Читать книгу The Grand Union - Wendy Perron - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 5

BARBARA DILLEY

With a sweet face and a beautifully unforced quality in her dancing, Barbara Dilley is a quietly magnetic force. Small in stature, her presence is contemplative yet captivating. She may begin an evening with simple walking, stretching, or spinning, with the faith that a steady motion will grow into something larger. Though she can stay with a kinetic investigation for so long that it becomes a meditation, she can just as easily glide into another person’s scenario. Her serene, velvety dancing is rooted in the downtown aesthetic of modest and minimal, but she readily crosses into more rambunctious terrain. Grounded yet somehow lofty, she can embody a range of qualities from task-like to mystical.

Barbara Dilley (born 1938) grew up in a family that moved around. Born in Chicago, she also lived in Pittsburgh; Barrington, Illinois; Darien, Connecticut; and Princeton, New Jersey. It was in this last city that she started taking ballet lessons with Audrey Estee (who also taught Douglas Dunn a few years later.) For Dilley, dance was a refuge from always being the new kid at school.1 After high school she spent a summer at Jacob’s Pillow, where she studied with Ted Shawn, Myra Kinch, Margaret Craske, and “ethnic dance” specialists Carola Goya and Matteo. She went on to Mount Holyoke, where she took Graham technique with Helen Priest Rogers, who steered her to a summer at American Dance Festival at Connecticut College. There, in 1960, she was drawn to Merce Cunningham’s work. “I liked silence, liked Merce’s physicality.”2 Decades later she said, “Nothing compares to his piercing clarity and large moving presence and to his passion for making stuff up.”3

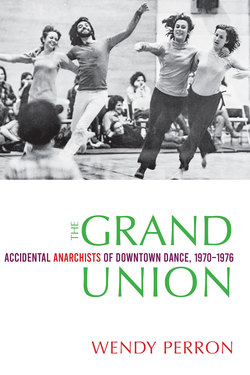

Rainforest (1968), by Merce Cunningham. From left: Cunningham, Dilley, Albert Reid. Décor of “Silver Clouds” by Andy Warhol. Photo: Oscar Bailey, courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust, all rights reserved.

After arriving in New York City that fall, she danced briefly with the Tamiris-Nagrin Dance Company.4 She studied with ballet greats Alfredo Corvino and Anatole Vilzak as well as with James Waring and Aileen Passloff.5 She savored meeting dancers “living on the other side of convention.”6

In 1961 she married Lew Lloyd, whom she had met five years earlier in New Jersey, when she was cast in a local play that he was stage managing. (Lew went on to become business manager of the Cunningham company.) Soon after giving birth to their son, Benjamin, in 1962, she joined Cunningham’s company in 1963 and continued until 1968. The first pieces she performed were Story and Field Dances, both of which made more use of indeterminacy than was usual in the Cunningham repertoire. Cunningham archivist David Vaughan surmised that this sudden (and fleeting) openness to greater choice for dancers was influenced by the young dancers of Judson Dance Theater.7

Dilley had already dipped into improvisational sessions here and there. In a studio with Forti and Brown she experienced some of Halprin’s basic structures;8 in Judson Dance Theater Concert #14, the “improvisation” concert, she danced in Deborah Hay’s piece.9 Her own choreography after leaving the Cunningham company involved improvisation, film, or props like candles.10 She also made herself available for other performances with a measure of indeterminacy. In one of Claes Oldenburg’s Ray Gun happenings (ca. 1962), she walked across a wooden plank suspended between two ladders—her pregnant belly covered in bright pink.11 In Bill Davis’s Field (1963) at Judson, she and Davis wore belts attached to transistor radios tuned to different stations.12 For Paxton’s Afternoon (A Forest Concert) (1963), she danced on moist dirt near a tree trunk wrapped in camouflage and later played in a clearing with another cast member, her two-year-old son, Benjamin Lloyd.13

But CP-AD was the first time she felt she had agency while improvising in performance. “It was beginning to seep in, the whole idea of letting each performer be able to make decisions in the performance environment.”14 She found she enjoyed this form of dance making, so she pushed for Rainer to invite more contributions from the dancers. According to Rainer, it was Dilley who kept egging her on to let the dancers have more input.15

Over time, Dilley developed an exquisite awareness of the dualities of improvisation: individual versus group, public versus private, consciousness versus subconsciousness. She felt the porousness of those binaries. In a 1975 interview she said, “[I]n improvisation you cross back and forth on that bridge between your consciousness and your unconscious energy.”16

Dilley wanted dance to be more democratic and less elitist. Part of being democratic, along the lines of the Cage/Dunn definition, was the embrace of the “ordinary.” She learned that lesson well and made the ordinary resonate:

[Y]ou take something that’s very ordinary and you distort it very slightly. Slightly through time or through absurdity or through gesture that doesn’t necessarily go with what you’re saying. And it becomes readable as a much larger thing. It starts reverberating…. You learn through experience when you are feeling a certain way which generates that possibility. That vibration…. It’s not planned or intended, but it suddenly happens. And you’re aware of it and you go with it. And you support it because its rich. It’s not only rich to do but it’s rich to be around it.”17

“To be around it” means to me that Dilley was generous with her attention. She was a good collaborator and supported her colleagues’ decisions in intelligent, fertile ways. Gordon has said that Barbara “was extraordinary at picking up on someone’s material and reinforcing it by lending her body and her mind to the action, stretching the ideas as well as following them.” In fact, her support early on helped Gordon to arrive at a turning point. Said Gordon, “I began to realize my material by watching her participation in it.”18

One of the gifts that she brought from her work with Cunningham was her sensitivity to space. “Space is this aliveness that vibrates every time the curtain goes up.” While contemplating a 1963 photo of the Cunningham company in Suite for Five, she writes, “We are alone and together in a deep full way.”19 Clearly, she felt that Grand Union continued this sensibility. She often used the term tribe to describe the group.

Barbara was highly attuned to feelings and sensations, which could perhaps be traced to being treated for polio as a child. At the age of five, she was quarantined for a month in an isolated hospital room, which her parents were not allowed to enter. She had to hold back her tears from pain and loneliness.20 As a dancer/thinker, she was psychologically probing, questioning what she wanted from performance. She wanted to be open to the imagination but didn’t want to get addicted to pleasing the audience. “In the Grand Union … we’re sort of throwing open the door to everything. Anything that occurred, I could make myself into a fool or a demon or a floozy or a queen … you had a lot of possibilities.”21

One of those possibilities was a kind of “subtlety and wanting to create an atmosphere where that subtlety can go on. And where I can then witness my own failures again.” 22 That interiority blossomed into spirituality when she followed her curiosity to Naropa University in Colorado, bringing mind and body together through the teachings of Tibetan Buddhist Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. It was at Naropa that she formulated her Contemplative Dance Practice in 1974. But one can see in the LoGiudice tapes that she is already zeroing in on contemplative actions like spinning.

For Barbara, spirituality is bound together with an almost romantic view of improvisation: “You can’t court it…. But you are, in a way, courting a lover … you’re trying to meet the unknown as a lover, in a curious way. And you’re trying to be … receptive so that whatever drops into your body at that moment, you can completely surrender to that image…. Art or any creative activity is a descending—that’s sort of spiritual perhaps—but a descending of something through you.23

Whatever is “descending” is spiritual, perhaps in its very impermanence. It descends into the body, and the body becomes a spiritual vessel. The movement descends “through” you, not to be kept by you. This is one of the unwritten foundational ideas of the Grand Union that was so well intuited by Barbara. While others may have focused on the individual freedom or the challenge to be in the moment, she spoke of GU as “teaching impermanence…. You have to take that feeling and that kind of a performance and that expectation falling to dust.”24

It was not easy for Barbara to let go of a scenario, particularly when another dancer barged in on her carefully constructed character or image. But she realized that “one must let the ego wall down to let the energy flow out into possibility.”25 Her recognition and eventual mastery of this impermanence is a gift she brought to Grand Union.

Barbara and John Cage shared an interest in Buddhism that went back to the early sixties. During the Cunningham company tours of 1963 and 1964, she had conversations with Cage on long bus rides and car rides: “John was so conversational and engaged, always. Many of his lectures as we toured were philosophical and spiritual in that open hearted, fresh way of his. As I become more immersed in the study and practice of Buddhism, I recognized how much John imparted in his lectures etc., and how it had influenced me. It was an American Dharma that he unfolded and I, too, felt that I wanted to transmit this in classes.”26

She had a deep appreciation for Cage’s philosophy of connecting art and life. When he autographed her copy of Silence, he added his definitions of the four aims of Hindu life in Sanskrit: “Artha = Goal, Kama = Pleasure, Dharma = Judgment, Moksha = Liberation.”27 Barbara treasures her connection with him, artistic and spiritual. For her, the concept of dharma art as that which springs from “the appreciation of things as they are”28 is a close cousin to John Cage and silence.