelves, loaves of Wonder Bread, packages of Fisher doughnuts, and cans: Pierce’s pork and beans, Spam, Del Monte salmon. To our right, a glass display case (with jawbreakers, Doughboys, Tootsie Rolls, licorice cigars, marshmallow bananas, bubble gum, small wax bottles filled with punch) and a noisy freezer, chug, chugging. I open one lid of the freezer, take out three Fudgesicles, give one to Don and one to Sonny, and, leaving, place three nickels in Mr. Maw’s outstretched hand. No words have been exchanged during the whole transaction.

As we are leaving the station, a shining new black Terraplane skids slightly on the gravel as it pulls up to the pumps.

We cross the road, settle ourselves in the shade under the locust, remove the paper bags from the Fudgesicles, and begin voluptuously to lick at the rapidly melting, watery ice cream.

III

Two odors, aromas, smells. Frying pork chops and burning leaves—one richly oleaginous, the other spicily acrid.

In the almost dark of a mid-October six o’clock, the entry light and the windows of the red-brick apartment house glow through the chilly haze. The poplars between the sidewalk and the curb are bare, their brittle gold and brown leaves filling the gutter and lying in puddles on the lawn. Parked at the curb is a shining new Hudson Hornet, silver and gray, sleek, streamlined. A radio somewhere in the building, turned too high (or at least high enough to be heard on the sidewalk), plays “On the Steppes of Central Asia.”

The building is two-story, with a front door of oval plate-glass set in heavy, much-varnished hardwood, with a brass loop handle and thumb-trigger.

The carpeting in the hall is worn maroon, with large, stylized flowers in green and yellow. The chipped paint on the wainscoting is off-white, an almost ashy gray. The doors to the apartments are the same much-varnished hardwood as the front door, and each has a brass number: 1, 3, 5, 7, 2, 4, 6, 8. “On the Steppes of Central Asia” is now virtually a roar, but then sudden silence: the radio has been snapped off. The smell of porkchops frying is almost palpable.

Before the door of apartment 3 lies the evening paper. The door opens, and a woman in a cotton housedress (white, printed with violets) stoops, picks up the paper, and glances momentarily down the hall. She has the classic, almost masculine face of a Venus de Milo; her hair is drawn into a bun at the back of her neck; her breasts are full, and her hips are broad and capable.

The hall is lighted by three meager frosted-glass, one-bulb fixtures spaced down the ceiling, and in the light, almost as if from candles or lanterns, the aura is golden, mellow, with the maroon of the carpet, the rich smell of the porkchops, the dark wood of the doors, and the many-layered paint on the woodwork. A woman’s gentle laugh is barely audible. And then a metallic clang, perhaps a pan that had fallen, and a man’s voice: “Damn!”

The radio plays again, now softly: “In a Persian Market.”

A woman appears beyond the glass of the front door and, holding a large brown paper sack in one arm, opens the door and enters the hall. Her tan plaid skirt stops just above her knees. The coat, with its fur collar, is chocolate brown. Her brown hair tumbles from beneath a brown tam. Her shoes are spike-heel black patent leather. She glances down the hall and then hurries up the stairs, which creak slightly with her every step. Behind her hovers the aroma of cosmetics, face powder, and perfume.

Throughout the city, brick apartment houses: sooty yellow or deep red. At six o’clock of an October evening, they glow at entryways and windows. They smell of frying meat. Their halls are musty and dimly lighted. From behind the doors come muted sounds of voices.

In the chill haze of an October evening, brick apartment houses. Mystery and romance.

IV

A new Rambler American, pure white, is parked beside the heaps of plowed, grimy snow. Deep-sunk footprints lead across the snowfield to the river, a quarter-mile from the blacktop road pied with glazes of milky ice.

The river runs green and swift between the snow and snow, here and there a foamy white where a rock breaks the current into eddies. Three stark and hoary trees stand lacy beyond the far bank.

The river gurgles, sloshes around the rocky point where the fisherman stands. He is insulated, puffed with down and kapok, his boots rubberized, his cap synthetic fur with earflaps pulled all the way down.

In his left, heavily-gloved hand he holds his pole; the right, ungloved, he tucks into his left armpit.

The pole jerks. He sets the hook. Another jerk, another sharp pull upward. A third jerk, another sharp twitch. He almost reluctantly pulls his hand from the warmth of his armpit and reels the catch in. The pole bends almost double and is alive with the struggle of the fish. The first breaks water, and he works it as he hauls the second and the third toward the surface. Now all three are moving with the current, strangely passive as though they’ve given up and, unlike trout, are ready for the net. But no such dignity as nets for whitefish, and he cranes them up, the rod almost an “O” with the weight of three foot-long fish.

With long-nose pliers, he unhooks each one and throws it back into the snow, where a heap of whitefish is growing, maybe twenty or thirty. From a plastic tube, with his right hand, he extracts a maggot, fat, white, but almost inert in the cold, and puts it on one hook. He puts a second maggot on the next hook, and a third maggot on the final hook. He puts his fingers to his nose and smells the putrid flesh in which the maggots were nurtured, the scent of death.

He casts the rig out and waits for the jerk-jerk-jerk of the struggling fish.