Читать книгу Dutch Treats - William Woys Weaver - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

DUTCH TREATS:

Cuisine as Living Tradition

Pennsylvania is one of the few places in the United States where rich folk tradition and the culinary arts meld seamlessly to create a magical yet down-to-earth regional cookery, unlike any other in the Old World or New. Pennsylvania Dutch cookery – the real thing, not the pallid tourist knock-off – remains a buried treasure in America’s own backyard: not yet trendy, but moving in that direction. The 25 counties that represent the broadest extent of the Pennsylvania Dutch Country form a Switzerland-size heartland of culinary tradition based on local produce, wild-foraged ingredients, and a respect for the living soil inherited from Old World farming customs. The iconic stone farmhouses of rural Pennsylvania have become lasting metaphors for all that is American in the best sense of cultural fusion and a food culture derived directly from the landscape that nurtures it.

The term Pennsylvania Dutch applies to all the many immigrant groups who came to this region from different parts of Germany and Switzerland. Many people mistakenly believe that Pennsylvania Dutch means Amish: it does not – the Amish represent about five percent of the total Pennsylvania Dutch population. The use of “Dutch” by colonial officials is an old English vernacular, which applied to anyone from the Rhine Valley: Low Dutch from Holland, High Dutch from Switzerland. Even William Shakespeare used this term, and not surprising, this is also the label the Dutch prefer themselves and for their language since their culture is no longer German. It quickly evolved into an American identity of its own, as the recipes in this book should demonstrate.

Calendula – the official flower of the Pennsylvania Dutch

While fieldwork has identified more than 1600 unique dishes not found in cookbooks or restaurants, I have culled from that list what I feel are the best from our baking tradition. This is the first book to explore traditional Pennsylvania Dutch baking, with about 100 representative recipes (I say “about 100” because some recipes contain other recipes within them so it’s all in how one counts). Most of these recipes have never before been published. Indeed, most of them have been acquired only through fieldwork interviews and come with back-stories – and often with folk tales as fresh and compelling as anything collected in the 1800s by the Brothers Grimm.

Our food traditions have their own saints and sinners, their own stories, and a cast of characters as colorful as the lush, bountiful landscape that has produced them. Where else in America will you find the Waldmops? He is considered “lord of the beasts,” a father figure to all the forest creatures as well as king of the wee folk who protect our gardens and fields. Our Waldmops rules over fields and gardens and the “colors” of the four winds that define the year’s growing seasons. The moon may instruct us when to plant, but it is the green wind from the southeast that bears the warm spring rains required for a garden over-plus and the harvest bounty that makes the recipes in this book possible.

You may spot our Waldmops cookie lurking along the margins of several pictures in this book. According to folklore, he wears a coat woven of willow leaves, spleenwort, and moss and dons a magical top hat fashioned from ivy, wintergreen and yew twigs – or from mistletoe when he can find it. Waldmops has a daughter called Ringelros (wreath rose) who is none other than the sunny calendula, the official flower of the Pennsylvania Dutch. She inhabits kitchen gardens to protect them and the farmhouse from plagues and pestilence, and thus figures in many recipes of a curative nature.

The Waldmops can also claim a bad-tempered brother known as the Bucklich Mennli (little humpback man) who inhabits dark places in houses and barns. He is the bane of the Pennsylvania Dutch kitchen due to his pranks: ruining cakes, upsetting rising bread or stealing cookies hot from the oven. The old custom was to appease him by setting out a saucer of cream and a piece of cake on the hearth to keep him from meddling in household affairs. If he rose too far out of line, it was always possible to invoke St. Gertrude to send in her cats, since the little humpback man was terrified they would eat him – and they probably would.

St. Gertrude was the patron saint of kitchen gardens and cats. Her official day was observed throughout the Dutch Country on March 17, the traditional start of spring planting for the Pennsylvania Dutch. Gertrude’s Datsch (a type of hearth bread, page 103) was scattered in the four corners of kitchen gardens to insure that the wee folk who lived there would continue to guard and protect it for the benefit of the household that oversaw its planting. Gertrude and Ringelros worked together to make certain that the bees found their nectar and that coriander yielded enough seed for Christmas baking, and caraway for cakes and pretzels.

These characters, mythical or real depending on your closeness to Nature, stand behind the stories for many of the recipes in this book. They give our remarkable cuisine its meaning and connectedness to who we are as Pennsylvania Dutch and to our place in the Green World around us.

So it should come as no surprise that with so many spirits in the wheat and Ancient Goodness in the land, we have made a special effort in this cookbook to invoke only the best ingredients, Pennsylvania grown, since they represent our cultural authenticity as we know it – and perhaps are one reason many Pennsylvania Dutch are known to attain such a great and fruitful age. Thus, in every recipe we have used wherever possible locally raised, harvested and milled non-GMO organic flours and other local ingredients. Pennsylvania is the third most important agricultural state in the country, and the leading source of fresh produce on the East Coast. We represent a special niche in American cuisine. It may be no exaggeration to suggest that American Cookery was invented here (a tale of culinary fusionism that I intend to take up in a future book on Philadelphia cuisine).

For those unfamiliar with this aspect of American history, the fusion of different early immigrant cultures first arose in colonial Pennsylvania, a region where free-minded Quakers encouraged different peoples and religions to settle side by side, to intermarry and share the bounties of the Peaceable Kingdom together. While the Pennsylvania Dutch managed to retain their own distinctive identity, their culinary traditions were quickly Americanized, and that is why the recipes in this book represent a New World culinary tradition unique among all other American regional cookeries.

The roots of Pennsylvania Dutch cookery trace to Southwest Germany and Alsace in such foods as New Year’s Pretzels, Lebkuchen, or Adam and Eve Cookies. But through the blending of Old World regionalisms and New World realities an entirely new culinary expression was born. Old Germany knows nothing of Fish Pie or Whoopie Cakes, Chinquapin Jumbles, Boskie Boys or Peanut Datsch. The inventiveness of the Pennsylvania Dutch housewife has taken these heirloom baking traditions into areas unknown to their Old World ancestors. The end result is cookery as thoroughly American as Shoofly Pie.

From a technical standpoint, Pennsylvania Dutch baking is highly developed and based on the idea of interchangeable parts. This harks back to the innate frugality of the Dutch themselves, who waste nothing and find creative ways to repurpose leftover food. Thus, dough for one type of bread can be reinvented with additional ingredients to make something else. Crumbs from cakes can be used to dust bread or cake pans, crackers are turned into pie, pie crusts can be transformed into cookies or into the ever-pragmatic Slop Tarts that Dutch children find in their school lunch boxes.

Since there are many technical dialect terms in Pennsylvania Dutch cookery, I have included a glossary (page 163) illustrated with pictures of traditional baking tools and ingredients. You do not need to own these utensils to bake the Dutch way, but it helps to know what they look like so that you can find substitutes if you want them.

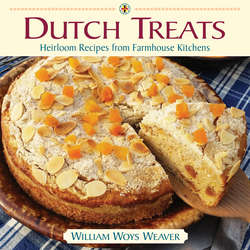

About the photography: Pennsylvania Dutch food, especially farmhouse cookery, has an appearance that is unique; it looks best straight from the oven in settings that represent the spirit of its long tradition. With that in mind – and with an eye long trained in the cuisine and the tonalities of the ever-changing seasons – I photographed many of the recipes at the historic Sharadin Farmstead, home of the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University.

Pennsylvania Dutch cookery, whether savory meals or festive baking, is highly seasonal and pegged inevitably to the phases of the moon, as outlined in our old-time almanacs. These traditions are probably best expressed in the folk tales about our Waldmops, who represents the Earth in all its diversity and fertility. By leaving Antler Cookies for him in the woods each Fastnacht (Fat Tuesday), we remind him of our respect for the Green World around us and that we are friends and allies in making this land a better place.

While the Waldmops was certainly no baker, his protective supervision over the grains that produced the flours used in our baking tradition was considered vital to the outcome of every baking day. The so-called “spirits in the wheat” connected his natural world with that of the table.

The spirituality of Pennsylvania Dutch food, whether folk belief or religious, is doubtless best expressed by our bread, which is the subject of the first chapter.

Saffron Bread