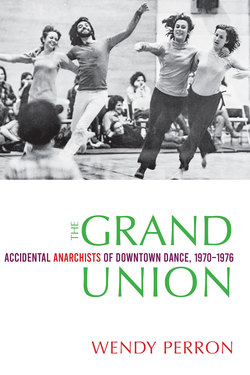

Читать книгу The Grand Union - Wendy Perron - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

HOW CONTINUOUS PROJECT—ALTERED DAILY BROKE OPEN AND MADE SPACE FOR A GRAND UNION

Ever since Judson, Rainer had been hell-bent on challenging every assumption involved in concert dance. With her emphasis on functional movement and the unadorned body (though she also deployed a wide dance vocabulary), she undermined the bedrock of professional dance: technical mastery. Taking this takedown further, with Continuous Project—Altered Daily (CP-AD) she introduced a range of modes that brought the activity of rehearsing into performance. She felt that what went on in rehearsal was as worthy of viewing as a finished piece. Therefore, in addition to performing set choreography, her score (instructions) included the following: marking the choreography (indicating it with a less-than-full-out energy), practicing the choreography, making choices about when an action would occur or whether to join in, and learning new choreography. The last of these plunged the dancers into the state of not knowing, thus robbing them of their physical assuredness. Shorn of set choreography, the performer might as well be shorn of a costume. The dancers were exposed.

For Rainer, the vulnerability of the dancer was part of her plan, part of her aesthetic. With the aid of game structures and absurdist props, she worked toward scraping away any veneer of polish. (She surely agreed with Paxton when he wrote to her in a letter that “finesse is odious.”)1 She wanted the audience to see the labor—the process—of dancing. Toward this goal, she enlisted task, play, pop culture, singular focus, multifocus, dancers bringing in their own material, choosing between options, not knowing what to expect—all of which eventually cracked open the customary director-performer hierarchy.

Rainer was asking questions: How to present two radically different ideas simultaneously? How to let the audience see the process of making? How to give performers creative agency? In addition to the experimental thrust, she valued spontaneity, so she came up with game structures designed to lift the lid on one’s natural impulsiveness.

She, along with her small crew of dancers—Becky Arnold, Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, and Steve Paxton—made CP-AD over a period of about nine months, showing it at different stages along the way. It was never meant to be a finished product, since part of the idea was to show the process of making. During this period, the performers were called either Yvonne Rainer and Group or Yvonne Rainer Dance Company.

In 1969, while in residence at American Dance Festival at Connecticut College, Rainer was experimenting with tasks and objects for CP-AD. The atmosphere during the making process was casual and workmanlike, with a ready sense of play.2 Five dancers (Steve Paxton was not able to join them) were working, lifting, hauling, trying things out. What can a body do with a cardboard box? How can a dancer be lifted the way a box is lifted? What happens if you run with a pillow and use it to cushion another dancer’s fall? What happens when all five dancers sit on the floor and try to use the group leverage to all rise together? All this experimentation fostered a sense of trust that was visible in their comfort with touch, mutual support, and difficult maneuvers.

That summer, augmenting her small group with about eighty ADF students, Rainer created a huge performance called “Connecticut Composite” that spread out over several areas of the Connecticut College gymnasium. Continuous Project—Altered Daily, a work-in-progress at the time, occupied only one area. In a second area was a studio with twenty-eight students doing Trio A, and in a third room one could watch films and hear lectures. Yet another area housed an “audience piece,” which was basically Rainer’s Chair Pillow with an empty seat to be filled by a single spectator. (Chair Pillow, which had already been part of Rainer’s Performance Demonstration at Pratt Institute in March 1969, is a spunky unison piece, setting functional actions like throwing a pillow behind oneself to the beat of Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep, Mountain High.”) Marching through the central area was a twenty-strong “people wall” that advanced and retreated inexorably, scattering audience members as it went. According to Rainer’s diagrams, this group changed configuration twenty times.3

About CP-AD that summer, dance critic Marcia B. Siegel lauded the “spontaneity, play, and variety” of the activities. She especially noticed the moment when “Rainer took a running leap and swan-dived over two big cardboard cartons into the arms of two men.” With all that was going on, including audience members sometimes joining in, she called the performance “rowdy” and said it “had the clangor and conviviality of a Horn & Hardart” (referring to the chain of working-class, cafeteria-style lunch spots in New York and Philadelphia of the thirties through the early sixties).4

Don McDonagh wrote that the overall performance, which included Twyla Tharp’s commission that summer, brought “a joyous spirit of adventure” back to the festival, which year after year had presented mostly established modern dance companies like those of Martha Graham and José Limón.5

Later in 1969, Rainer wrote letters to Paxton and Dilley, who were teaching at the University of Illinois, about the upcoming date at University of Missouri at Kansas City. She sent them her tracings of Isadora Duncan photographs with instructions to make a duet based on them. Her notes of what she expected to happen included this bullet point: “YR randomly monologuing, directing, watching, disappearing.”6 A little foreshadowing, perhaps? Her disappearing act was repeated in various forms during the next three years.7

The Kansas City performance, on November 8, 1969, turned out to be a madcap, expansive turning point. Body “adjuncts,” created by Deborah Hollingworth, included a pair of feathered wings, a foam insert that turned the wearer into a hunchback, a lion’s tail, and a humongous sombrero hat. It also provided the performers a chance to laugh at themselves or each other, deflating the self-importance of the performer.

Dilley, looking back, felt Kansas City was the beginning of the evolution toward Grand Union. Writing in the present tense, she recounted the performance in her book, This Very Moment:

Circumstances create unplanned opportunities and, that night, suddenly we make new material in front of the audience. We’ve never done this before. It is outrageous and fresh. There are moments of exquisite joy and revelation.

I write about it in a letter to Yvonne: I remember the opening bars of the Chambers Brothers “In the Midnight Hour” and doing Trio A slow, very slow, and Steve [Paxton] joining me and then fast, with and against Steve’s tempo. It was sheer delight. I felt sexy moving through material I know that slowly. I remember you… grinning at the pleasure we had. Oh, and the wings. I remember watching the pillow solo and then during Trio A the wings would sometimes flap in my face. The literary images, the dream images, the animal images… .

After the performance we stay up most of the night, sprawled across some hotel bed, talking through what happened over and over. Yvonne calls it “spontaneous behavior.” There’s no going back. We are about to become the anarchist ensemble the Grand Union, where we make up everything in front of audiences.8

Rainer, too, felt a huge release with the discovery of “behavior” as performance. In a loving, admiring letter to her dancers, she told them that because of their performance, she had an epiphany: “I got a glimpse of human behavior that my dreams for a better life are based on—real, complex, constantly in flux, rich, concrete, funny, focused, immediate, specific, intense, serious at times to the point of religiosity, light, diaphonous [sic], silly, and many leveled at any particular moment.”9 (I would say that her words mesh with my own experience of watching Grand Union.) When Rainer described the specific actions that excited her, they seem quite ordinary. (By then, with the help of past teachers Halprin and Dunn, she had mastered “ordinary.”) That was the point: what is ordinary can be art. The following is from a letter she wrote to her dancers after Kansas City:

Steve’s concentration and presence during the lifting lesson; his lying on the floor at the end; his observation of me doing the pillow-head routine. Doug sitting across the room looking at our shenanigans with a baleful eye…. David seriously working on the new stuff by himself; his interrupting me at the microphone to ask for help. As you see, I am talking mostly about behavior rather than execution of movement. It is not because I value one over the other, but because the behavior aspects of this enterprise are so new and startling and miraculous to me.10

Rainer was delighted to see good ole human behavior in an art context. It aligned with her larger project of putting life onstage, breaking the barriers between art and life.

Although the UMKC audience, having no context for Rainer’s work, could not have perceived the nature of the breakthrough, the student newspaper did report a warm response. “Not knowing what to expect,” wrote Tresa Hall, “yet not expecting what they got, the audience reacted in a very pure and delightful way.”11

After the breakthrough in Missouri, Paxton may have been the only one who saw the possibility of improvisation on the horizon. “While we were in Kansas City having a late-night talk about the performance we had just done, I said, ‘It is very obvious that we are heading for improvisation of material,’ and thereafter came a long series of responses on how impossible that was.”12

∎

As much as the “behavior” was welcome, the aspect of dance as labor was also central to CP-AD. Rainer was influenced—not for the first time—by the minimalist sculptor Robert Morris, her lover and fellow Judson choreographer. Rainer took the title Continuous Project—Altered Daily from an installation he devised at the Castelli Warehouse in Harlem and later performed at the Whitney Museum. For this “installation,” Morris went into the gallery every day and changed the arrangement of a myriad of objects.13 Rainer was impressed that he had created a fluid experience rather than a finished exhibition. (Let’s not forget that, back in the late fifties and early sixties, when Morris was married to Forti, he had tagged along to workshops given by Halprin and Robert Dunn.) Art critic Annette Michelson described how Morris’s Whitney installation involved various craftspeople and museum staff who “worked at the transport of the huge cement, wood, and steel components, converting the elevator into the giant pulley which hoisted them to the level of the exhibition floor.”14 Morris himself describes the installation as “[n]o product, just the heaving and throwing and shoving and stuffing.”15

It is this type of labor that Rainer wanted to get at. She wanted to show dancers as workers. I believe she felt this would demystify dance, move toward a more egalitarian attitude toward women, and scrape away the narcissism that she felt comes with the territory of performing.16

Continuous Project—Altered Daily (1970), Whitney Museum. With Rainer and Dunn. Photo: James Klosty.

Rainer’s love of work, especially women working together, goes back to her participation during Judson Concert #13, “A Collaborative Event in 1963,” mentioned in chapter 1. In her autobiography, she describes the teamwork necessary to accomplish Carla Blank’s piece Turnover, in which eight or nine women literally turn over Charles Ross’s huge trapezoid-like metal frame: “As half the group lifted a lower bar of the contraption from the floor, the other half reached for the top bar on the other side and in the process of bringing it to the ground raised the first four or five performers high in the air. The second group then moved to the other side to lift another part of the structure, thus lowering the dangling ones to the ground. In this fashion the whole configuration rolled crazily around the space. I found it breathtaking to engage in this heavy and slightly dangerous work with a team of women.”17

The audiences of CP-AD also had to work. In order to make sense of the radical juxtapositions (a term coined by Susan Sontag when describing happenings in 1962),18 they had to encompass two contradictory ideas at the same time (F. Scott Fitzgerald, anyone?). Rainer was fond of butting two opposite actions or moods up against each other. She wasn’t interested in snap judgments, in audiences being able to grasp an idea instantly. She wanted to engage them long enough to provoke serious thought. In a 2001 interview, when she had reentered the dance field after making independent films for twenty-five years, she was discussing the relatively new genre of video installation as performance. “I’m still interested in making things that require a certain amount of time to comprehend,” she said. “With the standard video installation, you go in, stand there for two minutes, say ‘I get it,’ and walk out. I don’t think of images in that way.”19 She preferred a complexity of images or actions, not with an obvious center or point. Like Cunningham, who scattered actions all over the stage, she liked to have several tasks going on at once. She wanted the audience to grapple with what they were seeing (the way she grappled with life), rather than to just passively receive it.

Another way that Rainer explored the complexity of images was her insight into the relationship between the body and objects. About the Whitney performance of Continuous Project (which was not only the premiere in 1970 but also its last performance before the group mutated into the Grand Union), Rainer wrote:

I love the duality of props, or objects: their usefulness and obstructiveness in relation to the human body. Also, the duality of the body: the body as a moving, thinking, decision- and action-making entity and the body as an inert entity, object-like. Active-passive, despairing-motivated, autonomous-dependent. Analogously, the object can only symbolize these polarities: it cannot be motivated, only activated. Yet oddly, the body can become object-like; the human being can be treated as an object, dealt with as an entity without feeling or desire. The body itself can be handled and manipulated as though lacking in the capacity for self-propulsion.20

The idea that a woman could be like an object in performance (not, I hasten to add, a sex object) fit nicely with Rainer’s budding feminism. It offered a solution to the “problem” of a woman’s body in performance, which was often exploited as an object of sexual pleasure for men. In the ballet world, a woman was either seducer or sylph; in modern dance, she was often either a matriarch or a woman in various states of desire. In CP-AD, a woman could either lift a box, be lifted like a box, toss a pillow, or help a mate fall or get up. So could a man. In this way, CP-AD was as ungendered as her previous works, like We Shall Run and The Mind Is a Muscle (1966). Rainer’s device of never looking at the audience in Trio A, which was initially part of Muscle, was an attempt to escape the usual tyranny of what was later called the “male gaze.” (Ironically, Rainer has often admitted that she likes being looked at as a performer.) Scholar Peggy Phelan has pointed out that “Trio A in particular anticipates” the concept of the male gaze as coined in Laura Mulvey’s landmark 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”21

The active/passive duality she set up was not keyed to gender. This concept was foundational to CP-AD and continued through Grand Union. It seems to me there were two types of passivity in CP-AD: one was for the body to assume an inanimate state, as object or sculpture, and the other was for the body to go soft, almost liquid, like water. The latter was embodied most expertly by Steve Paxton. In one section, with three limbs being pulled by Gordon, Dilley, and Douglas Dunn, he went limp, trusting them as they pulled him in different directions.22 The necessity of trust became a theme, a challenge, a shared understanding in the Grand Union, and continues to be a cornerstone of Contact Improvisation. (More about Contact Improvisation in Nancy Stark Smith’s interlude and in chapter 22.)

∎

As part of the Whitney performance of CP-AD (March 30 to April 2, 1970), Rainer arranged for several spoken recitations during the performance. She had always fed her intellectual hunger with an array of serious reading. For the Whitney, she invited prominent people in the arts to read passages she’d found about performing—written by Buster Keaton, Louise Brooks, Barbra Streisand, W. C. Fields—thereby adding another layer of inquiry into the nature of performance. Among the readers were fellow choreographer Lucinda Childs, theater director Richard Foreman, filmmaker Hollis Frampton, and art critic Annette Michelson.23 The readings at the mic, juxtaposed to the game-like physical actions, left some audience members confused, or merely unmoved. But New York Times reviewer Don McDonagh found it stimulating that “an almost contagious joyfulness” could appear side by side with a section that he considered “drained of freshness.” He felt it was all part of Rainer’s “voracious embrace of all movement full of its own weight and justification.”24

Because the task-oriented movement did not require highly trained bodies (though most of the dancers were trained professionals), McDonagh wrote, “A curious side effect of the work was the frustration of not being able to participate except vicariously in something that appeared to be fun.”25 This illusion that anyone could do it (which continued as CP-AD morphed into the Grand Union) had its roots in Halprin’s explorations in public spaces and her wish to blur the line between performer and audience, making dance more democratic.

In some ways, McDonagh (who had only the year before called Rainer’s Rose Fractions “leaden” and “stultifying”)26 represented the ideal viewer. First, because he relished the challenge of making sense of radical juxtapositions. Second, because he had enough physical responsiveness to catch the fun of it.

Another critic who enjoyed the range of moods, though she was far from effusive, was Nancy Mason of Dance Magazine: “Projecting different sides of their personalities—reserved and methodical, warm and whimsical—they use their bodies in unique ways to ventilate a primitive urge to move and express.” Mason also enjoyed Hollingworth’s bizarre “adjuncts” that were donned, at random times, by the dancers: “Barb affects an imitation lion’s tail, which bobs jauntily around as she buries her head in a pillow on the floor. David looks like a mini-Mexican beneath his giant, colorful sombrero.”27

Rainer was under no illusion that she was doing something new by allowing process into performance. Rauschenberg had created “live décor” while on tour with Cunningham; in addition to providing an assortment of found items to wear for Story, he sometimes loaned himself as part of the scenery. When the company performed Story in Devon, England, he and Alex Hay were ironing shirts upstage.28 Charles Ross had done it in the collaborative event at Judson, when he was amassing his mountain of chairs during the performance, and then again with Anna Halprin in her Apartment 6 (1965), in which he was making a paper animal—a different one each time—upstage during the performance.29 Performing process was just one device in Rainer’s arsenal in deconstructing the conventions of the theater.

∎

Rainer had a history of crossing from private to public that prepared her for the vulnerability in CP-AD. How intimate can a work of art be? She’d seen Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955) mounted on the wall. Was it a painting, a sculpture, a found object, a private corner? Mattresses, pillows—the domestic realm, the woman’s realm—were now fair game to include. She had performed in Forti’s See-Saw in 1960, which suggested a domestic relationship seeking balance. In Inner Appearances (1972, a prelude to her first film, Lives of Performers), her most private thoughts—erotic, rebellious, political, mundane—were projected onto the back wall while she was vacuuming the floor. Perhaps this short trip from private to public was best expressed in the language she used recently when referring to her decision to expose dancers to process in CP-AD: “Let it all hang out—or make new stuff right in the performance.”30

Although Rainer asked the dancers to contribute ideas, she still considered herself the choreographer. According to Paxton, it was a step-by-step process that led to the transformation of CP-AD into Grand Union. He enumerated the progressive invitation to dancers to make decisions, to bring in new material, to experiment with learning in performance. He said that “misunderstandings would continue until we had assumed more and more functions that she had under stood were her own.”31 Eventually it became clear that the logical next step in this experiment was for Rainer to relinquish control.

Continuous Project—Altered Daily (1970), Whitney Museum. With Gordon and Rainer. Photo: James Klosty.

But that was not her intention. She felt she was encouraging her dancers to experiment, not to mutiny. She wanted to give them agency as creative people instead of serving merely as “people-material.” She wanted to acknowledge the brilliance of her performers. But in a statement read aloud during the 1969 performance at Pratt Institute, she said, “The weight and ascendancy of my own authority have come to oppress me.”32 The piece at Pratt had some of the elements of CP-AD, like bringing in independent material and teaching material in front of the audience. Rainer was already questioning the director/performer hierarchy.

Even those weighty questions did not put a damper on the performance. One Pratt student, Catherine Kerr, who later became one of the longest running dancers in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, responded to the group’s exuberance: “I thought it was fabulous…. It was athletic, it was casual, it was everyday movement. I remember being totally engaged by the performance and their antics. I thought, Wow, that’s a doorway.”33

In her letters to the dancers, Rainer was exquisitely clear about what she wanted to keep control of and what she was willing to let go of. She was excited by what she was seeing: the outsize imagination and daring of her dancers, the unleashing of absurdity, and the possibility for spontaneous behavior, including rollicking laughter. In the documentary film about her, she describes her frustration: “It was like letting the horses out of the barn, but then sometimes I’d want to get the horses back in and they weren’t about to get back in.”34

Although she joked about it years later, Rainer was tormented by the uncertainties at the time:

A more serious side of the process necessarily entailed a great deal of soul-searching and agonizing on my part about control and authority. It seemed that once one allowed the spontaneous expression and responses and opinions of performers to affect one’s own creative process—in this respect the rehearsals were as crucial as the performances—then the die was cast: there was no turning back to the old hierarchy of director and directed. A moral imperative to form a more democratic social structure loomed as a logical consequence. What happened was both fascinating and painful, and not only for me, as I vacillated between opening up options and closing them down.35

Rainer’s ultimate decision to pull back from leading the group was not only a moral imperative but also a feminist moment. Feminism is about challenging ingrained hierarchies. As a choreographer, she took charge not because she wanted power but because she wanted to make work. She was a harbinger of the seventies and eighties mode of downtown dance groups wherein the choreographer asked for input from the dancers.36 She respected her dancers and perceived—accurately—that most of them were on the brink of coming into their own as dance artists. (Paxton, of course, had been her equal from as far back as the Bob Dunn classes.) According to Dilley, who credits Rainer with being the first choreographer to be interested in her as a creative artist rather than only as a performer, Rainer had demonstrated a kind of sisterly solidarity.37

If you think of supportive sisterhood as an element of feminism, if you think of equity between genders as another element, then Rainer had introduced the elements of feminism before it caught fire later in the seventies. She was generous enough to facilitate her dancers’ growth in many ways. She wanted the group to be a democracy of adults. She presented female dancers onstage as thinking, speaking, assertive women. These were some of the reasons Sally Banes called Rainer a “proto-feminist.”38

If a man were to step down under those circumstances, I think he would have closed shop completely. It seems to me that when a man has power or authority, he usually does everything he can to hold onto that power. But Rainer wasn’t interested in power. She was interested in work—and teamwork.

∎

It was only weeks after CP-AD’s official premiere at the Whitney that Rainer proposed, amid all her ambivalence, to step down as leader. She talked about it with David Gordon after a performance in Philadelphia. Gordon’s rendition of how the name of the newly configured group came about is posted on his Archiveography website. (On this site, which carries a very personal account of his career up until 2017, Gordon talks about himself in the third person.) “Yvonne don’t wanna be boss no more—she starts to say to us. No more Yvonne Rainer Dance Company—she says. David says—in Philly—after a Rodin Museum visit together—what about a new no dance company name? Like a rock band—he says. How about Grand Union? Like the super market—David says.”39

The evolution of Rainer’s group into Grand Union was confusing and disorienting. During the fall of 1970, three new people joined the group: Nancy (Green) Lewis, Lincoln Scott (aka Dong), and Trisha Brown. Apparently even the new people participated in the discussions of what the group would be. Lewis remembers those sessions: “We sat around a table in Yvonne’s loft on Greene Street discussing what and how to do things … to rehearse or not to rehearse … to stay together or not…. The others were breaking loose from Continuous Project. They were ready to simply mess around … with no one in charge. I recall it was kind of hard for Yvonne to relinquish.”40

Douglas Dunn remembers the decision to keep going: “When Yvonne absented herself [as leader], our focus was lost. We tried to rehearse. People brought in improvisational structures, but resistance was obvious. We were not enjoying ourselves. We had to decide: did we want to perform? Yes. Did we want to rehearse? No. The obvious—if outrageous—answer was staring us in the face: to walk onto the stage with no preparation. No preparation, that is, other than who we were and what we, each of us, harmoniously or not, wanted to do next.”41

Adding to the confusion was a performance at Rutgers on November 6, when Rainer’s big group piece WAR (1970) was performed concurrently with Grand Union but in a different room. This arrangement, repeated later in the month at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., reflected Rainer’s interest in what art scholar Carrie Lambert-Beatty calls her split-screen or multichannel mode. Lambert-Beatty points out that “Rainer’s aesthetic of concurrence meant that, no matter what you were watching, you were aware of what you were not seeing—of the thing coincident in time but distant in space.”42 Although confusing at the time, this “aesthetic of concurrence,” which had clearly been in operation during “Connecticut Composite,” became foundational to Grand Union.

Another incident, just a few weeks later, again blurred the line between Grand Union and Rainer’s work. In a review of Grand Union at NYU’s Loeb Student Center in December 1970, Anna Kisselgoff wrote in the New York Times that the program was performed by Rainer “and six members of her company, a group that calls itself the Grand Union.”43

Deborah Jowitt reflected the confusion of this period in her review of GU’s performance at NYU in January 1971, in which all GU members except Scott were present: “The Grand Union is Yvonne Rainer’s gang. Now officially leaderless, Becky Arnold, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, Nancy Green, Barbara Lloyd, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown tear Rainerideas [sic] to tatters, worry them, put them together cockeyed, add their own things. Rainer says, ‘It’s not my company.’ Hard to tell from her tone of voice whether she’s relieved or regretful.”44

Later that spring the confusion continued, partly because Rainer was still choreographing. When she created her India-inspired, faux-mythological Grand Union Dreams, which premiered in May 1971 at the Emanu-El Midtown YM-YWHA (now the 14th Street Y), she utilized Grand Union dancers in the choreography. By that time Trisha Brown was a member of Grand Union and did not expect to have to follow anyone’s orders. According to Pat Catterson, a dancer/choreographer who was cast as a “mortal” while Brown and other GU members were playing “gods,” Trisha’s hackles were raised, and the room was filled with tension.45

About the other attempts to share and rehearse each other’s choreography, Dilley recalls: “The outcome of it, in my memory is that nobody wanted to be anybody’s dancer. We just didn’t want to surrender any more, to anybody. It was out of that kind of irritation and frustration and bad behavior and acting out that we just said, OK next time, there are no rules, we’ll just show up and begin.”46

Gordon’s version, as told succinctly to John Rockwell at the New York Times, was this: “We were not comfortable performing each other’s work, but we were comfortable working together.”47

In pulling back from being the director, Rainer ended one thing—Yvonne Rainer and Group—but she set something else in motion: the Grand Union.

INTERLUDE

THE PEOPLE’S FLAG SHOW

In the fall of 1970, a political protest was brewing against censorship. In the art world, the spurring incident was the arrest of a gallery owner who had shown the work of artist Steven Radich, which supposedly denigrated the American flag. During the late sixties and early seventies, the flag had come to represent US military aggressions against Vietnam and Cambodia. In solidarity with the gallery owner, a coalition of arts and justice groups held meetings to decide on a public action they could take. Among them were the Art Workers Coalition, New York Art Strike, and the Guerrilla Art Action Group. They formed the Independent Artists Flag Show Committee with an eye to inclusiveness, aiming for “equal representation, women and men, of Blacks, Puerto Ricans and Whites.” The committee sent out a call for proposals for works of art that would reimagine the flag. More than 150 artists of all disciplines, including Jasper Johns, Leon Golub, and Kate Millett, responded to the call. The three organizers were Jon Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, and Jean Toche.1

Hendricks, who had been director of the Judson Gallery, knew that Reverend Howard Moody was a longtime supporter of the arts within community. When Hendricks approached Judson Church to host The People’s Flag Show, Moody was already aware of the issue. He had written a long letter of support to a Long Island woman who had been arrested for hanging a flag upside down as a protest against the Vietnam War.2 On Sunday, November 8, the day the exhibit opened, he gave a sermon defending the artists. He sent the written version to the Village Voice, which printed it. Here is the last paragraph: “The flag is a simple symbol, half a lie and half true; more of a promise than a reality. Its respect must be elicited, not commanded; the love of what it means must be given, never forced. When the flag becomes a fetish, we’re on our way to a tyranny that all patriots must resist.”3

After the Sunday service, the artists began arriving with their offerings. This was not a curated exhibit because the participating groups wanted it to be democratic and inclusive. The show officially opened at 1:00. According to Moody, Mayor John Lindsay sent staff to protect the artists.4

At 5:00, Hendricks and Toche, representing the Guerrilla Art Action Group and the Belgian Liberation Front, held a flag-burning ceremony in the Judson courtyard.5 At 6:30, Rainer and four other dancers performed Trio A with Flags, which was followed by Symposium on Repression at 7:00. Participants in the symposium included Kate Millett (representing the Women’s Liberation Movement), Leon Golub (Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam), Cliff Joseph (Black Emergency Cultural Coalition), Abbie Hoffman, Faith Ringgold, and Michelle Wallace. Other groups included the Gay Liberation Front, Women Artists in Revolution, and the Black Panther Party.

Hendricks had invited Rainer to perform for the opening—the only time-based art of the exhibit—prompting her to come up with Trio A with Flags. The dancers, in the nude except for a flag tied around the neck like a long bib, performed Trio A (which is less than five minutes long) twice through. For Rainer, “[t]o combine the flag and nudity seemed a double-barreled attack on repression and censorship.”6 The dancers who joined her, flags flowing and flapping against bare skin, were Paxton, Dilley, and Gordon from CP-AD and two of the new Grand Union people: Nancy Lewis (then Green) and Lincoln Scott. This was not a Grand Union event per se, but Rainer relied on the GU dancers, most of whom knew the long, intricate sequence of Trio A. Becky Arnold, however, refused to perform on the grounds that she was proud to be an American and “proud of the flag.”7

Feminist writer/sculptor/activist Kate Millett draped a flag over a toilet bowl (or perhaps stuffed it inside), titling the piece The American Dream Goes to Pot. This was the same year that her book Sexual Politics took the emerging feminist movement by storm, becoming a best seller.

Other offerings: Chaim Sprei assembled a flag out of soda cans. Sam Wiener made a box with mirrors that reflected rows upon rows of flag-draped coffins from Vietnam.8 Activist Abbie Hoffman came to the People’s Flag Show with the same flag shirt he wore when he was summoned to the US House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1967—for which he was arrested.9 As he spoke at the symposium, he made a point of wiping his nose on the flaggish sleeve.10

The district attorney’s office ordered the show to be closed, but the church defied the order and kept the exhibit open till the end of the week. Within two days, an unnamed person made a citizen’s arrest of Moody and Al Carmines, but then never showed up for the court dates.

The organizers of the People’s Flag Show were arrested by the district attorney’s office, charged with flag desecration, and dubbed the Judson Three.11 They were all old hands at activism. Jon Hendricks was a member of Fluxus; Faith Ringgold had previously protested the Museum of Modern Art’s exclusion of black artists; and Jean Toche was active in the Guerrilla Art Action Group, along with Hendricks. They were arraigned and released on Friday, November 13, but the legal case lingered. On February 5, the Judson Three plus Abbie Hoffman and their supporters stood on a flag to protest being shut out of a press conference in the court. On May 14, 1971, the Judson Three were found guilty. Ten days later, they were given a choice of being fined $100 or spending thirty days in jail. They paid the fine and wrote a statement saying, “We have been convicted, but in fact it is this nation and these courts who are guilty.” It went on to accuse the United States of “mutilating human beings” both in Southeast Asia and at home.12 Faith Ringgold’s poster for the People’s Flag Show, a bold design suggesting a flag on a ruby red background, was included in an exhibit at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1996, causing some controversy, and was acquired by Dartmouth’s Hood Museum of Art in 2013. “We felt in protesting a dishonorable war that we were acting as patriots,” Millett said. “And also we felt we were defending the First Amendment, which is free speech, and to us that was precious and important.”13

I have gone into some detail in order to give a sense of the political activism that Rainer and most of the Grand Union dancers felt comfortable with at the time.

∎

Trio A with Flags is an elegant version of Rainer’s signature work Trio A. Though I did not see it in 1970, I have seen it performed (and have produced it twice myself, both times at Judson Church) in various contexts over the years. When the audience is sitting on the same level as the dancers—that is, not on a proscenium stage—the potential titillation of their nudity is mitigated by the even, steady dynamic of the choreography. The ongoingness of the phrasing, the precision of the choreography, and the averted focus serve to make the dancers into a kind of sculpture, or objects, much like parts of CP-AD. Both the human body and the flag are drained of symbolism. Gender differences, so obvious in the nude, diminish in importance because the women and men are doing the same movement with no gender affect. The dance is so calm and uninflected that the audience is free to focus either on how the specific movements—loping, tapping the foot, thrusting hips sideways, somersaulting—affect the flag, or on what it means for an American flag to grace or graze the body as it moves through odd coordinations.14

Trio A with Flags, by Yvonne Rainer. Foreground: Lewis. Screen grab from film of The People’s Flag Show, Judson Memorial Church, 1970. Courtesy Special Collections, New York University.

Watching the archival film, one can feel that the five dancers are all swimming in the same stream, even though this was not officially a GU event. Of course, in later performances they would all be swimming in different directions—in pairs, groups, or alone. But it is also possible to glean from this film a kind of loose aesthetic container, an awareness of the breath and rhythms of their coworkers.