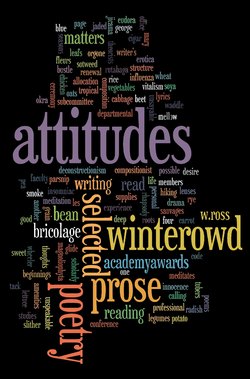

Читать книгу Attitudes - W. Ross Winterowd - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII. Poems

Vegetables

Roots

Parsnip

Ah, parsnip, pallid winter root,

Thou emblem, yes, thou very fruit

Of fallow fields and frozen ways,

I alone will sing thy praise

Before I whack thee quite in two

And add thee to this evening’s stew.

Oh, vegetable melancholic,

When people dine and drink and frolic,

Thou liest in the basement bin,

A beetle bumbling blind therein.

Thou suffer’st yet the vilest taunts:

You’re never served in restaurants.

Carrot

At one time, they were plump and stubby,

Not esthetic, far too chubby;

Often gnarled, but always sapid,

Carrots then were never vapid.

Those sunny roots were full of savor,

Sweet and juicy, earthy flavor.

Carrots now are well designed,

Slim and tapered, quite refined,

But wooden, dry: they have no taste—

For symmetry, gad, what a waste!

Slice it, dice it, scrub it, pare it:

We mourn the passing of the carrot.

Beet

In Moscow:

The blood-red beet, da, khorosho,

We use him for our borshcht, you know.

In other lands, tovarishch beet

Is not considered quite so neat.

In the suburbs:

At cocktail party, barbecue,

I’ve never seen raw beets, have you?

Turnip, carrot, cabbage slice

Dunked in dip is very nice.

Yet palates can by beets be tickled.

Like me, they’re at their best when pickled.

In Cambridge:

From Harvard, graduate cum laude,

Served usually with quohog chowder,

The beet has been an honored guest

With Kissinger and all the rest

At solemn rites when Derek Bok

Asks famous grads to give a talk.

Radish

Listen, you can hear the crunch.

I eat a radish with my lunch.

The radish, wisest of the roots,

Is never cooked and only suits

A relish dish, not a platter,

Or plate or tureen, for that matter.

Imagine radish casserole,

Baked radish in a Pyrex bowl,

Or think of radish under glass,

A humble root gone upper class.

The radish knows it’s best by far

To love ourselves just as we are.

Rutabaga

Forgotten, lost to our cuisine,

Of noble turnip, first cousine,

For rutabaga, royal root,

Strike up the timbrel and the flute.

That she at table proud may reign,

From exile bring her back again.

Ma grandmere served her every week,

With mustard greens and ham and leek.

Rutabagas are, mon dieu!

At least as tasty as les choux.

Jicama

Like the radish, it has crunch,

But if you eat it with your lunch,

You’ll find that it has little flavor,

No zip, no oomph, no snappy savor.

Overweight? The thing to do

Is dine on jicama with tofu.

Because that’s such a tasteless mess,

You’ll lose weight through eating less.

Tubers

Potato

(To be read with a thick German accent.)

At dinner, he is always gut,

Mit Sauerbraten, hardy root,

A glass of Bier, a glass of Wein,

Kartoffel, ja, you’re immer fein.

Vegetable democratisch,

Not a snob or autocratisch,

The rich, the poor, the bourgeoisie

At table gladly welcome thee.

Heil to thee, blithe tuber, spud,

Who comes to us from out the mud.

And now at the Oktoberfest,

Salute the root that we like best.

We raise our mugs in heartfelt toast.

For Kartoffel, shout a “Prost!”

Sweet Potato

The sweet potato, unlike yam,

Is very seldom served with ham.

In fact, it’s barely fit to eat;

It’s mealy and not really sweet.

When we find it’s on the menu,

We try to get a change of venu.

Invited out to dine last night,

We’d have gladly taken flight;

As guests, we had no alibis

And met Pale Tuber in disguise,

Posing as a salad green,

The worst imposture we have seen.

Legumes

Pea

On the vine, it rises high,

Its goal the vastness of the sky.

Secure within its cunning pod,

It soars beyond the earthy sod.

In the ether there with Jack,

It never dreamed of coming back.

The pea—who ever would have thought

It longed to be an astronaut.

In a row by one another,

Sister pea and legume brother,

Secure against the force of G’s,

In their capsule quite at ease,

Had no inkling that their fate

Was actually a dinner plate.

Soya

Since soy bean is a bricoleur,

The handyman without a peer,

When we say “soya” in our house,

We always think of Lévi-Strauss.

Fermented juice of soy’s a sauce

That saves our rice from total loss

Though honestly I must confess

I think tofu’s a tasteless mess.

My farmer friend, I swear, avows

The soybean nourishes his cows.

This legume, whether cooked or raw,

Preoccupies Jacques Derrida.

Bean I

John Kenneth Bean is enigmatic.

With wieners he is democratic,

And yet in Julia’s cassoulet

He turns elitist, slightly fey.

His pronouncements economic

Seem to me a little comic

When with sombrero and guitar

In chili he becomes a star.

With eloquence he makes us humble.

We listen as our stomachs rumble,

Sitting stiff, in mortal terror

Of that most disgraceful error.

Bean II

Professor Twist’s Last Expedition

Ogden Nash’s exposition

Chronicled the expedition

To the land of crocodile,

The upper reaches of the Nile.

I give you now Professor Twist,

A conscientious scientist.

Trustees exclaimed, “He never bungles!”

And sent him off to distant jungles.

Camped on a tropic riverside,

One day he missed his loving bride.

She had, the guide informed him later,

Been eaten by an alligator.

Professor Twist could not but smile.

“You mean,” he said, “a crocodile.”

That was in . . . uh . . . let me see,

The year of nineteen twenty-three.

In thirty-three he set out on

A journey up the Amazon.

After hardship you can’t describe,

He came upon a savage tribe,

Healthy, happy, without disease—

Twist barely reached up to their knees.

Eagerly he told their chief,

“Your followers defy belief.

They get their vigor by what means?”

The chief replied, “We eat-um beans.”

“Beans? Beans? What kind?” Poor Twist was wild.

“Yooman beans!” The chief just smiled.

Grain

Oats

On a frosty winter morn,

I have my choice: oats, wheat, or corn.

In March when all the ways are slush,

I choose to start my day with mush.

Cracked wheat is hearty and nutritious;

Corn meal is soothing and delicious;

But oatmeal laced with heavy cream

And honey globs has my esteem.

You see, in German my name, “Ross,”

Means “stallion.” (You can call me “Hoss.”)

When offered oats at break of day,

We prancing kind just can’t say, “Neigh!”

Wheat

When as a child I walked from school,

Wading through the pool on pool

Of fallen leaves along the way

On lawn and sidewalk where they lay

And heard their rustle and their crunch,

(Three hours ago I’d downed my lunch),

I sniffed the air, a very hound,

Alert to every smell and sound,

The musty odor of the mums,

The chuffing engine’s distant drums,

And saw ripe apples hanging late,

Too high for me to depredate.

A block from home, I pause, I freeze.

The smell of bread is on the breeze.

I clasp my “Dick and Jane” securely,

For I understand most surely

That wheat when ground is more than flour:

It’s endowed with mystic power.

Baking bread in Bombay, Rome,

Or Salt Lake City signals “home.”

Rye

You can serve it slice by slice.

You can pour it over ice.

It goes well with ham or soda,

Vermouth, corned beef, bitters, gouda.

Loaf or bottle, worth a try.

With rye you’ll never go awry.

Rice

“I wouldn’t leave Beijing,” said Mao,

“For all the rice in Sacramento.”

You see, the Chairman clearly knew

A fact that’s shared by very few:

More rice grows in California than

In all of China and Japan.

It was brought here, to be specific,

To labor on the Southern Pacific,

And then, forsaken, had to stay

In Hanford and in San Jose.

It now speaks English fluently

And sends its kids to USC.

Leafs

Sotweed

One leaf should now be doing time,

Life sentence for its horrid crime,

Its disregard for humankind,

Cruelties that numb the mind.

Sotweed dulls the keenest brain

And leaves behind on teeth vile stain,

A rancid odor on the breath—

Tobacco is the herb of death.

Yet as I pen this morbid dirge,

Struggling with the awful urge

To suck in nicotine and tar,

I’m puffing on a huge cigar.

Lettuce

When it’s sliced, I cannot bear it!

Purists always gently tear it

Delicately with their fingers,

Avoiding acrid taste that lingers

From the touch of any metal

On this tender, light green petal.

But lettuce seldom gets its due.

There are really very few

Who eat the leaf ‘neath stuffed tomato

Or salad, tuna or potato.

Left on the plate, wilted, oily,

It’s often nothing but a doily.

Cabbage

A thoroughgoing democrat,

In blue collar and hard hat,

Cabbage has a union card.

On Saturday, he mows his yard,

Watches football Monday night,

Has never missed a major fight;

Subscribes to People, scans the Times

(For weather, scores, and heinous crimes).

Mr. Cabbage is sub dig—

Some would say, “A swine, a pig!”

But this pungent vegetable,

Leader of the plebeian rabble,

Has potential, without doubt:

He’s incipient sauerkraut.

Magnoliophyta

Okra

(at the request of Jim Corder)

Family mallow’s diverse stock

Includes both okra and hollyhock,

Althea shrub, and, indeed,

Rose of Sharon, and velvetweed.

When you served your okra gumbo,

You undoubtedly didn’t know

That your soup was pleonastic—

Rich and spicy and bombastic.

As the dictionary tells you,

Gumbo’s “okra” in Bantu.

Consider, then, this irony:

Okra came across the sea

To pick that field, to cut that cane,

To labor on in woe and pain,

While its cousin sat in state,

King Cotton, mallow’s line enate.

Matters Professional

Deconstructionism

In the heat, beneath the trees,

Ungainly wood between her knees,

A cellist idly weaves her notes.

The melody, I think, connotes

The lazy, endless whirl of mind—

A nebula that’s ill-defined—

Toward a center, resting place,

Stability in boundless space.

The Jaded Compositionist Meditates on His Calling During an Attack of Influenza

Thank God, I say, for student essays!

They let us while away our days

In what we hope is harmless work,

Hunting for the errors that lurk

Within the Twinky prose.

Those acne essays—we’ve tried, heaven knows,

To improve their complexion

By noting each and every possible correction,

And feeding their authors, without apology,

Nutritious fare from the Norton anthology.

We may do some good; we hope so.

In any case, this much we do know:

The essays probably won’t be terrific, Yet they’ll serve as a soporific

To deaden the pain of arthritis or flu.

Ah yes, our themes will see us through

The dismal dregs of sniffling Sundays,

The aching, hacking nights of Mondays,

Weekend, weekday—noses or knees, heads or backs,

Wherever the malady, themes help us relax.

Those narcotic anodynes, those horrendous stacks—We need them. We’re nothing but pitiful hacks,

Self-righteously flaunting devotion to duty,

To error-free prose and to truth and to beauty,

When we know for a fact (and this is sublime):

Our mission is really just to kill time.

Slither, Bustle, Waddle, and Glide, Members of the Departmental Subcommittee on Allocation of Office Supplies and Faculty Amenities

He Slithers in and hisses greeting.

“This will be a busy meeting.”

She Bustles primly to her chair.

“This will be a great affair.”

She Waddles dourly to her seat.

“I’m glad,” she grunts, “that we can meet.”

He Glides along; he doesn’t walk.

“We’re alone, so we can talk.”

Glide looks thoughtful, wise, profound.

Waddle doesn’t make a sound.

Bustle’s manner is officious.

Slither’s start is . . . well . . . auspicious.

“This is,” in hiss, “a vital matter.”

“Indeed, indeed!” is Bustle’s natter.

“I agree!”—that’s Waddle’s rumble.

Glide advises, “We can’t bumble.”

Slither strokes his flowing hair.

Bustle wriggles in her chair.

Waddle wakes, her head upreared.

Glide is playing with his beard.

“We’ll talk some more,” he firmly states.

Waddle’s nod asseverates.

Triumphant Bustle says, “Ahem!”

And Slither names her chair pro tem.

Slither says, “A job well done.”

Bustle adds, “I have to run.”

Waddle mutters her adieux,

And Glide: “I’ve many things to do.”

One now Slithers out the door,

And then out Bustles yet one more.

The third one Waddles down the hall.

The last one Glides, and that is all.

Meditation at a Scholarly Conference

We celebrate our solemn rite.

We genuflect; we mumble prayer.

The priestess, personable and bright,

Legitimates the whole affair.

A sermon launched, we sip our wine,

A blessed, welcome sacrament.

Our ardor, though, will soon decline

For the blessed testament.

We endure the sacred mass,

Holding to the ancient creed,

Knowing in our hearts at last

Learned talk is what we need.

We celebrate the frequent rite,

Renewing our belief.

The “Amen” said, our faith is bright,

And we adjourn with great relief.

Erotica

Hiking Wheeler

With candles, groping down through Lehman Cave,

We chased the shadows of reality

And saw the cavern as John Lehman had.

The flicker led him back and back toward

A treasure. In the greatest Saal he dreamed

A courtly dance, the fiddles tuning up,

Their echoes crinoline and riding boots.

Emerging in the blaring sun, we blinked

And wiped our eyes; newborn, we tottered stunned,

Our bleary gaze toward the misted peak.

An easy climb through pine and aspen glades.

I watched the muscles flexing in her legs,

Her working buttocks tight within her shorts,

And heard her breathing deeply in thin air,

The quartz shards clinking with her every step.

When we reached the bristlecones, we paused

To ponder those tenacious trees, so gnarled,

But not eternal, no, yet nearly so

As anything on earth. The cones were bright

With golden honey, fecund, pregnant, ripe.

We ate our M&M’s in pinescent air

And sipped the lukewarm water from canteens.

Above the timber, scrambling through the scree,

We reached the cirque, the glistening our goal,

Then crunched through ice upon the glacier’s face,

And on the farther side, sat peacefully.

We’ll take the hike again, again, perhaps,

But someday we’ll just stay there, glacier-bound,

Side by side, thinking of the bristlecones,

The M&M’s, the water, and the scree.

Eudora (on having read One Writer’s Beginnings, by another Eudora)

In the sixth grade, Eudora Britton

Had budding bubs.

She wore rouge and lipstick.

She looked, I think, like Ava Gardner,

Hideous,

So repulsive that we boys stampeded,

Terrified when the teacher led her

Toward us across the gym for pairing,

To practice waltz and foxtrot.

I remember her full-lipped crimson smile

Above the sweater and the sagging bobbysox,

That Wonderland smile, fixed, immobile.

As she neared us, towed by Miss Hayes,

We giggled, milling in the corner.

The Deep Structure of Desire

If I say to you, “The log is ashes,”

You aren’t puzzled in the least.

You’ve known logs—known your father to chop them

For the black, wood-burning stove your mother used to cook the chili sauce in fall

(Ah, its redolence through the house!)

and to give the upstairs bedrooms

just a bit of heat,

just enough to keep you and Sister Beulah,

huddling together under the heavy quilts

your mother made, huddling there, the two of you together, in the bitter Mormon cold of January—

just enough heat to keep the two of you

not cold, not warm, but in a middle state

that made the huddling sweet.

And yet you should be puzzled.

For, my love and friend,

if the log is ashes it is no longer log.

Something which was the log is now ashes.

Here is another puzzle for you:

You, my wife, were born in Fairview.

But, love, when you were born,

you were not my wife—

though no doubt destined by our Mormon God

through eternity, you for me, me for you,

one couple indivisible, with no liberty and much justice for both.

Our language fools us.

Our moods are trout that sulk beneath

a log (which is not ashes) and then jump flashing

at a mayfly or a hackled hook.

Finish cooking the dinner.

But if it is not cooked,

how can it be a dinner?

The truth is hard to get at.

Here is a true-untrue story.

Our oldest son got lost in the mountains.

(Just Southern California mountains.

Not Alaska. Not that alarming. He told us

that the smog was bad.)

And so I’ll begin my story with

“Our youngest son got lost in the mountains.”

And you’ll say, “That’s wrong.”

So I’ll rephrase: “Our youngest son

didn’t get lost in the mountains.”

And you’ll say, “But that’s beside the point.”

And I’ll say, “Someone who is not our youngest

son got lost in the mountains.”

“Ah,” you’ll say, “now we can get on with the tale.”

So truth is not the exact opposite of untruth.

The truth is hard to find.

Or is it?

My sentences hide the truth.

That is my whole problem.

The truth must lurk,

like a trout beneath a log,

somewhere below what I say.

The log was once a tree.

The log is now ashes.

The tree, of course, had branches.

And, in this essay, we are led to a terrible

but inevitable pun: branching tree.

I can do an elegant diagram of The log is ashes.

In its geometrical neatness, it would satisfy you, my love,

as much as whatever music you wanted to name.

But no diagram will show my desire.

All I can say is that my desire has about it

its enigmas, its ambiguities.

It has a deep structure I could never catch.

Matters Personal

Lenses

Galileo explored the night,

His lens extending human sight

Back and back toward the place

Where time began its stately pace.

Old Dutchman with his home-made lens,

Leeuwenhoek found teeming fens

In a drop of H20,

Beasties darting to and fro.

Trained upon a blade of grass,

Great Grandma’s magnifying glass

Gathered sunlight to a spot,

Blinding pinhead, shaft white-hot.

Through our lens, our son’s first son,

Our miracle, our glowing one,

Past and future gain their focus,

A bright, melodic, fragrant locus.

With George and Mary

Somehow the place so fits our friends:

the quiet flow of the river,

the elegant silver trees,

a honker landing just now

and drifting serenely with the current;

the quiet flow of the music,

the elegant, airy room,

the easy talk resumed just now

and drifting serenely on.

Our friends deserve this lovely place,

A house of understated grace,

For all their Acts, the perfect Scene,

A beauty joyful and serene.

Code Blue

The soothing voice, verbal Muzak,

Announces “Code blue. One east.”

Some crisis—stroke or heart attack.

“Code blue,” the Valium voice repeats.

The young blonde doctor, so patrician,

Crisply practices her trade

And seems the responsible physician,

Until she giggles at a joke I’ve made.

“Noninvasive Procedures” says the sign,

And so my territory is safe against attack.

A pacifist, I sigh, obey, resign

Myself to lying quietly upon my back,

Looking up at the doctor’s serious face,

Hoping that her giggle will not come,

Apprehensive in this alien place,

Wondering if she chews bubble gum.

Les Fleurs Sauvages

The savage flowers of Crete,

Geraniums, redder than Achaean blood;

Roses, blood red,

Clustered in the brilliant sun,

Ready for attack.

Oleander everywhere, scarlet phalanxes,

Infiltrating hillsides,

Guarding highways.

More sun than I have ever known,

And brighter, clearer.

Here, just off the coast,

Two small islands—

The next stop Africa.

They ski at Omolo,

And in winter,

The eternal shepherds

Move their flocks

To the coastal plain.

Mellow Drama

“Dear Aunt and Uncle,” wrote Denise,

Our daring, nonconformist niece,

“I had my ears pierced. Mom and Dad

“Didn’t know, and were they mad!

“I bought myself a pair of earings,

“Lipstick, ruge, and other things.

“I had a big suprise for mama.

“I’m staring in a mellow drama.

“Send some fashion pictures, please.

“From your loving niece Denise.”

Dear Niece:

May you be the morning star,

Glowing in the light of dawn.

May you be the evening star,

Shining when the light is gone.

May you ever be the star

Of mellow drama all life long.

Your loving aunt and uncle.

“But a good cigar is a smoke”

This hoary joke

Is worth a smile, perhaps a chuckle,

Medicine for those who knuckle

Under to their pumping glands

(The covert leers, the trembling hands)—

Not females, no: testosterone,

The liquor that unmixed, alone,

Taken straight, not on the rocks,

Deadens brains and rouses libidinous desires.

More avidly I puff my stogy;

I’m lecherous, a raw old fogy.

Ah, whatever might have been,

I’m now a senior citizen,

With glabrous pate and sagging skin.

Too late, alas, to live in sin.

Thank Jove, I say, for senile vice;

It’s not exciting, but it’s nice.

Cigars and such, as Freud well knew,

Keep one going, see one through.

And when at last my hormones cease,

I’ll puff away my life in peace.

How to Read a Page

Like Henry Ford, who mined the Mesabi,

Ore for River Rouge.

The great plant smoked and fumed and clanked.

Ore in one end,

And out the other, Model A’s.

Like Evel Knievel, gunning his bike,

Metallic thunder down the track,

Up the ramp, over the abyss.

Kerthump! the hind wheel hits the dirt.

Through a cloud of dust and exhaust,

The rider takes his bow.

Like a hawk circling high,

But tighter, tighter, above the rabbit, crouched and trembling;

Then the plunge, the miss;

Wings pulsing, the struggle upward;

The lazy glide on the thermals;

Then circling high in tighter spirals.

The plunge.

Like Grandpa strolling in the park,

Pausing now and then to feel the breeze,

Waiting for the child totteringly to catch up;

Then, hand in hand, onward,

Both silent in the swish of fallen leaves.

Hot chocolate at a sunny table

In the stand beside the lake.

Like Uncle Jim, whose story was the telling,

On the porch at gloaming.