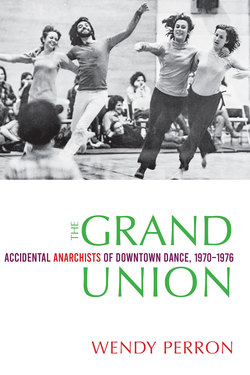

Читать книгу The Grand Union - Wendy Perron - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

ONLY IN SOHO

The scattered community of artists in Lower Manhattan continued to experiment into the seventies across disciplines, fervor undimmed. But finding affordable living and working space was an uphill battle. A solution was masterminded by Lithuanian immigrant and madcap visionary George Maciunas. Informed by ideas from Bauhaus and European agriculture collectives, he jumpstarted an artists’ colony in SoHo (the area from Houston Street to Canal Street, and from Sixth Avenue to Crosby or Lafayette Street, aka the cast-iron district) by setting up 80 Wooster Street as a cooperative “Fluxhouse.”

At the same time, the interdisciplinary hub of 112 Greene Street was fertile soil for SoHo’s budding art colony. Pioneering visual artists and performance artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, Vito Acconci, Richard Serra, Laurie Anderson, Alan Saret, and Richard Nonas added to the rich cross-disciplinary ferment, as did composers Philip Glass, Richard Landry, and Ornette Coleman. Venues in SoHo that presented dance and performance included The Kitchen, founded by video artists, and galleries run by Paula Cooper and Holly Solomon. It wasn’t much of a stretch for Laurie Anderson to call SoHo of that period the center of the art world.1

∎

In 1967 the artists who had been involved with Judson started hearing that George Maciunas was buying loft buildings in SoHo and selling them cheap to artists. Small manufacturers of clothing, corrugated boxes, candy, or dolls were fleeing New York, leaving behind a landscape of empty warehouses. Maciunas, later known as the “father of SoHo,” had a vision of cooperative loft living for artists. In exchange for taking on the risks of illegal occupancy, artists paid a low price for gobs of space. Maciunas was charging only two dollars a square foot, and word spread like wildfire.2 According to performer and movement therapist Joseph Schlichter, Trisha Brown’s husband at the time, “Everyone in Judson Theater was rumbling about it. There were 150 or 160 people who were interested. We had to roll dice to determine who got in.”3

Maciunas, who came to these shores in 1948, had studied architecture at Cooper Union and Carnegie Institute of Technology. He had also studied with Richard Maxfield, a student in John Cage’s famous course in experimental composition at the New School, instilling in him an interest in artists who were mixing genres. As the leading member of Fluxus, he gave the group its name and organized events in both Europe and New York.

Maciunas fought for what he believed—in eccentric ways. Charles Ross recalled him chasing away a city building inspector with a samurai sword. Maciunas once bought two huge batter mixers from a baker and installed one as his bathtub.4 He aligned himself with the Soviet ideal of workers sharing in ownership. According to Sally Banes, he even called his cooperatives kolkhoz, the Russian word for collective farm.5 He not only organized housing for artists but also got them work. He hired musicians as plumbers, including Philip Glass, Rhys Chatham, and Yoshi Wada, who used giant plumbing pipes to make new sounds.6

The first artist to go in with Maciunas, in 1967, was filmmaker Jonas Mekas, a fellow Lithuanian immigrant. Mekas and Maciunas transformed the ground floor of 80 Wooster Street into Fluxhouse Cooperative II. (Fluxhouse I, on Greene Street, was eventually repurposed.)7 It became the new home for the roving Filmmaker’s Cinematheque, which showed films by avant-garde filmmakers like Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Andy Warhol, as well as Mekas.8 Others who performed there included poet Allen Ginsberg and video pioneer Nam June Paik.9 Because Yoko Ono was an active Fluxus artist, sometimes she would drop by with John Lennon.10 It was there that Philip Glass presented the first concert of his own work in 1968.11 But because of lack of proper licensing, the Fluxhouse only lasted until July 1968. Budding theater director Richard Foreman, who had helped to build the theater, then produced four of his early plays there.12

Trisha Brown and Joseph Schlichter moved into the top floor of 80 Wooster with their two-year-old son, Adam. In the beginning, the building’s only bathroom was in the basement. Running water did not reach the seventh floor, so Trisha would bring a bucket to a lower floor and fill it from a spigot every day.13 Schlichter grew marijuana and tomatoes on the roof and used the water tower as a swimming pool for children—to the dismay of other parents.14

Sculptor Charles Ross, the mastermind behind the collaborative Concert #13 at Judson, moved into the fourth floor.15 Conceptual artist Robert Watts, who was involved in happenings along with Allan Kaprow, moved into the fifth floor.

Brown found the raw space to be fertile ground for her choreographic—and architectural—imagination. In a way, she was collaborating with the space around her rather than with other artists. In workshops, she gave students the instruction to “read the wall.” The idea was simply to let one’s body respond to the markings on the well-worn wall. In 1967 she drove foot holes into her wall “in order to reach the ceiling but also to move on a vertical plane.”16 This was undoubtedly in preparation for her 1968 equipment piece Planes. She started off her 1970 concert “Dances In and Around 80 Wooster Street,” with her iconic daredevil work Man Walking Down the Side of a Building. A tiny audience clustered below in the courtyard, looking up in awe. The film of this event17 shows a man at the top of 80 Wooster, facing downward, body horizontal, walking so slowly and deliberately that he could just as well be taking the first steps on the moon. (This was only a year after the Apollo moon landing was seen on television.) SoHo artists Richard Nonas, Jared Bark, and David Bradshaw stood on the roof and let the cord out safely.18 Then the audience went inside the building to see Floor of the Forest, in which Brown and Carmen Beuchat crawled on an eye-level grid of horizontal ropes that were strung with garments. The two slithered into and out of the shirts, pants, and dresses. With this work, Brown brought the domestic mess of family life to the pristine grid of minimalism. At the same time, the piece referred to the uneven terrain of the forest, which Brown had called her “first art lesson.”19 Audience members had to create their own uneven terrain, squatting down or rising up to get a glimpse of the performers.

Last, the audience went outside onto Wooster Street to see Brown’s Leaning Duets I. This was a partnering task dance related to what she had been exposed to on Anna Halprin’s deck as well as to Forti’s Slant Board (1961) and her own Planes. Five pairs of people had to keep their feet in contact with their partner’s feet while leaning away from each other and trying to take steps without falling. The two would talk to each other (“Give me more of your weight” or “I need to twist to my left”) to keep in balance and go forward. This kind of discuss-what-you-are-doing banter became rife in Grand Union.

Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), by Trisha Brown. Joseph Schlichter, 80 Wooster Street. Photo: Carol Goodden.

When Brown moved into SoHo, huge trucks were moving through the streets to deliver rags or other cargo to manufacturers. She picked up the lingo of the driver teams and brought those commands into Grand Union. In the last performance at LoGiudice Gallery,20 during an ultra-slow, ultra-gentle duet between Gordon and Paxton, she carried on with a gruff, street voice: “Easy now, easy now, easy now. C’mon now. Move it along, move it along. Over we go, now. C’mon, easy does it. Let’s go, move it, keep it going. Keep it movin’, keep it movin’. Up and over, watch out now. Move it along. [Th]at’s it, easy does it.”

Brown wasn’t dreaming of dancing in a theater. Learning her Bauhaus lessons well, she made her art in the place where she lived. “All of the pieces I performed at 80 Wooster had rambled in my head for a long time. My rule was, if an idea doesn’t disappear by natural cause, then it has to be done. I wanted to work with the wall but not by building one. I looked at walls in warehouses and as I moved around the streets … I chose this exterior wall and then thought—why not use mountain climbing equipment?”21

Brown also made short works at other sites in SoHo. Her Roof Piece premiered with audiences viewing from 53 Wooster Street in 1971; Woman Walking Down a Ladder (1973) took place on the rooftop of 130 Greene Street; Group Primary Accumulation premiered at Sonnabend Gallery the same year (later to be performed in Central Park and other outdoor areas); and Spiral (1974) was inspired by the columns at 383 West Broadway (later Ivan Karp’s OK Harris Gallery), where she also premiered Pamplona Stones.22 When she reprised Roof Piece in 1973, retitling it Roof and Fire Piece, the number of rooftops stretched to fifteen.23 The photograph of this piece, taken in 1973 by Babette Mangolte, later came to represent the revolutionary SoHo arts scene to Europe.24

∎

Roof Piece (1971), by Trisha Brown. Foreground: Sylvia Palacios Whitman; at upper left, Douglas Dunn. Photo: Babette Mangolte, 1973.

Although Maciunas was creating a cooperative artist colony with what he considered a “selfless spirit of collectivism,”25 he was an autocrat. With an architect’s training, he was very sure of what he wanted. As Richard Foreman recalled, “He saw things in his own way and if you didn’t accept the way he saw things happening, he would get very mad.”26 Foreman described working with Maciunas as “a kind of a perverse spiritual test.”27

Maciunas, however, cared about the artists he knew and alerted them if a good deal came up. When he discovered 541 Broadway, with its good proportions (wider than the usual twenty-five feet), no interior columns, and floors made of wood—not just wood over concrete—he knew it would be perfect for dancing. He contacted Trisha Brown, who relocated there in 1974 or 1975, soon to be followed by David Gordon and Valda Setterfield.28 Douglas Dunn moved there, from a block away, in 1982.29 Lucinda Childs of the Judson days also lived in the building, and on the Mercer Street side lived—and still live—hybrid artists Joan Jonas and Jackie Winsor. Simone Forti, along with dance artist Frances Alenikoff, musician Yoshi Wada, and artist Emily Harvey, lived in the next building at 537 Broadway.

Maciunas felt that his artists’ colony, which grew to sixteen buildings over ten years, was in line with the ideals of Bauhaus and Black Mountain.30 In the Cagean and Fluxus spirit of making art out of everyday life, he was creating spaces where artists lived, made work, and gathered. Trisha Brown, with her uncanny ability to nestle the human body into, or use the body to extend, existing architecture, was in line with Maciunas’s vision. Brown helped shape the values of SoHo and vice versa. During this period, she was working with Grand Union as well as making her equipment pieces and accumulation pieces.

Like Brown, both Marilyn Wood and Mary Overlie devised ways to embed the moving body into the SoHo landscape. A former Cunningham dancer, Wood devoted herself to site-specific dance, performing internationally with her Celebration Group as well as on the fire escapes on Prince Street. In 1976 and 1977 Overlie, who had performed a speaking role in Rainer’s piece at Oberlin in 1972 and had been a guest of Grand Union at 112 Greene Street in 1972, performed with her dancers in the windows of Holly Solomon Gallery, creating a stir of enchantment on West Broadway.31

∎

Another hotspot in SoHo made possible by low cost was 112 Greene Street. A cluster of artists, including married couple Jeffrey Lew, a self-styled anarchist, and Rachel Wood, a dancer, inhabited the building. They had bought the building—Wood had family money—directly from a rag factory in 1970.32 The pioneering site artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who briefly lived in the basement, was constantly altering the space with his outrageously deconstructionist actions. In an episode of “guerrilla gardening,” he piled soil into a small hill in the basement and planted a cherry tree in it. In order to give the tree space to grow, he cut a big hole in the ground floor of the building, which became his signature mode—literally deconstructing buildings. Though he died in 1978, he is known as one of the great instigators of large-scale, space-altering work, addressing the deterioration of New York City buildings with his manic imagination. Matta-Clark, whose godfather was Marcel Duchamp,33 was a forbear of later huge projects by the likes of site artists James Turrell, Michael Heizer, and Christo.34

Glass Imagination II (1977), by Mary Overlie. Photo: Theo Robinson.

The glory of the lone artist, however, was losing its luster. In his book Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the ’60s, cultural critic Richard Goldstein wrote this in reaction to Norman Mailer’s novel Armies of the Night: “[I]t seemed like a violation of the countercultural ethos that I’d come to share. We kids saw politics as a collective activity, something we did together. Radicals in Mailer’s generation had struggled to maintain their individuality, but we fought to maintain community.”35

During this period, 112 Greene became a hangout for all kinds of artists and dancers, including Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, Nancy Lewis, and Steve Paxton. Rachel Wood was a member of Dilley’s group, the Natural History of the American Dancer. This all-woman group also included Carmen Beuchat (who was also dancing with Brown), Cynthia Hedstrom, Mary Overlie, Suzanne Harris, and Judy Padow.

GU at 112 Greene Street, 1972. From left: Paxton, Lewis, Overlie (as guest), Rainer (face hidden), Scott in chair. Photo: Babette Mangolte.

The works that took up space at 112 Greene broke all existing conventions of art-making etiquette. Louise Sørensen, in the introduction to 112 Greene Street: The Early Years, wrote that “112 Greene Street was synonymous with a remarkably concentrated period of the New York art world where creativity and idealism went hand in hand—a product, no doubt, of the 1960s counter-culture.”36 It was a non-gallery gallery. As conceptual artist Bill Beckley recalled, it “was a raunchy kind of place where you sometimes couldn’t tell the mess from the art or vice versa.”37

SoHo was a counterculture in both art and leisure. Its artists were decidedly uncommercial, not looking to make money from their art. Beckley felt they were “redefining” art. “It was the cusp of modernism and postmodernism.”38 Some called them “post-minimalist.”39 The social life mingled with the art life. According to Rachel Wood, “[W]e had incredible parties: rock ’n’ roll music, dope and alcohol, and dancing like mad for hours.”40

Padow, who also lived at 112 Greene, described how the group named the Natural History of the American Dancer emerged from those parties: “It’s a party but everyone’s dancing and improvising. It got formed almost like an outgrowth of the lifestyle at 112 Greene Street. There was not a fine line between having dinner and performing eating dinner. Someone sitting on a sofa would rise up and suddenly you’d notice that someone else has risen. The cues … the picking up of someone else’s gestures would happen at a spontaneous level.”41

Paxton, however, doesn’t feel that 112 Greene held a corner on this kind of social life. Asked, via email, if he felt 112 provided the soil for endeavors like Grand Union, he replied: “The times were that soil, I believe. The transition of SoHo into artists’ spaces rendered it especially fertile; a failing industrial area was transformed into a colony of activist artists, musicians, poets, dancers [having] huge parties, pranks, hijinks, performances and a confluence of a new generation of artists.”42

Douglas Dunn often went to the dancing parties at the Byrd Hoffman School for Birds on Spring Street, the studio of experimental theater director Robert Wilson. Daily improvisation sessions there also bled into social parties. “These places were so cheap and it was so much fun and so interactive. Grand Union was sort of an extension of this kind of familiarity and intimacy of artists at that time.”43 The sexual revolution was still young, and the calamity of AIDS hadn’t hit yet. “There was plenty of erotic energy in the mix and sometimes it ended up being physical connections and sometimes it didn’t,” Dunn said. “It was one of the driving forces, not just in Grand Union but in SoHo in that era. Sometimes these relationships fed the work and sometimes they distracted from it.”44 A graphic that reflects that randiness, with a certain elusive humor, is the flyer that Paxton designed for the February 1971 performances at Bob Fiore’s loft on East 13th Street.

∎

The 112 Greene Street denizens, like many young artists, tended to be skeptical of capitalism and against the war in Vietnam. According to artist Mary Heilmann, “Most of us came to 112 as bohemian outsiders and almost Marxists—against capitalist culture.”45 According to Rachel Wood, Jeffrey Lew was so opposed to art making as moneymaking that one of his criteria for accepting a work of art at 112 Greene was that it not be intended for sale.46 It was more honorable to make work that was embedded in the life they were living. In 1972 Matta-Clark made a piece called Walls Paper, for which he photographed walls of decaying buildings, made giant prints of them, and mounted them up on the walls of 112 as a new kind of wallpaper.47 Also in 1972, he made a performance piece in a dumpster on Greene Street. Beckley’s memory: “[Y]ou saw the umbrellas peeking up from the dumpster, moving around. That was pretty good.”48 As with Trisha Brown, this was part of the aesthetic of bringing art outside the gallery or theater and into the streets.

Flyer designed by Steve Paxton based on a Japanese wood print, 1971. Photo: Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Another urban project of Matta-Clark’s brought graffiti writers down from the Bronx. He photographed sides of subway cars, mounted them on long panels, and set them up as an exhibit on a Mercer Street sidewalk. According to Terry O’Reilly, who assisted him, “Originally he set up his camera on subway platforms and photographed the trains when they came to a stop. This did not work well, so he went out to the train yards and broke into the yards just like the kids would do and photographed their work.”49 Matta-Clark’s application to exhibit these images at the Washington Square Art Fair was rejected, so he parked his delivery truck and invited his graffiti friends to decorate the truck. At the same time, he displayed some of his train-sized photographs of their work, which he called photoglyphs, right there on the sidewalk and called it the Alternatives to Washington Square Art Fair; he exhibited more photoglyphs at 112 Greene. This celebration of the “ordinary” predates the art world’s love affair with graffiti.50 (But I note that Twyla Tharp had already gotten the idea to have graffiti writers onstage as part of the set design for Deuce Coupe, which premiered with the Joffrey Ballet in 1973.)

Matta-Clark’s anarchistic streak was reinforced by others at 112 Greene Street. As the casually organized “Anarchitecture” group—which included Matta-Clark, Harris, Nonas, Carol Goodden, Jene Highstein, Tina Girouard, and Laurie Anderson—they would get together and discuss architecture, space, language, and the possibility of subverting existing norms.51 They held an exhibit of their work in March 1974 at 112 Greene Street. Each artist contributed anonymous photographs that she or he felt represented her or his “idea of anarchitecture, such as liminal or overlooked spaces, and they made the works look anonymous.”52 It was the last show at 112 Greene.

The sense of possibility in SoHo was heady. Highstein (who found mover’s work for his cousin Philip Glass in SoHo) called 112 Greene “a free-for-all…. It really was an open forum. It didn’t have any structure. It was just a room, a big room where anything could happen.”53 Like Trisha Brown at 80 Wooster Street, the artists were finding ways to fit their actions into the existing architecture. Sculptor Richard Nonas, who helped Brown outfit her performers in harnesses for her gravity-defying equipment dances, said, “There was no separation between the works and the space.”54 And, possibly because there was no profit on the horizon, things were fluid. Multidisciplinary artist Tina Girouard (video, installation, fabric, paintings) recalled that the exhibitions would change continually, becoming more like performance.55 Suzanne Harris, who had performed with Brown, produced a double installation of Flying Machine and The Wheels in 1973. For the first, she invited viewers to strap themselves to ropes attached to a specially made ceiling. Next to it was a contraption made of four large wheels that audience members could set in motion.56 “The base of it stayed stable but the different parts rotated,” Beckley recalled. “She went from one rotating thing to another. It was like a bridge from the sculptural aspects of 112 to the dance.”57 Others who presented performances or exhibits at 112 Greene were Vito Acconci, Alice Aycock, Jared Bark, Joseph Beuys, Keith Sonnier, and William Wegman. The Grand Union performed there in February 1972 with Mary Overlie as a guest.

∎

Since they didn’t want to make a living from their art, this cluster of close-knit friends, having given many dinner and dance parties, figured out how to create a communal business: they opened the restaurant FOOD. In 1971 Carol Goodden, who was living with Matta-Clark and dancing with Trisha Brown, bought a small Puerto Rican food shop on the corner of Prince and Wooster Streets. With the help of other SoHo friends, they transformed it into a center run by and for artists. Philip Glass installed the radiators,58 and visual artist Jared Bark put up a new ceiling.59 Goodden was determined to pay artists well for their work and accommodate them with flexible hours.60 FOOD was the only restaurant in the neighborhood with healthy fare, a welcome warm spot on the otherwise empty streets. It specialized in fresh fish, soups, and salads, and the menu changed daily. Members of the theater group Mabou Mines, musicians from Philip Glass’s ensemble, and dancers of the Natural History of the American Dancer cooked, served, and stocked supplies. When it was her turn to cook, Barbara Dilley made food you ate with your hands: “Shells from mussels in broth become scoops for rice pilaf. There were artichokes to dip in melted lemon butter.”61 Nancy Lewis remembers making salads while her future husband, musician Richard Peck, washed dishes.62 Artist Robert Kushner was dessert chef. Everything about FOOD was cooperative. They took turns cooking, relying on family recipes and artistic flair for presentation. Rauschenberg, Don Judd, and Keith Sonnier all did stints as guest chefs.63

In one of his first acts of deconstruction, Matta-Clark tore down the walls separating the kitchen and dining area, putting the cooking in full view of patrons as though it were a performance. In fact, Goodden and Matta-Clark thought of FOOD as a long-term art piece.64 One example of Matta-Clark’s food art is described by Claire Barliant in Paris Review: “Gordon did a meal called Matta-Bones, where everything he served was on the bone and at the end he drilled holes through the bones to make necklaces.”65

Woman Walking Down a Ladder (1973), by Trisha Brown, 130 Greene Street. Photo: Babette Mangolte.

FOOD thrived as an artist-run restaurant from 1971 to 1974, when it changed hands. (The heyday of 112 Greene Street also ended in 1974; in the eighties it morphed into White Columns in the West Village.) Throwing themselves into the work at the restaurant exemplifies Marcuse’s concept of “erotic labor.” Richard Goldstein interprets that to mean the kind of work that “enlists your deepest passions…. Lots of people found the pleasures of erotic labor in political organizing. This was about work as an act of love. Marcuse made me see that when work is love it can be liberating.”66

∎

It’s often been said that SoHo in the seventies was ideal for artists. But the questions come up: For whom was it ideal, and who got left out? It’s no secret that the population in SoHo was largely white, young Americans.

It should be noted, however, that there was a parallel pocket of fervent dance activity for a more diverse group of dance artists about three miles north. Alvin Ailey had helped launch Clark Center for the Performing Arts as a midtown dance space. Affiliated with the Westside YWCA, Clark Center was a crucial hub of dance that was much more racially inclusive than SoHo. Some of the dance artists nurtured in this studio at Eighth Avenue at 50th Street were Rod Rodgers, Eleo Pomare, Donald McKayle, Mariko Sanjo, Brenda Dixon (later Brenda Dixon Gottschild), Dianne McIntyre, William Dunas, Elizabeth Keen, Chuck Davis (founder of DanceAfrica), and Tina Ramirez (founder of Ballet Hispanico).67 During the 1969–1970 season, I often rehearsed there with Rudy Perez, who had performed at Judson from the start and later became a pillar of postmodern dance in Los Angeles. Performances at Clark Center were more fully produced and more accepted by the modern dance establishment than the anything-goes escapades in downtown studios. The choreographers at Clark Center were clearly preparing for the stage rather than for a loft space or art gallery. Dancer/scholar Danielle Goldman points out that Ailey and his repertoire used “metaphors of uplift” that were aligned with historic modern dance.68

Banes has noted: “Postmodern dance was seen by many African American dancers as dry formalism, while African American dance was considered by some white postmodernists as too emotional and overexplicit politically.”69 But a handful of dancers—Gus Solomons jr, Laura Dean, Meredith Monk—shuttled between Clark Center and SoHo. They were accepted socially and aesthetically in both milieus. Solomons explains why most black dancers were not drawn to the aesthetic of Grand Union: “Black audiences and artists typically were interested in messages, be they of rebellion, oppression, or emotion. In general, they didn’t see the point in making work that was only about itself and not the human condition as they experienced it.”70 I might quibble with his depiction of downtown dance as not representing the human condition, but his point is well taken.

It wasn’t until 1982, when Ishmael Houston-Jones curated a slate of African American dance artists for a series called Parallels at Danspace Project, that many of us recognized that postmodern dance was attracting more black dancers than it had before. Danspace, a center of downtown (heretofore mostly white) dance, had been costarted by Dilley in 1974. When curating Parallels, Houston-Jones included not only Solomons and others who had crossed the black/white divide long before, like Harry Whittaker Sheppard and Blondell Cummings, but also younger dance artists like Ralph Lemon, Bebe Miller, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. This series created space for black dancers to feel welcomed in downtown dance houses. They were part of a vibrant postmodern dance as a new art form.

As author Richard Kostelanetz pointed out, SoHo in the seventies was particularly hospitable to new forms of art.71 While Clark Center nobly upheld the tradition of modern dance, experiments in holography, video art, and book art (and as we have seen, food art) were sprouting up in SoHo or nearby. The Kitchen Center opened in the Broadway Central Hotel in 1971, specifically to nurture the new art form of video.72 In 1973, when it moved to Broome and Wooster Streets, it welcomed music, soon to be followed by performance art and dance. (When the Grand Union performed there in 1974, Kathy Duncan’s review called the troupe a “utopian democracy.”)73 The Kitchen fostered the careers of dancers and other artists who brazenly crossed lines of genre and etiquette, for example Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Karen Finley, Eric Bogosian, Molissa Fenley, Christian Marclay, Charles Atlas, and Robert Ashley. (My dance company too was presented there.) With a professional staff to generate publicity and raise funds, it was a more polished operation than either 80 Wooster or 112 Greene. The Kitchen could commission new works and could even send an interdisciplinary band of experimental artists to tour Europe.

∎

John Cage’s ideas pervaded SoHo like a mist. Visual artists like Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Donald Judd were redefining American art, forming all kinds of hybrids and crossovers. Judd presented Philip Glass and his ensemble at his building on Spring Street, the first of a string of gigs for the Glass Ensemble in galleries and museums.74 Just outside the bounds of SoHo, places like Printed Matter (for artists’ books), La MaMa (for experimental theater), The Living Theatre, and The Clocktower (similar to The Kitchen but more site-specific) added to the mix.

The desire to bust out of cultural or genre straitjackets continued into the seventies, and SoHo provided spaces for that to happen. As sculptor Suzanne Harris said, “We didn’t need the rest of the world. Rather than attacking a system that was already there, we chose to build a world of our own.”75

That world was supported by Avalanche, a maverick art publication that considered itself a sibling to 112 Greene and FOOD, where it was available to peruse. Avalanche advocated new genres like earth art, body art, collaborations, video art, and installation. The cofounders, Liza Béar and Willoughby Sharp, were part of the art scene and presented text and images from the artists’ point of view. Grand Union members were often interviewed, and three of Avalanche’s thirteen issues, which spanned the same six years as Grand Union, devoted cover stories to Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Dilley, and Steve Paxton. When Grand Union performed in Buffalo in 1973, Avalanche coeditor Liza Béar, staff photographer Gwenn Thomas, and production person Linda Lawton drove up to Buffalo to shoot and audiotape the performance. They produced a new response form: photographs with dialog bubbles taken directly from the dancer’s improvised conversations.

Excerpt of Avalanche’s comic strip in response to GU’s performance at Buffalo State College, 1973. Design by Willoughby Sharp, photos by Gwenn Thomas, editing by Liza Béar and Linda Lawton, lettering by Jean Izzo. Appeared in Avalanche 8 (Summer/Fall 1973). Courtesy of Liza Béar and the Estate of Willoughby Sharp.

INTERLUDE

PHILIP GLASS ON JOHN CAGE

Artists of all disciplines were affected by Cage’s ideas, either directly or indirectly. I find Glass’s interpretation to be less conceptual than most; he focuses on the interdependence of art and audience. The following is an excerpt from his autobiography, Words Without Music: A Memoir.

I had been immersed in Cage’s Silence, the Wesleyan University Press collection of writings published in 1961. This was a very important book to us in terms of the theory and aesthetic of postmodernism. Cage especially was able to develop a very clear and lucid presentation of the idea that the listener completes the work. It wasn’t just his idea: he attributed it to Marcel Duchamp, with whom he was associated. Duchamp was a bit older but he seemed to have been very close to John. They played chess together, they talked about things together, and if you think about it that way, the Dadaism of Europe took root in America through Cage. He was the one who made it understandable for people through a clear exposition of how the creative process works, vis-à-vis the audience.

Take John’s famous piece 4’33”. John, or anyone, sits at the piano for four minute[s] thirty-three seconds and during that time, whatever you hear is the piece. It could be people walking through the corridor, it could be the traffic, it could be the hum of the electricity in the building—it doesn’t matter. The idea was that John simply took this space and this prescribed period of time and by framing it, announced, “This is what you’re going to pay attention to. What you see and what you hear is the art.” When he got up, it ended.

The book Silence was in my hands not long after it came out, and I would spend time with John Rouson and Michel [Zeltzman] talking and thinking about it. As it turned out, it became a way that we could look at what Jaspers Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, or almost anybody from our generation or the generation just before us did, and we could understand it in terms of how the work existed in the world.

The important point is that a work of art has no independent existence. It has a conventional identity and a conventional reality and it comes into being through an interdependence of other events with people….

The accepted idea when I was growing up was that the late Beethoven quartets or The Art of the Fugue or any of the great masterpieces had a platonic identity—that they had an actual, independent existence. What Cage was saying is that there is no such thing as an independent existence. The music exists between you—the listener—and the object that you’re listening to. The transaction of it coming into being happens through the effort you make in the presence of that work. The cognitive activity is the content of the work. This is the root of postmodernism, really, and John was wonderful at not only articulating it, but demonstrating it in his work and his life.

From Words without Music: A Memoir by Philip Glass. Copyright © 2015 by Philip Glass, pp. 94–96. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.