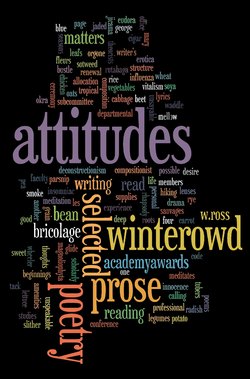

Читать книгу Attitudes - W. Ross Winterowd - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIII. Academy Awards

1. Chicken Cacciatore

Professor J. Melongaster Druse had married badly. In fact, his wife was a bowler. Every Wednesday she donned her crimson polyester shirt (blazoned in gold on the back with “Happy’s Hamburger Haven,” her team’s sponsor), lugged her ball and shoes (in a tooled leather bag) to the ungainly red Buick parked in the driveway of the Druse residence, and made her lumbering way to the lanes.

Druse had watched his neighbor, Cynthia Golden, depart for her sets at the Newport Racquet Club, golden Cynthia in her tennis whites (the decorously provocative short skirt revealing just a callipygian glimpse beneath the lacy line of immaculate panties), skipping to her Mercedes convertible, waving gaily at her neighbors, and gliding off for a morning of sociable recreation, followed, no doubt, by lunch at the club.

Tanned, manicured, and perfumed, fastidious, meticulous, and chic, lithe graceful and girlish, Cynthia was overtaking middle age with purring, dignified equanimity, and when Mel Druse saw her, he warmed, not with lust, but with envy of Dr. Greg Golden, who had not only Cynthia, but also the cachet of being an enormously successful neurosurgeon (tooling about in a silver Porsche with the personalized license plate “Brain 1”). Inevitably, Greg was imperially slim and crowned with a glorious, wavy, carefully tended silver mane. Mel, of course, was short, pudgy, and bald. Greg and Cynthia were, naturally, the social lions of the neighborhood, much sought after as guests; the annual Halloween brunch at the Goldens’ was the neighborhood’s most festive and eagerly awaited occasion. Whether hosting or guesting, Greg and Cynthia were unfailingly considerate and witty, paying alert attention during conversations, listening patiently to accounts of lawns, pool filter systems, golf games, and children gone awry or aright.

In short, Greg and Cynthia Golden were everything that residents of their very upper-middle-class neighborhood ought to be. Greg even played bassoon in the Orange County Doctor’s Symphony, and Cynthia was, as might be expected, an active member of the Museum of Art board.

All of this glowing perfection gnawed persistently at Mel’s peace of mind. So much glamour and romance created insuperable odds against a literary scholar married to a bowler. Who, after all, would not snicker if Mel recounted his adventures in putting together his book on the fop in Restoration drama: poking about dusty libraries and pecking out ideas on a Dell laptop hardly compared with the tense hum and beepbeepbeeping of the operating room; being mentioned in the Times Literary Supplement hardly ranked, among the laity, with being featured in the “Modern Living” section of the Sunday paper, as the Goldens had been. And then there was the vibrant tennis player versus the bowler.

The neighborhood was eclectically expensive, Elizabethan bungalows elbow to elbow with French chateaux, and ranch styles rambling about oversize yards, with split rail fences and wagon wheel motifs. Palm trees and pines cohabited peacefully, but had not gone quite so far as miscegenation.

It was a residential area in which the few churches resembled medical complexes, the medical complexes looked like groupings of expensive cottages, the lawns were as uniformly pruned and verdant as Astro Turf.

The dogs were standard poodles, Irish wolfhounds, Weimaraners, and Dobermans; the cars were Cadillacs, Mercedes, Jaguars, and Porsches. (One neighbor who drove a Rolls Royce was the object of general scorn. Such conspicuous consumption was vulgar and violated the unspoken norms of the neighborhood. Rolls Royces belonged in Beverly Hills, not Huntington Beach.)

It goes without saying that the Druses had a source of income other than Mel’s salary; the neighborhood, with its houses ranging upwards of two million dollars, was for bankers, auto dealers, corporation lawyers, proprietors of chain dentistry enterprises, and neurosurgeons, not college professors. In fact, had they chosen to do so, Mel and Bobby could have lived in a much tonier neighborhood than this one, could, in fact, have afforded the very ritziest, for she was the heiress of a very large fortune inherited from her late husband, Bert Redd, the magnate who had owned a great portion of the casino business and less savory enterprises in Nevada. When he was well into his seventies and had divested himself of his fourth wife, Bert saw Bobby, in ostrich feathers and sequins, on the stage at the Xanadu, Bert’s most opulent casino, where she was dancing to support herself while she worked on a master’s in computer science at UNLV. It was love at first sight on both sides. After a mad weekend of dining and dancing, and after Bert slipped a ten-carat diamond ring on Bobby’s finger and draped her with a diamond and emerald necklace, they were married on Monday in The Little Chapel of Eternal Bliss, serenaded before and after the ceremony by an Elvis impersonator. After one year of rapidly waning marital bliss, Bert went to that Big Casino in the Sky, and Bobby was left with all of the loot.

The tale of how Mel and Bobby got together is the stuff of romance novels or TV soap operas.

Mel, a bachelor, had just been promoted to associate professor with tenure, having cleared the hurdle at which at least three-fourths of assistant professors fall. He was elated, and his whole demeanor changed, from unctuous pliability to smug aloofness. As Professor Pottle Tinker put it, “Hrumph . . . Mel seems to be . . . hrumph . . . practicing to become . . . hrumph . . . a dean.”

As a reward for tenure well-won, Mel pointed his Toyota Corolla northward on I-15, toward Las Vegas, where he planned a weekend of madcap diversion, release from the serious business of studying and professing Restoration literature.

On Saturday evening, he was grazing at the all-you-can eat buffet in the Xanadu. Walking toward a table, he slipped and splattered a woman at a table with chicken cacciatore and caesar salad. He grabbed her napkin from her lap and began wiping the front of her white blouse.

“I’m sorry. I slipped on a wet spot on the floor.”

“Get your hands off me, pal!” said the woman.

When Mel kept wiping, the woman gave him a solid one to the jaw, and he stumbled backward onto an adjacent table, where a couple had deposited a tray overstocked with dessert delicacies, all topped with globs of soft ice cream.

“Oh my goodness!” gasped the lady. “You asshole,” shouted the man.

At which point two security guards appeared, one tall and spectrally thin, the other short with a massive overhang above his belt. Each took one of Mel’s arms, securing him, and the tall guard, addressing the woman with the bespattered blouse, asked, “Is this man annoying you, Mrs. Redd?”

“Nah. He tripped in a puddle on the floor. Let ‘im go.” Then to Mel: “Come on. I’ll buy you a drink.”

From: Druse@cdu.edu

To: JMoss@mit.edu

Nov. 7, 2000. I just voted for George W. Bush. The last debate convinced me. Gore is one of those left-wing big spenders. Bush might have his faults, but at least he won’t pick our pockets to pay for half-baked socialist projects.

Memorable day. The department just voted to give tenure to Faustino Ajaia on the basis of a first novel: The Gents in Pink. Of course, I had to read this junk about cross-dressers. In our day, Jesse, you didn’t get tenure on the basis of one novel. Of course, Ajaia is a PC shoo in: Hispanic author, sexually liberated subject. Frankly, I don’t think writing of any kind has a place in an English department.

Bobby and I are thinking about coming East over Christmas break. If we do travel, we look forward to seeing you. Those years of grad school at Wisconsin were great, weren’t they?

From: JMoss@mit.edu

To: Druse@cdu.edu

I can’t believe that you voted for Bush. God, the man can’t even express his ideas (if he really has any). “Families is where our nation finds hope, where wings take dream.” Wow! If he would say nuclear rather than nucular, there’d be some hope. I’ve always told my students that muddled language is a sure sign of muddled thought. Well, we’ll see what happens. Frankly, I think that Bush is an irresponsible jerk.

I’m sorry to tell you that Martha and I will be in France over the Christmas break. Another time maybe.

2. Peppermint; or Heart of Darkness

Late afternoon. Professor J. Melongaster Druse sat at his desk, killing time before leaving to attend the annual departmental cocktail party, looking forward to a few minutes of inert solitude, but on this Friday surcease from the storm and stress of a professor’s duties was not to be.

A knock on the door of his office. His response. Mr. Garth Timmins entered and took a seat, forcing Druse to pull himself together and refocus. Timmins, in his snowy white cheerleader uniform, a large purple C in chenille on his chest, apparently found it as difficult to leave his rah-rah attitude and bearing behind on the playing field as it was for Druse to rally the expected professional courtesy and attention. The clash in moods—Garth’s sunlamp cheerfulness and Druse’s twilit dourness—created emotional smog that hung between the student and his professor.

“What can I do for you?” asked the professor, anxious to get the meeting over with.

“You going to the game tomorrow, Professor Druse?” In his Speech 101 class, Garth had learned that conversations begin most productively with any point of common interest between the parties involved. This bit of wisdom, filed away in both his memory and his class notes, was perhaps the most useful and exciting learning experience in his three years at the university.

“I must confess, Mr. Timmins, the only thing that interests me less than football is baseball. Once the groundskeepers have mowed the lawn and painted the white stripes, the excitement’s over for me.”

Timmins laughed his professional cheerleader’s laugh and said, “Gee, that’s a good one, Professor Druse. I’ll remember that one to tell the team,” and he glanced at his Rolex wristwatch, his smile—the model specially designed for English profs, those strange birds who were for some inexplicable reason necessary for a well-rounded education, which, of course, Timmins wanted to get since that was what he had been told his father was paying for, and if nothing else, the son believed in value received—his smile was frozen on his tanned visage, and his golden hair was tousled just enough to look completely natural, an effect that was a constant preoccupation for the young man.

Druse assessed Timmins. He was a perfect representative of the university’s student body, those golden youths whose destiny was a home in Beverly Hills, a Mexican or black cleaning lady (“almost one of the family”), a Mercedes or Jaguar, a ski trip to Utah or even Switzerland in February—two children attending private school, season tickets for one “culture” series (the symphony, the theater), membership in a tennis club, and the deep-felt security that the proper values and accomplishments confer.

“Say, Professor, you know you told us to talk to you about term papers, and I have this idea I’d like to bounce off you. You know, the fops in Restoration comedy—I mean you’ve talked a lot about them—and, you know, I was thinking: they’re all gay.”

“Indeed? And what led you, Mr. Timmins, to that conclusion?”

“Well, you know, they dress in lace and all that stuff—and the way they talk, you know.”

“Aren’t you, Mr. Timmins, simply projecting modern attitudes and your own repugnance for homosexuality onto works of literature from an age in which norms of behavior were quite different from ours? Aren’t you, after all, reading too much into the comedies?”

“Well, I’ll tell you, Professor Druse, I don’t know about Congreve or any of those dudes, but I know that us gays aren’t ashamed of ourselves anymore.”

“You say ‘we gays.’ What might you mean by that?”

“I mean I’m gay.”

“Well, I don’t suppose that’s anything to be ashamed of,” responded Druse, after a significant pause during which he formed a new conception of Garth Timmins, the old image—home in the right neighborhood, two children in private school, the proper kind of wife—having been shattered. Now Garth was dancing with another man in a disco and going to bath houses. Druse was even a bit revolted by the possibility that Garth was already infected with herpes or AIDS.

“I’m not ashamed. I’m proud. Danny McLatchy, the tailback, he’s gay too. And several fellows on the team are switch hitters. And let me tell you, I happen to know that two of song girls are lesbians.”

“Enough! Quite enough!” Druse was genuinely peeved. “I have no desire to discuss the sexual aberrations of our students. If you feel a need to talk about such matters, you should go to the counseling service or the chaplain.”

Timmins’ smile vanished. He leaned forward, glaring at Druse. “I guess you don’t like queers, do you, Prof? We’re either crazy or sinners—or both—so we should go to the school shrink or the chaplain and get ourselves straightened out. I’ll bet you think blacks should be kept in their place, too.”

Druse chose his well-rehearsed role as the icily aloof scholar-mentor. “Mr. Timmins, I haven’t the slightest interest in any of my students’ sexual preferences or habits. What you do in your own bedroom is your business. However, I don’t allow sex either in my office or in my classrooms.”

Timmins leaped at the opportunity. “Oh, I don’t want to have sex in your office, let alone in your classroom, Professor. All I want is freedom and equality.”

“You’re not funny at all, Mr. Timmins. In fact, you’re downright impertinent. Perhaps you’d better come back at a later time, after you have thought about your manners, to discuss your term paper.”

“Look, Prof, tuition at this place is astronomical. Us students pay your salary.”

Druse’s tone was lethal, prussic acid. “Leave my office immediately. And don’t come back. Drop my course. I never want to see you again. Out! Out! Out!”

Timmins scurried out the door of the office.

“These assholes are barbarians,” muttered Druse. “What a bunch of shitheads. Why couldn’t I have got a job at Johns Hopkins, where I wouldn’t have to put up with these philistines? A homofuckingsexual, probably buggering the goddamn quarterback, or the quarterback buggering him. Christ, what a filthy, rotten mess. And I’m stuck. I can’t get out.”

Druse took a deep breath. The flash of Timmins’ ass in the skintight white polyester flannels, when he flounced out the door of the office, had left the professor with a distressing thought. He had another twenty years before retirement, two decades of the likes of Garth Timmins. Graduate students worked on dissertations under the direction of Alex Hamilton, whose whining voice drove Druse nuts; Potty Tinker had graduate students in spite of the perpetual “hrumph . . . hrumph” that made Tinker’s lectures virtually incoherent; Max Schinken had to deny requests to serve on graduate committees. But Druse had no graduate-student following; hence, he was incomplete, not achieving the status that adulation from advanced students brings about. Mel shook his head sadly. Twenty years of Garth Timmins.

Druse took Mr. Sammler’s Planet from his bookshelf and prepared, this third try, to get through the masterpiece, but he had just opened the book to the first page when the door to his office burst open, and Garth Timmins stood defiantly before him.

“I want to inform you, Professor Homophobe, that I just reported you to Dr. Burden, and Monday I’m going to Dean Amore. There are laws against people like you.”

Before Druse, astounded and trembling, could respond, Timmins slammed out of his office—the dirty little queer sonofabitch, the goddamn fruit. He probably goes around smelling bicycle seats.

Now nothing could rescue the remainder of the waning day, and the only immediate prospect before Professor J. Melongaster Druse was a two-hour hiatus prior to his departure for Adam Adam’s place, where he would meet Bobby, his wife, to endure the rite of the annual departmental cocktail party and get-together. A bleak two hours those would be.

He listened to the sound of a jet overhead, followed by the whack-whack of a helicopter. From somewhere he heard a shrill, brief laugh. Uninterestedly he glanced at the mail on his desk before him.

As he was about to open the first envelope, his phone rang. “ . . . Just catching up on a little work before I go to the party. . . . Nothing important. I’ll be right down.”

Warren Burden, department chair, had asked to talk with Druse. What a pain in the ass. He knew what the subject of this interview would be, and he tensed his system for the walk down the hall and the ordeal of putting up with Warren’s namby-pamby remonstrances regarding the Garth Timmins episode.

The outer office was deserted, and Warren’s door was open. As Druse entered, Warren said, “Sitzen Sie sich. I mean, setzt euch. Assiez vous. I’ve got to run down the hall for a minute.”

Why didn’t the ostentatious jerk just say, “Have a seat”? Druse plunked into a chair by the coffee table, waiting for Warren Burden to reappear. As if in a trance, a deep preconscious state, he stared at an African fetish on the coffee table, an ojet d’art that Burden had brought back from his guest professorship in Nigeria. It was about two feet high, in dark wood, glossy and suave. It was a woman, with hair dressed high, like a melon-shaped dome. At the moment, she seemed like one of his soul’s intimates. Her body was long and elegant, her face was crushed tiny like a beetle’s, she had rows of round heavy collars, like a column of quoits, on her neck. He stared at her: her astonishing cultured elegance, her diminished, beetle face, the astounding long elegant body, on short, ugly legs, with such protruberant buttocks, so weighty and unexpected below her slim long loins.

So engrossed was Druse that Burden entered and settled at the desk without disturbing the trance.

“Uh, Mel, are you with me . . . or in Africa?”

“Oh, Warren. I was in Africa, I guess. I’ve seen that hideous figure a thousand times, but it’s new, different every time I look at it. Deep down, I must be primitive. I’m attracted to that horrible thing. If it comes up missing, you can look for it in my office.”

“You should go to the ‘Dark Continent.’ It’s darker now, I think, than when Conrad was there. The old tribes, the old rites, the old ways—they’re dying out slowly, but they still exist. That Dark Goddess there still reigns. The old ways, the savage ways are just a few steps outside of town. Oh yes, Kurtz is still in Africa, but he’s no longer at a station far up the river. He’s in Lagos—where the lights come on and go off according to the whims of . . . of . . . well, probably, of that Dark Goddess there. And Kurtz is chauffeured through impossibly filthy streets, thudding into potholes, in his Mercedes. He does a little banking, a bit of smuggling; it’s even said that he can sell you a slave if you’re in the right place and have the right price.”

“Yes, I’d like to go to Africa,” said Mel. “We’ve been to the Greek Islands, but they’re so tame, so familiar. I mean our family tree goes right back to the Greeks and the Romans, but there haven’t really been any Africans in our cultural woodpile. I mean compare Hitler with Idi Amin: the civilized barbarian and the barbaric barbarian, Hitler worshipping Wotan, Idi praying to our Dark Goddess here. You should bring this goddess to the cocktail party tonight. Maybe she’d elicit a refreshing strain of barbaric savagery from our colleagues.”

There was a silent pause.

“So,” said Warren, “we have a little problem with Garth Timmins, don’t we?”

“No problem that I can see,” said Mel, rallying his full reserve of inner strength.

“Between you and me, Mel, Timmins is a problem child. I wish he’d stay in the School of Business Administration where he belongs. But he’s ours for his general education requirements in the humanities, and we’ve got to deal with him. He’s pretty upset about his interview with you.”

“And I’m pretty upset about his interview with me.”

“I don’t doubt that in the least. He’s an annoying guy. I had to put up with him in my class last semester.”

“We ought to kick him out of the university. I mean the way he came on to me was unforgivable. I couldn’t care less about his sex life. I told him that. He uses his deviation as an excuse for being a goof-off. And you can’t imagine how arrogant he is.”

“I’ve checked his record,” said Warren in a conciliatory tone. “He had a B-minus average. You aren’t thinking of flunking him or anything like that, are you? This is a delicate matter. First of all, there’s Timmins’ charge of discrimination, and you know what that means nowadays. It can be dynamite. How’d you like to have all the gays in West Hollywood picketing the English Department? And then there’s Timmins senior. I happen to know there’s bad blood between father and son—over the gay business, you know—but senior, on the other hand, is very proud of Garth’s position as cheerleader, and isn’t he president of his frat? Anyway, there’s big money involved. Mr. Timmins has hinted to Dean Amore that he’s ready to make a substantial contribution toward the new science complex. We wouldn’t want to be parties to losing that grub stake, would we?”

“Well, so much for Garth Timmins” said Mel. “I need to talk to you about my schedule. Damn it, Warren, you’ve got me down for another section of composition. Look, I’m a senior person, not a lousy assistant professor or graduate teaching fellow. I asked to teach the seminar in Restoration drama.”

“Mel, as far as I’m concerned, I’d like to give every faculty member the classes that he or she wants. But you know that Dean Amore has been looking us over very carefully. To tell you the truth, the last time you taught the Restoration seminar, you had only three students, and that’s just bad economics from the standpoint of manpower invested.”

“My god, Warren, you sound like that Donald Trump—or like Jack Welch. We’re not a real estate empire. We don’t manufacture jet engines. We’re humanists. Teachers. Literary scholars. Of course, Amore probably thinks he’s the Jack Welch of higher education.”

“Lester is a tough manager, but maybe that’s what this university has needed. Maybe we should stop indulging our hobbies.”

“Now that’s a shitty thing to say. That’s just plain rotten. So Restoration literature is just a little hobby, huh? Not worth the time of serious thinkers. What about your field? Is that just an unnecessary hobby, too? I haven’t seen Beowulf on ‘Masterpiece Theater’ yet.” Mel was red-faced, and spit bubbles had formed at the corners of his mouth.

“Calm down. Calm down. Here, have a peppermint candy. I’ll talk to Dean Amore. Don’t get excited until we see what the administration is willing to do.”

“Fuck the administration. And fuck you, too,” shouted Mel. Grasping the African goddess, he shouted grimly, “I hate peppermint.”

From: Burden@cdu.edu

To: Rodby@Andrew.cmu.edu

Dec. 9, 2000. Well, the fat’s in the fire. The Supreme Court in its infinite wisdom has stopped the hand recounts of the Florida ballots.

I’m about to have a conference with my colleague Mel Druse—who, by the way, is a Bush supporter. The jerk, he just had a big set-to with one of our students, who happens to be the son of a major donor to the university and who happens also to be gay. Mel gets as furious as Donald Duck in the old cartoons, and he has the judgment and subtlety of a pit bull. If I can get through that discussion without Mel having a fit, then I have to tell him that he’s scheduled for a section of advanced composition next semester. May the good Lord protect me from the wrath of a literary gent demeaned.

I’ll see you at the big meeting in a couple of weeks. The drinks will be on me.

From: Rodby@andrew.cmu.edu

To: Burden@cdu.edu

I’ve run across Mel Druse here and there at meetings. He always seems very intense, humorless. He can’t have a sense of humor, or he’d laugh at Bush rather than support him. About a month ago, Bush stumbled into a characterization of himself. You remember he said, “They misunderestimate me.”

From my point of view, anyone who has anything good to say about that guy misunderestimates him.

Poor Mel, being faced with the horror of teaching advanced composition. I remember last year at the convention, he read a paper on Vanbrugh. Is he the only person in the world who’s now interested in Vanbrugh? Yeh, I think Mel Druse must be one of your many problems

See you soon.

3. Falafel; or, The Education of Bobby Druse

Hearing her voice in the hall, Professor Alexander (“Alex”) Hamilton (“Ham”), said, “Here she comes, i’ faith, full sail, with her fan spread and her streamers out, and her husband for a tender; ha, no, I cry for mercy.”

Her topgallant billowing, Professor Peggy O’Neil sailed into the room, gave a general “Hi, everyone!” and continued the monologue that had preceded her. “I thought my last book would never get out. I’ll never again submit anything to Yale. You can’t imagine how klutzy they are. I mean that editor is a real nitpicker. But, thank God, I have the first bound copy now. I brought it with me. Here it is. The long-awaited book.” And on the coffee table she triumphantly placed A Pound of Mixed Nuts: Insanity and Modern Poetry. “What a hassle to get here. Alvin was late getting home from the lab. A student called me, and I just couldn’t get rid of him. He talked on and on. I’m starved. Is there anything to eat? Did all of you see the article about Stanley Fish in Newsweek? Alvin and I don’t subscribe to Newsweek, but a student brought it to me. Fish is a real fraud, you know. All this stuff about reader response. I bet he couldn’t even pass our doctoral exams. I sometimes wonder if he’s read Shakespeare. Speaking of Shakespeare, who’s going to teach the undergraduate survey next semester? Is Warren here? I’d like to talk with him about the undergraduate courses. Where’s Warren? Alvin, get me a drink. Is there anything to eat? I’m starved.”

Mel and Bobby entered the room. Catching sight of them, Professor Peggy O’Neil, from her central position, greeted them: “Oh, you. Hi. Mel, have you been sick? You look terrible.”

“I hope Warren comes tonight. We simply must talk to him about the undergraduate program. Those people don’t know as much as I did when I got out of high school. The other day I found a senior who hadn’t read ‘Ash Wednesday.’ Now that’s a shame. Maybe we ought to raise our admission standards. Don’t the high schools give students any preparation? After all, shouldn’t we be able to expect that our students would know at least the anthology kind of stuff? I don’t mean the hard stuff like Finnegan’s Wake, but everyone—and I mean everyone—should have read Portrait of the Artist. I mean, after all, how can you claim to understand the twenty-first century if you haven’t read Portrait of the Artist? I’m hungry. Is there anything to eat? Alvin, where’s my drink?”

Professor Peggy O’Neil now had a fleet of tenders; besides Alvin, there were Mel and Bobby, Alex Hamilton, Bertha Bankopf, Merrill Woodsman, the utility socialites Herb and Nancy Grupp, and more were expected, for this was the annual end-of-semester department get-together and cocktail party.

“ . . . I’m starved. Isn’t there anything to

eat? . . .”

Kate Reese entered the room, pausing to look about and get her bearings and then moving toward the galaxy clustered about Peggy O’Neil. Alex Hamilton put his arm around her waist, and she pecked him on the cheek. Pottle Tinker patted her on the shoulder and greeted her: “I’m . . . hrumph . . . happy to see you. I think . . . hrumph . . . you’ve been . . . hrumph . . . avoiding me.” Kendall Turing kissed her on her ear when she turned her head.

Kate was now the party’s cynosure, and Peggy O’Neil was talking largely to herself.

“ . . . and I simply told him, ‘Hillis, you, Geoffrey and Harold live in a dream world. I mean, you don’t know. . . . ‘“

The room was filling rapidly. Guests entered two-by-two, three-by-three, and four-by-four. With each set of arrivals, the decibel level rose perceptibly, a cacophonous cocktail symphony.

“ . . . they deal with the cream of crop. The best students. Is there anything to eat? I’m starved. . . .”

The host, Professor Adam Adam, came to the rescue. To save Professor Peggy O’Neil from the horrors of inanition, he offered her a tray of golden spheres and a bowl of sour cream.

“I just don’t understand why—What’s that?” asked Peggy O’Neil, pausing long enough to notice the proffered provender.

“It’s falafel,” said a dour Professor Adam Adam.

“Fa- what?” inquired Peggy O’Neil.

“Fa-lafel,” said Adam.

“What’s falafel?” asked O’Neil.

“It’s a Mideastern dish. Actually, deep-fried camel dung,” explained Adam.

“Oh!” said a startled Peggy O’Neil. “Oh, you’re kidding.” And she giggled. “Seriously, what is it?”

“Try it, and see if you like it. Take one and dip it in the sour cream.”

Peggy obeyed. “Hm, not bad.” she said. “Not bad at all.” She took another, dipped it, shoved it in her mouth, and continued: “But I want to tell you about my new project. I’m very very excited. . . .”

Isolated in a corner with Bobby, grumbling Mel muttered, “What a pain in the ass. I don’t know why you insisted that we come to this party.”

“You know,” said Bobby, “you really look like hell tonight. What’s wrong? Your hand’s shaking so badly that you’ve slopped your drink. Have a couple more and you’ll settle down. Come on. Why don’t you try to enjoy yourself? Let’s mingle and talk to people. There are Jerry and Bridget.”

Across the room from the Druses, Professor Gerald Gelb was talking earnestly with Assistant Professor Bridget Heiman. When Bobby and Mel edged into the territory staked out by this pair, Gelb, alternately stroking his beard and raking his fingers through his long hair, was saying, “You understand I don’t believe in confrontations, not at all. I’d rather talk to people in private, as it were. A conversation over lunch can do more than all the open meetings in the world. But I think it’s time that someone told Warren the way of the world—the way of our little departmental world, that is. He’s out of touch with reality.”

“So who’d you want to be chair of the department? Waldo Clemens and his goddamn pipe? Or how about Potty Tinker? All we’d ever get out of him is ‘Hrumph, hrumph.’”

“Now, Mel,” conciliated Jerry Gelb, “I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with Warren. Not a bit of it. I just think we should talk to him about the situation. That’s all. I’m on his side, of course. You know that.”

“ . . . but just wait until you see my article in Critical Inquiry. Alvin, my glass is empty. . . .”

The galaxies in Professor Adam Adam’s living room were rearranging themselves. The cluster of bodies around pulsar Kate Reese was diminishing, the center of gravity shifting toward the constellation formed by Mel, Bobby, Jerry, and Bridget.

Assistant Professor Merrill Woodsman and his companion, Mrs. Bertha Bankopf, joined the growing circle around Bobby and Mel.

“Mrs. Druse,” said Jerry Gelb, “I don’t think you know Merry Woodsman.”

“I’m happy to meet you, Mary,” said Bobby.

“The name is Merrill,” corrected Woodsman firmly, and he limp-wristedly shook hands.

“ . . . Warren? I want to talk to him. . . . some more falafel. . . .”

“And this is Bertha Bankopf,” said Merry, presenting a young woman who looked as though she had carefully planned to be the world’s most stylish schoolteacher: gray flannel suit, white blouse accented by a frilly red bow at the neck, sensible, though feminine, oxfords.

“So happy to meet you,” gushed Bertha. “Of course, I’ve known Mel ever since I came to the university, and I’ve wanted to meet his better half.”

“If we could drag you away for a minute, Bertha and I would like to talk to you.” Merry took Bobby’s arm and led her out of the living room and into the bedroom, Bertha following closely.

“Uh, this is a bit delicate,” explained Merry, “but I’m sure you’ll understand. “Word has been passed down from the top at the university that no one is supposed to approach you about . . . uh, you know . . . about funding. It’s being said that you’re President Newburn’s private property, his new Ophir.”

“And,” said Bertha, “we wouldn’t want the president or anyone in the department to know that we’re talking to you about this. . . .”

“About what?” asked Bobby.

“Bertha and I want to conduct a study, an important piece of work. You see, we believe that literature could be very powerful medicine for a sick society. In a nutshell, we want to give inner city delinquents and addicts intensive courses in literature—everything from Chaucer to Ashbery—to see if it will influence their behavior for the better. We need funds to set the project up, to hire teachers, to assemble and analyze our data.”

“For two hundred and fifty thousand, we could get under way,” Bertha interjected.