Читать книгу The Grand Union - Wendy Perron - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

A SHARED SENSIBILITY

All the Grand Union members had their own brand of charisma, each vivid in her or his own way. The downtown audience flocked to see them because we felt we knew them. Even their management agent, Mimi Johnson of Performing Artservices, called the group “personality driven.”1 If the term personality can be stretched to include compositional flair, responsiveness to others, and the powers of spontaneous decision making, I suppose that is true. But Grand Union members also had something in common, a shared ethos. So I decided to use this chapter to describe those commonalities and then, starting in the next chapter, branch out to their singularities.

They all had a downtown understatedness, a relaxed “everyday body,” to quote Jowitt,2 accented by a Zen-like readiness to pounce. This demeanor, this sly facade of “ordinary” (aka deadpan, which I get to later) had everything to do with the Cage/Cunningham milieu they were all steeped in. Dilley, Paxton, Douglas Dunn, and Valda Setterfield (Gordon’s wife and muse, who guested with Grand Union in the 1976 series at La MaMa) had danced in the Cunningham company, and Lewis, Brown, and Rainer had studied with him.

Cunningham had already pried dance away from narrative, creating a new freedom in movement exploration. What Grand Union members understood was that this freedom didn’t mean a free-for-all. It wasn’t supposed to be like kids just let out of school. Paxton had observed that whenever Cage directed musicians unfamiliar with his work, the composer would sometimes have to explain that “freedom was to be used with dignity.”3

Cunningham deployed chance operations specifically to divert possibilities away from personal taste. For instance, while working on Summerspace (1958), he applied a chance procedure—probably tossing coins or throwing dice—to eight elements in each dancer’s track, including direction, speed, level, duration, and shape. In doing so, he created physically challenging choreography involving many difficult jumps and turns, sudden falls, and abrupt changes of direction and speed.4

Merce Cunningham and John Cage, Westbeth Studio, 1972. Photo: James Klosty.

But there was a more spontaneous way that Cunningham embraced chance, and I saw it once onstage. I think it was at New York City Center, probably in the seventies. While Cunningham was dancing a solo, a baby in the audience let out a howl. An amused grin flitted across his face. He was “in the moment,” easily absorbing the world around him—rather than shutting it out, as some performers do. That kind of chance element is what the Grand Union thrived on: being open enough to respond to an unexpected event.

Another common ability is that they could all dance in silence. They didn’t need music in order to dance. In fact, much of their own work during that period was done in silence—or to sounds rather than music (although John Cage would not make that distinction). They considered music that “matched’ the dance to be old school. Rainer even wrote a screed against music as part of a performance text in which she called herself an “unabashed music hater.” Although she invented playful spellings like muzak and moossick in her hilarious diatribe, her main point was that dance should stand on its own.5 Paxton made a dance in which he used an industrial vacuum cleaner to pump up a room-sized plastic bag and then emptied the air out, intending to record the noise for use in his nearly nude duet with Rainer, Word Words (1963). (The recording never did get used for its intended purpose.) Trisha Brown, too, was happy to make dances in silence in the early days—or sometimes to a tape of Forti making sounds, as in Trillium (1962), Lightfall (1963), and Planes (1968). When I was on tour with Trisha in the seventies and we gave lecture-demonstrations, someone would ask, “Why don’t your dances have music?” She would counter with, “Do you need music when you are looking at sculpture in a gallery?”

This attitude toward music was of course influenced by Cage and Cunningham, who famously separated dance and music in the working process. It was left for each individual viewer to make aesthetic sense of their convergence. This is related to the Dadaist idea that the eye/ear/mind will create its own cohesion when faced with radically different elements. The Cage/Cunningham mode influenced Grand Union’s method of choosing music, which was … haphazard. The dancers would bring in records to put on the record player; on tour, they would shop at a local store, buy a pile of records, and give them to the stage crew.6 Then they might, during the performance, say to a stagehand, “Let’s have music here,” or motion to a crew member to put a record on, or, trusting even more to chance, allow the crew to choose which record to play when. Because Paxton, Dilley, and Douglas Dunn had all danced with Cunningham, they were familiar with the state of not knowing the music until the moment of performance.

Cunningham revolutionized choreographic use of space as well as of sound. He decentered the stage in much the same way that Jackson Pollock decentered the canvas, so the center of the space was no longer the most compelling spot. As mentioned in chapter 1, Cunningham had proposed in his 1957 lecture on Halprin’s deck that the entire performance space could be activated. The audience had to choose where to focus in this new “allover” space (to use a term often applied to Pollock). Another point Cunningham made in that lecture is that it was not necessary to have a single front.7 In many Grand Union performances, the audience sat in an arc, a circle, or a square surrounding the dancers. These two issues contributed to the democratization of the space, which could affect the way the audience experienced the performance. Barbara Dilley, while watching the archival tapes of the LoGiudice Gallery performances (in which the audience sat on three sides), noticed, “One person looks right, the person beside her is gazing left. There’s no proscenium focus here, but rather a three-ring circus.”8

From Cunningham, they also learned to have a steadiness in phrasing. None of the dramatic Martha Graham–type dynamics or the noble arcs of Doris Humphrey for them. (Trisha once said to me, “I don’t know why Martha Graham shoots her wad on every movement.” She was talking about the lack of subtlety, the predictability, and what she perceived as false urgency.) Cunningham’s sense of timing had an Eastern tinge to it; his phrasing seemed to be ongoing rather than building toward a climax. That ongoingness could have been influenced by Cage’s interest in Zen. But it also reflected Cunningham’s locating the choreographic impetus in “the appetite for dancing” rather than the desire to tell stories.9

Related to this aesthetic was the deadpan, or what Sally Sommer called the “calm face,”10 which was natural to all GU members. Give nothing away, dramatize nothing. This relaxed expression goes back to Judson Dance Theater. As Paxton wrote when looking back, “there seemed to be some unspoken performance attitude at Judson which called for a deadpan façade.” He felt they were searching for a new performance demeanor to match the new choreographic approach in which performers could make choices, and that the solution was to be absorbed in the process. “So we tended to inhabit movement,” he concluded, “but not animate it.”11

∎

The classic deadpan can be construed as being influenced by an African American aesthetic. Dancer/scholar Brenda Dixon Gottschild calls this kind of facial composure “the mask of the cool.”12 In her landmark book, Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance, she enumerates the ways that black culture has affected contemporary dance and performance. She doesn’t deny the influences of Dada and Bauhaus from Europe, or Zen and martial arts from Asia, but she contends that the Africanist influence (meaning African American as well as African diasporan) has been overlooked. When she focuses on postmodern dance, she claims that “the Africanist presence in postmodernism is a subliminal but driving force.”13 To be specific, she writes, “The coolness, relaxation, looseness, and laid-back energy; the radical juxtaposition of ostensibly contrary elements; the irony and double entendre of verbal and physical gesture; the dialogic relationship between performer and audience—all are integral elements in Africanist arts and lifestyle that are woven into the fabric of our society.”14 Dixon Gottschild identifies Rainer, Gordon, Brown, Dunn, and Paxton as having absorbed some of these qualities.15 She points out that Contact Improvisation, which emerged from Grand Union, adopted the lingo of black jazz, using the term jam for their sessions. When Dixon Gottschild identifies a “cool, mellow state that can be termed ‘flow,’” it sounds like a pretty good description of Grand Union’s aesthetic. The word “cool” can be used by many people to express many qualities, but I think the following spontaneous remark, taken broadly, could be said to support Dixon Gottschild’s point of view: When I gave a presentation on Grand Union showing archival videos at the Seattle Festival of Dance Improvisation in 2018, one woman in the audience blurted out, “Did they know how cool they were?”

Of course all artists draw from a variety of sources. The attraction of white artists during that period to black culture is nicely described by producer/curator Robyn Brentano: “The white avant-garde’s interest in and appreciation of African-American dance, music, visual art, and literary idioms, style, and values was motivated by a complex mixture of genuine respect for and appreciation of African-American artistic achievements, a romanticization of blacks that reinforced certain racial stereotypes, and a sense of a shared antibourgeois stance.”16 I think this stew of responses reflects both conscious and unconscious attitudes.

∎

Some of the GU dancers, like many in the Cunningham/Cage milieu, were on the rebound from Martha Graham’s dominating aesthetic. No one discredited Graham as the pioneering American artist who brought modernism to dance. But these young dancers wanted to go their own way. As mentioned, Halprin had done battle with the Graham theatricality in the mid-fifties. Not much later, Rainer also came up against the Graham aesthetic. At first she was overwhelmed by this icon’s artistic and psychological force but later came to prefer Cun ningham’s subtler style, or what she called his “implicit humanity.”17 The aversion to Graham’s style for those who favored Cunningham at the time was perhaps best expressed by Carolyn Brown. She wrote that the classes at the Graham school “seemed to demand a kind of emotional hype that felt dishonest, extraneous, external, and artificial—unrelated to my understanding of Dance (with a capital ‘D’).”18

Some had also done battle with Louis Horst, Graham’s mentor, music director, and one-time lover. He had been determined to give shape to the new twentieth-century dance by teaching musical forms as choreographic forms. Horst tried (some say heroically) to steer modern dance away from the ballet lexicon as well as from the too-vague “interpretive” dance.19 But Horst himself became quite rigid in his teaching. He insisted on the A-B-A format and other musical structures to preserve theatrical cohesiveness. He treated up-and-comers like Trisha Brown and David Gordon with disdain. In a 1973 feature article in Dance Magazine, Robb Baker asked both Gordon and Brown about their experiences with Horst at American Dance Festival, which was hosted by Connecticut College during the fifties and sixties. “He made us work in prescribed forms,” Gordon complained. Gordon didn’t exactly rebel, but he interpreted the definition of a duet with such wide latitude that Horst never called on him again.20 Brown said he was “unforgiving” about her process and was clearly dismissive of improvisation.21 When it came time for Horst and a panel of ADF instructors to decide if her solo Trillium (1962) was to be included in the final concert, they voted No. (In fact, the students protested the panel’s decision and created quite a stir that summer of 1962.)22 She felt that Horst relied too heavily on musical forms in his assignments. Bob Dunn’s class, on the other hand, embraced a plurality of methods, emphasizing process over product—a very sixties philosophy. His approach was both a relief and a stimulation for Gordon and Brown.

∎

Dilley had this to say about the Grand Union performers’ familiarity with each other as an ensemble:

We had some kind of subterranean associations that we all shared, either from our past history with one another or the fact that we were all living in SoHo at the same time. We shared a kind of collective unconscious … a mutual vocabulary—psychic vocabulary, physical vocabulary, performative vocabulary, intellectual vocabulary. We were in and out of one another’s worlds for many years—not only in the Grand Union but we were in each other’s performances, Cunningham and Cage, and then there was Judson. Some people had stronger roots in Judson than I did. But we shared this atmosphere, this collective environment…. It was, for me, a big part of how I navigated everything.23

One of the hallmarks of this shared vocabulary was patience, a restraint that balanced out the moments of wild abandon. In the 1975 Guthrie performance at Walker Art Center, Brown began the evening by treading softly and slowly around the edge of the space. Eventually Gordon joined in, mirroring her exact angles as she shifted her weight, barely traveling. She kept her arms folded above the waist, and his hands were stuffed in his pockets. But the body angles were absolutely parallel. For almost twenty minutes this doubling was the main thing happening. Then Dilley joined Brown and Gordon, also mirroring the slow-change angles, but with her hands clasped behind her. Gradually the three started reaching out and making contact, but before that it was like a walking meditation with a steadily shifting sense of direction. The moment they collided with Paxton laying down a swath of silk, the performance took off. But that encounter wouldn’t have had an impact if the long period of restraint hadn’t preceded it.

∎

A pacifist air pervaded Grand Union’s concerts. The nonviolent, antiwar protests set the tone of the day, and the dancers were involved in some of those actions. Dilley joined the rough-hewn, peace-loving Bread and Puppet Theater for one of the protest marches down Fifth Avenue.24 Rainer, along with Douglas Dunn and Sara Rudner, led a solemn peace march through the streets of SoHo to protest the invasion of Cambodia.25 An Eastern influence, too, wafted in from yoga, meditation, and martial arts forms like tai chi and aikido. When compared with the current craze for aggressiveness in dance performances, Grand Union seems an oasis of calm. The group had plenty of edginess, but they expressed it without resorting to any kind of physical violence.

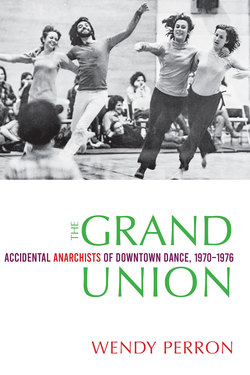

GU at 112 Greene Street, 1972. From left: Paxton, Lewis, Rainer, Gordon. Photo: Babette Mangolte.

∎

Downtown dancers were becoming very involved in body awareness. Performing in lofts and churches, they were focusing on the space in front of them, not “projecting” to the balconies. Those “everyday bodies” were consciously relaxed; they could let go of the strenuousness that is built into dance training. The label “somatic practice” came later, but at the time Elaine Summers, who had been one of the first interdisciplinary artists at Judson, was developing “kinetic awareness.” This technique, also known as the “great ball work,” uses different sized rubber balls to release unnecessary tension. Influenced by pioneering somatic practitioners like Charlotte Selver, Carola Speads, and Mabel Elsworth Todd, she was able to slow down and become conscious of muscle usage to avoid pain. Summers attributes some of the development of kinetic awareness to the Judson aesthetic of more relaxed everyday movement.26 It was a mutual exchange: both Brown and Gordon (and later, Douglas Dunn as well) studied with Summers. Rainer and Lewis studied briefly with June Ekman, who, after spending years in the late fifties on Halprin’s deck, immersed herself in Alexander technique, which repatterns movement habits to promote ease of motion. (Halprin is an acknowledged pioneer of somatic practice, starting in the sixties.) Paxton was a serious student of aikido, a form of Asian martial art that teaches how to soften the body while tumbling or responding to aggression.

Banes points out that the dancers’ brand of somatic practice was part of a larger zeitgeist of body consciousness of the period, partly fueled by Zen studies and psychedelic drugs. Body/mind therapies like Gestalt, Rolfing, Reichian therapy, and encounter groups that were popular at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California (where Halprin had given workshops), infiltrated the mainstream. “[T]he bodies created by the early sixties avant-garde included a conscious body that imbued corporeal experience with metaphysical significance, uniting head and body, mind and gut.”27

∎

Without any lessons in theater improvisation, all Grand Union members instinctively understood the edict of comedy improv to say “Yes, and.” Whatever was presented by one’s fellow performers, you accept it and take it from there. They each had the physical and emotional flexibility to veer off into a fellow improviser’s gambit and leave their own exploration behind. Dilley called it “opening up your receptors.”28 This relates to the communal sense I spoke of earlier, the willingness to swim in the same waters as another dancer. The GU members’ sense of community meant unwavering support for each other in performance. They each could be leader or follower, active or passive, foreground or background. As Paxton has written, “[F]ollowing or allowing oneself to lead is each member’s continual responsibility.”29

I mentioned radical juxtaposition earlier as a method of Rainer’s while making Continuous Project—Altered Daily. This possibility of coexisting opposites was part of the awareness of all the GU dancers. Two people can be involved in a tender, slow-motion duet while a third is yelling like a truck driver. The two modes seem at first to have nothing to do with each other. But maybe they do, or maybe they could. According to the Dadaist concept, each viewer makes sense of the collision in her or his own way.

INTERLUDE

RICHARD NONAS’S MEMORY

Richard Nonas, an internationally known sculptor, was part of 112 Greene Street and also assisted Trisha Brown in both Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970) and Walking on the Walls (1971). When I emailed him about this book, he immediately sent the following message:

I loved the Grand Union. Loved their wild and only semi-controlled interactions because I already knew their own individual work. Loved, I mean, the way they stroked and challenged each other. Loved the constant pushing and pulling and teasing while being themselves both pushed and pulled and teased; and acknowledged. Loved the way they trusted and tested each other. The way they surprised each other. And then laughed. They (and we watching) were puppies tumbling, sliding and sometimes hiding in a pet-store window—but the youngest and most curious puppies I could imagine, investigating our own shared world. What a show it was—and what a world.1